Last week, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine for children ages 5 to 11, under an Emergency Use Authorization. The agency’s vaccine advisory committee met on Tuesday to discuss Pfizer’s application and voted overwhelmingly in favor; the FDA followed this up with an EUA announcement on Friday.

This coming week, the process continues: CDC’s own vaccine advisory committee will discuss and vote on vaccinating kids in the 5-11 age group, and then the agency will make an official decision. If all goes well—and all is expected to go well—younger kids will be able to get their vaccines in time for Thanksgiving.

Many of the parents I know have been eagerly awaiting this authorization, but the sentiment is far from universal. COVID-19 vaccinations for kids are incredibly controversial, more so than vaccinations for adults. The public comment section of the FDA advisory committee meeting—in which basically anyone can apply to share their thoughts—was full of anti-vaxxers, many of them sharing misinformation. Even some experts on the FDA advisory committee were not fully convinced that vaccines are needed for all young kids, though all but one eventually voted in favor.

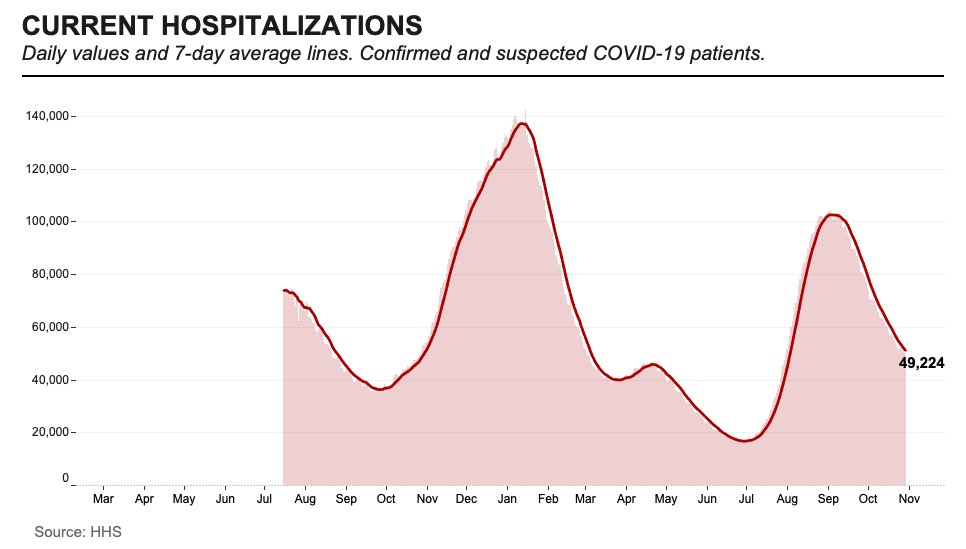

Now, let me be clear: there are definite benefits to vaccinating younger children. While kids are less likely to have severe COVID-19 cases than adults, the disease has still been devastating for many children. Almost 100 kids in the 5 to 11 age range have died of COVID-19, making this disease one of the top 10 causes of death for this group over the past year and a half.

Plus, children who get infected with the coronavirus are at risk for Long COVID and MIS-C, two conditions with long-lasting ramifications. There have been about 5,200 MIS-C cases thus far—and the majority of these cases have occurred in Black and Hispanic/Latino children. Minority children are also at much higher risk for COVID-19 hospitalization.

Vaccination can prevent children from severe ramifications of a potential COVID-19 case, as well as from the mild infections that lead to missed school and other disruptions. But the FDA committee had to carefully weigh this benefit against potential side effects from vaccination, namely myocarditis—a type of heart inflammation.

The U.S. system for tracking vaccine side effects has identified a small number of myocarditis cases in children ages 12 to 15 after their second shots of Pfizer or Moderna vaccines. For the meeting this past Tuesday, the FDA presented some models weighing potential myocarditis cases in young kids against vaccination benefits; the models showed that, in almost every scenario, the number of severe COVID-19 cases prevented by vaccination is higher than the myocarditis cases.

It’s worth noting: in Pfizer’s clinical trial for the 5 to 11 age group, no child had a severe adverse reaction to the vaccine. But the Pfizer researchers did observe five medical events that were unrelated to vaccination—including one kid who swallowed a penny.

Some of the FDA advisory committee members suggested that perhaps vaccines would be most beneficial for children with underlying medical conditions, who are more susceptible to severe COVID-19. But the committee ultimately voted in favor of vaccines for all kids in the 5 to 11 age group, allowing parents to consult their pediatricians and pursue vaccination if they deem it necessary.

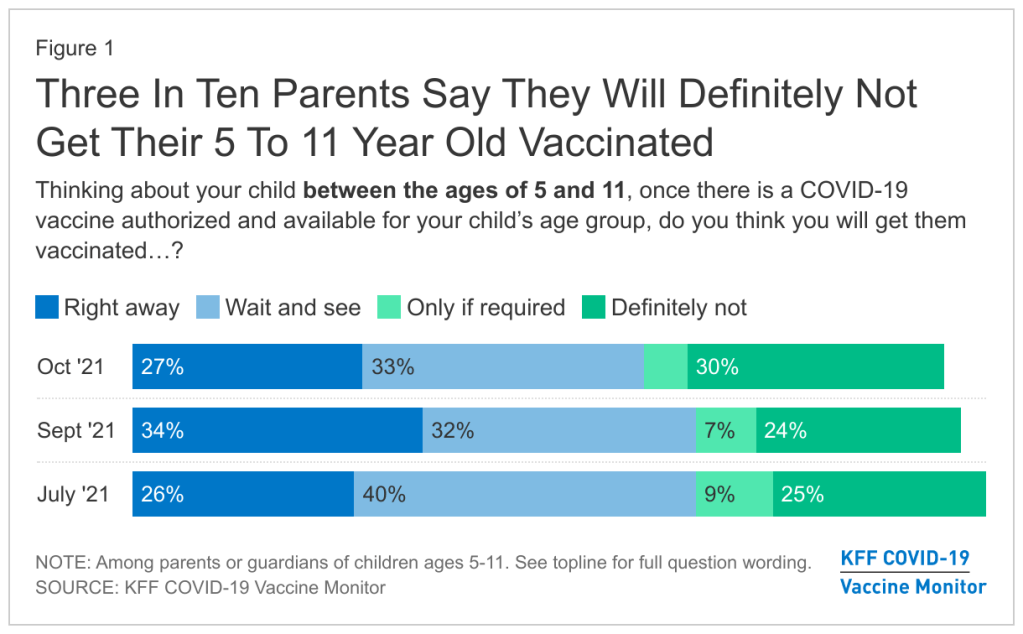

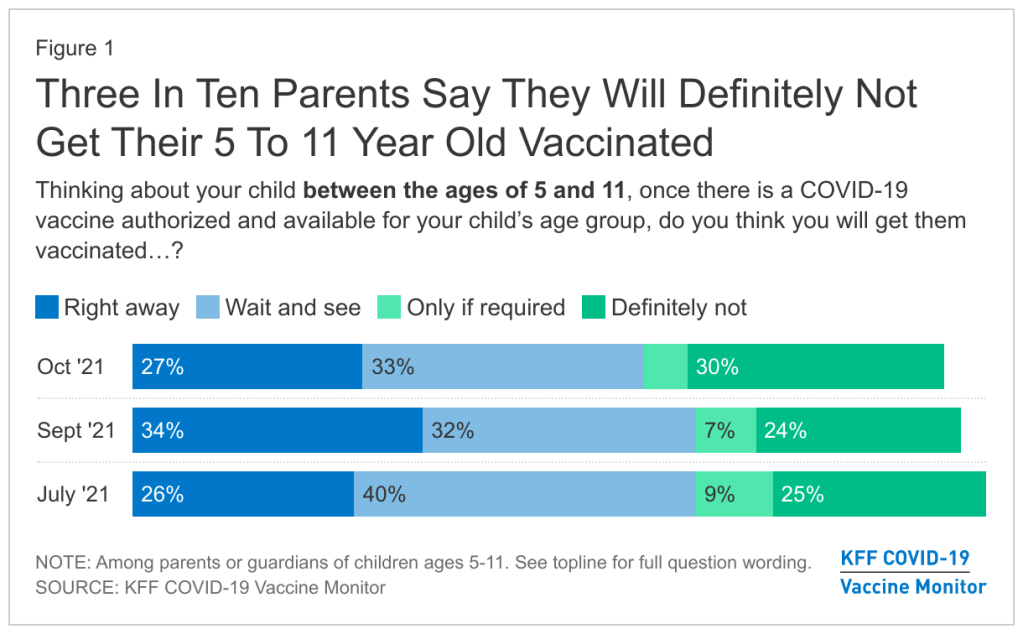

Polling data suggest that many parents don’t currently deem it necessary, though. The latest survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that just 27% of parents with kids in the 5 to 11 age range plan to get their kids vaccinated immediately, once shots are available. 33% intend to “wait and see,” 5% will only pursue vaccination if it’s required by the child’s school, and 30% say “definitely not.”

Public health experts, pediatricians, and others in the science communication world have a lot of work ahead of us to convey the importance of vaccinating kids—and dispel misinformation.

Note: this post relies heavily on STAT News’s liveblog of the FDA committee meeting.