In the past week (July 10 through 16), the U.S. reported about 184,000 new cases, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 26,300 new cases each day

- 56 total new cases for every 100,000 Americans

- 69% more new cases than last week (July 3-9)

Last week, America also saw:

- 19,600 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals (6.0 for every 100,000 people)

- 1,500 new COVID-19 deaths (0.5 for every 100,000 people)

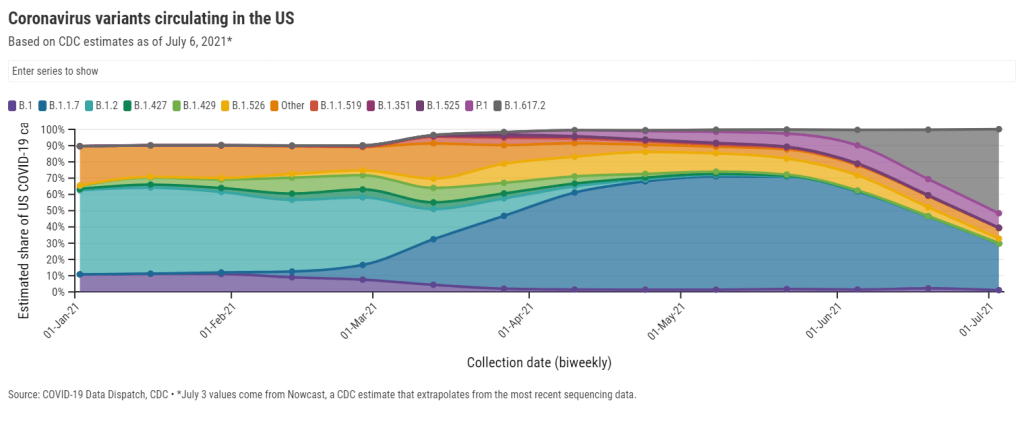

- 58% of new cases now Delta-caused (as of July 3)

- An average of 500,000 vaccinations per day (per Bloomberg)

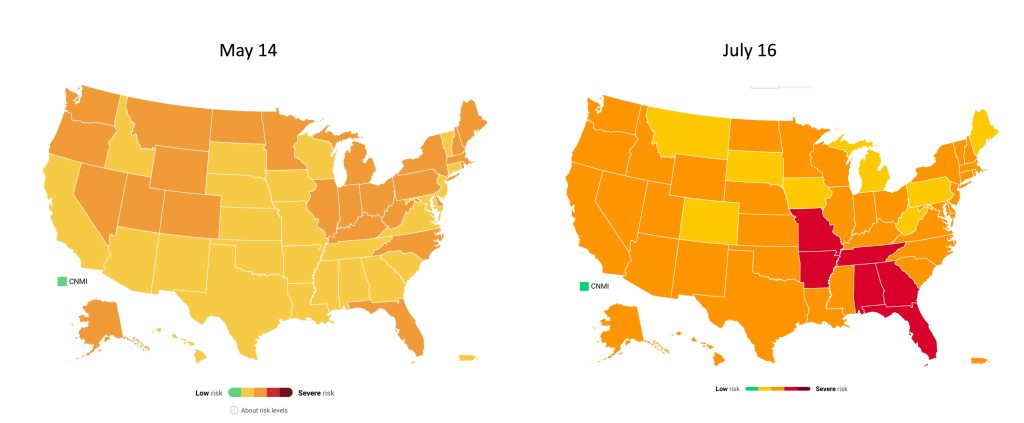

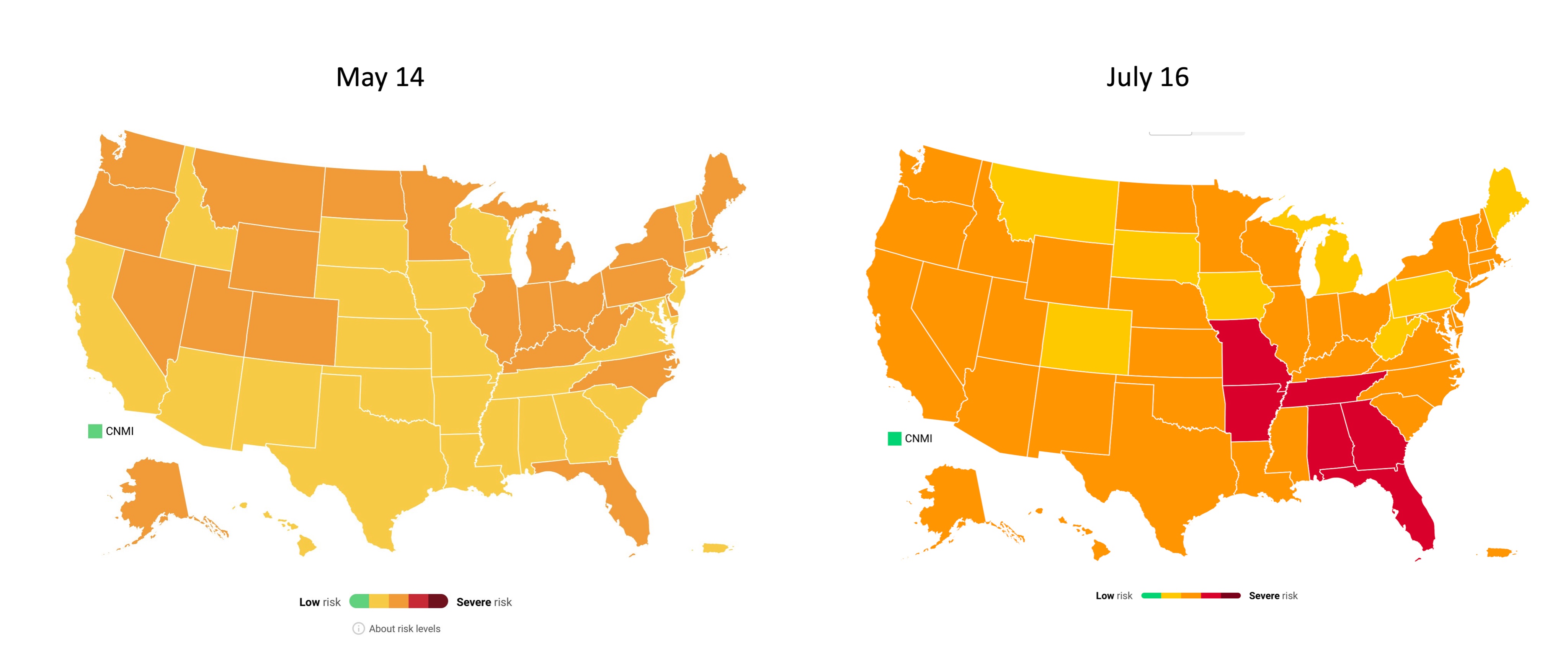

Cases have been rising for a couple of weeks now, but we’re now seeing the sharpest increase since fall 2020. Between July 9 and July 16, we went from an average of 15,000 new cases a day to an average of 26,000 new cases a day.

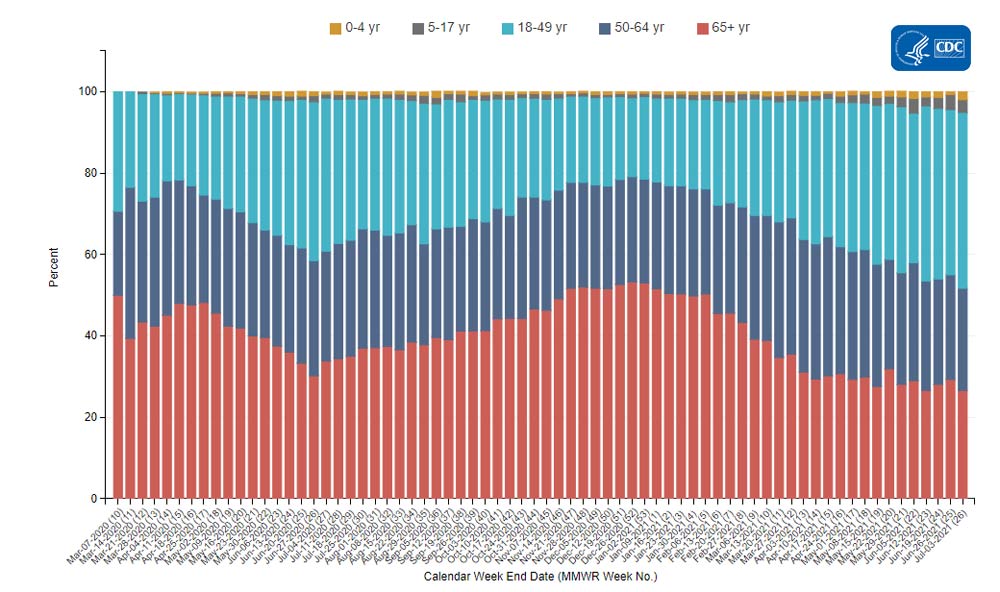

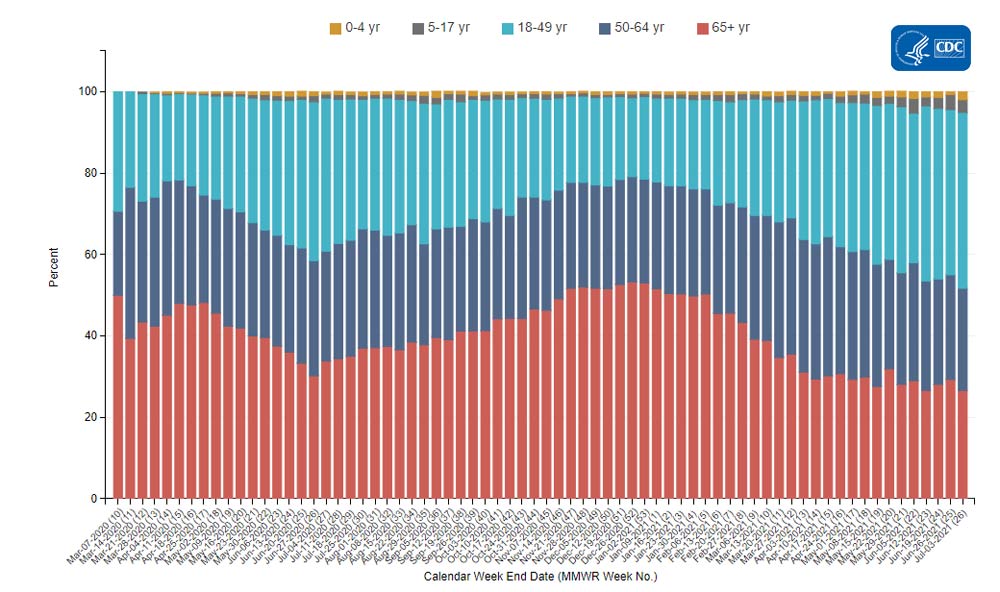

Hospitalizations and deaths are also increasing. We’re now seeing about 26% more new COVID-19 patients in hospitals every day and 36% more new deaths—it’s the first time that deaths have increased since the winter.

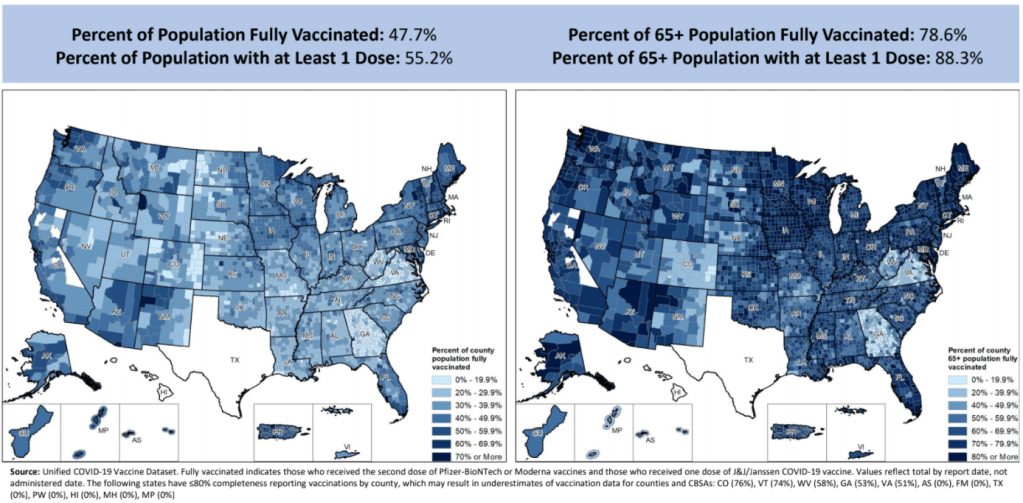

“There is a clear message that is coming through: this is becoming a pandemic of the unvaccinated,” CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky said at a press briefing on Friday. As I’ve continually emphasized in recent issues, states and counties with lower vaccination rates are more vulnerable to the Delta variant.

Missouri continues to be a hotspot, as does Arkansas, with other states in the Midwest and South also seeing major surges. Florida is of particular concern: one in five U.S. cases in the last week were reported in this state, and Florida has seen a 109% case increase from the first to the second week of July.

The under-vaccinated hotspots are more likely to see hospitals become overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients (see: this great data visualization by Conor Kelly). But even areas with high vaccination rates are seeing Delta take over. In New York City, Delta now causes 69% of new cases—and case numbers have doubled in the past two weeks. In San Francisco, where a full three-quarters of the eligible population is fully vaccinated, cases and test positivity rates have jumped in July.

Despite the clear dangers of Delta, millions of Americans still refuse to get vaccinated. As Ed Yong put it in a recent piece on Missouri’s surge: “Vaccines were meant to be the end of the pandemic. If people don’t get them, the actual end will look more like Springfield’s present: a succession of COVID-19 waves that will break unevenly across the country until everyone has either been vaccinated or infected.”