In January, I invited readers to fill out a survey asking what you’d like to see from the COVID-19 Data Dispatch in 2022. Thank you to everyone who responded—your feedback gave me some great ideas for topics to focus on and new CDD-related initiatives to pursue this year!

This week, though, I want to focus on a topic that multiple readers brought up in the survey: how individuals can impact COVID-19 policies. One reader asked, “What can I as an individual do to make better the lacking local, state, federal, and international societal responses to COVID-19?” Another reader asked, along the same lines, “What can I do to encourage policy changes that keep people safer?”

These questions feel particularly pertinent this week, as leaders of several states loosen up on mask mandates and other COVID-19 safety measures. Governors in New Jersey, Connecticut, Delaware, Oregon, and Massachusetts have all announced that they’re ending mask mandates in public schools, and in some cases, in other public spaces. New York Governor Kathy Hochul is keeping the state’s K-12 school mask mandate in place for now, but ending a mandate for New York businesses.

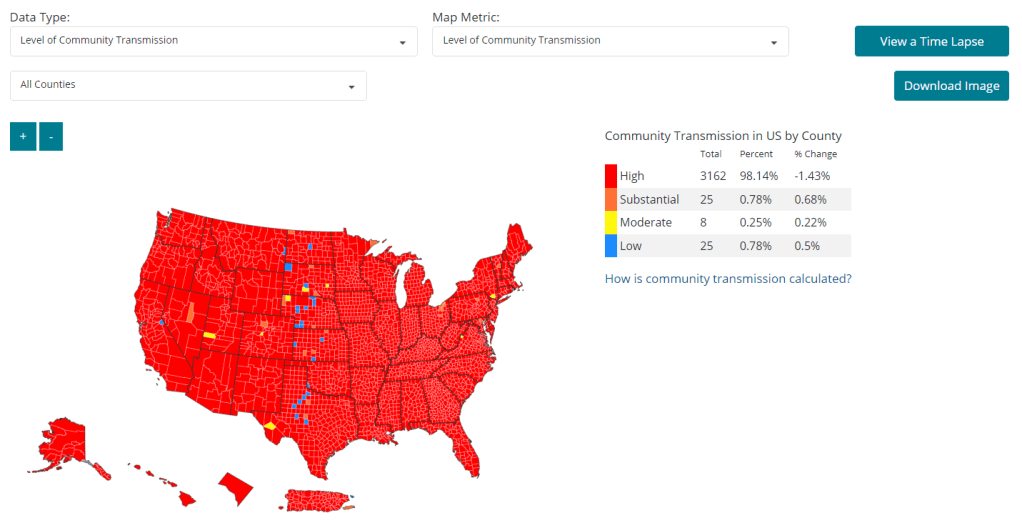

Policy changes like these go against long-standing guidance from the CDC. In summer 2021, the agency recommended that communities base their levels of COVID-19 safety measures on two primary metrics: new cases per 100,000 people in the last week, and the percent of PCR tests that returned positive results in the last week. A high case rate indicates a lot of COVID-19 in the community, while a high test positivity rate can indicate the community’s testing infrastructure is not picking up a large share of cases—both suggest that measures should be put in place to control the virus’ spread.

At the time, this guidance was instituted as a response to the CDC’s preemptive recommendation that vaccinated people could go maskless. The agency said that counties seeing “high” or “substantial” transmission, according to the CDC’s metrics, should mandate masks for all, while counties with lower transmission could allow vaccinated people to go maskless. Gotta be honest: I do not know of a single state or county that’s actually following this guidance. Still, this combination of metrics is, I find, a useful and simple way to evaluate community spread.

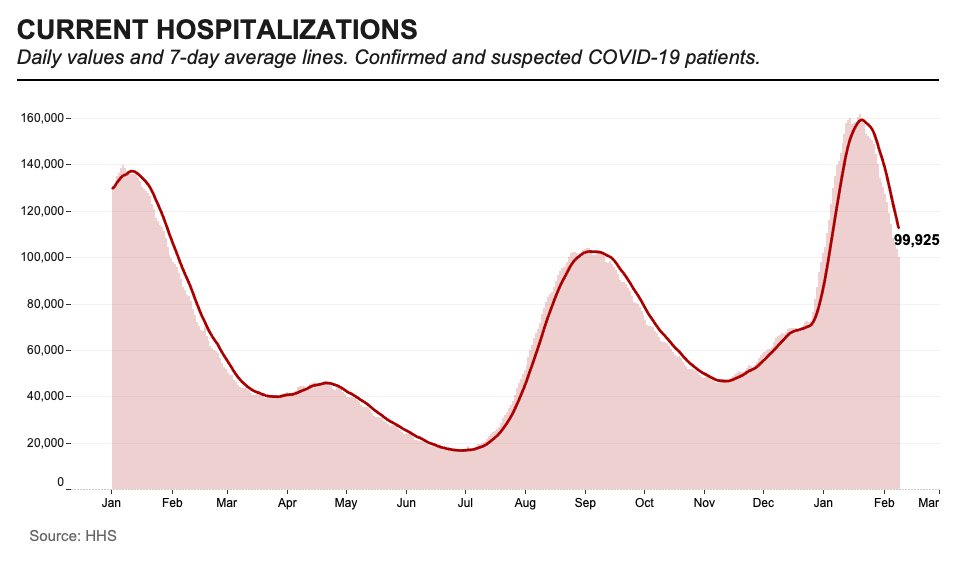

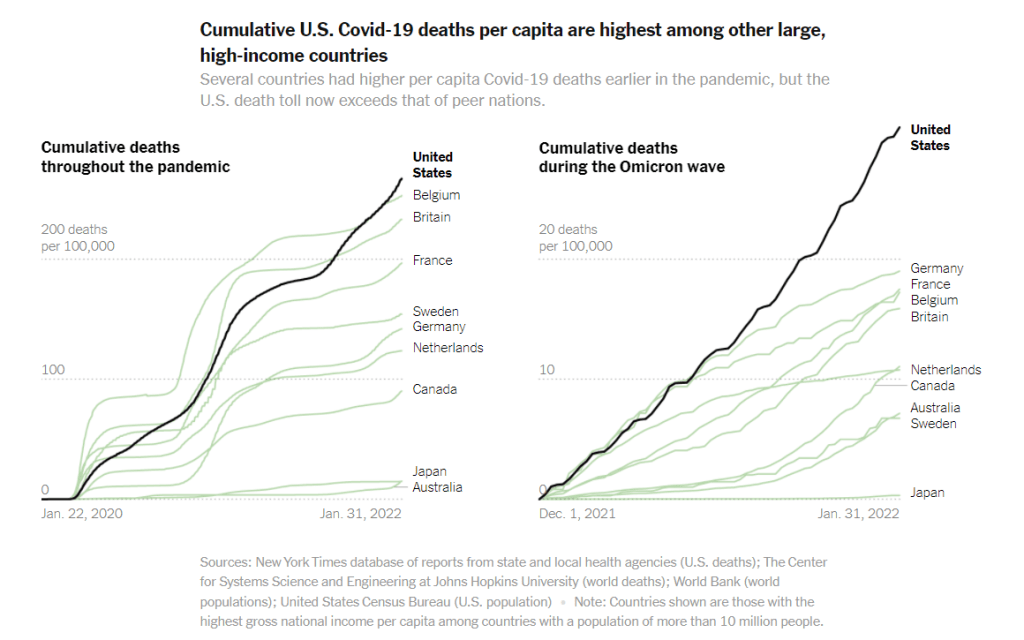

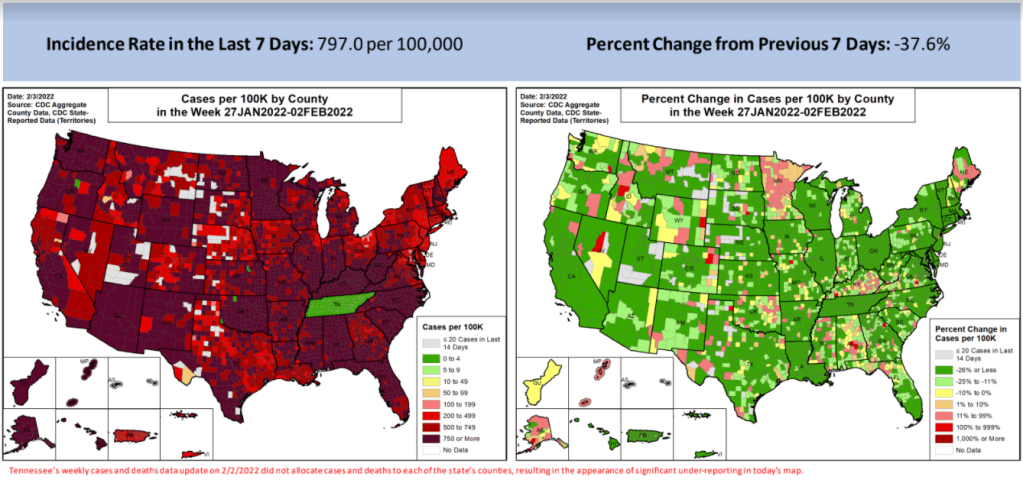

As I’ve pointed out in recent National Numbers updates, even though case numbers in the U.S. have dropped significantly since the Omicron peak in January, they are still at very high levels across the country. You can see on the CDC’s dashboard that, as of this week, about 98% of counties fall into the “high transmission” category—with over 100 new cases per 100,000 people and test positivity over 10%. And beyond the case numbers: many hospitals are currently recovering from record Omicron surges, while over 2,000 Americans are dying of COVID-19 each day.

According to the CDC’s own guidance, 98% of U.S. counties should have a mask mandate right now. But instead, among the small number of Democrat-led states that have retained mandates, safety measures are now being lifted. The CDC itself is having a hard time commenting on this situation, and is reportedly “considering updating its guidelines on the metrics states should use,” according to POLITICO.

During this time of “opening” the small number of places that were not already fully open, what can individuals do to make their voices heard—or at least improve COVID-19 safety in their own communities? I have three suggestions:

1. Call your political representatives and tell them how you feel.

If your state, city, or other local region is considering lifting some COVID-19 safety measures, you have a representative whose job literally includes listening to your complaints about this issue—whether that’s a state assembly member or city councilor.

You can use this website to find your national and state representatives, and many localities have their own equivalents (for example, this site for New York City). Once you’ve found the contact information for your representatives, call or email them to express your support for continued COVID-19 precautions. This document offers a couple of potential phone call and email scripts; it’s New York-specific, but can easily be translated to other states.

In the last couple of years, conservative Americans have often been more politically active at the local level than more left-leaning Americans. Republicans often show up to school board meetings, call their representatives, and make their anger heard—sometimes supported by astroturfing campaigns. Anecdotal reports suggest that public health officials tend to hear more from community members who hate mandates than from those who actually want to see COVID-19 safety in their communities. You can push back against this trend.

And if you want to do some additional phone-calling or emailing beyond political representatives, consider reaching out to your state or local public health department and offering some support! They can probably use it.

2. Volunteer for local organizations helping to provide vaccinations, masks, tests, and other resources.

About 80% of Americans ages five and up have received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose, according to the CDC. This number may sound impressive, but’s more concerning when we look at the other side of the statistic: 20% of eligible Americans have not yet received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose. Plus, among those Americans who have been fully vaccinated, more than half haven’t received a booster shot.

A lot of unvaccinated Americans are conservatives whose minds are very hard to change, this is true. But many of them are low-income workers with intense schedules, lingering health concerns, and other barriers to actually getting the shots that are surmountable, health policy expert Julia Raifman told me for a FiveThirtyEight story last month.

As a result, volunteer organizations around the country are still working to get their communities vaccinated and boosted. For example, Bed-Stuy Strong, a mutual aid group in my Brooklyn neighborhood, has hosted vaccination drives focused on local seniors and disseminated information on vaccinations and testing in the area.

Look for an effort like this that you might be able to join in your community! Or, if nothing like this currently exists, reach out to a local organization—like a public school, library, community center, etc.—and see if they might want to host a vaccine drive. Your local public health department could likely provide the supplies.

3. Educate your friends, family, and community members.

Beyond political and volunteer efforts, you can increase COVID-19 safety in your community simply by spreading the word about tools like high-quality masks and rapid tests. It might seem obvious, at this point in the pandemic, that we should all be stocking up on KN95s and testing kits, but many people do not have access to these tools—or simply don’t know why they’re useful.

You can send friends, family, and community members to websites like Project N95, which sells masks and other PPE, and Bona Fide Masks, a family business and leading KN95/N95 distributor. You can also tell them about antigen test distributors like iHealth Labs and Walmart, which are seeing fewer delays and supply crunches as the Omicron surge wanes.

In addition, if you have the resources, you can buy these masks and rapid tests in bulk and give them out. I recently gave out a couple of KN95 masks to contractors who were sent to look at a water issue in my apartment building, because I had the masks to spare. It’s that easy!

If you take any of these suggestions and see some impact, please email me (betsy@coviddatadispatch.com) and tell me about it!