It’s been a somewhat slower week for COVID-19 news, so here’s something a little different: a reflection on a very old episode of Star Trek, in the context of post-viral illness.

Star Trek: Strange New Worlds, one of the new shows airing on Paramount+, has got me on a bit of a kick for the franchise. So, I’ve been rewatching The Original Series (TOS), which was one of my favorite TV shows in high school. (My girlfriend, who hasn’t seen any of the old Star Trek shows, has humored me by watching with me.)

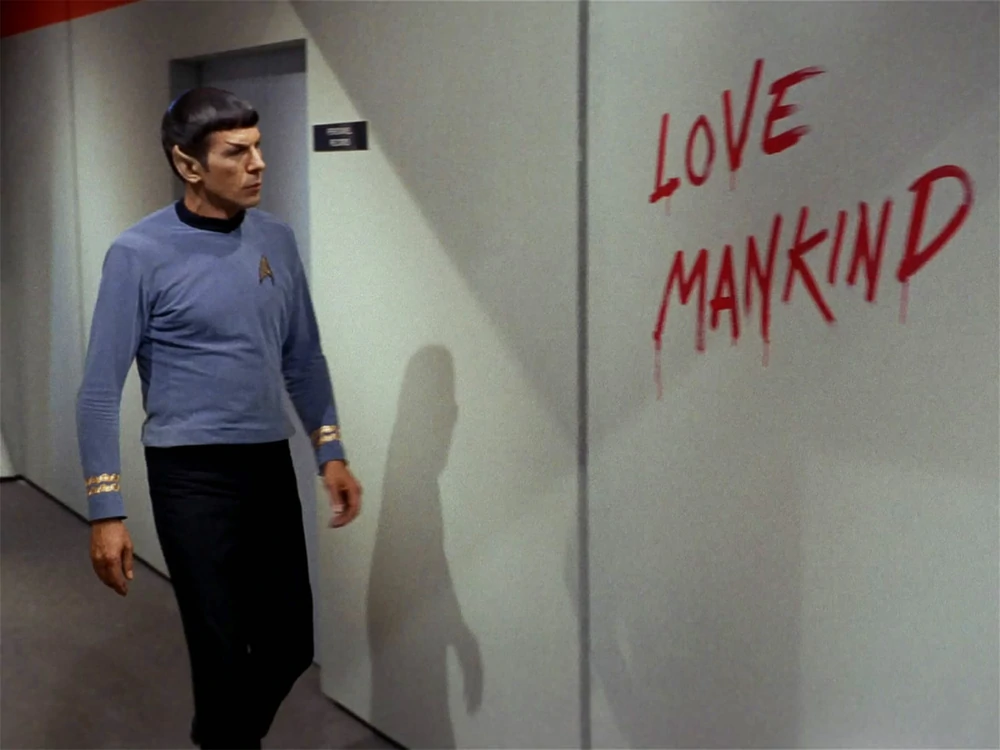

Last week, we watched an episode I remembered as one of my favorites: The Naked Time, episode four in the first season. In this episode—which first aired in September 1966—a strange virus from an alien planet gets onto the Enterprise and infects a number of crew members. Once infected, crew members lose their inhibitions and behave as though emotionally naked; this leads to such iconic scenes as Spock “sobbing mathematically,” Sulu chasing his colleagues with a rapier, Uhura saying she’s neither fair nor a maiden, and so on.

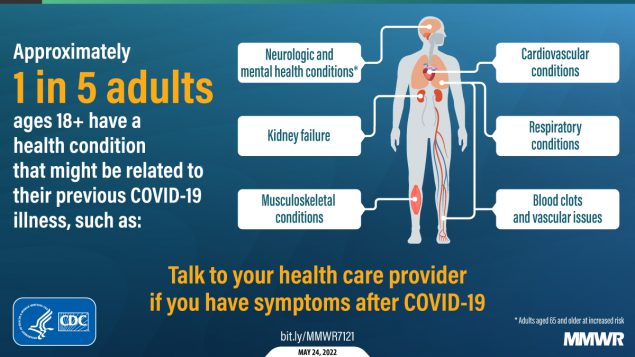

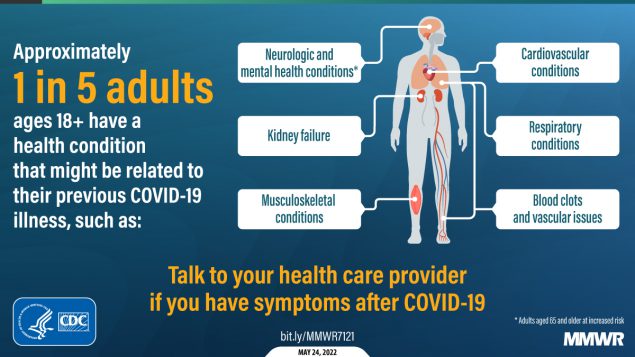

Rewatching this episode two years into the pandemic, it struck me that Star Trek predicted—like it predicted iPads, cellphones, and so many other things—neurological symptoms triggered by a viral infection. While the Epstein-Barr virus was discovered in 1964, it would be decades before scientists understood how viruses like this one could cause fatigue, chronic pain, post-exertional malaise, and other similar symptoms.

Now, of course, the world is facing an epidemic of Long COVID, the most prevalent post-viral illness in history. Recent estimates from the U.K.’s Office for National Statistics suggest that two million people—or, 3% of the entire U.K. population—are living with Long COVID. And Long COVID is bringing renewed attention to other conditions like ME/CFS and dysautonomia, which have a lot of symptom overlap. It’s hard to deny that infectious diseases can have ramifications far beyond what we usually expect from a cold or the flu.

My girlfriend, who previously hadn’t seen most of TOS, has commented on how much early Star Trek episodes center around psychological dilemmas. Rather than watching phaser battles, we’re watching characters grapple with questions like, “How do you stop a hormonal teenager with infinite power?” and, “What would happen if Captain Kirk were split into good and evil halves?”

The Naked Time fits into this pattern, but it also feels more like a horror story than the others—especially when one watches it in the midst of a COVID-19 (and Long COVID) surge. Star Trek’s writers guessed, nearly 60 years ago, that an infectious disease could impact people’s minds. But here we are in 2022: Long COVID patients are still systematically discredited by doctors, unable to access treatment and financial support, and discarded by American leaders’ decision to “live with the virus.”

The episode also offers some lessons in infection control measures by showing us what not to do when confronted with a novel illness. The alien virus gets onto the Enterprise in the first place because a crew member, investigating dead scientists on an abandoned planet, takes off his hazmat suit to touch his face; without realizing it, he transmits the virus from an infected surface to his skin. And after this index case starts acting strangely on the ship, other crew members don’t isolate him until it’s too late. Funny how our basic public health measures haven’t changed since the 60s, either.

Anyway, because this is Star Trek, Dr. McCoy saves the day by quickly developing a cure for the virus. He has no trouble administering it to the crew—there’s no vaccine hesitancy on the Enterprise.

Still, this episode sticks with me, more now than when I first watched it years ago. With all the new technology we have now to fight COVID-19, the basic measures we can take to control a novel virus haven’t changed. And the stakes are higher than ever.