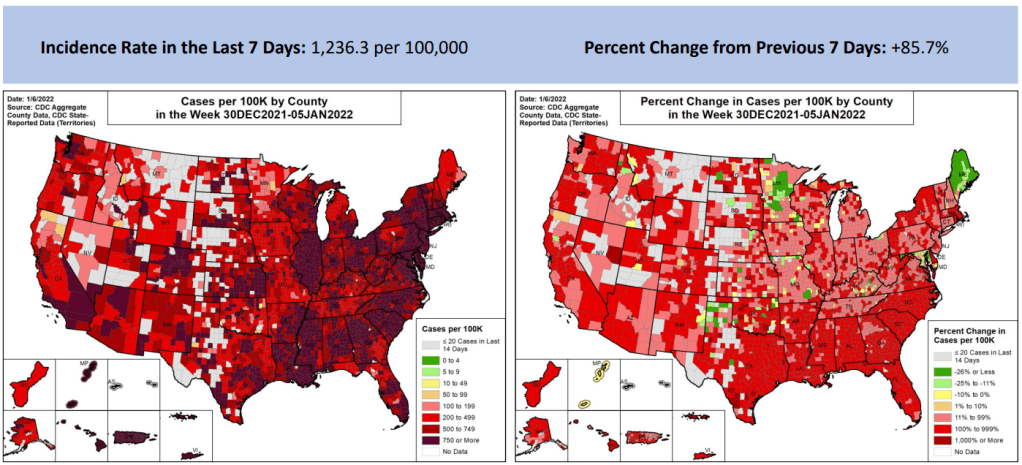

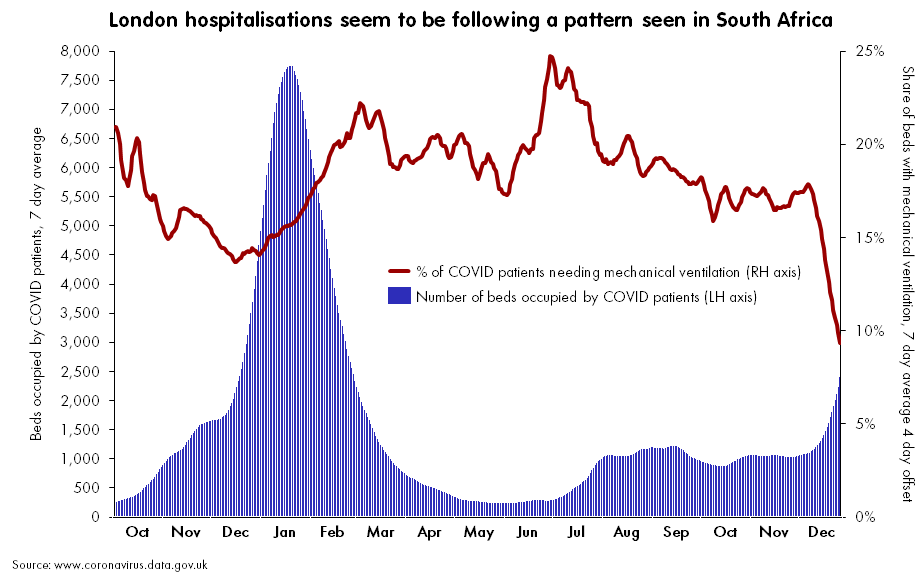

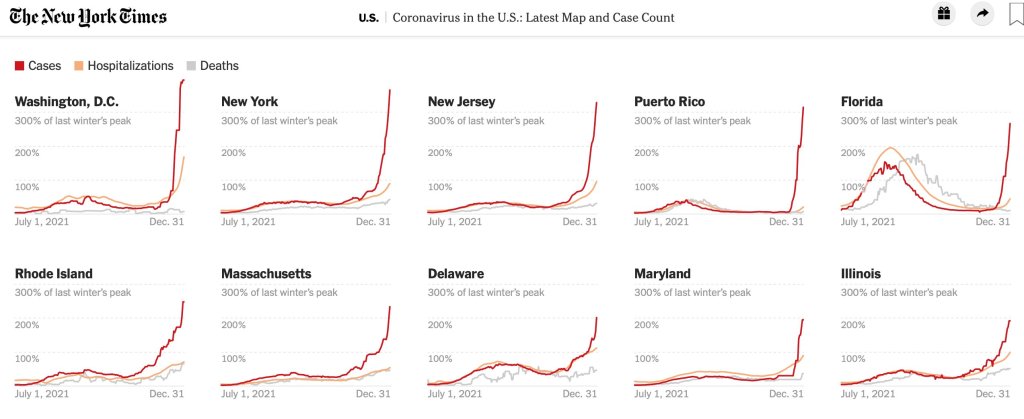

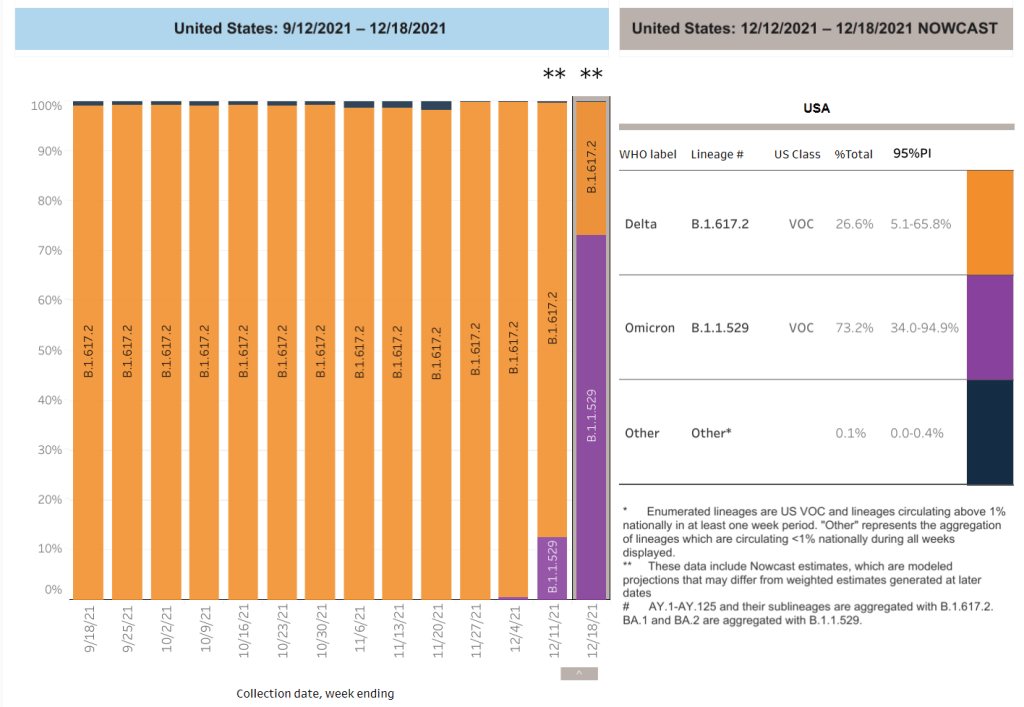

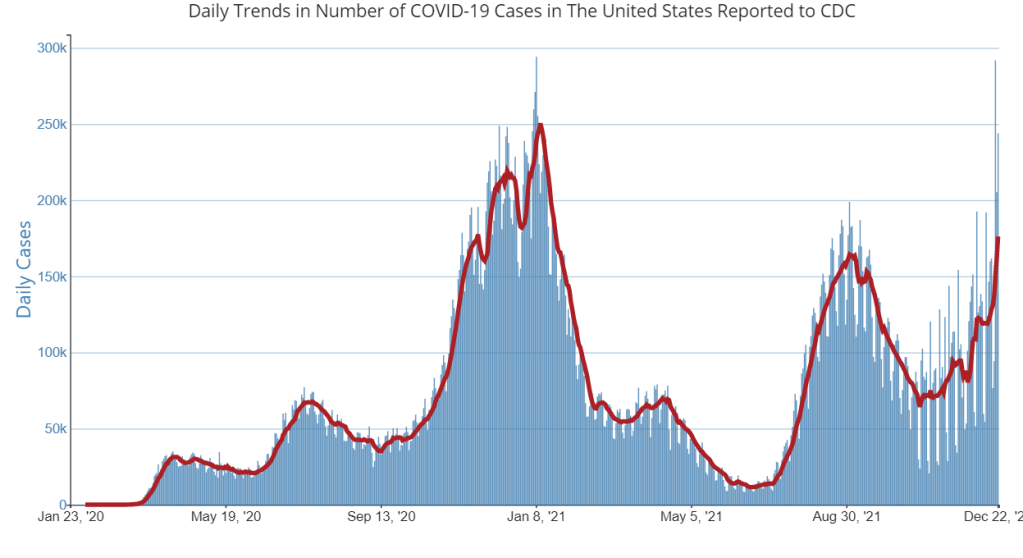

As Omicron spreads rapidly through the U.S., this variant is driving record case numbers—and record demand for testing, including both PCR and rapid at-home tests. In other words, it feels harder than ever to get tested for COVID-19, largely because more people currently need a test due to recent exposure to the virus than at any other time during the pandemic.

Also this week, the CDC changed its guidance for people infected with the coronavirus: rather than isolating for 10 days after a positive test, Americans are now advised to isolate for only five days, if they are asymptomatic. Then, for the following five days, people should wear a mask in all public settings. This guidance change has prompted further discussion (and general confusion) about who needs to get tested for COVID-19, when, and how.

Here’s a brief FAQ, to help navigate this complicated testing-and-isolation landscape. In addition to the CDC guidance, it’s inspired by a recent question from a reader about testing and isolation following a positive PCR result in her family.

What’s the difference between being infected and being contagious?

As we think about interpreting COVID-19 test results in the Omicron era, it’s key to distinguish between being infected with the coronavirus and being actively contagious.

- Infected: The virus is present in your body.

- Contagious: The virus is present in your body at high enough levels that you can potentially spread it to other people.

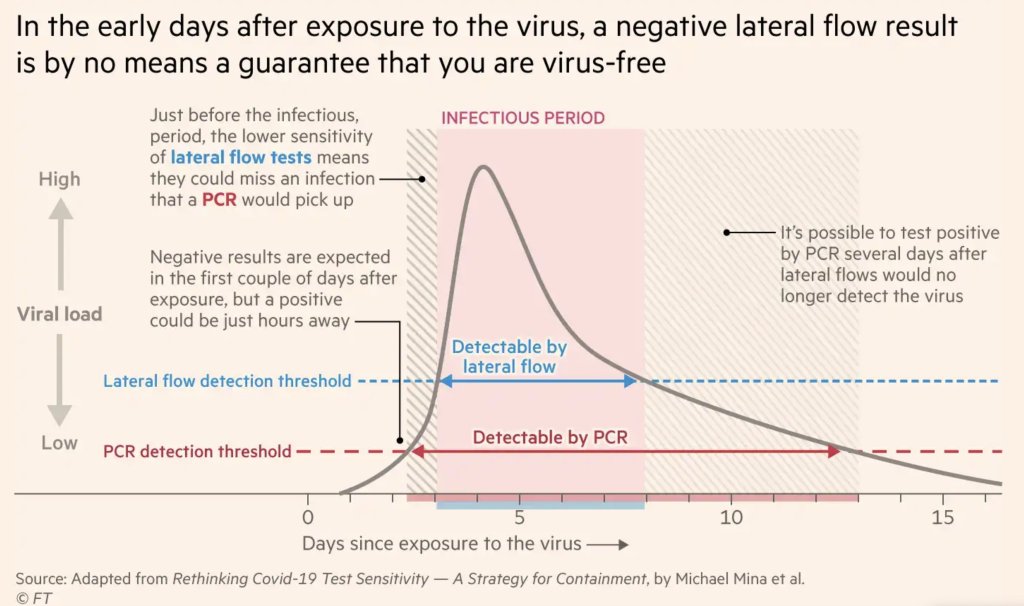

In a typical coronavirus infection, it takes a couple of days after you encounter the virus—i.e. breathe the same air as someone who was contagious—for the coronavirus to build up enough presence in your body that tests can begin detecting it. PCR tests can typically detect the virus within one to three days after an infection begins, while rapid tests may take longer.

How do you use testing to tell if you’re infected and/or contagious?

Timing is extremely important with coronavirus tests, and has become even more so with Omicron. If you learn about a recent exposure to the virus, you don’t want to get tested immediately after that exposure, since the test would not pick up a potential infection yet. Say you had dinner with a friend on Wednesday, and they tell you on Thursday that they just tested positive; you should wait until Friday or Saturday to get tested with PCR, or until Saturday or Sunday to get tested with a rapid at-home test. (And ideally, you would avoid interacting with other people while you wait to get tested.)

PCR tests can detect the virus within a couple of days of infection. Rapid tests, which are less precise, generally can’t detect the virus until it’s at high enough levels for someone to be contagious. This can take time—though Omicron may have shortened the window between infection and becoming contagious to just three days, according to some early studies. A new CDC study released this week provides additional evidence here.

This chart, an adaptation of a figure by rapid test expert Michael Mina published in the Financial Times, shows how someone could potentially test negative on rapid tests for multiple days after a coronavirus exposure, even though they are infected:

When this person tests positive on a rapid test, the result indicates that they’ve become contagious with the virus. Then, it’s possible that the person may continue testing positive on PCR tests after they stop testing positive with antigen tests, because they are no longer contagious but continue to carry enough virus genetic material that a PCR test can pick it up.

How do you get ahold of rapid tests, in the first place?

In order to use rapid tests to tell whether you’re contagious with the coronavirus, you need to get some rapid tests! Here are a couple of suggestions:

- Order online from Walmart: If you look at this website right now, Walmart will probably say that Abbott BinaxNOW rapid tests are out of stock. But if you leave the page open and refresh often, you may be able to snag some rapid tests right after Walmart restocks (which happens roughly once a day, I think). I like ordering from Walmart because they’re cheaper than other BinaxNOW vendors and ship quickly, usually within a week.

- Order online from iHealth Labs: iHealth Labs is one rapid test manufacturer that’s grown in popularity recently, as an alternative to BinaxNOW. You can order up to 10 packs (with two tests each) directly from the manufacturer, and report test results in an app. In my experience, though, iHealth Labs is slower to ship than other distributors; an order I placed on December 22 is due to arrive two weeks later, on January 5.

- Use NowInStock to see availability: This website tracks rapid test availability at a number of websites, including CVS, Walgreens, Walmart, Amazon, and others. It’s helpful to see your options for a number of different tests, but bear in mind that tests sold by third-party vendors (like Amazon) may be less reliable than those sold directly by pharmacies.

- Follow local news: A lot of city and state governments have recently started making rapid tests available to the public for free, from D.C. libraries to Connecticut towns. I recommend keeping an eye on local news and government websites in your area to look for similar initiatives—or, if your area isn’t making rapid tests available, call your local representative and ask that they do!

Why did the CDC change its guidance for isolation?

As I mentioned above, the CDC recently changed its guidance for people who test positive for the coronavirus. If someone has no symptoms five days after their positive test result, they can stop isolating from others—but they need to wear a mask in all public settings.

According to the CDC, the new guidance is “motivated by science demonstrating that the majority of SARS-CoV-2 transmission occurs early in the course of illness, generally in the 1-2 days prior to onset of symptoms and the 2-3 days after.” In other words, the CDC is saying that people are generally contagious for a few days after their symptoms start. After that, they’re less likely to infect others, so isolation may be less necessary—and good mask-wearing may be sufficient to prevent further coronavirus spread.

Many experts are attributing the guidance chance to economic needs: as Omicron causes flight cancellations, closed restaurants, and other business disruptions, a shorter isolation period can help people get back to work more quickly. The recent isolation change follows a similar guidance change the previous week, which said healthcare workers could shorten their isolation periods if their facilities were experiencing staffing shortages.

What are experts saying about the new guidance?

Much of the commentary is not positive. While the CDC said the new guidance is “motivated by science,” the agency has failed to cite specific studies backing it up—though some such studies exist, as Dr. Katelyn Jetelina discusses in this Your Local Epidemiologist post.

Generally, it does seem that most people—particularly vaccinated people—are no longer contagious five days after their symptoms start. (Reminder: five days after symptoms start could be seven to nine days into the infection period, since it takes time for the virus to build up in your body and cause symptoms.) But this is by no means guaranteed for everyone, as each person infected with the coronavirus has a unique COVID-19 experience.

As a result, many experts have said that the CDC should have required negative rapid tests for people to leave isolation after five days. A negative rapid test would indicate that someone is no longer contagious, the argument goes, and they can then go back into the world. In the U.K., two negative rapid test results are required to shorten isolation from ten to seven days.

However, for everyone in the U.S. to be able to rapid test out of isolation, the country would need a far greater supply of those tests than we currently have available. This Twitter thread, by epidemiologist Matt Ferrari, explains the challenges posed by limited rapid testing:

Ferrari argues that the CDC guidance makes sense, given the information and resources currently available in the U.S., as well as the fact that simpler rules are easier to follow. Still, I personally would say that, if you have the rapid tests available to test out of isolation, you should.

More Omicron reporting