- State vaccination reporting: Yesterday, I updated the COVID-19 Data Dispatch page detailing how every state is tracking vaccination. Notably, 15 states now include counts of third doses (or “additional doses,” or “booster shots”) in their vaccine dashboards and reports. A couple of those states (Colorado, Mississippi, New Jersey) are even reporting demographic breakdowns of the residents that have received third doses. I expect that more states will add these metrics to their vaccine reports in the coming weeks.

- COVID-19 cases and deaths, urban vs. rural counties: A new report from the RUPRI Center for Rural Health Policy Analysis at the University of Iowa demonstrates the disproportionate impact that COVID-19 is now having on rural communities. The rate of COVID-19 deaths in rural areas is now twice what it is in urban areas. For context about and data visualizations sourcing this report, see this KHN article by Lauren Weber.

- School District Operational Status: Research organization MCH Strategic Data has compiled detailed data on the operational status of school districts across the country—fully in-person, fully remote, or hybrid. The dashboard also includes information on school mask policies and summary data by state. (H/t Your Local Epidemiologist.)

- State-level analysis of charter school trends: The National Alliance for Public Charter Schools analyzed changes to school enrollment in every state during the 2020-2021 school year, focusing on drops in district public school enrollment and rises in charter school enrollment. Oklahoma had the highest charter school gain, with a whopping 78% enrollment increase.

Blog

-

Featured sources, October 3

-

Answering your COVID-19 questions

The Delta surge is waning. Will this be the last big surge in the U.S., or will we see more? This question and more, answered below; chart from the CDC. Last week, I asked readers to fill out a survey designed to help me reflect on the COVID-19 Data Dispatch’s future. Though the Delta surge—and the pandemic as a whole—is far from over, I’m considering how this publication may evolve in a “post-COVID” era. Specifically, I’m thinking about how to continue serving readers and other journalists as we prepare for future public health crises.

Thank you to everyone who’s filled out the survey so far! I really appreciate all of your feedback. If you haven’t filled it out yet, you can do so here.

Besides some broader questions about the CDD’s format and topics we may explore in the future, the survey asked readers to submit questions that they have about COVID-19 in the U.S. right now. In the absence of other major headlines this week, I’m devoting this week’s issue to answering a few of those questions.

Should I get a booster shot? If so, should it be a different one from the first vaccine I got? When will my kids (5-11) likely be eligible?

I am not a doctor, and I’m definitely not qualified to give medical advice. So, the main thing I will say here is: identify a doctor that you trust, and talk to them about booster shots. I understand that a lot of Americans don’t have a primary care provider or other ways to easily access medical advice, though, so I will offer some more thoughts here.

As I wrote last week, we do not have a lot of data on who’s most vulnerable to breakthrough COVID-19 cases. We do know that seniors are more vulnerable—this is one point where most experts agree. We know that adults with the same health conditions that make them more likely to have a severe COVID-19 case without a vaccine (autoimmune conditions, diabetes, kidney disease, etc.) are also more vulnerable to breakthrough cases, though we don’t have as much data here. And we know that vaccinated adults working in higher-risk locations like hospitals, nursing homes, and prisons are more likely to encounter the coronavirus, even if they may not necessarily be more likely to have a severe breakthrough case.

The FDA and CDC’s booster shot guidance is intentionally broad, allowing many Americans to receive a booster even if it is not necessarily needed. So, consider: what benefits would a booster shot bring you? Are you a senior or someone with a health condition that makes you more likely to have a severe COVID-19 case? Do you want to protect the people you work or live with from potentially encountering the coronavirus?

If you answered “yes” to one of those questions, a booster shot may make sense for you. And, while you may be angry about global vaccine inequity, one individual refusal of a booster shot would not have a significant impact on the situation. Rather, many vaccine doses in the U.S. may go to waste if not used for boosters. But again: talk to your doctor, if you’re able to, about this decision.

Currently, Pfizer booster shots are available for people who previously got vaccinated with Pfizer. The FDA’s vaccine advisory committee is meeting soon to discuss Moderna and Johnson & Johnson boosters: they’ll discuss Moderna on October 14 and J&J on October 15. Vaccine approval in the U.S. depends upon data submission from vaccine manufacturers—and vaccine manufacturers have not been studying mix-and-match booster regimens—so coming approvals will likely require Americans to get a booster of the same vaccine that they received initially. We will likely see more discussion of mix-and-match vaccinations in the future, though, as more outside studies are completed.

As for when your kids will likely be eligible: FDA’s advisory committee is meeting to discuss Pfizer shots for kids ages 5 through 11 on October 26. If that meeting—and a subsequent CDC meeting—goes well, kids may be able to get vaccinated within a week of that meeting. (Potentially even on Halloween!)

Why don’t people get vaccinated and how can we make them?

I got a couple of questions along these lines, asking about vaccination motivations. To answer, I’m turning to KFF’s COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor, a source of survey data on vaccination that I (and many other journalists) have relied on since early 2021.

KFF released the latest round of data from its vaccine monitor this week. Here are a few key takeaways:

- The racial gap in vaccinations appears to be closing. KFF found that 71% of white adults have been vaccinated, compared to 70% of Black adults and 73% of Hispanic adults. Data from the CDC and Bloomberg (compiling data from states) similarly show this gap closing, though some parts of the country are more equitably vaccinated than others.

- A massive partisan gap in vaccinations remains. According to KFF, 90% of Democrats are vaccinated compared to just 58% of Republicans. This demonstrates the pervasiveness of anti-vaccine misinformation and political rhetoric among conservatives.

- Rural and younger uninsured Americans also have low vaccination rates (62% and 54%, respectively). Both rural and uninsured people have been neglected by the U.S. healthcare system and face access barriers; for more on this topic, I recommend this Undark article by Timothy Delizza.

- Delta was a big vaccination motivator. KFF specifically asked people who had gotten their shots after June 1 why they chose to get vaccinated. The most popular reasons were, in order: the increase in cases due to Delta (39%), concern about reports of local hospitals and ICUs filling with COVID-19 patients (38%), and knowing someone who got seriously ill or died from COVID-19 (36%).

- Mandates and social pressures were also vaccination motivators. 35% of KFF’s recently vaccinated survey respondents said that a big reason for their choice was a desire to participate in activities that require vaccination, like going to the gym, a big event, or traveling. 19% cited an employer requirement and 19% cited social pressure from family and friends.

The second part of this question, “how can we make them?”, reflects a dangerous attitude that has permeated vaccine conversations in recent months. Yes, it’s understandable to be frustrated with the Americans who have refused vaccination. But we can’t “make” the unvaccinated do anything, and such a forceful attitude may put off people who still have questions about the vaccines or who have faced discrimination in the healthcare system. To increase vaccinations among people who are still hesitant, it’s important to remain open-minded, not condescending. For more: read Ed Yong’s interview with Dr. Rhea Boyd.

That said, we’re now getting a sense of which strategies can increase vaccination: employer mandates, vaccination requirements for public life, and personal experience with the coronavirus. As the Delta surge wanes, it will take more vaccination requirements and careful, open-minded conversations to continue motivating people to get their shots.

What are some things I might say to convince people of Delta’s severity and the need to not relax on masking, distancing, etc?

To answer this, I’ll refer you to the article I wrote about Delta on August 1, as the findings that I discuss there have been backed up by further research.

Personally, there are two statistics that I use to express Delta’s dangers to people:

- Delta causes a viral load 1,000 times higher than the original coronavirus strain. This number comes from a study in Guangzhou, China, posted as a preprint in late July. While viral load does not correspond precisely to infectiousness (there are other viral and immune system factors at play), I find that this “1,000 times higher” statistic is a good way to convey just how contagious Delta is, compared to past variants.

- An interaction of one second is enough time for Delta to spread from one person to another. Remember the 15-minute rule? In spring 2020, being indoors with someone, unmasked, for 15 minutes or more was considered “close contact.” Delta’s increased transmissibility means that an interaction of one second is now enough to be a “close contact.” The risk is lower if you’re vaccinated, but still—Delta is capable of spreading very quickly in enclosed spaces.

You may also find it helpful to discuss rising numbers of breakthrough cases in the U.S. While vaccinated people continue to be incredibly well protected against severe disease and death caused by Delta, the vaccines are not as protective against coronavirus infection and transmission. (They are protective to some degree, though! Notably, coronavirus infections in vaccinated people tend to be significantly shorter than they are in the unvaccinated, since immune systems can quickly respond to the threat.)

It’s true that rising breakthrough case numbers are, in a way, expected—as more people get vaccinated, breakthrough cases will naturally become more common, because the virus has fewer and fewer unvaccinated people to infect. But considering the risks of spreading the coronavirus to others, plus the risks of Long COVID from a breakthrough case… I personally don’t want a breakthrough case, and so I continue masking up and following other safety protocols.

What monitoring do we have in place for COVID “longhaulers” and their symptoms/health implications?

This is a great question, and one I wish I could answer in more detail. Unlike COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and other major metrics, we do not have a comprehensive national monitoring system to tell us how many people are facing long-term symptoms from a coronavirus infection, much less how they’re faring. I consider this one of the country’s biggest COVID-19 data gaps, leaving us relatively unprepared to help the thousands, if not millions, of people left newly disabled by the pandemic.

In February, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced a major research initiative to study Long COVID. Congress has provided over $1 billion in funding for the research. This initiative will likely be our best source for Long COVID information in the future, but it’s still in early stages right now. Just two weeks ago, the NIH awarded a large share of its funding to New York University’s Langone Medical Center; NYU is now setting up long-term studies and distributing funding to other research institutions.

As I wrote in the September 19 issue, the NIH’s RECOVER website currently reports that between 10% and 30% of people infected with the coronavirus will go on to develop Long COVID; hopefully research at NYU and elsewhere will lead to some more precise numbers.

While we wait for the NIH research to progress, I personally find the Patient-Led Research Collaborative (PLRC) to be a great source for Long COVID research and data. The PLRC consists of Long COVID patients who research their own condition; it was founded out of Body Politic’s Long COVID support group. This group produced one of the most comprehensive papers on Long COVID to date, based on an international survey including thousands of patients, and has more research currently ongoing.

If you have the means to support Long COVID patients—many of whom are unable to work and facing homelessness—please see the responses to this tweet by PLRC researcher Hannah Davis:

Why is the CDC not doing comprehensive high volumes of sequencing on all breakthrough cases at the very least?

I wish I knew! As I wrote last week (and in several other past issues), the lack of comprehensive breakthrough case data in the U.S. has contributed to a lack of clarity on booster shots, as well as a lack of preparedness for the next variants that may become threats after Delta. The CDC’s inability to track and sequence all breakthrough cases—not just the severe ones—is dangerous.

That said, it is very difficult to track breakthrough cases in a country like the U.S. Consider: the U.S. does not have a comprehensive, national electronic records system for patients admitted to hospitals, much less those who receive COVID-19 tests and other care at outpatient clinics. This lack of comprehensive records makes it difficult to match people who’ve been vaccinated with those who have received a positive COVID-19 test. Thousands, if not millions of Americans are now relying on rapid tests for their personal COVID-19 information—and most rapid tests don’t get entered into the public health records system at all.

Plus, local public health departments are chronically underfunded, understaffed, and burned out after almost two years of working in a pandemic; they have little bandwidth to track breakthrough cases. Many Americans refuse to participate in contact tracing, which hinders the public health system’s ability to collect key information about their cases. And there are other logistical challenges around genomic sequencing; despite new investments in this area, many parts of the country don’t have sequencing capacity, or the information infrastructure needed to send sequencing results to the CDC.

So, if the CDC were tracking non-severe breakthrough cases, they’d likely miss a lot of the cases. But that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be trying, in my opinion.

How safe is it to visit my family for the holidays?

This is another place where I don’t feel qualified to give advice, but I can offer some thoughts. If I were you, I would think about the different ways in which holiday travel might pose risk to me and to the people at the other end of my trip. I would consider:

- Quarantining beforehand. Do your occupation and living circumstances allow you to quarantine for a week, or at least limit your exposure to settings where you might be at risk of catching the coronavirus, before you travel? Can you get a test before traveling?

- Types of travel. Can you make the trip in a car or on public transportation, or do you need to fly? If you need to fly, can you select an airline that has stricter COVID-19 safety requirements? (United recently reported that over 96% of its employees are now vaccinated, for example.) Can you wear a high-quality mask for the flight?

- Quarantining and/or testing upon arrival. Can you spend a couple of days in quarantine once you get to your destination? Would you have access to testing (with results in under 24 hours) upon your arrival, or would you be able to bring rapid tests with you?

- Who you’re spending time with. Among the family you’d be visiting, is everyone vaccinated (besides young children)? If anyone is not vaccinated, could your potential travel be a motivator to help convince them to get vaccinated? Does the group include seniors or people with health conditions that put them at high risk for COVID-19, and if so, can they get booster shots?

- Activities that you do at your destination. Would you be able to have large gatherings outside, or in a well-ventilated space? What else can you do to reduce the risk of these activities?

Like other activities, travel can be relatively safe or fairly dangerous depending on the precautions that you’re able to take, and depending on COVID-19 case rates where you live and at your destination. And, like other activities, your choice to travel or not travel depends a lot on your personal risk tolerance. Nothing is zero-risk right now; each person has a threshold that determines what level of COVID-19 risk they are and are not comfortable taking. Through some self-reflection, you can determine if travel is above or below your risk threshold.

Why are policies so different now than they were at this time last year?

Public health tends to go through cycles of “panic” and “neglect.” Ed Yong’s latest feature goes into the history of this phenomenon:

Almost 20 years ago, the historians of medicine Elizabeth Fee and Theodore Brown lamented that the U.S. had “failed to sustain progress in any coherent manner” in its capacity to handle infectious diseases. With every new pathogen—cholera in the 1830s, HIV in the 1980s—Americans rediscover the weaknesses in the country’s health system, briefly attempt to address the problem, and then “let our interest lapse when the immediate crisis seems to be over,” Fee and Brown wrote. The result is a Sisyphean cycle of panic and neglect that is now spinning in its third century. Progress is always undone; promise, always unfulfilled. Fee died in 2018, two years before SARS-CoV-2 arose. But in documenting America’s past, she foresaw its pandemic present—and its likely future.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. took a nosedive into the “neglect” cycle before we were even finished with the “panic” cycle. Congress has already slashed its funding for future pandemic preparedness, while state and local governments across the country restrict the powers of public health officials. As a result, we’re seeing an “everyone for themselves” attitude at a time when we should be seeing new mask mandates, restrictions on public activities, and other safety measures.

Basically, America decided the pandemic was over and acted accordingly—and if you get COVID-19 now, it’s “your fault for not being vaccinated.” This phenomenon has been especially pronounced in rural areas, which struggled a lot (but saw few cases) during spring 2020 lockdowns and are extremely hesitant to do anything approaching a “lockdown” again.

We need an attitude shift—and more investment in public health—to actually end this pandemic and prepare for the next health crisis. Yong’s feature goes into this in more detail; definitely give that a read if you haven’t yet.

When is this going to be over?!?

Unfortunately, this is very hard to predict—even for the expert epidemiologists and computational biologists who make the models. Check out the CDC’s compilation of COVID-19 case models: most of them agree that cases will keep going down in the coming weeks, but they’re kind of all over the place.

Last week, I summarized two stories—from The Atlantic and STAT News—that discuss the coming winter, and kind of get at this question. It’s possible that cases keep declining from their present numbers, and that the Delta surge we just faced is the last major surge in the U.S. It’s also possible that a new variant arises out of Delta and sends us into yet another new surge. If that happens, more people will be protected by vaccination and prior infection, but healthcare systems could come under strain once again.

As long as the coronavirus continues spreading somewhere in the world, it will continue to pose risk to everyone—able to cause new outbreaks and mutate into new variants. This will continue until the vast majority of the world is vaccinated. And then, at some point, the coronavirus will probably become endemic, meaning it persists in the population at some kind of “acceptable” threshold. Just like the flu.

Dr. Ellie Murray, epidemiologist at Boston University’s School of Public Health, explained how a pandemic becomes endemic in a recent Twitter thread:

Dr. Murray points out that, even when a disease reaches endemic status, tons of scientists and public health workers will still continue to monitor it. This is the case for the flu—think about all of the effort that goes into a given year’s flu shot!—and it will likely be the case for COVID-19.

In short, public health leaders need to figure out what level of COVID-19 transmission is “acceptable” and how we will continue to monitor it. This needs to happen at both U.S. and global levels. And, thanks to our vaccine-rich status, it’ll likely happen in the U.S. long before it happens globally.

Again, if you haven’t filled out the survey yet, you can do so here. I may answer more questions next week!

-

National numbers, October 3

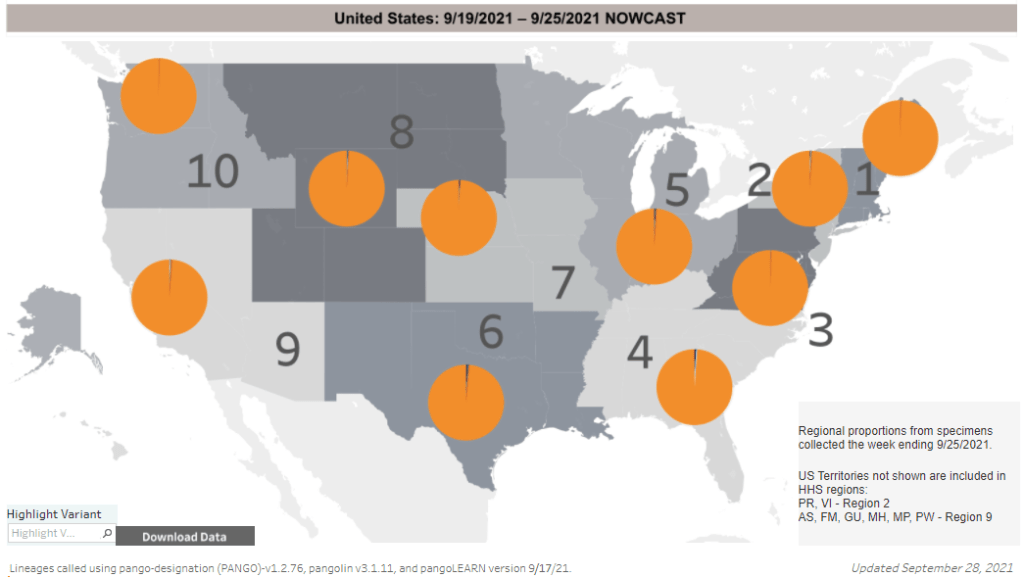

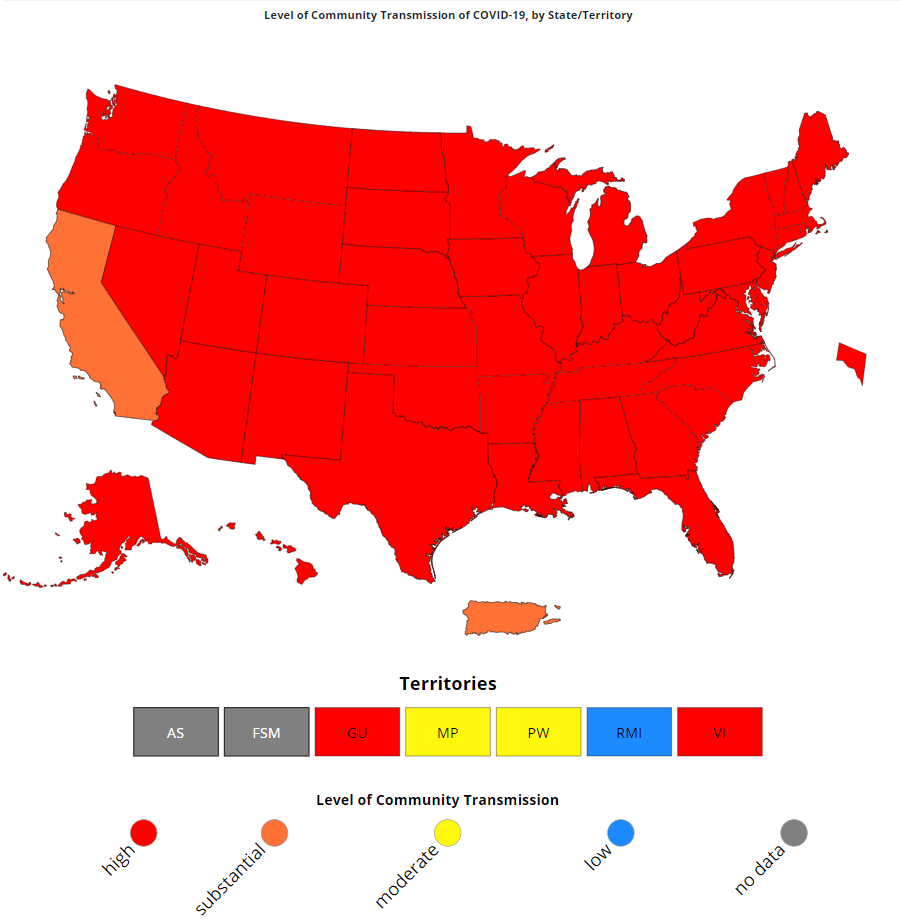

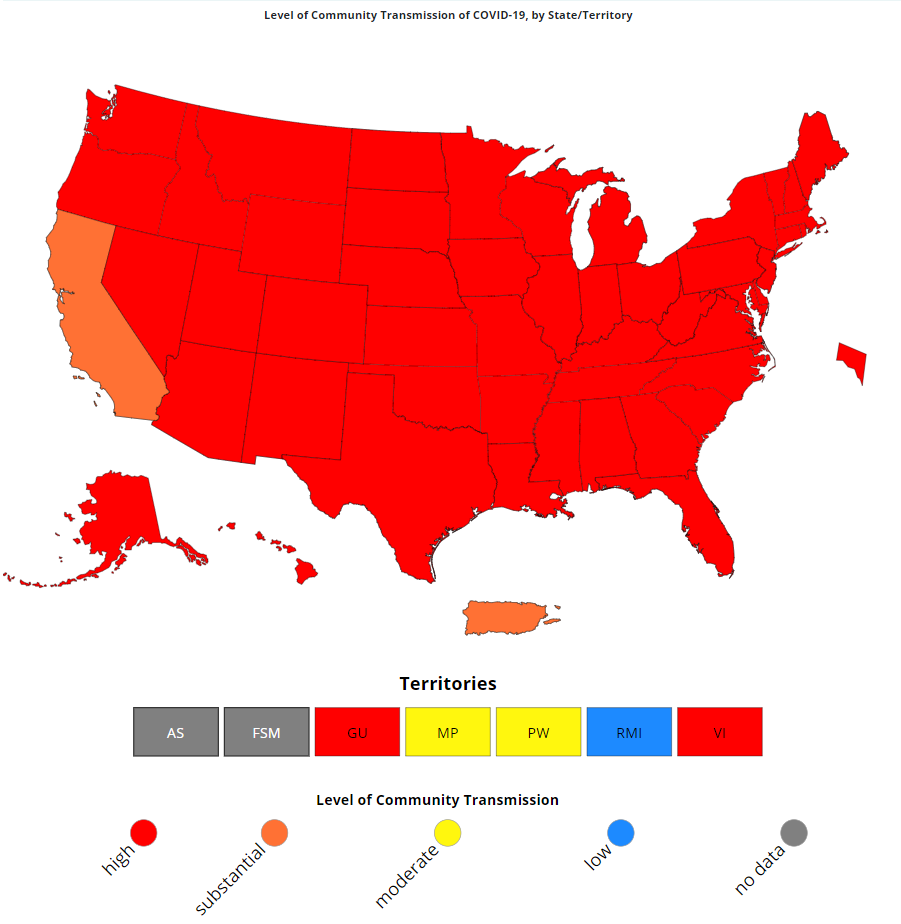

Delta dominates throughout the U.S. The CDC’s variant map has looked like this for a few weeks now. In the past week (September 25 through October 1), the U.S. reported about 750,000 new cases, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 106,000 new cases each day

- 227 total new cases for every 100,000 Americans

- 13% fewer new cases than last week (September 18-24)

Last week, America also saw:

- 58,000 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals (18 for every 100,000 people)

- 10,000 new COVID-19 deaths (3.2 for every 100,000 people)

- 99% of new cases are Delta-caused (as of September 25)

- An average of 800,000 vaccinations per day (including booster shots; per Bloomberg)

COVID-19 cases continue to go down in the U.S.; by next week, the country will likely be back under 100,000 new cases a day. Hospitalizations are also dropping: this week, the number of COVID-19 patients currently hospitalized across the U.S. dropped about 12%, to 72,000.

But over 10,000 COVID-19 deaths were reported this week, for the third week in a row. Many of these deaths likely occurred earlier in the Delta surge, but showed up in the numbers more recently due to reporting lags.

The U.S. passed 700,000 COVID-19 deaths this week, many of them unvaccinated. To quote Ed Yong’s latest feature: “Every adult in the U.S. has been eligible for vaccines since mid-April; in that time, more Americans have died of COVID-19 per capita than people in Germany, Canada, Rwanda, Vietnam, or more than 130 other countries did in the pre-vaccine era.”

Alaska is now the number one COVID-19 hotspot in the country. According to Friday’s Community Profile Report, the state saw almost 1,200 new COVID-19 cases for every 100,000 residents in the week ending September 29. That’s twelve times higher than the CDC’s threshold for “high transmission,” 100 new cases for every 100,000 people in a week.

Hospitals in Alaska are completely overwhelmed. The state currently has about 40% more COVID-19 patients in hospitals than it did at the peak of the winter surge. In a recent video posted to Facebook and shared with local leaders, a nurse at Fairbanks Medical Hospital describes the dire process of dying from COVID-19—something that has become incredibly common in her workplace. About 50% of Alaska’s population is fully vaccinated.

On the other side of the spectrum, Connecticut has joined California in the “substantial transmission” range. Connecticut saw 98 new cases for every 100,000 people in the past week, while California saw 73 new cases for every 100,000.

Over 99% of new cases in the U.S. are caused by Delta, as has been the case for over a month. Delta has solidly outcompeted the Mu variant, and remains dominant across the country. Will this variant peter out as the surge slowly wanes, or will Delta evolve into another more-dangerous variant? The CDC’s current data makes it hard to look for signals.

-

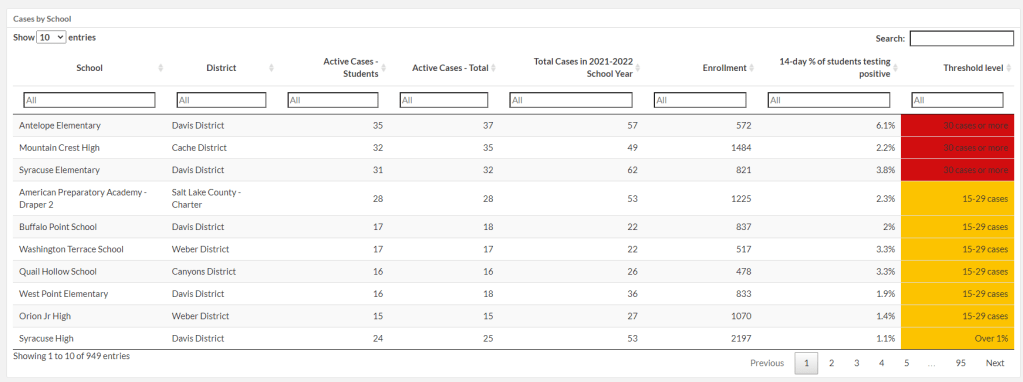

COVID source shout-out: K-12 data in Utah

Utah has expanded its K-12 COVID-19 reporting. This week, I updated the COVID-19 Data Dispatch page detailing how every state is (or isn’t) reporting COVID-19 cases in schools. I was glad to see that several states have resumed data reporting on this important topic after a summer break, though some haven’t resumed yet. (Looking at you, New York.)

I want to give a special shout-out to Utah, which has expanded its K-12 data since spring 2021. This state is now the fourth to report in-person enrollment in schools (after New York, Texas, and Delaware). Utah is also reporting school-specific test positivity rates, providing the share of students who have tested positive in the past two weeks.

It’s not surprising that Utah would expand its school data reporting, because this state is currently pioneering a program called Test to Stay. Schools are required to offer testing to all students when an outbreak occurs, in partnership with their local health departments.

-

Featured sources, September 26

- CDC updates its variant classifications: This one is more of an update than a new source. On Thursday, the CDC updated the list of coronavirus variants that the agency’s scientists are watching. This list now includes three categories: Variants of Concern (or VOCs, which pose a significant threat to the U.S.), Variants of Interest (which may be concerning, but aren’t yet enough of a threat to be VOCs), and Variants Being Monitored (which were previously concerning, but now are circulating at very low levels in the U.S.). Notably, Delta is now the CDC’s only VOC; all other variants are Variants Being Monitored.

- COVID-19 School Data Hub: Emily Oster, one of the leading (and most controversial) researchers on COVID-19 cases in K-12 schools, has a new schools dashboard. The dashboard currently provides data from the 2020-2021 school year, including schools’ learning modes (in-person, hybrid, virtual) and case counts. Of course, data are only available for about half of states. You can read more about the dashboard in this Substack post from Oster.

- Influenza Encyclopedia, 1918-1919: In today’s National Numbers section, I noted that the U.S. has now reported more deaths from COVID-19 than it did from the Spanish flu. If you’d like to dig more into that past pandemic, you can find statistics, historical documents, photographs, and more from 50 U.S. cities at this online encyclopedia, produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine.

-

Our pandemic winter: Stories on what to expect

This week, two of the outlets that I consider to be among the most reliable COVID-19 news sources published stories on our coming pandemic winter. Obviously, you should read both pieces in full, but here are my takeaways.

The first story comes from The Atlantic’s science desk, with a triple-star byline including Katherine J. Wu, Ed Yong, and Sarah Zhang.

This piece focuses on the changing role of vaccination in protecting the U.S. from COVID-19. After a few months of encouraging data, suggesting that vaccines could protect us against coronavirus infection and transmission, we are now back to using COVID-19 vaccines for their initial purpose: preventing severe disease and death. As we see higher numbers of breakthrough cases, we can take comfort in the fact that those cases will rarely lead to hospitalization or death. (Though the risk of Long COVID after vaccination is less known.)

The Atlantic’s article also explains who is now most at risk of COVID-19, and how that risk may shift in the coming months. Right now, unvaccinated children face high risk, especially if they live in communities where most of the adults aren’t vaccinated. But that won’t always be the case:

Relative risk will keep shifting, even if the virus somehow stops mutating and becomes a static threat. (It won’t.) Our immune systems’ memories of the coronavirus, for instance, could wane—possibly over the course of years, if immunization against similar viruses is a guide. People who are currently fully vaccinated may eventually need boosters. Infants who have never encountered the coronavirus will be born into the population, while people with immunity die. Even the vaccinated won’t all look the same: Some, including people who are moderately or severely immunocompromised, might never respond to the shots as well as others.

At the end of the article, the writers touch on variants. Delta is now the world’s major concern, but future variants might develop new mutations and pose new dangers. Yet the writers say that any variant “can be stopped through the combined measures of vaccines, masks, distancing, and other measures that cut the conduits they need to travel.”

The second “pandemic winter” story comes from ace STAT News reporter Helen Branswell. Branswell goes into more detail about potential variant scenarios, outlining what Delta may do and how other mutations may arise as the weather gets colder.

Some modeling efforts suggest that COVID-19 case numbers may stay low once the Delta wave ends, Branswell reports, because the majority of Americans are now fully vaccinated or have some immunity from a prior infection. But if another dangerous variant comes along, we could be in trouble. Still, if cases go up again, we won’t see as many hospitalizations or deaths as we did last winter, thanks to the vaccines.

I personally take comfort in this quotation from computational biologist Trevor Bedford:

“It is likely that we’ll see some wave,” Bedford said. “I would like to think it’s very unlikely to be as big as it was last year.”

Because Delta is causing the vast majority of the world’s COVID-19 cases right now, Branswell reports, future variants would likely arise from Delta. That could mean even more transmissibility or challenges to the human immune system. There’s a lot of uncertainty involved in trying to predict mutations, though. Branswell points out:

Early in the pandemic, coronavirus experts confidently opined that this family of viruses mutates far more slowly than, say, influenza, and major changes weren’t likely to undermine efforts to control SARS-2. But no one alive had watched a new coronavirus cycle its way through hundreds of millions of people before.

Branswell’s story also spends time explaining the potential pressures that COVID-19 could put on the healthcare system if combined with flu or other respiratory viruses. Healthcare workers may need to distinguish COVID-19 cases from flu cases, then treat both with similar equipment.

The story makes a pretty good argument for getting your flu shot now, if it’s available to you. I got mine last week.

-

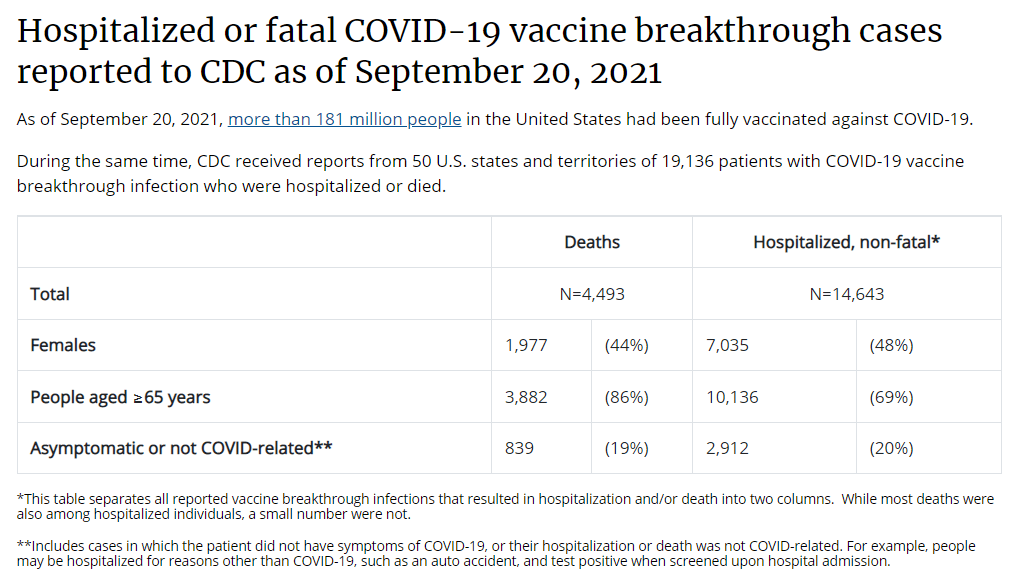

The data problem underlying booster shot confusion

This is all the breakthrough case data that the CDC gives us. Screenshot taken on September 26. This past Thursday, an advisory committee to the CDC recommended that booster doses of the Pfizer vaccine be authorized for seniors and individuals with high-risk health conditions. The committee’s recommendation, notably, did not include individuals who worked in high-risk settings, such as healthcare workers—whom the FDA had included in its own Emergency Use Authorization, following an FDA advisory committee meeting last week.

Then, very early on Friday morning, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky announced that she was overruling the advisory committee—but agreeing with the FDA. Americans who work in high-risk settings can get booster shots. (At least, they can get booster shots if they previously received two doses of Pfizer’s vaccine.)

This week’s developments have been just the latest in a rather confusing booster shot timeline:

Why has this process been so confusing? Why don’t the experts agree on whether booster shots are necessary, or on who should get these extra shots? Part of the problem, of course, is that the Biden administration announced booster shots were coming in August, before the scientific agencies had a chance to review all the relevant evidence.

But from my (data journalist’s) perspective, the booster shot confusion largely stems from a lack of data on breakthrough cases.

Let’s go back in time—back four months, or about four years in pandemic time. In May, the CDC announced a major change in its tracking of breakthrough cases. The agency had previously investigated and published data on all breakthrough cases, including those that were mild. But starting in May, the CDC was only investigating and publishing data on those severe breakthrough cases, i.e. those which led to hospitalization or death.

At the time, I called this a lazy choice that would hinder the U.S.’s ability to track how well the vaccines are working. I continued to criticize this move, when researchers and journalists attempted to do the CDC’s job—but were unable to provide data as comprehensive as what the CDC might make available.

Think about what might have been possible if the CDC had continued tracking all breakthrough cases, or had even stepped up its investigation of these cases through increased testing and genomic sequencing. Imagine if we had data showing breakthrough cases by age group, by high-risk health condition, or by occupational setting—all broken out by their severity. What if we could compare the risk of someone with diabetes getting a breakthrough case, to the risk of someone who works in an elementary school?

If we had this kind of data, the FDA and CDC advisory committees would have information that they could use to determine the potential benefits of booster shots for specific subsets of the U.S. population. Instead, these committees had to make guesses. Their guesses didn’t come out of nowhere; they had scientific studies to review, data from Pfizer, and information from Israel and the U.K., two countries with better public health data systems than the U.S. But still, these guesses were much less informed than they might have been if the CDC had tracked breakthrough cases and outbreaks in a more comprehensive manner.

From that perspective, I can’t really fault the CDC and the FDA for casting their guesses with a fairly wide net—including the majority of Americans who received Pfizer shots in their authorization. There’s also a logistical component here; the U.S. has a lot of doses that are currently going unused (thanks to vaccine hesitancy), and may be wasted if they aren’t used as boosters.

But it is worth emphasizing how a lack of data on breakthrough cases has driven a booster shot decision based on fear of who might be at risk, rather than on hard evidence about who is actually at risk. Other than seniors; the risk for that group is fairly clear.

The booster shot decision casts a wide net. But at the same time, it creates a narrow band of booster eligibility: only people who got two doses of Pfizer earlier in 2021 are now eligible for a Pfizer booster. Recipients of the Moderna and Johnson & Johnson vaccines are still left in the dark, even though some of those people may need a booster more than many people who are now eligible for additional Pfizer shots. (Compare, say, a 25-year-old teacher who got Pfizer to a 80-year-old, living in a nursing home, with multiple health conditions who got Moderna.)

That Pfizer-only restriction also stems from a data issue. The federal government’s current model for approving vaccines is very specific: first a pharmaceutical company submits its data to the FDA, then the FDA reviews these data, then the FDA makes a decision, then the CDC reviews the data, then the CDC makes a decision.

By starting with the pharmaceutical company, the decision-making process is restricted to options presented by that company. As a result, we aren’t seeing much data on mixing-and-matching different vaccines, which likely wouldn’t be profitable for vaccine manufacturers. (Even though immunological evidence suggests that this could be a useful strategy, especially for Johnson & Johnson recipients.)

In short, the FDA and CDC’s booster shot decision is essentially both ahead of evidence on who may benefit most from a booster, but behind evidence for non-Pfizer vaccine recipients. It’s kind-of a mess.

I also can’t end this post without acknowledging that we need to vaccinate the whole world, not just the U.S. Global vaccination went largely undiscussed at the FDA and CDC meetings, even though it is a top concern for many public health experts outside these agencies.

At an international summit this week, President Biden announced more U.S. donations to the global vaccine effort. His administration seems convinced that the U.S. can manage both boosters at home and donations abroad. But the White House only has so much political capital to spend. And right now, it’s pretty clearly getting spent on boosters, rather than, say, incentivizing the vaccine manufacturers to share their technology with the Global South.

I can only imagine this situation getting messier in the months to come.

More vaccine reporting

-

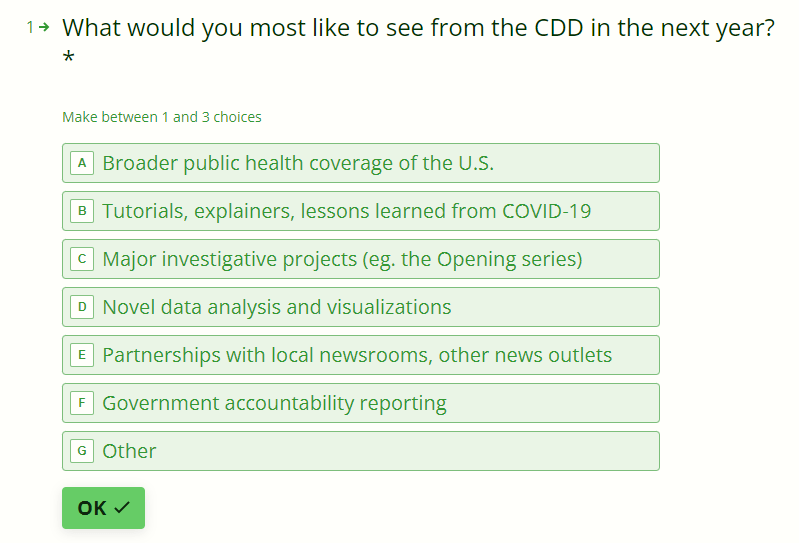

Survey: Looking forward to 2022

I recently wrapped up a big project over here at the COVID-19 Data Dispatch. (In case you missed it: I profiled five school communities that had successful reopenings in 2020-2021. Check out the project here!) Now that it’s done, I’ve been doing a bit of reflecting on the next steps for this publication—specifically, what I’d like it to look like one year from now.

My mission here is to provide you, my readers, with the information you need to understand what’s going on with COVID-19 in your community. I’m committed to covering the pandemic, for as long as it remains the number one health and science story in America.

But what happens when COVID-19 is no longer the number one health and science story in America? I started to consider this question early in summer 2021, before Delta came roaring in—and made many people realize that we were still pretty far away from the “end of the pandemic.” Delta allowed me to procrastinate, basically. But this is the kind of question one can only put off for so long, so here I am, considering it again.

As I think about the COVID-19 Data Dispatch’s future, I’m thinking about everything that this country needs to do in preparation for the next public health crisis. Because there will be a next public health crisis—in fact, climate change is already producing a never-ending stream of crises all around us. What information do we need, and what data-driven stories can we tell, to get ready? How can I serve my fellow journalists, scientists, health experts, and the other people in my community?

To help me figure this out, I’ve put together a survey for you, dear readers! It should be easy to fill out: 10 questions, mostly multiple choice. It can be done on a computer or a phone, and shouldn’t take you more than five minutes.

//embed.typeform.com/next/embed.jsIf the widget above doesn’t load, go to this link to fill out the survey: https://form.typeform.com/to/YOlZ2zB4

-

National numbers, September 26

California dropped to “substantial” transmission this week, while other states remained in “high” transmission. In the past week (September 18 through 24), the U.S. reported about 850,000 new cases, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 122,000 new cases each day

- 259 total new cases for every 100,000 Americans

- 17% fewer new cases than last week (September 11-17)

Last week, America also saw:

- 67,000 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals (21 for every 100,000 people)

- 11,000 new COVID-19 deaths (3.3 for every 100,000 people)

- 99% of new cases are Delta-caused (as of September 18)

- An average of 700,000 vaccinations per day (per Bloomberg)

Following the Labor Day reporting blips of the past two weeks, COVID-19 cases are now clearly trending down in the U.S. The daily new case average is close to what we saw in early August, at the start of the Delta surge.

The U.S. can’t let its guard down yet, though. Almost every state still reported over 100 new cases for every 100,000 people in the past week, putting the vast majority of the country into a high coronavirus transmission zone, per the CDC’s categories. The only state to drop below this “high transmission” threshold is California, which reported 86 new cases per 100,000 in the week ending September 23.

Alaska, West Virginia, Wyoming, and Montana are all far past that “high transmission” threshold, at over 600 new cases per 100,000 in the past week. Alaska appears to be the nation’s newest Delta hotspot. The state reported a record 1,735 COVID-19 cases on Friday, though some of those cases were part of a reporting backlog (meaning they occurred earlier).

Nationwide, hospitalizations are also continuing to come down. The country recorded fewer than 10,000 new patients a day last week, for the first time since early August. But the current numbers are still far higher than what we saw in June and early July.

Deaths—the slowest-moving pandemic metric—continue rising, with about 11,000 new deaths a day. It bears repeating: the vast majority of these deaths occur in unvaccinated Americans. The U.S. has now passed 675,000 deaths, meaning that COVID-19 has killed more Americans than the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic did over a century ago.

Despite the continued dangers of being unvaccinated, dose numbers are now also dropping in the U.S. After a couple of weeks approaching one million doses a day, we’re now back down at 700,000 doses a day, per Bloomberg’s dashboard. And the upcoming booster shot rollout is certain to confuse these data; already, 2.4 million Americans have received an additional dose, per the CDC.

-

COVID source shout-out: Teen vaccinations in Maine

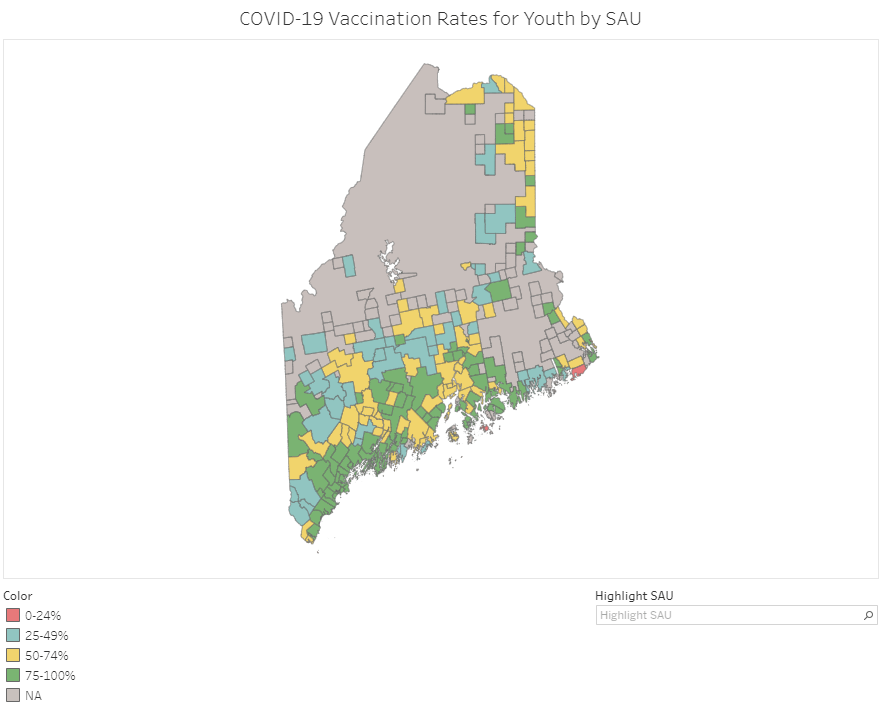

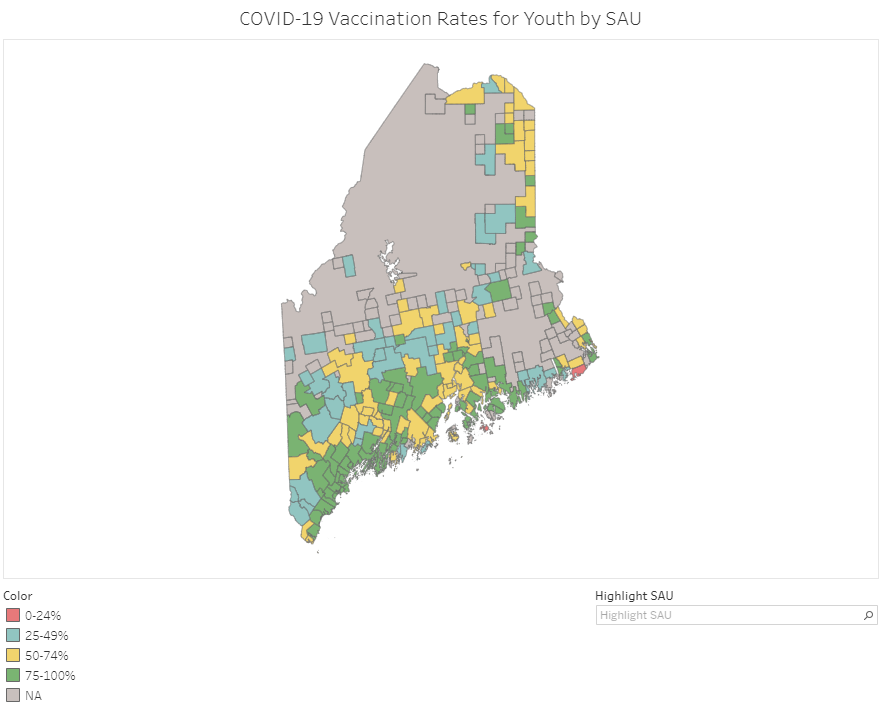

Vaccination rates in Maine’s school administrative units (SAUs). Screenshot taken on September 18. At this point in America’s vaccine rollout, almost every state has a detailed dashboard. (Nebraska and Florida used to have detailed dashboards, before taking those sites down earlier this summer in a growing trend of states reducing their COVID-19 reporting.)

Most states report vaccination rates by county, ZIP code, or another similar local jurisdiction. But when I was updating the COVID-19 Data Dispatch vaccine annotations page last week, I noticed one unique offering: Maine is reporting vaccination rates for teenagers, ages 12 to 18, by school administrative unit. School administrative units roughly correspond to school districts, though different parts of Maine have different school governance structures.

This dashboard is incredibly useful; individual school districts can compare their vaccination rates to those of their neighbors, while anyone doing state-level research can get a quick overview of where districts stand. As of September 18, just two districts have under 25% of their teens vaccinated (Cutler Public Schools and MSAD 76), while a few districts have vaccination rates over 95%.

Maine’s Division of Disease Surveillance intends to update these data “about every two weeks,” according to the agency’s website.