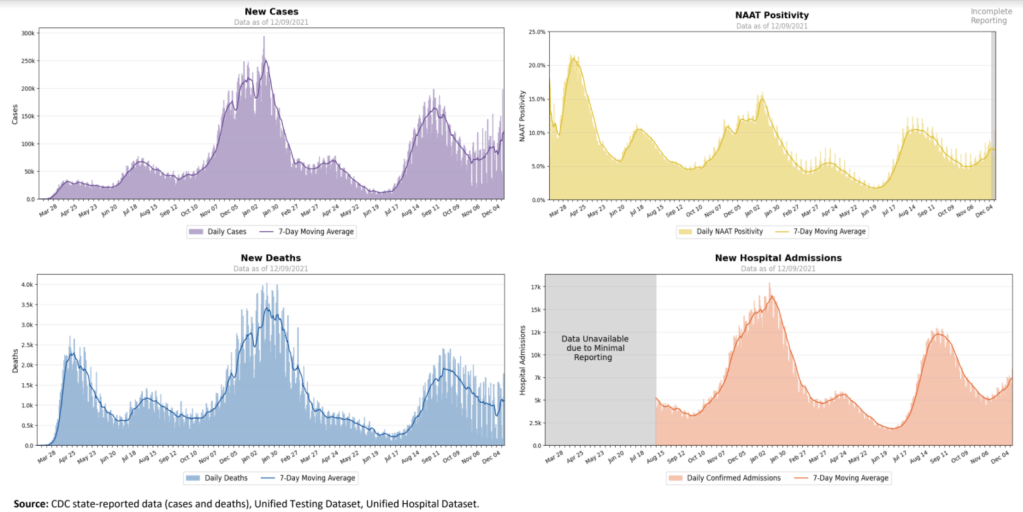

This past Monday, President Biden gave a speech about the Omicron variant. He told America that Omicron is “cause for concern, not a cause for panic,” and thanked the South African scientists who alerted the world to this variant. (Though a travel ban is not a great way to thank those scientists!)

Towards the end of the speech, he said: “We’re throwing everything we can at this virus, tracking it from every angle.” Which I, personally, found laughable. As I’ve pointed out in a previous post about booster shots, the U.S.’s anti-COVID strategy basically revolves around vaccines, and has for most of 2021.

My Tweet about Biden’s vaccine-only strategy got more attention than I’m used to receiving on the platform, so I thought it was a worthwhile topic to expand upon in the COVID-19 Data Dispatch. Why aren’t vaccines enough to address Omicron—or our current surge, for that matter—and what else could the Biden administration be doing to slow the coronavirus’ spread?

Why aren’t vaccines enough?

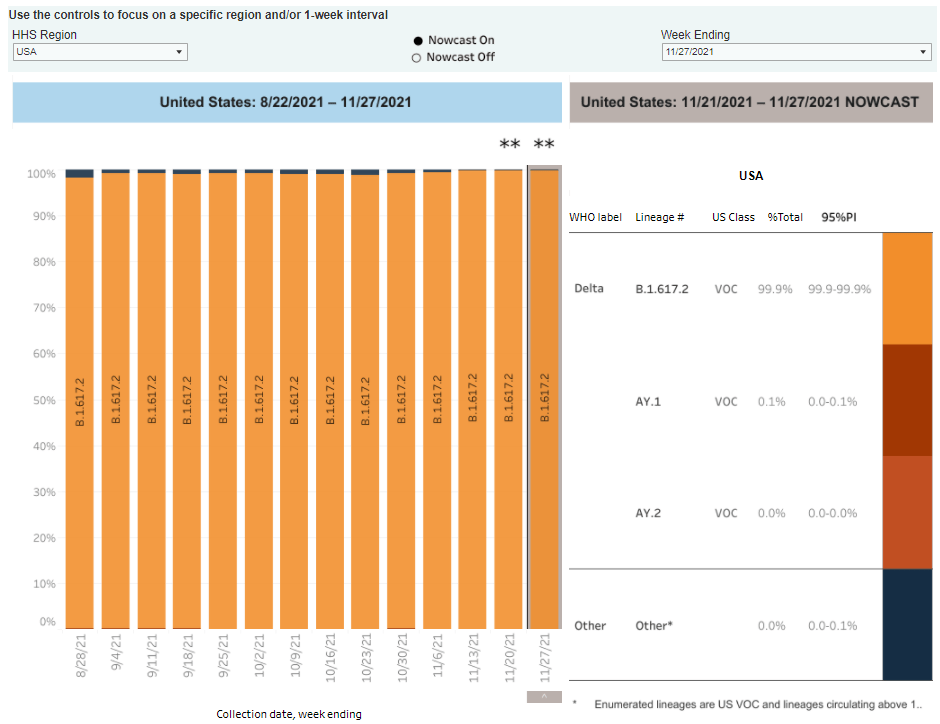

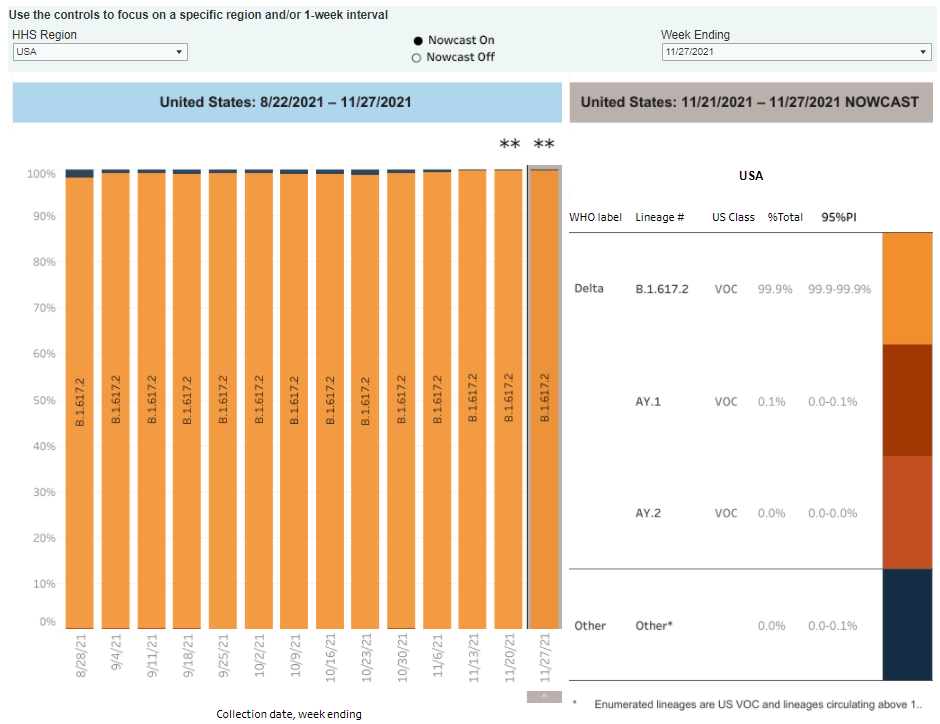

Prior to Delta’s spread, there was some talk of reaching herd immunity: perhaps if 70% or 80% of Americans got fully vaccinated, it would be sufficient to tamp down on the coronavirus. But Delta’s increased capacity to spread quickly, combined with the vaccines’ decreased capacity to protect against infection and transmission, have shown that vaccines are not enough to eradicate the virus.

In thinking about this question, I returned to an article that Ed Yong wrote for The Atlantic back in August:

Here, then, is the current pandemic dilemma: Vaccines remain the best way for individuals to protect themselves, but societies cannot treat vaccines as their only defense. And for now, unvaccinated pockets are still large enough to sustain Delta surges, which can overwhelm hospitals, shut down schools, and create more chances for even worse variants to emerge. To prevent those outcomes, “we need to take advantage of every single tool we have at our disposal,” [Shweta Bansal of Georgetown University] said. These should include better ventilation to reduce the spread of the virus, rapid tests to catch early infections, and forms of social support such as paid sick leave, eviction moratoriums, and free isolation sites that allow infected people to stay away from others.

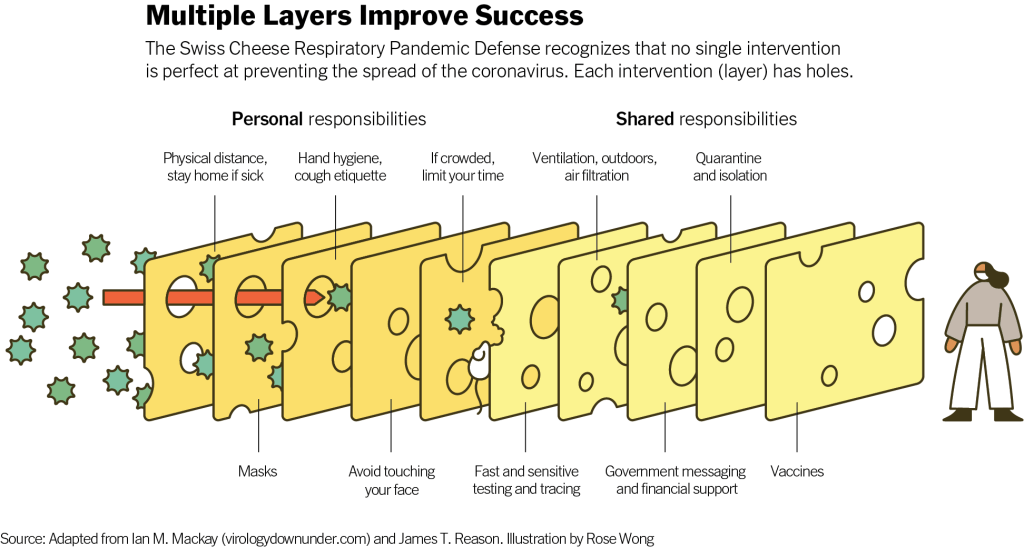

Remember that Swiss cheese model of pandemic interventions? Vaccines may be the best protection we have against the coronavirus, but they’re still just one layer of protection. All the other layers—masks, testing, ventilation, etc.—are still necessary, too. Especially when we’re dealing with a new variant that might not respond as well to our vaccines.

What we could do: better masks

One strategy that we could employ against Omicron, as well as against the current Delta surge, is better masks. While cloth masks certainly make it less likely for the coronavirus to spread from one person to another, their efficacy varies greatly depending on the type of material, the number of layers, and the mask’s fit.

N95 masks do the best job at stopping the coronavirus from spreading, followed by KN95 masks. Surgical masks do a better job than cloth masks, but making sure these masks fit properly can be a challenge for some people (including yours truly, who has a very narrow face!). Layering a surgical mask and cloth mask may be a safer option to get both good fit and protection, though two layers of mask can be challenging to wear for long periods of time.

Some experts have recommended that the U.S. mail N95 or KN95 masks to all Americans, or at least require these masks in high-risk areas, such as on flights. Germany and other European countries established similar requirements last summer.

What we could do: more widely available testing

In many countries—including the U.K., Germany, India, and others—rapid tests are freely available. Here in the U.S., on the other hand, the tests are quite expensive (often upwards of $10 for one test) and difficult to find, with pharmacies often limiting the number of packages that people can buy at once.

Biden has attempted to increase rapid testing access as part of his latest COVID-19 plan: in January, private insurance companies will be required to cover the cost of rapid tests. But this doesn’t solve the supply issue, and it doesn’t really make the tests more accessible, either. The measure would still require people to buy tests out of pocket, then fill out insurance reimbursement forms to maybe get their money back. Can you imagine anyone actually doing this?

In addition, as some experts have pointed out, the people most likely to need rapid tests—essential workers and others in high-risk environments—are also those less likely to have insurance. Biden is also distributing some rapid tests to community health centers, but that’s not enough to meet the need here.

Ideally, the Biden administration would mail every American a pack of, like, 20 rapid tests, along with that pack of N95 or KN95 masks I mentioned above. Free of charge.

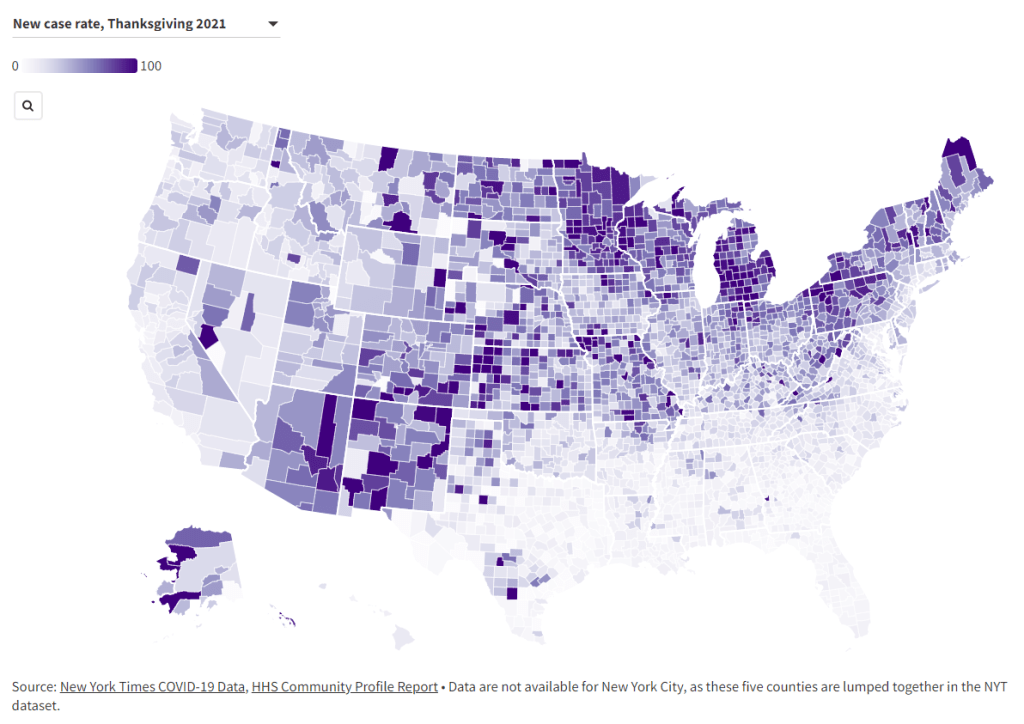

And at the same time, of course, we need more readily available PCR testing. Even in New York City, which has a better testing infrastructure than most other parts of the country, the lines at free testing sites are getting long again as cases go up. Any American who wants to get tested should be able to easily make an appointment within a day or two, and get their results within another day after that.

Increased testing is not only important for identifying Omicron cases (and cases of any other new variant); it’s also key for the Merck and Pfizer antiviral treatments due to be approved in the U.S. soon. Without efficient testing, patients won’t be able to start these treatments within days of their symptoms starting.

What we could do: improve genetic surveillance

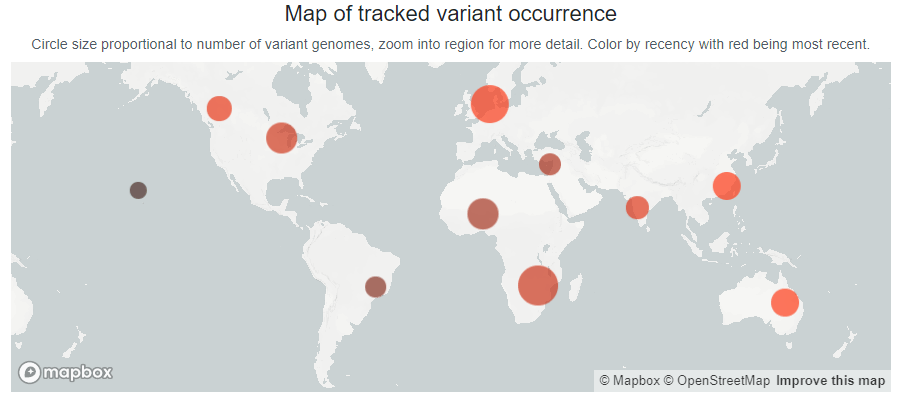

The U.S. is doing a lot more coronavirus sequencing than we were in early 2021: we’ve gone from under 5,000 cases sequenced a week to over 80,000. The CDC worked with state and local health agencies, as well as research organizations and private companies, to increase sequencing capacity across the country.

But that capacity is still concentrated in specific states and cities, as I noted in the previous post. In a recent STAT News story on sequencing, Megan Molteni writes:

Urban centers close to large academic centers tend to be well covered, while rural areas are less so. That means public health departments in large parts of the country are still flying blind, even as they are figuring out ways to prioritize Omicron-suspicious samples.

A lack of testing compounds this problem. If someone doesn’t confirm their COVID-19 case with a PCR test, their genetic information will never make it to a testing lab, much less a sequencing lab. While rapid tests are very useful for quickly finding out if you’re infected with the coronavirus, you need a PCR test for your information to actually be entered into the public health system.

In addition, even where the U.S. is sequencing a lot of samples, the process can take weeks. Vox’s Umair Irfan writes:

Still, it takes the US a median time of 28 days to sequence these genomes and upload the results to international databases. Contrast that with the United Kingdom, which sequences 112 genomes per 1,000 cases, taking a median of 10 days to deposit their results. A delay of only a few days in detection can give variants time to silently spread within communities and across borders.

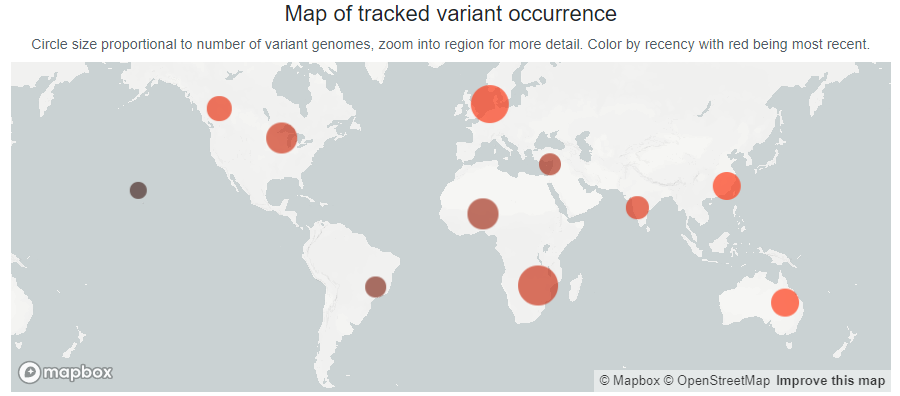

Despite sequencing shortfalls in the U.S., we’re still doing much more surveillance than the majority of countries. Many nations in Africa, Asia, South America, and other parts of the world are sequencing fewer than 10 cases per 1,000, Irfan reports. As the U.S. should be doing more to get the world vaccinated, the U.S. should also do more to help other countries increase their sequencing capacity—monitoring for the variants that will inevitably follow Omicron.

What we could do: stricter domestic travel requirements

Starting on Monday, all international travelers coming into the U.S. by air will need to show a negative COVID-19 test, taken no more than one day before their flight. This includes all travelers regardless of nationality or vaccination status. At the same time, any non-U.S. citizens traveling into the country must provide proof of their vaccination against COVID-19.

But travelers flying domestically don’t face any such requirements. There are mask mandates on airplanes, true, but people can wear cloth masks, often pulled down below their noses, and airports tend to have limited enforcement of any mask rules.

Both experts and polls have supported requiring vaccination for domestic air travel, though the Biden administration seems very hesitant to put this requirement in place. Speaking for myself, I felt very unsafe the last time I flew domestically. A vaccine mandate for air travel would make me much more likely to fly again.

What we could do: more social support

In the U.S., a positive COVID-19 test usually means that you’re in isolation for 10 to 14 days, along with everyone else in your household. This can pull kids out of school, and pull income from families. As has been the case throughout the pandemic, support is needed for people who test positive, whether that’s a safe place to isolate for two weeks, grocery delivery, or rapid tests for the rest of the household.

This type of support could make people actually want to get tested when they have symptoms or an exposure risk, rather than avoiding the public health system entirely.

More variant reporting