Last fall, I wrote—both in the COVID-19 Data Dispatch and for FiveThirtyEight—that the U.S. did not have the data we needed to make informed decisions about booster shots. Several months later, we still don’t have the data we need, as questions about a potential BA.2 wave and other future variants abound. Discussions at a recent FDA advisory committee meeting made these data gaps clear.

Our country has a fractured public health system: every state health department has its own data systems for COVID-19 cases, vaccinations, and other metrics, and these data systems are often very difficult to link up with each other. This can make it difficult to answer questions about vaccine effectiveness, especially when you want to get specific about different age groups, preexisting conditions, or variants.

To quote from my November FiveThirtyEight story:

In the U.S., vaccine research is far more complicated. Rather than one singular, standardized system housing health care data, 50 different states have their own systems, along with hundreds of local health departments and thousands of hospitals. “In the U.S., everything is incredibly fragmented,” said Zoë McLaren, a health economist at the University of Maryland Baltimore County. “And so you get a very fragmented view of what’s going on in the country.”

For example, a database on who’s tested positive in a particular city might not be connected to a database that would reveal which of those patients was vaccinated. And that database, in turn, is probably not connected to health records showing which patients have a history of diabetes, heart disease or other conditions that make people more vulnerable to COVID-19.

Each database has its own data fields and definitions, making it difficult for researchers to integrate records from different sources. Even basic demographics such as age, sex, race and ethnicity may be logged differently from one database to the next, or they may simply be missing. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for instance, is missing race and ethnicity information for 35 percent of COVID-19 cases as of Nov. 7.*

*As of April 9, the CDC is still missing race and ethnicity information for 35% of COVID-19 cases.

This past Wednesday, the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) met to discuss the future of COVID-19 booster shots. Notably, this committee didn’t actually need to vote on anything, since the FDA and CDC had already authorized a second round of boosters for Americans over age 50 and immunocompromised people the week before.

When asked why the FDA hadn’t waited to hear from its advisory committee before making this authorization decision, vaccine regulator Peter Marks said that the agency had relied on data from the U.K. and Israel to demonstrate the need for more boosters—combined with concerns about a potential BA.2 wave. The FDA relied on data from the U.K. and Israel when making its booster decision in the fall, too; these countries, with centralized health systems and better-organized data, are much more equipped to track vaccine effectiveness than we are.

With that authorization of second boosters for certain groups already a done deal, the VRBPAC meeting this past Wednesday focused more on the information we need to make future booster decisions. Should we expect annual COVID-19 shots, like we do for the flu? What about shots that are designed to combat specific variants? A lot of this is up in the air right now, the meeting discussion indicated.

Also up in the air: will the FDA ever host a virtual VRBPAC meeting without intensive technical difficulties? The meeting had to pause for more than half an hour to sort out a livestream issue.

Here are some vaccine data questions that came up on Wednesday, drawing from my own notes on the meeting and the STAT News liveblog:

- How much does protection from a booster shot wane over time? We know that booster shots increase an individual’s protection from a coronavirus infection, symptoms, hospitalization, and other severe outcomes; CDC data presented during the VRBPAC meeting showed that, during the Omicron surge, Americans who were boosted were much more protected than those with fewer doses. But we don’t have a great sense of how long these different types of protection last.

- How much does booster shot protection wane for different age groups? Waning immunity has been a bigger problem among seniors and immunocompromised people, leading to the FDA’s decision on fourth doses for these groups. But what about other age groups? What about people with other conditions that make them vulnerable to COVID-19, like diabetes or kidney disease? This is less clear.

- To what degree is waning immunity caused by new variants as opposed to fewer antibodies over time? This has been a big question during the Delta and Omicron surges, and it can be hard to answer because of all the confounding variables involved. In the U.S., it’s difficult to link up vaccine data and case data; tacking on metrics like which variant someone was infected with or how long ago they were vaccinated often isn’t possible—or if it is possible, it’s very complicated. (The U.K. does a better job of this.)

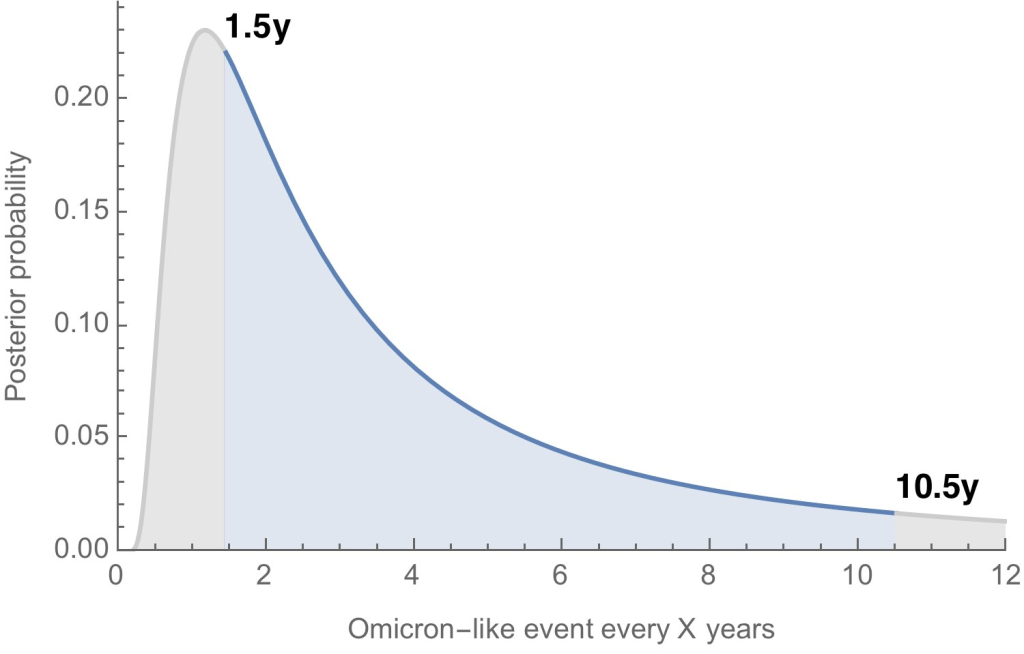

- Where will the next variant of concern come from, and how much will it differ from past variants? Computational biologist Trevor Bedford gave a presentation to VRBPAC that attempted to answer this question. The short answer is, it’s hard to predict how often we’ll see new events like Omicron’s emergence, in which a new variant comes in that is extremely different from the variants that preceded it. Bedford’s analysis suggests that we could see “Omicron-like” events anywhere from every 1.5 years to every 10.5 years, and we should be prepared for anything on that spectrum. The coronavirus has evolved quite quickly in the last two years, Bedford said, and will likely continue to do so; though he expects some version of Omicron will be the main variant we’re dealing with for a while.

- What will the seasonality of COVID-19 be? The global public health system has a well-established process for developing new flu vaccines, based on monitoring circulating flu strains in the lead-up to flu seasons in different parts of the world. Eventually, we will likely get to a similar place with COVID-19 (if annual vaccines become necessary! also an open question at the moment). But right now, the waxing and waning of surges caused by new variants and human behavior makes it difficult to identify the actual seasonality of COVID-19.

- At what point do we say the vaccine isn’t working well enough? This question was asked by VRBPAC committee member Cody Meissner of Tufts University, during the discussion portion of the meeting. So far, the most common way to measure COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in the lab is by testing antibodies generated by a vaccine against different forms of the coronavirus. But these studies don’t account for other parts of the immune system, like T cells, that garner more long-term protection than antibodies. We need a unified method for measuring vaccine effectiveness that takes different parts of the immune system into account, along with real-world data.

- How might vaccine safety change over time? This question was brought up by Hayley Ganz of Stanford, another VRBPAC committee member. The CDC does have an extensive system for monitoring vaccine safety; data from that system should be readily available to the experts making booster shot decisions.

Another thing I’m wondering about right now, personally, is how the U.S.’s shifting focus away from case data might make all of this more complicated. As public health agencies scale down case investigations and contact tracing—and more people test positive on at-home, rapid tests that are never reported to these agencies—we’re losing track of how many Americans are actually getting COVID-19. And breakthrough cases, which are more likely to be mild or asymptomatic, might also be more likely to go unreported.

So, how does the U.S. public health system study vaccine effectiveness in a comprehensive way if we simply aren’t logging many of our cases? Programs such as randomized surveillance testing and cohort studies might help, but outside of a few articles and Twitter conversations, I’m not seeing much discussion of these solutions.

Finally: a few friends and relatives over age 50 have asked me about when (or whether) to get another booster shot, given all of the uncertainties I laid out above. If you’re in the same position, here are a couple of resources that might help:

- Fourth Dose Q&A (Your Local Epidemiologist)

- How to Time Your Second Booster (The Atlantic)

- Do I really need another booster? The answer depends on age, risk and timing (NPR)