This past Friday, the CDC announced a major shift to its guidance for determining COVID-19 safety measures based on county-level community metrics. The new guidance is intended to replace COVID-19 thresholds that the agency developed last summer, during the Delta wave; here, the CDC is promoting a shift from using cases and test positivity for local decision-making to using metrics tied directly to the healthcare system.

This shift away from cases isn’t new: state health departments have been moving in this direction recently, as I wrote last week. Similarly, the CDC’s recommendation for when Americans should feel safe in taking off their masks aligns with recent guidance changes from state leaders.

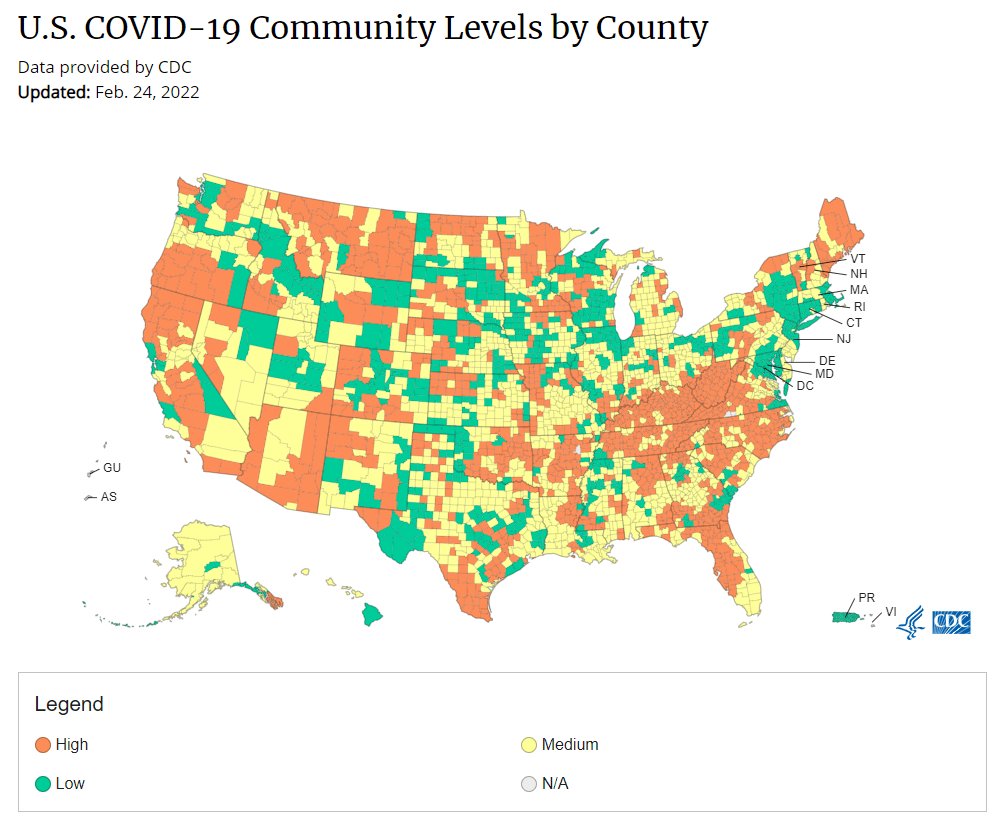

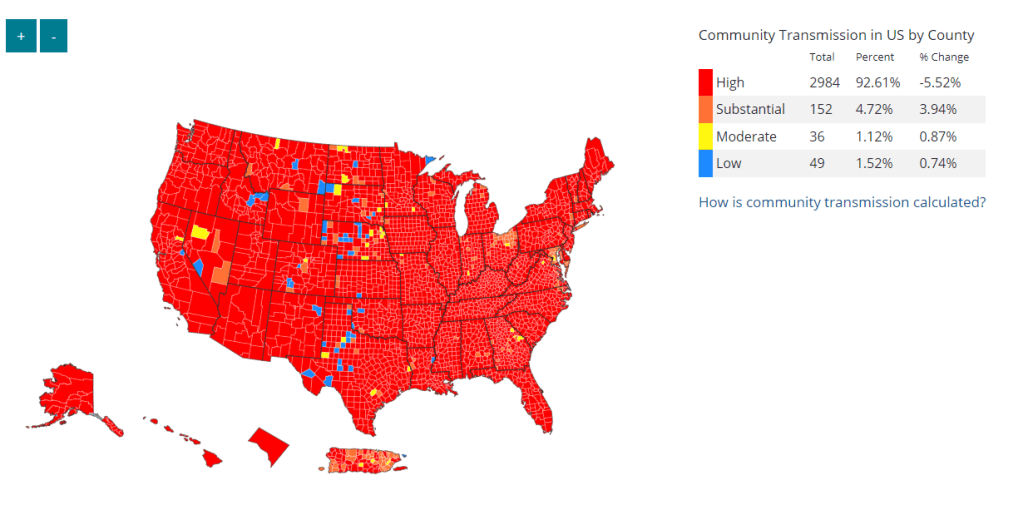

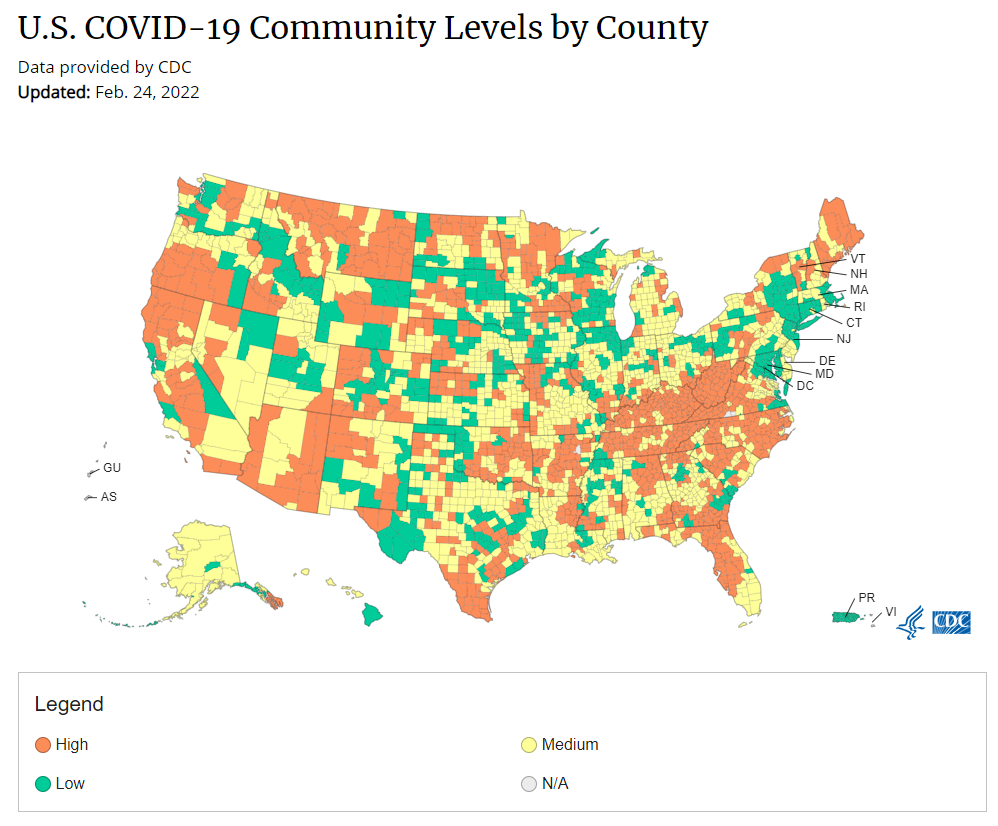

The new guidance is essentially a lot more lenient when it comes to mask removal. Overnight, the U.S. goes from under 5% of counties in “low” or “moderate” transmission (under the old guidance) to over 60% of counties, representing 70% of the population, in a “low” or “medium” COVID-19 community level.

This shift will embolden more states, local health departments, and individual organizations to lift safety measures and change how they track COVID-19. In this post, I’ll unpack why I believe the CDC made certain choices with this new guidance, what critiques I’m seeing from public health experts, and some recommendations for thinking about your COVID-19 risk during this highly confusing pandemic era.

Rationale for the CDC’s new guidance

With this new framework, the CDC is essentially telling Americans to watch hospitalization numbers—not case numbers—as the most important metric to inform how hard COVID-19 is hitting their community. One piece of their logic is, I suspect, that case numbers are less reliable in this pandemic era than they have been since March 2020.

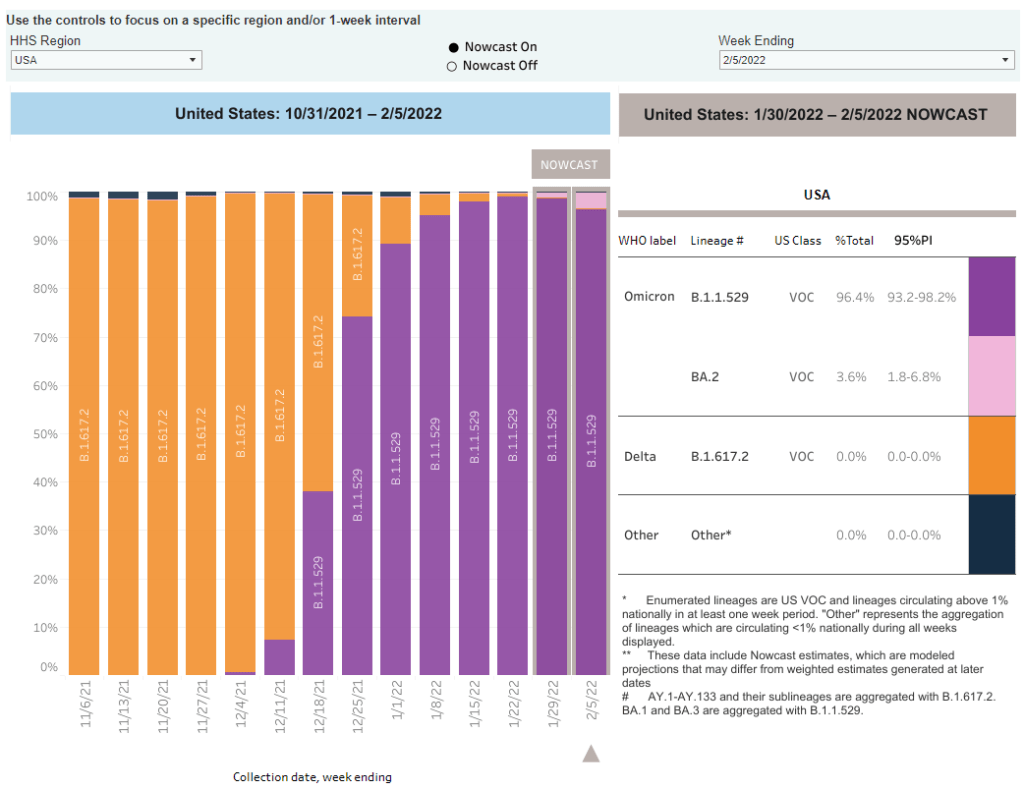

That lack of reliability largely stems from the rise of at-home rapid antigen tests, which gained popularity during the Omicron surge and are now largely unconstrained by supply issues. (For example: iHealth Labs, one major at-home test provider, now allows shoppers to buy up to 50 test kits per person, up from a limit of 10 during Omicron’s peak.)

Unlike PCR test results, which are systematically processed in labs and reported to public health agencies, at-home test results typically do not travel beyond a patient’s trash can. And while a few local jurisdictions (like D.C.) have given residents options to self-report their antigen tests, the majority have opted not to take on this challenge. As a result, current case numbers for almost everywhere in the U.S. are not very reflective of actual infections in the community.

In previous pandemic eras, researchers could use PCR test positivity as an indicator of how reliable case numbers might be for a particular jurisdiction: higher test positivity usually means that more cases are going unreported. But in the era of widespread rapid tests, test positivity is also less reliable, because rapid tests aren’t accounted for in the test positivity calculations either.

Case numbers do still have some utility, because people who have COVID-19 symptoms or need a test result to travel will continue seeking out PCR tests. The CDC guidance reflects this by keeping cases as one factor of its COVID-19 community level calculation. But cases are no longer the star of the show here.

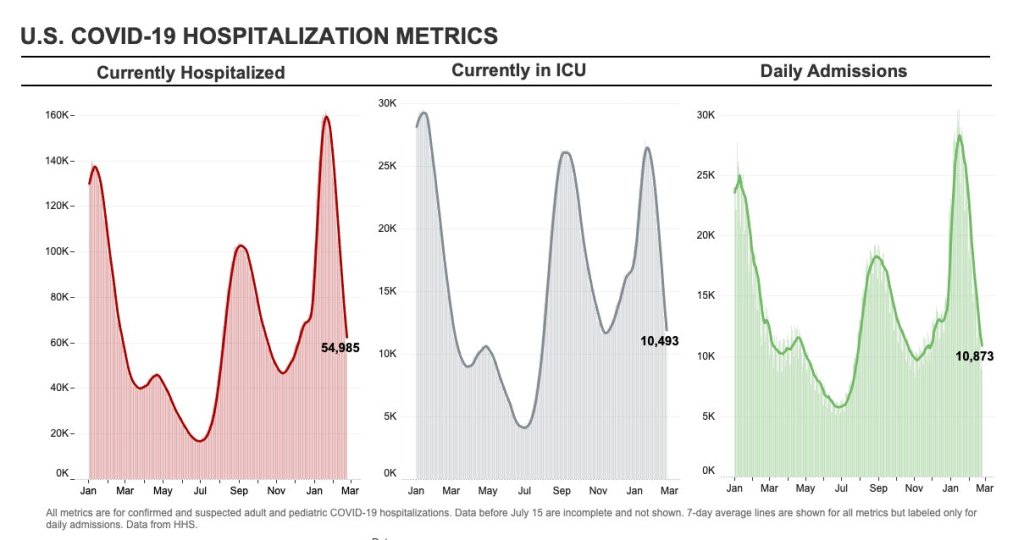

Instead, the CDC is focusing on hospitalizations: specifically, new COVID-19 admissions per 100,000 people and the share of inpatient beds occupied by COVID-19 patients. New hospital admissions are a more reliable—and more timely—metric than the total number of patients hospitalized with COVID-19, because admissions reflect only the people coming in with symptoms that recently started, not the people who have been hospitalized for days or weeks.

The share of inpatient beds occupied by COVID-19 patients, meanwhile, reflects the strain that this disease is currently putting on a hospital system. The CDC is choosing to include all COVID-19 patients here, not only those who are hospitalized for COVID-specific symptoms (the correct choice, in my view). Agency director Dr. Rochelle Walensky gave a good explanation for this at a media briefing on Friday:

We are considering anybody in a hospital bed with COVID, regardless of the reason for admission, and the reason that we landed there is multifold. First, many jurisdictions can’t differentiate, so that was important for us to recognize and realize. Second, whether or not a patient is admitted with COVID or for COVID, they increase the hospital capacity and they’re resource intensive. They require an isolation bed. They require PPE. They probably require a higher staff ratio. And so they are more resource intensive and they do take a COVID bed potentially from someone else.

Interestingly, as well, as we have less and less COVID in certain communities, the amount of people who are coming into the hospital with COVID will necessarily decrease. We will not have as many people walking around asymptomatically because there will just be less disease out there. So increasingly, as we have less disease in the community, we anticipate that more of the people who are coming into the hospital are going to be coming in because of COVID.

And then finally, as we have even less disease in the community, we anticipate that not every hospital is going to screen every patient for COVID as they walk in the door, especially if we have less and less disease in the community. And when that happens, we won’t actually be able to differentiate. In fact, people who are coming in, who are tested will necessarily be coming in for COVID. So for all of those reasons, comprehensively, we decided to stay with anybody coming in with a COVID diagnosis.

Also, a note on wastewater: I’ve seen some commentators express surprise that the CDC didn’t include wastewater in its new guidance, as this sewage surveillance can be a useful leading indicator for COVID-19 that’s more reliable than cases. The problem here is, wastewater surveillance is not available in much of the country—just look at all the empty space on this map. To use wastewater for decisionmaking, a county or state needs to have enough wastewater collection sites actually collecting these data, and most states are not there yet.

Critiques of the new guidance

While hospitalizations are a more reliable COVID-19 metric than cases, especially in our rapid testing era, they come with a few major issues. First, hospitalizations are a lagging indicator, meaning that they start to rise a couple of weeks after a new surge has started. If we rely on hospitalizations as a signal to put mask requirements or other safety measures in place, those changes will come weeks delayed.

As Boston University epidemiologist Dr. Ellie Murray put it in a recent Twitter thread: “Using lagging indicators like hospitalizations could be okay for turning *off* precautions IF we are sure that no new surge has begun. But that means we need leading indicators, like infection surveillance to guide turning *on* precautions.”

Another issue with relying heavily on this lagging indicator is, new COVID-19 safety measures may come too late to protect essential workers, children in schools, and others who face high risk of coronavirus exposure. “These high exposure populations get COVID first and most,” writes health policy expert Julia Raifman.

In other words, by the time case and hospitalization rates are high enough for a community to institute new safety measures under this new CDC guidance, those high-risk people are likely to be the ones already in the hospital. Raifman points to data from the U.S. Census’ Household Pulse Survey, showing that low-income workers were most likely to miss work for COVID-19 throughout last year.

Beyond this lagging indicator issue, another challenge with relying on hospitalizations is that, for many Americans, the hospitals that they might go to if they come down with severe COVID-19 are not located in their county. Plenty of counties, particularly in rural areas, don’t have hospitals! To deal with this, the CDC is actually using regional hospitalization figures, compiling statistics from multiple counties that rely on the same healthcare facilities.

University of South Florida epidemiologist Jason Salemi lays out this calculation in an excellent Twitter thread, linked below. While it makes sense that the CDC would need to use regional instead of local figures here, the agency is being pretty misleading by labeling this new guidance as county-level metrics when really, the metrics are not that localized.

There are more equity concerns embedded in the new CDC guidance as well. For counties with “low” or “medium” community COVID-19 levels, the CDC recommends that most Americans do not need to wear masks in public. But people who are immunocompromised or at high risk for severe disease should “talk to a healthcare provider” about the potential need to wear a mask indoors, stock up on rapid tests, or consider COVID-19 treatments.

For one thing, telling people, “talk to your doctor” is not a great public health strategy when one in four Americans do not have a primary care physician, and one in ten do not even have health insurance! For another thing, one-way masking among immunocompromised and otherwise high-risk people is also not a great strategy, because masks protect the people around a mask-wearer more than they protect the mask-wearer themselves. (I recommend this recent Slate piece on one-way masking for more on this topic.)

It is also pretty unclear how the CDC landed on a case threshold for “low transmission” that is much higher in this new guidance than in the old guidance, as Dr. Katelyn Jetelina points out in a recent Your Local Epidemiologist post. If anything, honestly, I would expect that the CDC needs to lower its case threshold, given that current case numbers are not accounting for millions of rapid tests done across the country.

Finally, the new CDC guidance completely fails to account for Long COVID. Of course, it would be very difficult for the CDC to do this, since the U.S. basically isn’t tracking Long COVID in any comprehensive way. Still, overly focusing this new guidance on hospitalizations essentially ignores the fact that a “mild” COVID-19 case which does not lead to hospitalization can still cause major, long-term damage.

Which metrics you should follow right now

Here are my recommendations of COVID-19 metrics to watch in your area as you navigate risk in this confusing pandemic era.

- Both the old and new CDC thresholds. While the CDC pushes its new guidance with a brand-new page on CDC.gov, community transmission metrics calculated under the old guidance are still available on the CDC’s COVID-19 dashboard. If you’re not feeling comfortable taking off your mask in public and want to wait until transmission is seriously low in your area, you can look at the old thresholds; though keep in mind that case data are seriously unreliable these days, for the reasons I explained above.

- Remember that masks are useful beyond COVID-19. Not a metric, but an additional note about thinking through risk: masks reduce risk of infection for a lot of respiratory diseases! We had a record-low flu season last winter and many Americans have avoided colds for much of the pandemic, thanks in part to masking. Helen Branswell has a great article in STAT News that unpacks this further.

- Wastewater data, if available to you. As I mentioned above, wastewater surveillance data are not available in much of the country. But if you live somewhere that this surveillance is happening, I highly recommend keeping an eye on those trends to watch for early warnings of future surges. You can look at the CDC dashboard or Biobot’s dashboard to see if your county is reporting wastewater data.

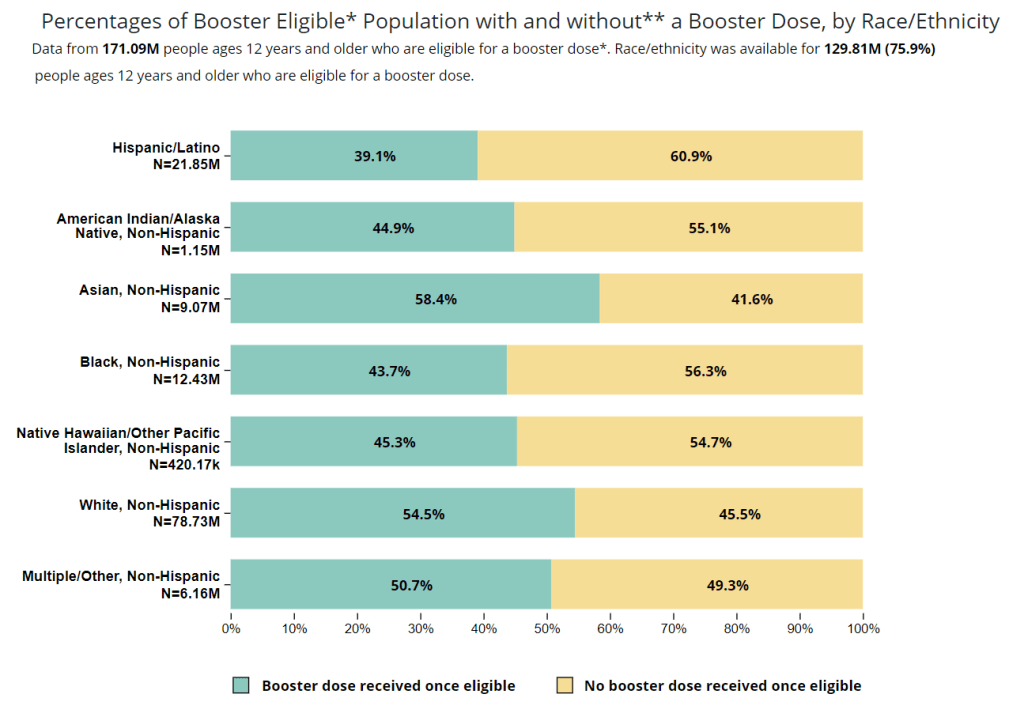

- Vaccination levels. It makes sense that vaccination was not included in the CDC guidance, because vaccinated people can still spread highly contagious variants like Omicron. Still, more highly-vaccinated counties—particularly those with high vaccination rates for seniors—are likely to have less burden on their healthcare systems when a surge arises, so knowing the vaccination rate in your county can still be useful when thinking about your risk tolerance.

- Rapid test availability. This is a bit more anecdotal rather than an actual data source, but: looking at rapid test availability in your local pharmacies may be another way to get a sense of community transmission in your area. Right now, these tests are easy to find in many places as case numbers drop; if finding these tests becomes more competitive again, it could be a signal that more people are getting sick or having exposures.

As always, if you have any questions or topics that you’d like me to tackle in this area, please reach out.