Last week, a COVID-19 outbreak in Cape Code, Massachusetts was revealed to be the subject of a major CDC study providing evidence of the Delta variant’s ability to spread through vaccinated individuals. The outbreak quickly became the subject of national headlines, many of them sensationalizing Delta’s breakthrough potential—while failing to provide much context on the people who actually got sick.

Here’s one big piece of context. Provincetown, the center of this outbreak, is one of America’s best-known gay communities, and the outbreak took place during Bear Week. Bear Week, for the uninitiated, is a week of parties for gay, bisexual, and otherwise men-loving men who identify as bears—a slang term implying a more masculine appearance, often facial and body hair.

This week, I had the opportunity to talk to Mike, a Bear Week attendee from Pittsburgh who caught COVID-19 in Provincetown. (Mike asked me to use only his first name to protect his privacy.) He told me about his experience attending parties, getting sick, and learning about the scale of the outbreak.

We also discussed how Provincetown and the Bear Week community were uniquely poised to identify this outbreak, thanks to a better-than-average local public health department and a group of men who were willing to share their health information with officials.

The interview below has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Betsy Ladyzhets: My first question is just like, how are you doing? How have you been after being involved in this outbreak?

Mike: I’m good… I live in Pittsburgh, I drove back on that Saturday [after the week of Provincetown events] and on Sunday, I started coughing really bad as I was driving home. This just came out of nowhere. I had to pull over, I’m like, yeah, I’m not good. This cough was a lot worse than I had anticipated. So, that was my first symptom. I went into the office Monday after getting home… My first test was negative, on like Monday or Tuesday. But like, I’m still coughing. I didn’t fully trust it. So I got another one Friday, a PCR test.

BL: So, you got tested twice? Did you experience contact tracing, or how did you get identified as part of the outbreak?

M: I mean, I just knew I’d been there. Um, no one reached out but… There was a Facebook group, probably ten or fifteen thousand people in it. Lots of people posted about their test results. Like, people after they were leaving [Provincetown], started quarantining.

The thing about Provincetown is, there were events that happened in the first week [of July, for July 4] that no one really had time to process… Then Bear Week, the week I went, I went at the busiest week of the year for the town. And it had to be, from a planning perspective, I don’t know that was necessarily the best time to have two huge events back to back.

All the official events for the week that I went were canceled, though there were some of the regular bars and stuff doing events. There was, at the time, I think one venue that has a mostly outdoor party every day from like three to seven, that was very heavily attended with one or two thousand people every day, mostly outside and it’s possible to distance at. I only ended up going once or twice just because it wasn’t really where I wanted to be regardless of COVID risks, it wasn’t particularly a scene that I was craving at the time.

I only went to, maybe, three or four indoor things the whole time, and it was without a mask for two or three of them. There’s a bunch of nightclubs in Provincetown that were still having events. And I don’t think that any of the bars themselves that were having events were requiring vaccination cards or anything. One venue that I saw a show at, they announced the next day that they were making either masks or proof of vaccination required. One of the venues that has outdoor events, they just moved all their shows outside instead of inside.

BL: I see. And you mentioned the Facebook group, was that how you found out that a lot of people were getting tested and things like that?

M: Yeah, there were somewhere between ten and fifteen thousand people in the group, planning this whole week. People usually come to Provincetown from all over, sometimes from abroad, though I don’t think there were many people coming from abroad this year because of the restrictions.

BL: How did you learn about the big CDC study getting written about this?

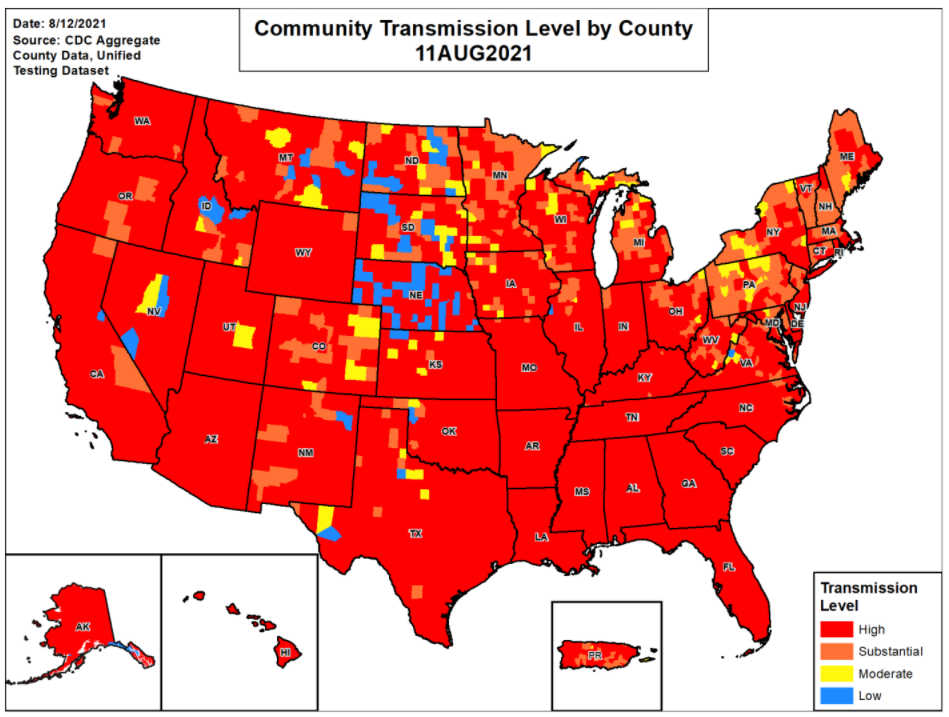

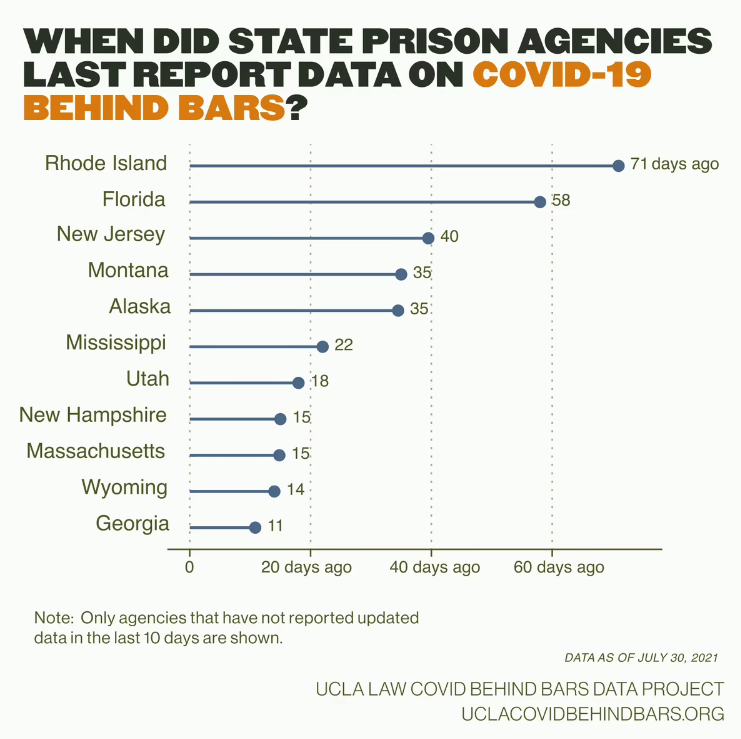

ML: I didn’t really have any idea until afterwards. There were lots of people in the group saying that Barnstable County, or the Massachusetts Department of Health, wanted to know—they wanted people to call if they’d gotten a positive test so they could keep better track of it. I mean, I think part of why the report was able to happen was that it was in a place with better respect for public health than, like, the state of Florida would have, if this kind of outbreak would’ve happened there.

B: Yeah, I mean, it definitely seems like they responded quickly. Because I know they had, like, a 15% positivity rate one week, and then within a pretty short time it was back down.

M: The town itself is a mostly gay, retirement-somewhat community. They can spend lots of money on other things [like public health]. They’re not necessarily spending money on schools because of how many people don’t have any kids around that they need to spend money on. And I mean, there are a lot of residents who live there year-round who tend to be older and are at more risk.

So the week [Bear Week] itself is unique, and then there was a huge community presence about it, everyone wanted to be—for the most part, we’re comfortable about reporting afterwards. I don’t think anyone knew, walking into this, what it would lead to, but… there’s a feeling of community, and that ten thousand-ish Facebook group, I don’t think we otherwise would have necessary talked to each other or told each other about Massachusetts [public health department] asking people to call if they were positive.

BL: And did you do that? Did you call them?

M: Um, I personally didn’t, since I didn’t even find out I was positive until a few days later.

BL: Now, as you know, this outbreak has gotten a lot of national coverage, it’s been kind of sensationalized, with a lot of people focusing on the vaccine breakthrough cases and stuff like that. I know you were not personally one of the people whose test measurements are included there. But what is that experience like of being part of this thing that has gotten so much national attention?

M: I posted about it on social media and there were lots of people who were surprised or whatnot. I think, at least in my head, I went in with a calculated risk, of like 10, 20, 30, or more in the ten thousand-ish people coming, a lot of them are traveling on planes. I drove, thinking I’ll come into this place and I think I’ll make okay decisions…

And there were people in this one place for a whole week, that I guess you were able to test from the CDC’s perspective. I don’t think there are many other places that are as remote as Provincetown where people are staying for the entire week, and everyone generally leaves on the same day, and everyone was in conversation with one another, talking about what happened.

Related links