As COVID-19 safety measures are lifted and agencies move to an endemic view of the virus, I’m thinking about my shifting role as a COVID-19 reporter. To me, this beat is becoming less about reporting on specific hotspots or control measures and more about preparedness: what the U.S. learned from the last two years, and what lessons we can take forward—not just for the future COVID-19 surges that are almost certainly coming, but also for future infectious disease outbreaks.

To that end, I was glad to see the Biden administration release a new COVID-19 plan focused on exactly this topic: preparedness for new surges, new variants, and new infectious diseases beyond this current pandemic.

From the plan’s executive summary:

Make no mistake, President Biden will not accept just “living with COVID” any more than we accept “living with” cancer, Alzheimer’s, or AIDS. We will continue our work to stop the spread of the virus, blunt its impact on those who get infected, and deploy new treatments to dramatically reduce the occurrence of severe COVID-19 disease and deaths.

The Biden plan was released last week, in time with the president’s State of the Union address. I read through it this morning, looking for goals and actions connected to data collection and reporting.

Here are a few items that stuck out to me, either things that the Biden administration is already doing or should be doing:

- Improving surveillance to identify new variants: The U.S. significantly improved its variant sequencing capacity in 2021, multiplying the number of cases sequenced by more than tenfold from the beginning to the end of the year. But the new Biden plan promises to take these improvements further, by adding more capacity for sequencing at state and local levels—and, crucially, “strengthening data infrastructure and interoperability so that more jurisdictions can link case surveillance and hospital data to vaccine data.” In plain language, that means: making it easier to track breakthrough cases (which I have argued is a key data problem in the U.S.).

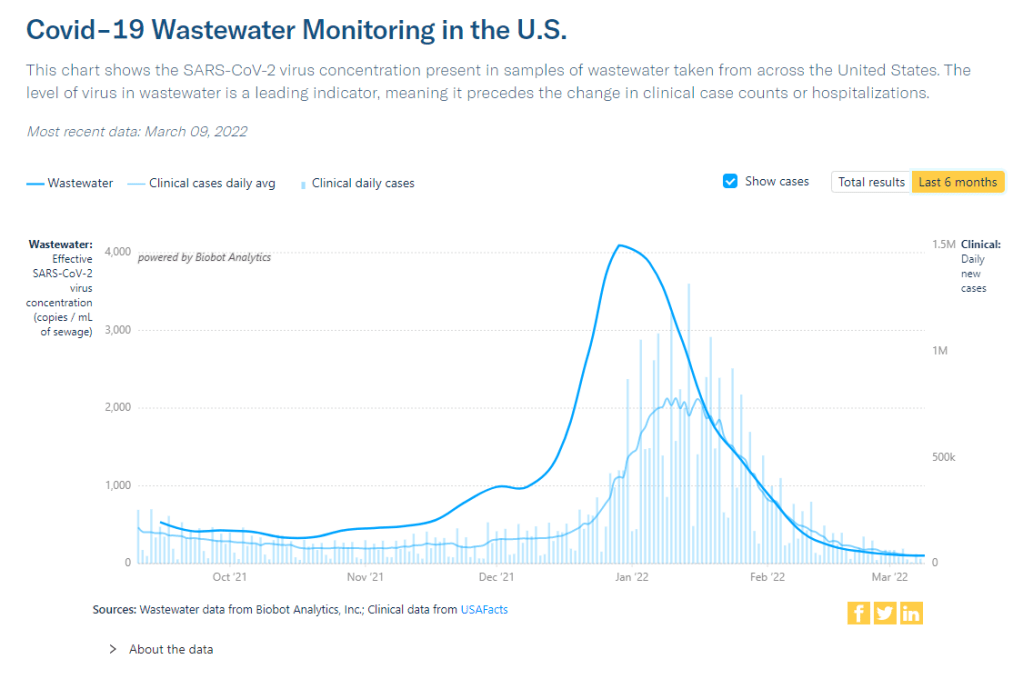

- Expanding wastewater surveillance: As I’ve written before, in the current national wastewater surveillance network, some states are very well-represented with over 50 collection sites; while other states are not included in the data at all. The Biden administration is committed to bring more local health agencies and research institutions into the surveillance network, thus expanding our national capacity to get early warnings about surges.

- Standardizing state and local data systems: I’ve written numerous times that the U.S. suffers from a lack of standardization among its 50 different states and hundreds of local health agencies. According to the new plan, the Biden administration plans to facilitate data sharing, aggregating, and analyzing data across state and local agencies—including wastewater monitoring and other potential methods of surveillance that would provide early warnings of new surges. This would be huge if it actually happens.

- Modernize the public health data infrastructure: One thing that could help health agencies better coordinate and share data: modernizing their data systems. That means phasing out fax machines and mail-in reports (which, yes, some health departments still use) and investing in new electronic health record technologies, while hiring public health workers who can manage such systems.

- Use a new variant playbook to evaluate new virus strains: Also in the realm of variant preparedness, the Biden administration has developed a new “COVID-19 Variant Playbook” that may be used to quickly determine how a new variant impacts disease severity, transmissibility, vaccine effectiveness, and other factors. The new playbook may be used to quickly update vaccines, tests, and treatments if needed, by working in partnership with health systems and research institutions.

- Collecting demographic data on vaccinations and treatments: The Biden plan boasts that, “Hispanic, Black, and Asian adults are now vaccinated at the same rates as White adults.” However, CDC data shows that this trend does not hold true for booster shots: eligible white Americans are more likely to be boosted than those in other racial and ethnic groups. The administration will need to continue collecting demographic data to identify and address gaps among vaccinations and treatments; indeed, the Biden plan discusses continued efforts to improve health equity data.

- Tracking health outcomes for people in high-risk settings: Along with its health equity focus, the Biden plan discusses a need to better track and report on health outcomes in nursing homes, other long-term care facilities, and other congregate settings like correctional facilities and homeless shelters. Congregate facilities continue to be major COVID-19 hotspots whenever there’s a new outbreak, so improving health standards in these settings should be a major priority.

- Studying and combatting vaccine misinformation, vaccine safety: The new plan acknowledges the impact of misinformation on vaccine uptake in the U.S., and commits the Biden administration to addressing this trend. This includes a Request for Information that will be issued by the Surgeon General’s office, asking researchers to share their work on misinformation. Meanwhile, the administration will also continue monitoring vaccine safety and reporting these data to the public.

- Test to Treat: One widely publicized aspect of the Biden plan is an initiative called “Test to Treat,” which would allow people to get tested for COVID-19 at pharmacies, health clinics, long-term care facilities, and other locations—then, if they test positive, immediately receive treatment in the form of antiviral pills. If this initiative is widely funded and adopted, the Biden administration should require all participating health providers to share testing and treatment data. This would allow researchers to evaluate whether this testing and treatment rollout has been equitable across different parts of the country and minority groups.

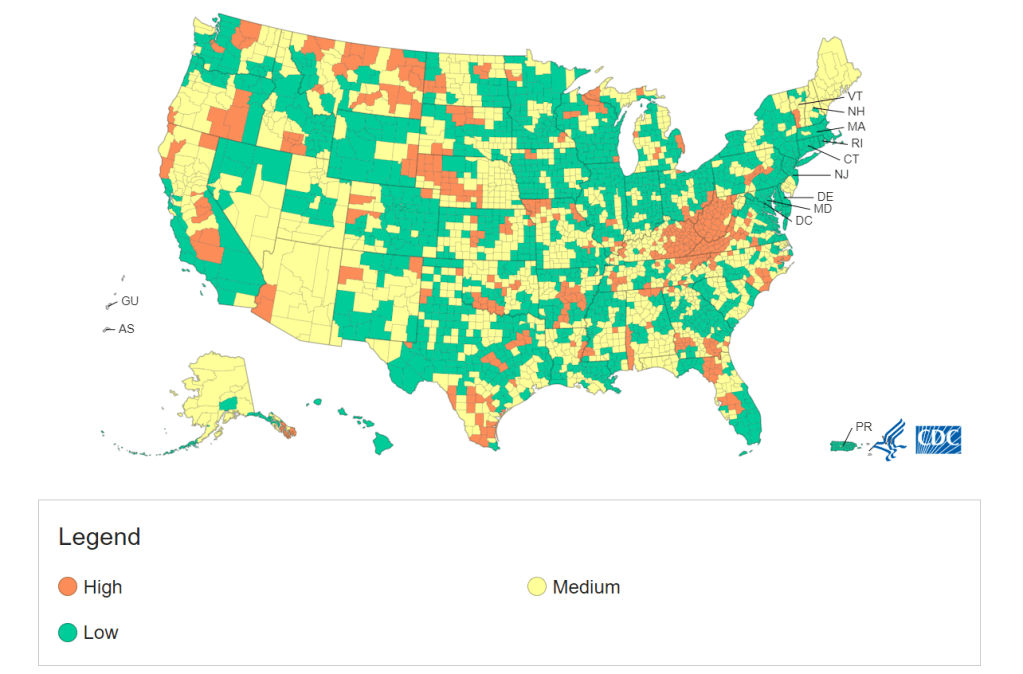

- Website for community risk levels and public health guidance: The Biden plan includes the launch of a government website “that allows Americans to easily find public health guidance based on the COVID-19 risk in their local area and access tools to protect themselves.” The CDC COVID-19 dashboard was recently redesigned to highlight the agency’s new Community Level guidance, which is likely connected to this goal. Still, the CDC dashboard leaves much to be desired when it comes to comprehensive information and accessibility, compared to other trackers.

- A new logistics and operational hub at HHS: In the last two years, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) built up an office for coordinating the development, production, and delivery of COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. The new Biden plan announced that this office will become a permanent part of the agency, and may be used for future disease outbreaks. At the same time, the Biden administration has added at-home tests, antiviral pills, and masks to America’s national stockpile for future surges; and it is supporting investments in laboratory capacity for PCR testing.

- Tracking Long COVID: Biden’s plan also highlights Long COVID, promoting the need for government efforts to “detect, prevent, and treat” this prolonged condition. The plan mentions NIH’s RECOVER initiative to study Long COVID, discusses funding new care centers for patients, and proposes a new National Research Action Plan on Long COVID that will bring together the HHS, VA, Department of Defense, and other agencies. Still, the plan doesn’t discuss actual, financial support for patients who have been out of work for up to two years.

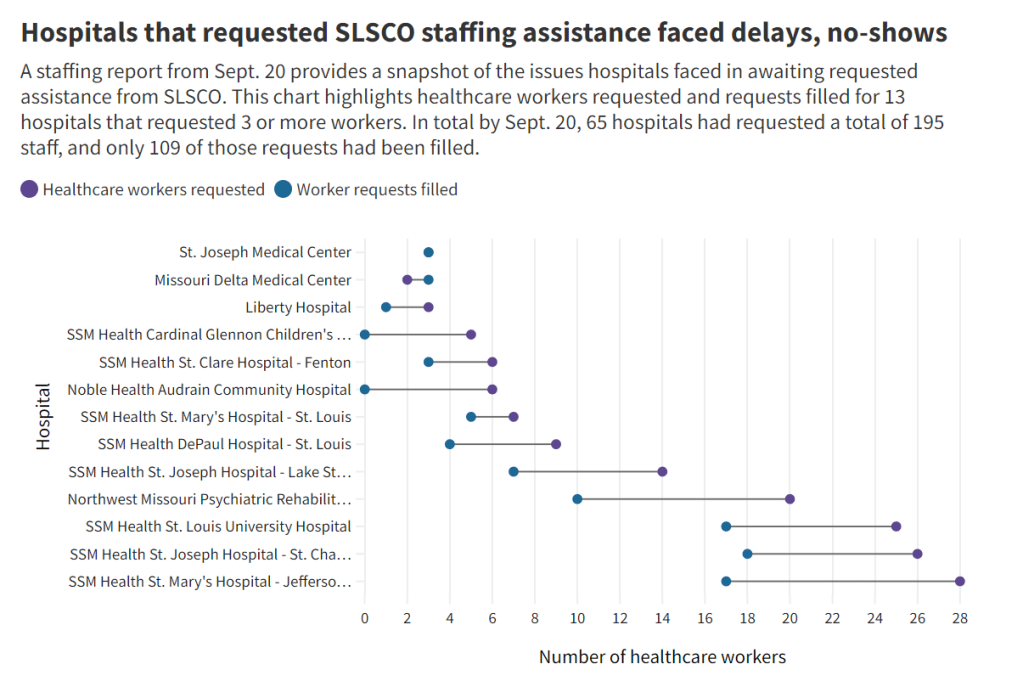

- Supporting health and well-being among healthcare workers: The new Biden plan acknowledges major burnout among healthcare workers, and proposes a new grant program to fund mental health resources, support groups, and other systems of combatting this issue. Surveying healthcare workers and developing systematic solutions to the challenges they face could be a major aspect of preparing for future disease outbreaks. The Biden plan also mentions investing in recruitment and pipeline programs to support diversity, equity, and inclusion among health workers.

- More international collaboration: The new Biden plan also focuses on international aid—delivering vaccine donations to low-income nations—and collaboration—improving communication with the WHO and other global organizations that conduct disease surveillance. This improved communication may be especially key for identifying and studying new variants in a global pandemic surveillance system.

This week, a group of experts—including some who have advised the Biden administration— followed up on the Biden plan with their own plan, called “A Roadmap for Living with COVID.” The Roadmap plan also emphasizes data collection and reporting, with a whole section on health data infrastructure; here, the authors emphasize establishing centralized public health data platforms, linking disparate data types, designing data infrastructure with a focus on health equity, and improving public access to data.

Both the Biden administration’s plan and the Roadmap plan give me hope that U.S. experts and leaders are thinking seriously about preparedness. However, simply releasing a plan is only the first step to making meaningful changes in the U.S. healthcare system. Many aspects of the Biden plan involve funding from Congress… and Congress is pretty unwilling to invest in COVID-19 preparedness right now. Just this week, a $15 billion funding plan collapsed in the legislature after the Biden administration already made major concessions.

Readers, I recommend calling your Congressional representatives and urging them to support COVID-19 preparedness funding. You can also look into similar measures in your state, city, or other locality. We need to improve our data in order to be prepared for future disease outbreaks, COVID-19 and beyond.