- COVID Behaviors Dashboard from Johns Hopkins: John Hopkins University maintains one of the oldest and best-known COVID-19 dashboards of the pandemic. The team recently expanded its data offerings with a new dashboard focused on pandemic attitudes and practices around the world. This dashboard draws from surveys conducted in over 100 countries, in collaboration with the WHO; read more about it here.

- COVID-19 K-12 School Testing Impact Estimator: What COVID-19 testing strategy would make the most sense for your local K-12 school? This dashboard, by the Rockefeller Foundation and Mathematica (the data research organization), is designed to help stakeholders find out. Simply plug in the school’s characteristics and COVID-19 safety goals, and the dashboard will tell you how different testing strategies may measure up.

- Vaccine hesitancy roundup from the Journalist’s Resource: This resource page includes a wealth of data and insights on vaccine hesitancy in the U.S., drawing from a variety of surveys and research papers on the topic. As of early September, author Naseem Miller writes, the PubMed research database included over 750 studies on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, signifying growing academic interest in this topic.

- Hospital challenges to public health reporting: A new report from the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology explores the challenges that non-government hospitals have faced in electronically exchanging information with public health agencies. One major finding: in both 2018 and 2019, half of all hospitals lacked the capacity for this data exchange. No wonder electronic reporting has been such a challenge during the pandemic.

- NIH Long COVID initiative revs up: This isn’t an actual data source, more of an update: the National Institutes of Health (NIH)’s RECOVER Initiative to study Long COVID awarded a major research grant this week. About $470 million goes to New York University’s Langone Medical Center, which will serve as a national hub for Long COVID research and award sub-grants to other institutions. The NIH’s RECOVER website currently reports that between 10% and 30% of people infected with the coronavirus will go on to develop Long COVID; hopefully research at NYU and elsewhere will lead to some more precise numbers.

Blog

-

Featured sources, September 19

-

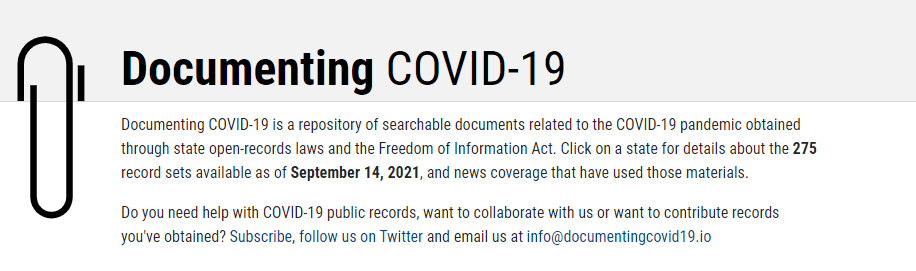

Betsy news: I’m joining Documenting COVID-19

Starting this week, I’m joining the team at Documenting COVID-19 on a part-time basis. Documenting COVID-19, for those unfamiliar, is an open-records project that makes pandemic data and records from all levels of the U.S. government available to journalists and researchers.

Project researchers also help journalists craft stories around these government records, contributing to investigative articles on topics ranging from death certificates to contact tracing challenges.

Documenting COVID-19 is run out of the Brown Institute for Media Innovation, a research institute run by Columbia and Stanford Universities; it’s been funded by the public records site MuckRock and other supporters.

The project is currently expanding to collect even more COVID-related documents and data, and I’m excited to be part of that expansion! I look forward to unearthing stories, collaborating with local newsrooms, developing my investigative skills, and generally working to hold U.S. institutions accountable for their pandemic failures.

And, for any local reporters reading this, if you have a story idea or project where you could use some assistance from Documenting COVID-19, let me know! (Email me, hit me up on Twitter, etc.)

-

Boosters for the vulnerable: FAQs following the FDA advisory meeting

This past Friday, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s vaccine advisory committee voted to recommend booster shots of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for all Americans over age 65 and those who are particularly vulnerable to the virus, due to their health conditions and/or work environments. This was a notable recommendation because it went against the FDA’s ask: booster shots for everyone over the age of 16.

Let’s walk through the data behind this decision.

How is the current two-dose vaccine regimen faring against severe COVID-19 disease?

Before we get into any numbers, it’s important to remember the initial goal of the COVID-19 vaccines: protect people against severe disease, hospitalization, and death, basically reducing the coronavirus’ power to cause deadly harm.

On this front, all of the vaccines are performing well. Numerous papers cited during the advisory meeting, as well as the U.S.’s breakthrough case data, suggest that vaccination protects against severe COVID-19 disease for the vast majority of recipients. Among over 178 million people who had been fully vaccinated in the U.S. by mid-September, just 3,000 have died following a positive COVID-19 test. Those 3,000 deaths account for just about 1% of all COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. since January 2021.

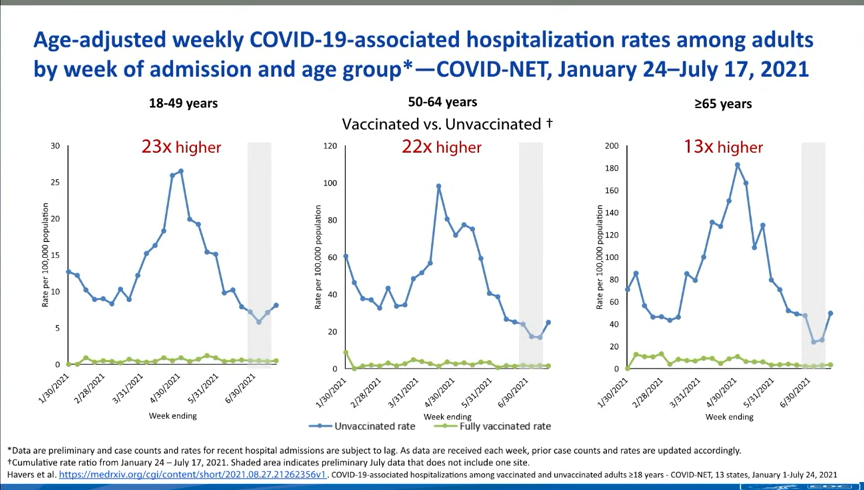

The numbers get a bit more complex, however, when you look at older adults and other vulnerable populations. Those who were more vulnerable to a severe COVID-19 case in the first place are also more vulnerable to having a severe breakthrough case, if they encounter the virus after vaccination. One chart, presented at the FDA meeting, provides a picture of this trend. From late January to mid-July, 2021, the hospitalization rate among younger adults (ages 18-49) was 23 times higher for the unvaccinated than for the vaccinated. For seniors (over age 65), however, the rate was 13 times higher for the unvaccinated.

Seniors are more likely to experience a severe breakthrough case than younger adults, CDC data suggest. How is that current regimen faring against coronavirus infection?

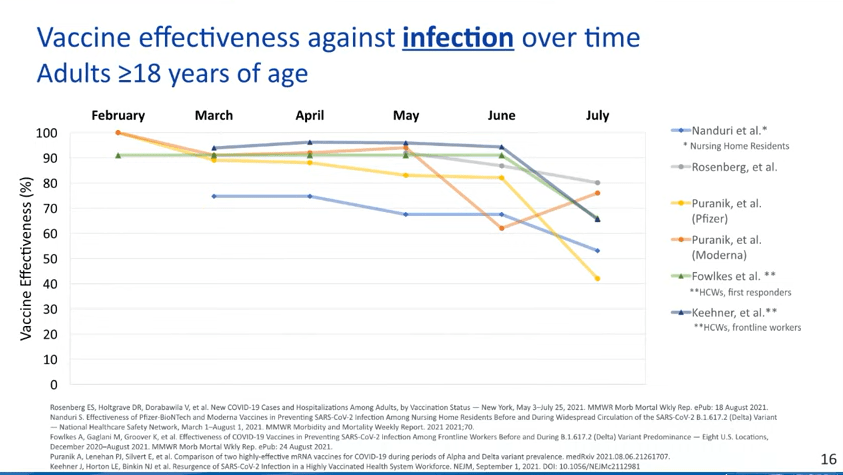

This is where we see a bigger drop in efficacy. Multiple studies point to the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines becoming less capable of protecting recipients against infection, over time; in other words, if you got your two shots in April 2021, you’re more likely to get a positive test result now, in September, than you were in May. (Though your case will likely be mild or asymptomatic!)

While the vaccines are still highly effective against severe disease, their effectiveness against coronavirus infection appears to be waning. We can also see this in breakthrough case numbers when we look at all infections, as opposed to only those cases that lead to severe disease or death. This type of analysis is difficult to do in the U.S., as the CDC is only systematically tracking those severe cases, but we can see patterns in the data from local jurisdictions that are reporting their breakthrough cases more comprehensively.

For example, let’s look at Washington, DC, which reports breakthrough cases in extensive detail:

Washington, D.C. is seeing many more breakthrough cases now than it was earlier in 2021. During the week of March 8, DC reported 14 breakthrough cases. The district reported about 800 cases overall that week, meaning that breakthroughs accounted for 2% of all cases.

During the week of August 23, however, the district reported almost 500 breakthrough cases. In that week, the district reported about 1,400 cases overall—meaning that breakthrough cases have jumped from 2% of all weekly DC cases to 35% of all weekly DC cases.

DC also reports a breakdown of breakthrough cases according to the time it’s been since residents were fully vaccinated. This reveals that most breakthroughs occur at least two months after an individual completed their dose series, with the highest number of breakthroughs in people who’d been vaccinated three to four months ago. We can assume that similar patterns are occurring elsewhere in the country.

It’s also worth noting that we don’t have a great sense of how well the vaccines protect against Long COVID—though data thus far suggest that post-vaccination Long COVID cases are much rarer than non-breakthrough cases.

Why are the vaccines appearing to lose their effectiveness?

This was a big point of discussion for the FDA advisory committee. Are the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines appearing to lose their ability to protect us against coronavirus infection because Delta has a special ability to evade the vaccines or because the vaccines become less effective over time?

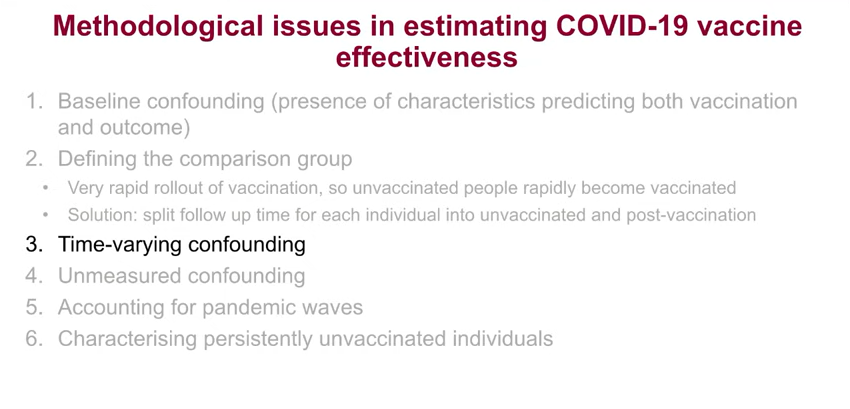

One early-morning presenter at the FDA meeting, medical statistician Jonathan Sterne from the University of Bristol, dove into this issue. His presentation focused on confounders, a statistical term for an outside force that influences the question a researcher is trying to study. In the case of vaccine effectiveness, Sterne said, there are a lot of confounders; these include vaccine recipients’ ages, how long ago they were vaccinated, and when they were vaccinated (i.e. in which phase of the pandemic?).

Sterne’s presentation focused on the confounders that make it difficult to estimate vaccine effectiveness. Sterne and other British researchers have taken advantage of the U.K.’s extensive electronic health records to analyze how well the vaccines are working, attempting to take these confounders into consideration. Overall, he said, it’s very challenging to get trustworthy effectiveness numbers—though the U.K. has approved boosters for residents over age 50, so it’s clear that the country’s public health agency does see some need for the additional shots.

Sterne’s presentation, as did a presentation from Israeli public health officials, also underscored the need for the U.S. to collect more standardized data on breakthrough cases, among other things.

Why did the FDA advisory committee vote against booster shots for everyone, ages 16 and over?

When this advisory committee votes on a question regarding vaccines or another biological product, the committee is specifically asked to consider whether the benefits of the product outweigh the risks. In this case, do the benefits of widespread boosters outweigh the risks of potential side effects from those additional doses?

When it comes to those risks of potential side effects, the committee had strikingly little data to evaluate. Pfizer did conduct a clinical trial of booster shots, but it only included 306 participants—an incredibly small number, when compared to the massive trials of the vaccine’s original two-dose regimen. The trial didn’t include any participants under age 18 or over age 55, which some advisory committee members found problematic, as they were being asked to consider approval for all Americans over age 16.

Israel—which has now administered booster shots to over 2.8 million residents—provided some data on side effects, but their utility is limited. The country started giving boosters to older adults before moving to younger adults, limiting Israeli health officials’ ability to identify potential risk for myocarditis or other severe side effects that might be more common in the younger population.

Israel has only identified 19 serious vaccine side effects from its booster shot rollout thus far, but the majority of the country’s young adults have yet to be vaccinated. While data from Israel do suggest that booster shots can bring down infection numbers in an overall population, the FDA advisory committee did not find that a sufficient argument to recommend boosters for all Americans. Not at this time, anyway.

Why did the committee vote to support boosters for seniors and other vulnerable populations?

The risks of booster shots may not be clear for younger adults, but the risks of a breakthrough COVID-19 case are clear for older adults and others with health conditions that make them more vulnerable to severe COVID-19 case. The committee’s vote to recommend boosters for vulnerable groups aligns with a growing scientific consensus: that the U.S. should protect seniors, nursing home residents, and others who are at higher risk for serious COVID-19 cases.

What happens next?

It’s important to underscore here that this booster shot recommendation came from a committee that advises the FDA, not from the FDA itself. The agency typically follows its committee’s recommendations, but it doesn’t have to. We can expect the FDA’s decision—approval of booster shots for vulnerable groups, for everyone over age 16, or something else—within a couple of days.

Next week, on Wednesday and Thursday, a CDC advisory committee is set to meet to further discuss booster shots. If both the FDA and CDC approve boosters, health departments across the country are prepared to begin administering them to eligible Americans; this will likely include seniors and other vulnerable adults who previously got two shots of the Pfizer vaccine.

What about everyone who got the Moderna or Johnson & Johnson vaccines?

Again, this decision focused on the Pfizer vaccine, so Moderna and J&J recipients will need to wait for more data and more deliberation. Moderna has formally applied to the FDA for authorization of its booster shot, so we may see a similar series of meetings about that vaccine in the coming weeks.

J&J vaccine recipients will likely experience a longer wait as researchers collect data on the effectiveness of this one-shot vaccine. CNET has a good explainer of the situation.

Also: If you’d like to read a more detailed breakdown of everything that happened at Friday’s advisory committee meeting, I highly recommend the STAT News liveblog by Helen Branswell and Matthew Herper, which I drew upon heavily in writing this post.

More vaccines reporting

-

Opening project conclusion: 11 lessons from the schools that safely reopened

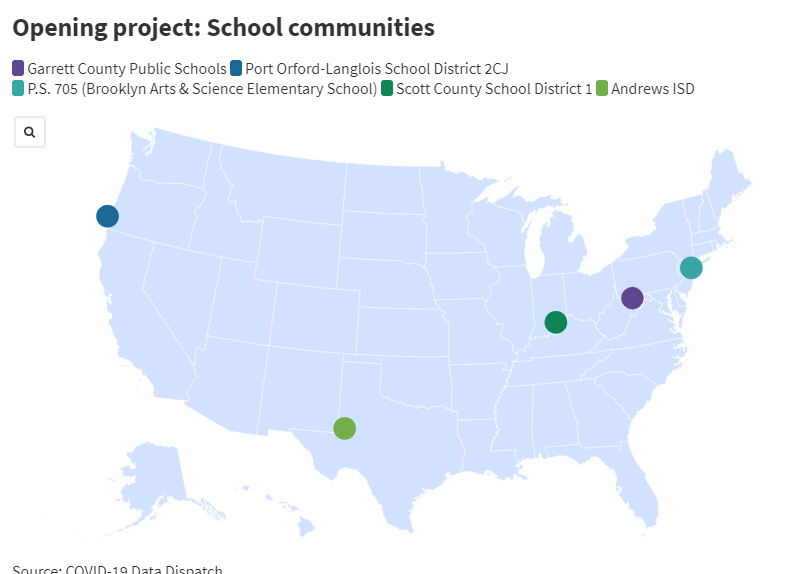

In the COVID-19 Data Dispatch’s “Opening” series, we profiled five school communities that successfully reopened during the 2020-2021 school year. In each one, the majority of the district’s or school’s students returned to in-person learning by the end of the spring semester — and officials identified COVID-19 cases in under 5% of the student population.

Through exploring these success stories, we found that the schools used many similar strategies to build trust with their communities and keep COVID-19 case numbers down.

These are the five communities we profiled:

- Scott County School District 1 in Austin, Indiana: This small district faced a major HIV/AIDS outbreak in 2015, leading to an open line of communication between Austin’s county public health agency, school administrators, and other local leaders which fostered an environment of collaboration and trust during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Garrett County Public Schools in Maryland: In a rural, geographically spaced-out county, this district built trust with its community by utilizing local partnerships, providing families with crucial supplies, setting up task forces to plan reopening, and communicating extensively with parents.

- Andrews Independent School District in Texas: This West Texas district prioritized personal responsibility, giving families information to make individual choices about their children’s safety. Outdoor classes and other measures also helped keep cases down.

- Port Orford-Langlois School District 2CJ in Oregon: In two tiny towns on the coast of Oregon, this district built up community trust and used a cautious, step-by-step reopening strategy to make it through the 2020-2021 school year with zero cases identified in school buildings.

- P.S. 705 in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, New York: This elementary school brought 55% of students back to in-person class, well above the New York City average (40%), by utilizing comprehensive parent communication and surveillance testing of students and staff.

Here are 11 major lessons we identified from the districts that kept their communities safe.

1. Collaboration with the public health department is key.

In Austin, Indiana, an existing relationship between the local school district and local public health department, built during the town’s HIV/AIDS outbreak in 2015, streamlined COVID-19 communication. The district and public health department worked together to plan school reopening, while district residents — already familiar with the health department’s HIV prevention efforts — quickly got on board with COVID-19 safety protocols.

Garrett County’s school district, in Maryland, worked with their local public health department on making tests available to students and staff. The Andrews County district, in Texas, also collaborated with the county health agency on testing and on identifying student cases in fall 2020 — though the relationship fractured later in the school year due to differing opinions on the level of safety measures required in schools.

“What the CDC basically said is that each school has to become a little health department in its own right,” said Katelyn Jetelina, epidemiologist at the University of Texas and author of the Your Local Epidemiologist newsletter; but “schools don’t have the expertise to do that,” she said. As a result, public health departments themselves may be valuable sources of scientific knowledge for school leaders.

“What’s ideal — and I’ve only seen this happen a few times — is, if there is literally someone from the health department embedded in the school district,” added Robin Cogan, legislative co-chair for the New Jersey State School Nurses Association and author of the Relentless School Nurse blog.

2. Community partnerships can fill gaps in school services.

In addition to public health departments, there are other areas where partnerships outside a school may be beneficial; partnering up to address technology and space needs was a particular theme in this project. In Oregon, the Port Orford-Langlois school district relied on the local public library to provide technology services, space for after-school homework help, wifi outside school hours, and even extracurricular activities. Meanwhile, in Garrett County, Maryland, the school district worked with churches, community centers, and other centrally-located institutions to provide both wifi and food to district families.

Both of these rural districts faced challenges with online learning, as many families did not have wifi at home. By expanding internet access through community partnerships, the districts enabled families to keep up kids’ online learning — while showing parents that school staff were capable of meeting their needs, building trust for future in-person semesters.

3. Communication with parents should be preemptive and constant.

Strong communication was one theme that resonated across all five profiles. In a tumultuous pandemic school year, parents wanted to know exactly what their schools were doing and why; the districts we profiled offered ample opportunities for parents to quickly get updates and ask questions.

For example, at Brooklyn’s P.S. 705, administrators held weekly town hall meetings — segmented by grade level — and staffed a “virtual open office,” available on a daily basis for parents to log on and ask questions. Jetelina said that such forums are an ideal opportunity for “two-way communication,” in which administrators could both talk to parents and listen to feedback.

Andrews County also held a town hall for parent questions prior to the start of the 2020 school year. In Garrett County, administrators updated a massive FAQ document (currently 22 pages) whenever a parent reached out with a question. This district, P.S. 705, and Port Orford-Langlois all gave parents the opportunity to talk to school staff in one-on-one phone calls.

Cogan pointed out that parents like to be reached on different platforms, such as text messages, Facebook, and Google classroom; by giving parents multiple options, districts may ensure that all parent questions are asked and answered.

4. Require masks, and model good masking for kids.

Mask requirements in schools have become highly controversial in fall 2021, with some parents enthusiastically supporting them while others refuse to send their children to school with any face covering. But widespread masking remains one of the best protections against COVID-19 spread, especially for children who are too young to be vaccinated.

And yes, evidence shows that young children can get used to wearing a mask all day. In the Port Orford-Langlois school district, Principal Krista Nieraeth credits responsible masking among students to their parents. Though the community leans conservative, she said, parents modeled mask-wearing for their kids, understanding the importance of masking up to prevent the coronavirus from spreading at school. Some parents even donated homemade masks to the district for students and teachers.

As Delta spreads, Cogan said, it’s important that districts require “properly fitting masks that are worn correctly” to ensure that students are fully protected.

5. Regular testing can prevent cases from turning into outbreaks.

Brooklyn’s P.S. 705 leaned into the surveillance COVID-19 testing program organized by the New York City Department of Education. The city required schools to test 20% of on-site students and staff once a week, from December 2020 through the end of the spring semester; P.S. 705 tested far above this requirement during the winter months, when cases were high in Brooklyn. The testing allowed this school to identify cases among asymptomatic students, quarantine classes, and stop those isolated cases from turning into outbreaks.

School COVID-19 testing programs should test students frequently, Jetelina said. “But what’s even more important than regular testing is it’s not biased testing,” meaning the tests are required for all in-person students. Voluntary testing, she said, would be more likely to include only the families who are also more likely to follow other safety protocols.

More districts are now working to set up regular testing programs for fall 2021, using funding from the American Rescue Plan, Cogan said. If regular testing isn’t possible, it’s still crucial for a district to make tests easily available — with timely results, in under 24 hours — to a student’s close contacts when a case is identified at school. Both the Garrett County and Andrews County school districts worked with their local public health departments to make such testing possible.

6. Improve ventilation and hold classes outside where possible.

In addition to funding for COVID-19 testing, the American Rescue Plan made billions of dollars available for improvements to school ventilation systems. The Garrett County and Austin, Indiana school districts both took advantage of this funding to upgrade HVAC systems in their buildings and buy portable air filtration units.

In Andrews County — where the West Texas weather stays warm through much of the year — the school district opted for more natural ventilation: opening doors and windows, and holding class outside whenever possible. The extra time outdoors was also beneficial to the mental health of students who had been cooped up indoors in spring 2020, administrators said.

Still, outdoor class may not be possible for districts in urban areas, Cogan said. In these schools, windows and doors may be locked down to protect against a different public health crisis: the threat of gun violence.

7. Schools may still be focusing too much on cleaning.

In July 2020, Derek Thompson, staff writer at The Atlantic, coined the term “hygiene theater”: many businesses and public institutions were devoting time and resources to deep-cleaning — even though numerous scientific studies had demonstrated that the virus primarily spreads through the air, not through surface contact.

More than a year later, hygiene theater is alive and well in many school districts, COVID-19 Data Dispatch interviews with school administrators revealed. When we asked in interviews, “What were your safety protocols?”, administrators often jumped to deep-cleaning and bulk hand sanitizers. Ventilation would come up later, after additional questioning. At the Andrews County district, for example, custodians would clean a classroom once a case was identified — but close contacts of the infected student were not required to quarantine.

“Cleaning high-touch areas is very important in schools,” Cogan said. But mask-wearing, physical distancing, vaccinations, and other measures are “higher protective factors.”

8. Give agency to parents and teachers in protecting their kids.

Last school year, many districts used temperature checks and symptom screenings as an attempt to catch infected students before they gave the coronavirus to others. But in Austin, Indiana, such formalized screenings proved less useful than teachers’ and parents’ intuition. Instructors could identify when a student wasn’t feeling well and ask them to go see the nurse, even if that student passed a temperature check.

Jetelina said that teachers and parents can both act as a layer of protection, stopping a sick child from entering the classroom. “Parents are pretty good at understanding the symptoms of their kids and the health of their kids,” she said.

In Andrews, Texas, district administrators provided parents with information on COVID-19 symptoms and entrusted those parents to determine when a child may need to stay home from school. The Texas district may have “gone way overboard with giving parents agency,” though, Cogan said, in allowing students to opt out of quarantines and mask-wearing — echoing concerns from the Andrews County public health department.

9. We need more granular data to drive school policies.

The COVID-19 Data Dispatch has consistently called out a lack of detailed public data on COVID-19 cases in schools. The federal government still does not provide such data, and most states offer scattered numbers that don’t provide crucial context for cases (such as in-person enrollment or testing figures). Without these numbers, it is difficult to compare school districts and identify success stories.

The “Opening” project also illuminated another data issue: Most states are not providing any COVID-19 metrics down to the individual district, making it hard for school leaders to know when they must tighten down on or loosen safety protocols. At the tiny Port Orford-Langlois district in Oregon, for example, administrators had to rely on COVID-19 numbers for their overall county. Even though the district had zero cases in fall 2020, it wasn’t able to bring older students back in person until the spring because outbreaks in another part of the county drove up case numbers. Cogan has observed similar issues in New Jersey.

At a local level, school districts may work with their local public health departments to get the data they need for more informed decision-making, Jetelina said. But at a larger, systemic level, getting granular COVID-19 data is more difficult — a job for the federal government.

10. Invest in school staff and invite their contributions to safety strategies.

School staff who spoke to the COVID-19 Data Dispatch for this project described working long hours, familiarizing themselves with the science of COVID-19, and exercising immense determination and creativity to provide their students with a decent school experience. Teaching is typically a challenging job, but in the last eighteen months, it has become heroic — even though many people outside school environments take this work for granted, Jetelina said.

Districts can thank their staff by giving them a say in school safety decisions, Cogan recommended. “Educators, they’ve had a God-awful time and had a lot more put on them,” she said. But “every single person that works in a school has as well.” That includes custodians, cafeteria workers, and — crucially — school nurses, who Cogan calls the “chief wellness officer” of the school.

11. Allow students and staff the space to process pandemic hardship.

About 117,000 children in the U.S. have lost one or both parents during the pandemic, according to research from Imperial College London. Thousands more have lost other relatives, mentors, and friends — while millions of children have faced job loss in their families, food and housing insecurity, and other hardships. Even if a school district has all the right safety logistics, school staff cannot truly support students unless they allow time and space to process the trauma that they’ve faced.

P.S. 705 in Brooklyn may serve as a model for this practice. School staff preemptively reached out to families when a student missed class, offering support. “705 is just the kind-of place where it is a ‘wrap your arms around the whole family’ kind-of a school,” one parent said.

On the first day of school in September 2021 — when many students returned in-person for the first time since spring 2020 — the school held a moment of silence for loved ones that the school community has lost.

These lessons are drawn from school communities that were successful in the 2020-2021 school year, before the Delta variant hit the U.S. This highly-transmissible strain of the virus poses new challenges for the fall 2021 semester. The data analysis underlying this project primarily led us to profile rural communities, which may have gotten lucky with low COVID-19 case numbers in previous phases of the pandemic — but are now unable to escape Delta. For example, the Oregon county including Port Orford and Langlois saw its highest case rates yet in August 2021.

The Delta challenge is multiplied by increasing polarization over masks, vaccines, and other safety measures. Still, Jetelina pointed out that there are also “a ton of champions out there,” referring to parents, teachers, public health experts, and others who continue to learn from past school reopening experiences — and advocate for their communities to do a better job.

Have you taken lessons from the “Opening” project to your local school district? Do you see parallels between the five communities in this project and your own? If so, we would love to hear from you. Comment below or email betsy@coviddatadispatch.com.

The COVID-19 Data Dispatch’s “Opening” series is available for other publications to republish, free of charge.

More from the Opening series

-

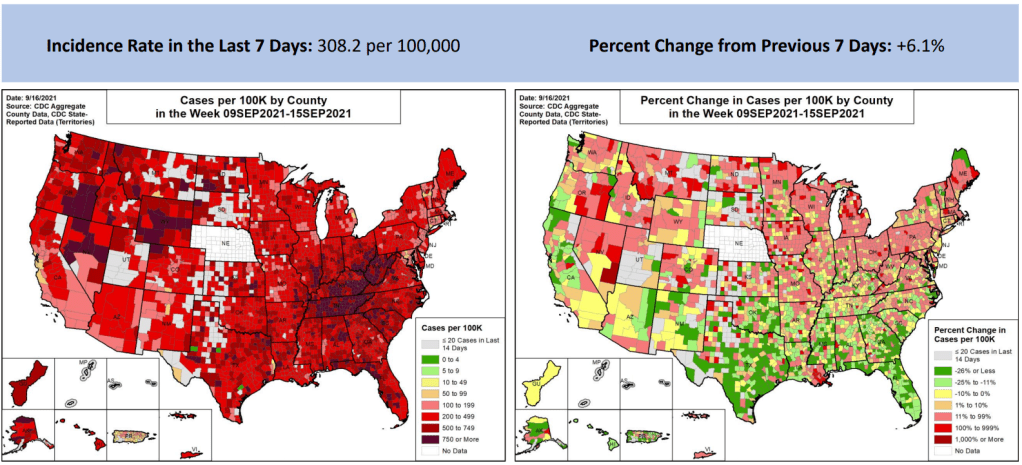

National numbers, September 19

Some previous Delta hotspots are seeing case numbers decrease, while others are now seeing their highest cases yet. Charts from the September 16 Community Profile Report. In the past week (September 11 through 17), the U.S. reported about one million new cases, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 146,000 new cases each day

- 312 total new cases for every 100,000 Americans

- 6% more new cases than last week (September 4-10)

Last week, America also saw:

- 78,000 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals (24 for every 100,000 people)

- 10,000 new COVID-19 deaths (3.1 for every 100,000 people)

- 100% of new cases now Delta-caused (as of September 11)

- An average of 800,000 vaccinations per day (per Bloomberg)

Last week, national case numbers appeared to be in a decline, with a 13% decrease from the prior week. This week, cases bumped back up slightly—most likely due to delayed reporting driven by the Labor Day weekend, as I predicted in last week’s issue.

Still, this week’s daily new case average is lower than it was a couple of weeks ago. And the number of COVID-19 patients newly admitted to hospitals, a crucial metric that’s less susceptible to holiday reporting interruptions, has continued to drop: from about 12,000 new patients a day last week to 11,000 new patients a day this week.

But we can’t say the same thing for death numbers, unfortunately. Over 10,000 COVID-19 deaths were reported in the U.S. last week, the highest number since March 2021 (at the tail end of the winter surge.)

The country reached a sad milestone this week: one in 500 Americans have died of COVID-19, according to a Washington Post analysis. For Black, Hispanic, and Native Americans, as well as states that have been harder-hit by the pandemic, that number is lower. In Brooklyn, where I live, COVID-19 has killed one in every 240 residents.

In some parts of the country, the Delta surge appears to be letting up. Florida saw an 18% decrease in cases from last week to this week, according to the September 16 Community Profile Report, while Texas saw an 8% decrease. California—where residents just voted to keep harsh-on-COVID-19 Governor Gavin Newsom in power—saw a whopping 23% decrease in cases, week over week.

Meanwhile, other parts of the South and West are seeing their highest case numbers yet. Both Tennessee and West Virginia have recorded over 700 new cases for every 100,000 residents in the past week. (For context: the CDC says that over 100 new cases per 100,000 constitutes high transmission.) In West Virginia, hospitals are “overwhelmingly inundated” with COVID-19 patients. And in Alabama, though case numbers are coming down, a whopping 50% of hospital ICU patients have COVID-19.

According to the latest CDC variant estimates, 99.7% of new cases in the country are now caused by Delta. Delta has been causing over 99% of cases for a few weeks now. Has the variant run its course here? Could it mutate into something even more transmissible, or more deadly? Or is the CDC even collecting data comprehensively enough for us to tell? Many different scenarios seem plausible as we head into the colder months.

-

Featured sources, September 12

- K-12 Education Polls: Staff at EdChoice, a nonprofit education research organization, are keeping track of polling on school reopening and various related safety strategies, such as vaccine and mask requirements. This spreadsheet includes over 300 polls going back to March 2020.

- The Overlooked, K-12 report: Here’s another K-12 reopening source: a new report from the education-focused Walton Family Foundation characterizing families who felt dissatisfied by their education choices in fall 2020. The report includes estimates of students who changed schools, failed to enroll in formal schooling, or otherwise “are frustrated with their current schooling option and lack access to their preferred alternative(s).”

- Case and death underreporting in nursing homes: In a new paper published this week, researchers from Harvard University estimated that over 68,000 COVID-19 cases and over 16,000 deaths among U.S. nursing home residents have gone unreported in federal data. The researchers made their facility-level underreporting estimates available on GitHub, including nursing homes in 20 states that were utilized for the analysis.

- Case acceleration by state: In July, STAT News data project manager J. Emory Parker introduced a new metric for visualizing the pandemic: case acceleration, or how fast cases are increasing (or decreasing). Now, you can view state-by-state case acceleration numbers in real-time on STAT’s website. The dashboard is updated daily with data from the CDC, Johns Hopkins, and Our World in Data.

-

Biden’s new COVID-19 plan excludes data

No mention of data reporting or infrastructure here. Screenshot taken from whitehouse.gov on September 12. On Thursday, President Joe Biden unveiled a major new plan to bring the U.S. out of the pandemic. If you missed the speech, you can read through the plan’s details online.

Key points include vaccination requirements for large employers, federal workers, and federal contractors; booster shots (if the FDA and CDC approve them); and making rapid tests more accessible for the average American. Much of the plan aligns with safety strategies that COVID-19 experts have been recommending for months—or, in the case of rapid testing access, over a year.

But I and other data nerd friends were quick to notice that one major topic is missing: data collection. Numerous reports and investigations have demonstrated how the U.S.’s underfunded state and local public health agencies were completely unprepared to collect and report COVID-19 metrics, hindering our response to the pandemic. (This POLITICO investigation is one recent example of such a story.) Local data collection has gotten even worse during the latest surge, as many states cut back on their COVID-19 reporting and the federal government has failed to comprehensively track breakthrough cases.

As a result, one might expect Biden’s plan to take steps towards improving COVID-19 data collection in the U.S. Perhaps the plan could have provided funding to local public health agencies, tied to a requirement that they report certain COVID-19 metrics on a daily basis. Perhaps it could have included increased tracking for breakthrough cases, or increased genomic sequencing to identify the next variant that inevitably becomes a concern after Delta.

Instead, the plan’s only mention of “data” is a line about how well the vaccines work: “recent data indicates there is only 1 confirmed positive case per 5,000 fully vaccinated Americans per week.”

Without prioritizing data, the Biden administration is failing to prepare the U.S.—both for future phases of this pandemic and for future public health crises.

-

Fall 2021 school reopening: Stats so far

Over 1,400 schools have closed temporarily thus far in fall 2021, according to data collected by Burbio. Screenshot taken on September 11. The COVID-19 Data Dispatch has, clearly, been pretty focused on school reopening in recent weeks. But our “Opening” project is primarily retrospective, looking back at schools that were successful last school year. This fall, the Delta variant and additional political pressures have made reopening success even harder to achieve.

With some schools now over a month into the fall semester—while others, like those in NYC, are finally starting class next week—let’s talk about how reopening has gone thus far.

Many schools in high-transmission areas have closed temporarily. “More than 1,400 schools across 278 districts in 35 states that began the academic year in person have closed,” writes U.S. News reporter Lauren Camera, citing data from the tracking organization Burbio. Due to out-of-control COVID-19 outbreaks, some districts switched temporarily to remote learning while others fully closed or delayed the start of class.

While that may seem striking, it’s just about 1.4% of the 98,000 public school districts in the U.S. And, as you can see from Burbio’s closure map, many of the districts that had to shut down are located in Southern states with limited COVID-19 safety protocols. In Texas, for example, over 70,000 K-12 students have tested positive for COVID-19 since the beginning of the fall semester, out of about 5.3 million total students. In the 2020-2021 school year, about 148,000 Texas students got COVID-19 in total. This is a pretty clear signifier of the increasing danger that Delta, combined with lower mask use in schools, may bring to classrooms.

The school districts that closed include Scott County School District 1, the subject of our first “Opening” profile. This Indiana district originally opened in August 2021 with no mask requirement; cases quickly climbed, leading the district to shift to virtual instruction for two weeks. When students returned to classrooms in late August, masks were required once again.

Schools with stricter COVID-19 precautions are faring better. Many of those school districts that start earlier in August are located in the South. From a news cycle perspective, that means we tend to hear about the schools that shut down due to outbreaks before we hear about the schools that aren’t seeing so much virus transmission.

For example: this past Thursday, San Francisco’s local health department announced that the city has not seen a single case of transmission at a public school. School started on August 17, giving officials about one month of data for the district’s over 50,000 students. Safety precautions in San Francisco schools include required masking, surveillance testing, ventilation updates, and mandatory vaccination for teachers and staff. Dr. Naveena Bobba, from the city public health department, additionally said that about 90% of residents in the 12 to 17 age group are fully vaccinated.

We’re starting to see vaccine mandates for students in addition to teachers and staff. Los Angeles Unified is now requiring vaccination for all eligible students, ages 12 and up. LA is the second-largest school district in the country, serving over 600,000 students—including 225,000 who are eligible for vaccination. The majority of those students are already vaccinated, according to the county public health department; the rest will have until October 31 to catch up.

LA’s school district follows many colleges and universities that have required vaccination and Culver City Unified, another California district that announced a student mandate in late August. As vaccination rates in the 12-17 age group tend to be low and parent hesitation tends to be high, student vaccination mandates likely won’t be as common as staff mandates. But I wouldn’t be surprised if we see more districts make this requirement.

Despite federal encouragement to provide regular COVID-19 testing, many schools aren’t doing it. The Biden administration “Path out of the Pandemic” plan focuses on COVID-19 testing, including a call for K-12 school districts to set up regular testing for unvaccinated students and staff. If all schools followed the CDC’s testing guidance, they’d be testing at least 10% of students, at least once a week. (This is, again, an area where many colleges and universities are already excelling.)

School districts have had months to tap into $10 billion set aside specifically for school testing in the American Rescue Plan. But many districts are still not testing, or are offering tests only to students who show COVID-19 symptoms or were recently in contact with a case. The nation’s largest school district (New York City) has even loosened its testing protocol from last year—shifting from mandatory testing for 20% of students and staff every week, to non-mandatory testing for 10% of unvaccinated students every other week. Some parents and staff are not happy about the change, saying that NYC should be testing more, not less.

The federal government is expanding school data collection, but still not counting cases. After Biden took office, the federal Department of Education started surveying schools on their pandemic protocols—asking whether schools were open online, in-person, or hybrid, how many students were choosing different options, and other similar questions. Survey data are made public on a federal dashboard, updated once a month; but the data are fairly incomplete, with numbers unavailable for about 20 states and all but ten individual districts.

Now, the federal DOE is expanding its survey efforts “by asking more questions about how students learn and what precautions schools take,” according to EdWeek. But if the DOE doesn’t also expand its survey to more school districts and states, it’s unclear how useful these data will be. And the federal government still isn’t tracking the most important metric here: actual case counts in schools!

While pediatric case counts soar, children are still at low risk for severe disease. As we see reports of record cases in children and overwhelmed pediatric ICUs, it is important to recognize that—tragic as these reports may be—the majority of kids who contract COVID-19 have mild cases.

An article from the German news site Spektrum der Wissenschaft, republished in Scientific American, helps to explain how children’s immune systems work to recognize the novel coronavirus and stop the virus from causing severe disease:

The immune system uses a special mechanism to protect children from novel viruses—and it typically saves them from a severe course of COVID-19 in two different ways. In the mucous membranes of their airways, it is much more active than that of adults. In children, this system reacts much faster to viruses that it has never encountered, such as pandemic pathogens. At least, that is what a recent study by Irina Lehmann of the Berlin Institute of Health at Charité and her colleagues suggests.

As children get older, the article explains, immune system resources are shifted from this innate response to a memory-based response; adults are thus more protected against viruses that they’ve encountered before.

Read the Opening series

-

Opening profile: Going above and beyond in Crown Heights, Brooklyn

A fouth-grade classroom at P.S. 705, set up with desks in small clusters, windows open, and improved mechanical ventilation for fall 2021. Photo taken by Betsy Ladyzhets (COVID-19 Data Dispatch). On the morning of Aug. 26, parents from Brooklyn Arts & Science Elementary School (or P.S. 705) flocked to the school for an open house ahead of the fall 2021 semester. Parents climbed up a flight of stairs — designated P.S. 705-only — to the second floor of a building in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. They walked down squeaky-clean hallways, toured classrooms with desks carefully spaced three feet apart, and heard the whir of newly-installed fans and portable ventilation units.

The event was live-streamed for those who couldn’t make it in person. About 100 parents attended the open house events online and in-person, Principal Valerie Macey estimated, representing around one-third of the school’s 308 students.

The school had already done “a lot of communication,” Macey said — so parents were familiar with safety protocols going into the open house, and questions focused on more typical school concerns such as homework policy. This past communication included weekly town hall meetings, virtual office hours, and individual calls to families.

P.S. 705 went above and beyond New York City school reopening guidance, with a particular reliance on the city’s surveillance testing program. This elementary school had 55% in-person enrollment by the end of the 2020-2021 school year, above the city’s average of about 40%, and made it through the year with just 11 total cases — and zero closures.

P.S. 705 is the subject of the final profile in the COVID-19 Data Dispatch’s “Opening” series. Alongside four other school communities, we selected it because the majority of the school’s students returned to in-person learning during the 2020-2021 school year — and city officials identified COVID-19 cases in under 5% of the student population. (According to the CDC, about 5% of school-aged children in the U.S. contracted COVID-19 between the start of the pandemic and early August 2021.)

As the other four school communities in this project are rural districts — following a trend in our data analysis, which primarily identified rural areas — we felt it was important to include a city school in the project. We additionally wanted to highlight New York State’s surveillance testing program, as it’s one of the few school testing programs with public data available. Plus, the COVID-19 Data Dispatch was able to visit this school in person, as this reporter (Betsy Ladyzhets) is based in Brooklyn.

Demographics for Brooklyn, New York1

Census population estimates, July 2019- Population: 2.6 million

- Race: 36.8% white, 33.8% Black, 18.9% Hispanic/Latino, 12.7% Asian, 2.7% Two or more races, 0.9% Native American

- Education: 82.4% have high school degree, 37.5% have bachelor’s degree

- Income: $60,200 is median household income, 17.7% in poverty

- Computer: 87.5% have a computer, 80.0% have broadband internet

- Free lunch: 67.8% of students receive free or reduced-price lunch2

COVID-19 stats for Brooklyn Arts & Science Elementary School (P.S. 705)

All data from New York School COVID Report Card- Total enrollment: 308 students

- In-person enrollment: 55% at end of the school year

- Total cases, 2020-2021 school year: 11 cases (8 among students, 3 among staff)

1We chose to include borough-level statistics here because the P.S. 705 school district does not clearly align with a specific ZIP code or another smaller geographic area within Brooklyn.

2Source: National Center for Education Statistics

Extensive parent communication

New York City, which has the largest public school district in the U.S., faced challenges with maintaining parent trust during the pandemic. In fall 2020, the city started offering hybrid learning, with cohorts of students returning to classrooms for two or three days a week. But only one in four students actually returned to classrooms by early November, according to the New York Times. In spring 2021, many schools were able to offer five days a week in-person, but most students still stayed home. Parents criticized NYC leaders for confusing communication; teachers protested unsafe conditions at their school buildings; and some staff, like those working with special education students, claimed the city’s plan left them behind.

At P.S. 705, more students returned to in-person learning (55%) than the city average (40%). School administrators made it a priority to provide parents with information and make themselves available for questions. This frequent communication was a major reason why parents felt safe sending their children back to classrooms, representatives from the Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) said in a group interview with administrators and other school staff.

Town halls — livestreamed to parents — are one hallmark of P.S. 705’s communication. After initial school-wide meetings, administrators devised a schedule in which the weekly town halls alternated between grade levels, in order to focus on concerns for specific age groups.

Takiesha Robinson, the PTA president, recalled that these meetings were well-attended; Principal Macey estimated that 30 to 40 parents typically joined the grade-specific events, accounting for the majority of the school’s 40 to 50 students in a grade. “The town halls [were] a very good open forum to let the parents know that you [the administrators] are listening, you do care, you are here,” she said. When parents provided feedback on something they felt wasn’t working, administrators responded quickly, Robinson said.

In addition to the town halls, P.S. 705 administrators staffed a “virtual main office” where parents could enter and ask additional questions. Each morning, administrators logged onto a virtual meeting which stayed live throughout the day. “Parents could come in and ask any questions when they needed,” said Melissa Graham, P.S. 705’s parent coordinator.

School staff also reached out to families proactively when they identified a potential need for support, such as after a student missed class. This school is located on the border of Crown Heights and Prospect Heights, both neighborhoods that were hard-hit by the pandemic: in the school’s ZIP code and in a neighboring ZIP code where families live, one out of every 11 people was diagnosed with COVID-19, according to NYC data.

At P.S. 705 itself, 41% of students are Black and 32% are Hispanic or Latino, two groups that saw disproportionately high COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths in Brooklyn. Principal Macey explained that the staff wanted to know when students lost loved ones or went through other COVID-related struggles.

“The staff and administration went above and beyond to reach out to those families,” said Alison Gilles, PTA secretary. “[The pandemic] definitely hit our community really hard. But 705 is just the kind-of place where it is a ‘wrap your arms around the whole family’ kind-of a school.”

Surveillance testing

At P.S. 705, students get swabbed in the school auditorium. Students wait in socially-distanced seats before returning to class. Photo taken by Betsy Ladyzhets (COVID-19 Data Dispatch). P.S. 705 utilized NYC’s COVID-19 testing program to identify cases before they turned into outbreaks. Starting in October 2020, the NYC Department of Education (DOE) required all schools open for in-person learning to test 20% of their on-site students and staff once a month. In December, as the winter COVID-19 surge grew, this requirement was increased to once a week.

Through partnerships between the city DOE and PCR testing labs, students and staff could get tested right at their school buildings, with results available in two to three days. At P.S. 705, students were tested in the school auditorium, one grade at a time: students filed in at one side of the room, got swabbed one by one, then waited in socially-distanced seats to return to class.

For this school, the city’s 20% requirement shook out to about 45 people. But P.S. 705 “over-volunteered for the testing,” according to DOE spokesperson Nathaniel Styer. Administrators realized that testing was a great tool to keep their classrooms safe and encouraged staff and students to get swabbed even when it wasn’t required.

“There were a lot of people apprehensive, initially, about being tested,” said Principal Macey. So, she, along with Graham (the parent coordinator) and Assistant Principal Kristen Pelekanakis, routinely got tested first so that students and staff could see how easy the process was. During the week of January 20, 2021, for example, over 150 staffers and students were tested—out of about 200 total people in the building.

!function(){“use strict”;window.addEventListener(“message”,(function(e){if(void 0!==e.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var t=document.querySelectorAll(“iframe”);for(var a in e.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var r=0;r<t.length;r++){if(t[r].contentWindow===e.source)t[r].style.height=e.data["datawrapper-height"][a]+"px"}}}))}();Just as young students got used to masks in Oregon, the Brooklyn students got used to swabs. Graham recalled: “I would come into the classroom with a clipboard, and I would have kids being like, ‘Take me! Take me! I’m getting tested this week!’”

In fact, Pelekanakis said that she and other administrators wished testing capacity was higher, so that they could test even more students. The majority of the school’s active cases were caught through random testing, she said; those students were asymptomatic and, she believed, likely wouldn’t have been identified as infected if not for P.S. 705 testing above their required level. The school saw a total of eight student cases and three staff cases all year — comprising just under 5% of the onsite students and staff.

The city’s testing requirement has become less stringent for fall 2021. Now, only 10% of unvaccinated students will be tested every other week, and students must opt in to the program rather than requiring testing for all. According to Principal Macey, all the students who attended in-person classes in spring 2021 had opted into the fall testing program as of early September; she plans on heavily promoting the program to the students who were remote last year through upcoming town halls and other communication.

Macey and the other staffers — who must be vaccinated with at least one dose by the end of September, per a city-wide mandate — aren’t required to participate in testing this fall. But Macey still intends to serve as an example for her students: “I’ll test, just because I want my kids to see,” she said.

Returning to one school community

NYC is heading into the fall 2021 semester with no remote option. At P.S. 705, this means more than 100 students who learned remotely for the entire 2020-2021 school year will be coming back to classrooms. Administrators are preparing with more parent communication (weekly town hall meetings and the late-August open house), while the DOE updates their building’s ventilation system.

In addition to an upgraded mechanical ventilation system, P.S. 705 is utilizing open windows, fans, and portable air filtration units. The building also saw extensive cleaning this summer: Principal Macey wanted to see her face “shining in the floor” by the first day of class. Photos taken by Betsy Ladyzhets (COVID-19 Data Dispatch). The COVID-19 Data Dispatch (CDD) visited P.S. 705 on Sept. 3, just ten days before classrooms open for the new school year. At that time, Principal Macey said the school just finished an overhaul of its HVAC system, updating ventilation throughout the building. The school also had external filtration units, fans, and windows open for additional airflow. In classrooms, desks are spaced three feet apart — down from six feet last year. And custodians are making the building look like new: During the CDD’s visit, Principal Macey told a custodian that she wants to see her face “shining in the floor” by the first day of school.

Summer renovations at P.S. 705 were extensive, according to reporting at Gothamist: In mid-August, “the building that houses Brooklyn Arts and Science Elementary School reported that all 40 of its classrooms were under repair.” At the time of publishing, just one classroom is still marked under repair by the DOE, while three rooms (two staff offices and a bathroom) have no mechanical ventilation.

At the Sept. 3 visit, administrators and teachers told the CDD that they were optimistic about the new school year. “The kids are really good with [keeping] their masks on,” said fourth-grade teacher Denise Garcia. She felt that, with similar protocols in place, the school could continue to have low case counts like the previous year.

This year’s first day of school will be far from typical. Principal Macey has planned for a big celebration, including outdoor activities, a literal red carpet, photo opportunities, and a moment of silence for loved ones lost in the pandemic.

“It can’t just be, ‘go inside, wash your hands,’” she said. “We have to get that space to just reconnect.” With continued communication and acknowledgement of the pandemic’s hardships, she intends to lead her school back into “one school community.”

The COVID-19 Data Dispatch’s “Opening” series is available for other publications to republish, free of charge. If you or your outlet is interested in publishing any part of this series, please contact betsy@coviddatadispatch.com.

More from the Opening series

-

National numbers, September 12

COVID-19 cases appear to be going down in the U.S., though some of that drop may be due to Labor Day reporting delays. Chart from the CDC, retrieved September 12. In the past week (September 4 through 10), the U.S. reported about 960,000 new cases, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 137,000 new cases each day

- 291 total new cases for every 100,000 Americans

- 13% fewer new cases than last week (August 29-September 3)

Last week, America also saw:

- 82,000 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals (25 for every 100,000 people)

- 7,500 new COVID-19 deaths (2.3 for every 100,000 people)

- 99% of new cases now Delta-caused (as of September 4)

- An average of 700,000 vaccinations per day (per Bloomberg)

Last week, I wrote that national U.S. COVID-19 cases were in a plateau. The pattern has continued this week: cases are down 13% from last week, new hospitalized patients are down 4%, and deaths are down 11%.

It’s important to note here, though, that Labor Day likely skewed these numbers. As is typical of COVID-19 reporting on holidays, many local public health agencies—the initial source of case counts and other metrics—took the weekend off, leading those counts to get delayed. We may see higher numbers next week as reports catch up.

Even as the national numbers drop, though, some states are seeing record case counts and overwhelmed hospitals. South Carolina is one example: this state is now seeing the highest case rate in the U.S., with 680 new cases for every 100,000 residents in the past week, per Community Profile Report data. Kentucky and West Virginia are ranking highly too, with 625 and 586 new cases for every 100,000 people in the past week, respectively.

Both South Carolina and Kentucky have record numbers of COVID-19 patients in hospitals right now, while West Virginia is approaching its winter 2020 numbers. In Idaho, another state seeing record hospitalizations, state public health leadership placed several northern hospitals under “crisis standards of care,” meaning that clinicians could ration limited resources and prioritize those patients who are deemed most likely to survive.

All of these states, of course, have low vaccination rates—under 50% of their populations are fully vaccinated. While vaccination rates rose nationally in August, dose counts now seem to be going down again: from a daily average of one million last week to 700,000 now.

The Delta variant continues to dominate America’s COVID-19 surge. For several weeks now, this variant has been causing over 99% of new cases. And, while the Mu (or B.1.621) variant has made headlines, this variant appears not transmissible enough to compete with Delta. The CDC COVID Data Tracker Weekly Review noted this week that the Mu variant “reached its [U.S.] peak in late June,” causing under 5% of cases, and “has steadily decreased since.” It’s currently causing just 0.1% of cases, the CDC estimates.

Also, we still aren’t doing enough testing. The overall national PCR test positivity rate is 9.1%, while rapid tests—increasingly popular during the Delta surge—are difficult to find in many settings. A lack of testing makes it difficult to identify all breakthrough cases and look out for future variants that may arise.