By Betsy Ladyzhets

In Port Orford, Oregon, it’s a quick walk from the elementary and middle school building to the town library—the two buildings are right down the street from each other. In fact, the town library and school are linked by more than geography, since the school district’s two libraries became part of the Port Orford library system in 2017. The town’s library system stepped in to assist the district in buying books, organizing the collection, and other management tasks.

Much like how town librarians stepped in to save the school libraries in 2017, they also provided crucial space, books, wifi, and activities to students during the pandemic. The school-library partnership exemplifies the close-knit community of the two small, coastal towns making up the Port Orford-Langlois School District.

District parents and other community members additionally stepped up to provide homemade face masks for teachers and staff. The district built up community trust and used a cautious, step-by-step reopening strategy to make it through the 2020-2021 school year with zero cases identified in school buildings.

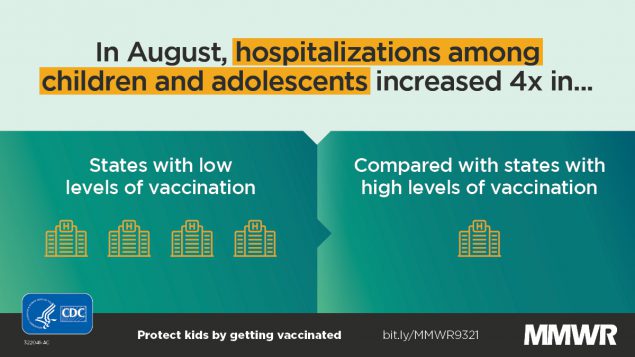

The Port Orford-Langlois School District is the subject of the fourth profile in the COVID-19 Data Dispatch’s “Opening” series. Alongside four other school communities, we selected it because the majority of the district’s students returned to in-person learning during the 2020-2021 school year — and officials identified COVID-19 cases in under 5% of the student population. (According to the CDC, about 5% of school-aged children in the U.S. contracted COVID-19 between the start of the pandemic and early August 2021.)

Demographics for Port Orford, Oregon

American Community Survey 2019 5-year estimates

- Population: 1,000

- Race: 94.7% white, 2.0% Native American, 3.4% two or more races, 1.5% Hispanic/Latino

- Education: 92.8% have high school degree, 11.0% have associate’s degree, 21.5% have bachelor’s degree

- Income: $27,500 is median household income, 27.5% in poverty

- Computer: 87.6% have a computer, 77.0% have broadband internet1

- Free lunch: 68.9% of students receive free or reduced-price lunch2

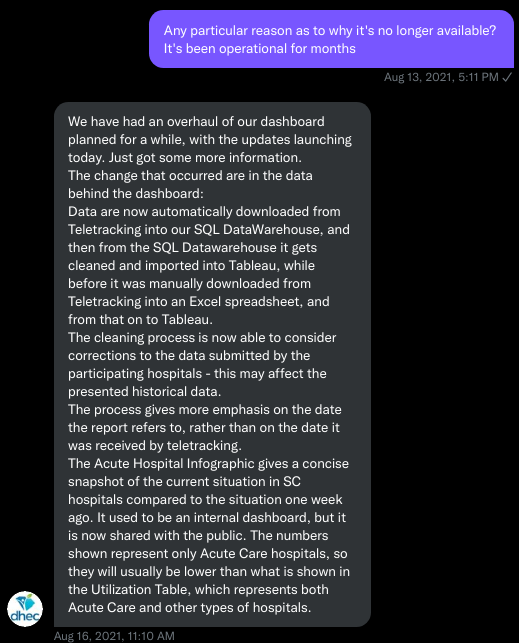

COVID-19 stats for Port Orford-Langlois School District 2CJ

- Total enrollment: 205 students3

- In-person enrollment: Estimated 85%-90% at the start of the school year (K-3 students only), 95% at the end (all grades)3

- Total cases, 2020-2021 school year: 0 cases reported4

1Source: County-level statistic

2Source: National Center for Education Statistics

3Source: Interview with Principal Krista Nieraeth

4Source: Reported by Oregon Health Authority

Library partnership and community

Both of the towns in this Oregon school district are tiny. Port Orford has a population of about 1,000, and Langlois has an even smaller population of 135. The district is made up of two schools: a high school and a K-8 school, where class sizes tend to be under 20 students. The two schools have a total enrollment of about 200 students combined. Staffers at the district wear multiple hats — Krista Nieraeth, for instance, serves as principal for both schools.

In these two small towns, communication between school parents and administrators was direct — and personal. Nieraeth recalled how she often received information about students who needed to quarantine: “I would get a Facebook message [from a parent] at eight o’clock at night going, what do I do?” Some parents also called her personal cell number to ask questions or alert her to COVID-19 symptoms in their households, while district teachers had individual calls with parents before classes started. This level of direct communication reflected trust between the community and the district’s administration.

One example of community partnership was the district’s connection to the Port Orford Public Library, which manages the school district’s library system. Starting in fall 2020, the library hosted IT specialists and teachers from the school in one of the library’s conference rooms. Students were able to come get technological support or a bit of face-to-face homework help.

The library later dedicated more spaces for after-school homework help, allowing families to come in and utilize the free wifi. Both the library and school buildings also kept their wifi turned on, so that families could sit in their parking lots and use it from their cars; the library’s wifi was on 24/7. Similarly to Garrett County in Maryland, the geography of this rural district makes broadband access inaccessible for many families.

“The biggest feedback I had was a wish for longer hours,” Library Director Denise Willms said, when asked how district families responded to the library’s services. Due to low staffing, the library was unable to operate a full seven-days-a-week schedule. Willms additionally noted that the library does not have a great ventilation system or easily-openable windows — and unlike school districts across the country, she was unable to access a government grant for ventilation updates.

Librarians and district staff ultimately brought services from the library directly to students. The school libraries were unavailable for browsing (because they were temporarily used as large classrooms), so library staff and teachers coordinated book delivery directly to classrooms. Kari Hansen, the K-8 school’s library coordinator, recalled using gloves to handle the books and reading out story descriptions to students, so that they could learn about their options at a distance before making a reading choice.

The Port Orford youth services librarian, Cheryl Frances, and school staff also produced take-home activity kits for students. The library’s kits included literacy, dinosaurs, and other STEAM learning materials. Parents could pick these activity packs up at the library, and when extras were available, library staff took them over to the school. The kits served as a way to remind students that “the library is here,” Frances said.

Social studies, history, and economics teacher Phoebe Skinner observed that these take-home activities were very popular with students and parents alike. Since the kits had “everything you need” right in the package, she said, overwhelmed parents didn’t need to hunt down extra supplies or do any other additional labor. The district additionally ran its own virtual events, such as a movie night and bingo games.

Reflecting on the school-library partnership, Willms — the library director — said that her experience embodied: “students first, community first, ego second.” Principal Nieraeth similarly said that the library, along with churches and other community civic organizations, “really would help step up and ask us, ‘What do you need?’”

“Playing it safe”

Similarly to other districts profiled in this project, Port Orford-Langlois prioritized getting students back in physical classrooms during the COVID-19 pandemic. To prepare for that reopening, Nieraeth said, she and other staffers focused on spacing and ventilation. After using tape to map out every classroom in seven-by-five-foot blocks, the staff put a desk in each space.

The staff also prioritized ventilation: windows needed to be open in each classroom. In some cases, classroom assignments were shuffled around to allow proper social distancing. One class with over 20 students, for example, was moved into the library.

In addition to these precise preparations, the district opted to delay its fall 2020 semester by two weeks for extra prep time. Then, age groups were brought back to classrooms in intervals to test out safety measures and build trust in the community.

The first phase of this reopening was the youngest students, grades kindergarten through third grade. Those younger students “needed that stability” of in-person learning, Nieraeth said.

After six weeks of the youngest children in classrooms, case numbers were low enough both in the school district itself and in surrounding Curry County to bring more students back: grades four through six. Administrators had planned to bring back middle and high school students six weeks after that, but by that point, the winter COVID-19 surge had hit Oregon, leading the district to opt for caution and continue virtual learning for older students.

Nieraeth estimated that, at the start of the fall semester, 10% to 15% of the K-3 students chose all-remote learning. But, throughout the semester, more families decided to go back in person, as they saw that the district adhered to safety protocols while also letting kids play together. Parents also developed trust in the district by watching Nieraeth share district updates on social media and respond to parents’ questions.

In addition to basic safety measures like social distancing and ventilation, the district barred visitors from the school buildings, conducted daily temperature and symptom checks, and encouraged lots of handwashing and sanitation.

“My desk had never been cleaner in 20 years of teaching,” said Skinner, the social studies, history, and economics teacher.

Masks were required for all students and staff as well. Nieraeth said she was “pleasantly surprised” to see that even the youngest children wore their masks responsibly. She credited this, in part, to the district’s parents, who modeled mask-wearing for their children — even though the community leans conservative, and parents may not have been overly enthusiastic about masking themselves.

Precautions continue into fall 2021

When the spring semester started in February, middle and high school students were finally able to return to classrooms. Skinner noted that a significant batch of students returned in March, after older family members in their households were able to get vaccinated. By the end of the year, she said, out of 60 to 70 students in her social studies classes, all but eight were attending class in person. Principal Nieraeth similarly estimated that about 95% of the district’s students were attending school in person by the end of the spring semester.

Overall, the safety measures and low community spread helped the Port Orford-Langlois schools avoid outbreaks. The Oregon Health Authority did not identify a single case in the district for the entire 2020-2021 school year; Principal Nieraeth confirmed this statistic.

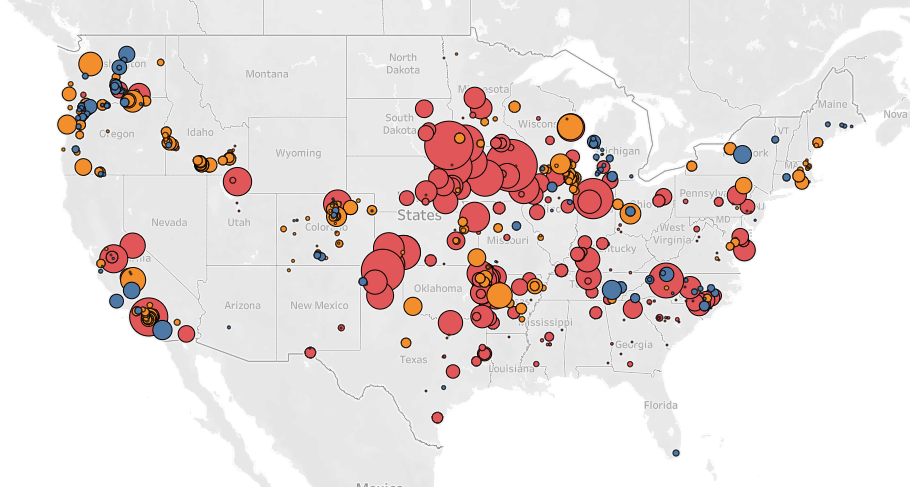

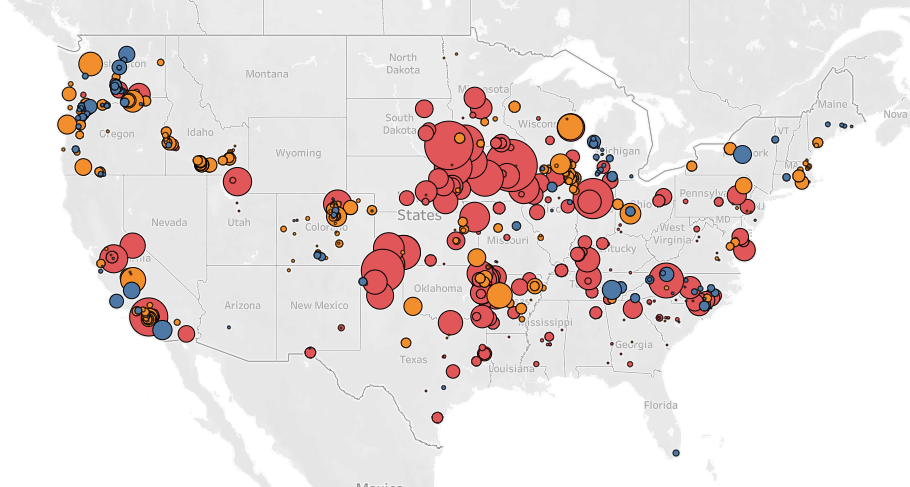

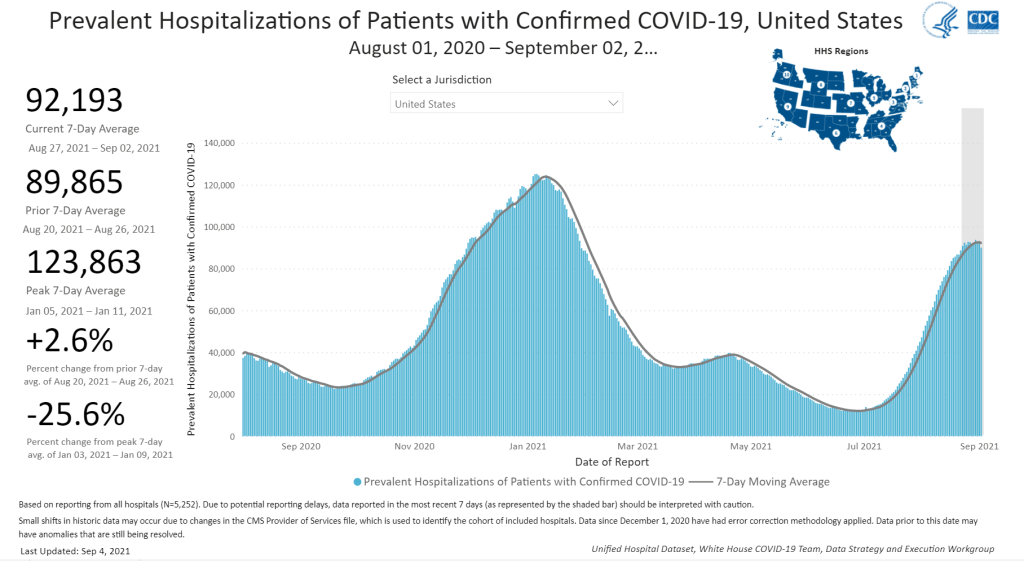

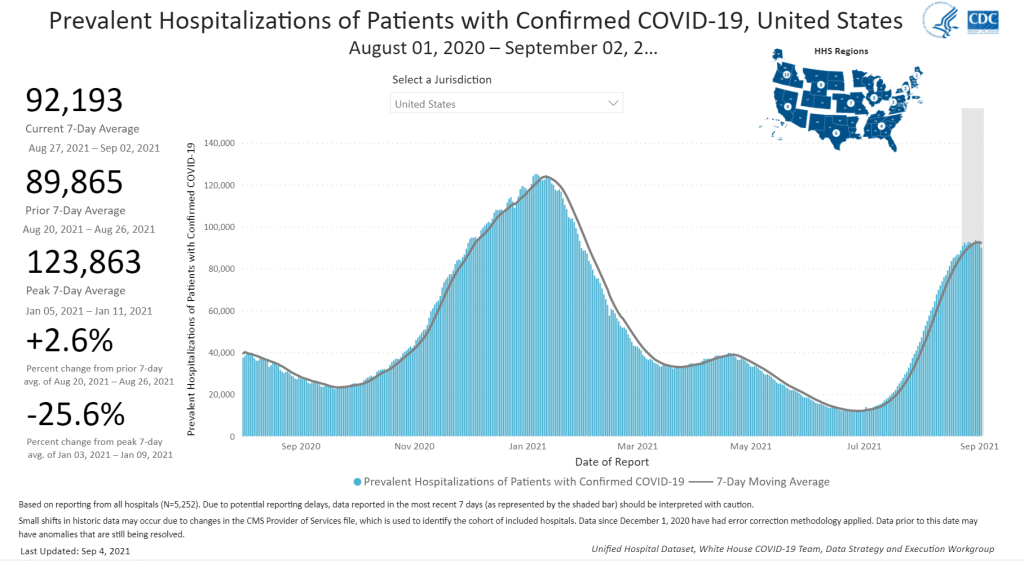

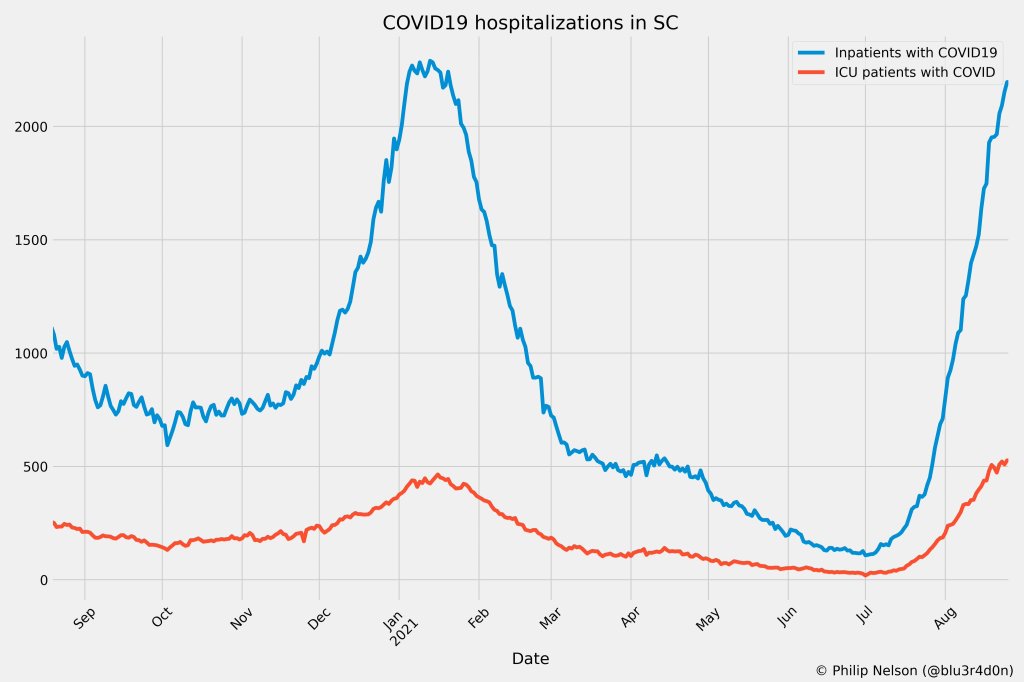

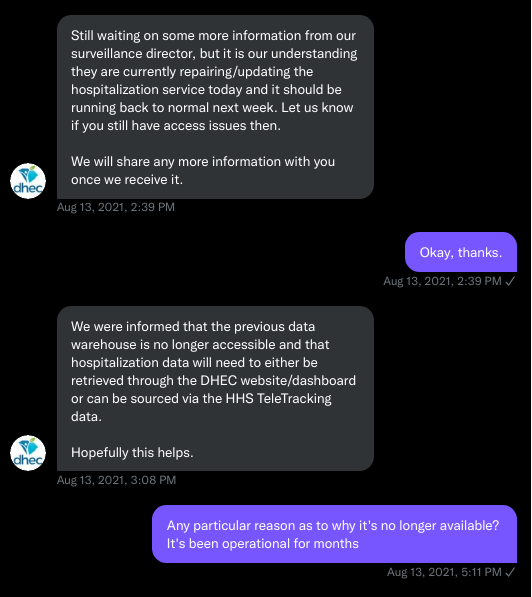

In fall 2021, the Port Orford-Langlois district is continuing similar safety measures to last year, including required masks. But this semester is less likely to proceed with zero outbreaks: the surrounding county, like much of Oregon, is now seeing some of its highest case rates of the pandemic. And, in mid-August, this county reported more cases per person than any other in the state. As of September 1, 51% of county residents are fully vaccinated, per Oregon state data; teachers and staff have until October 18 to comply with a state vaccine mandate.

In a follow-up interview on Sept. 2 — four days into the new school year — Principal Nieraeth said her district was following all the protocols that worked well last year. “We’re working with our families and really reliant on them to help us ensure that we’re being safe at school,” she said.

The COVID-19 Data Dispatch’s “Opening” series is available for other publications to republish, free of charge. If you or your outlet is interested in publishing any part of this series, please contact betsy@coviddatadispatch.com.

Edit, Sept. 7, 2021: An earlier version of this story misrepresented the activity kits produced by the Port Orford Public Library; the story has been updated with accurate examples.

More from the Opening series