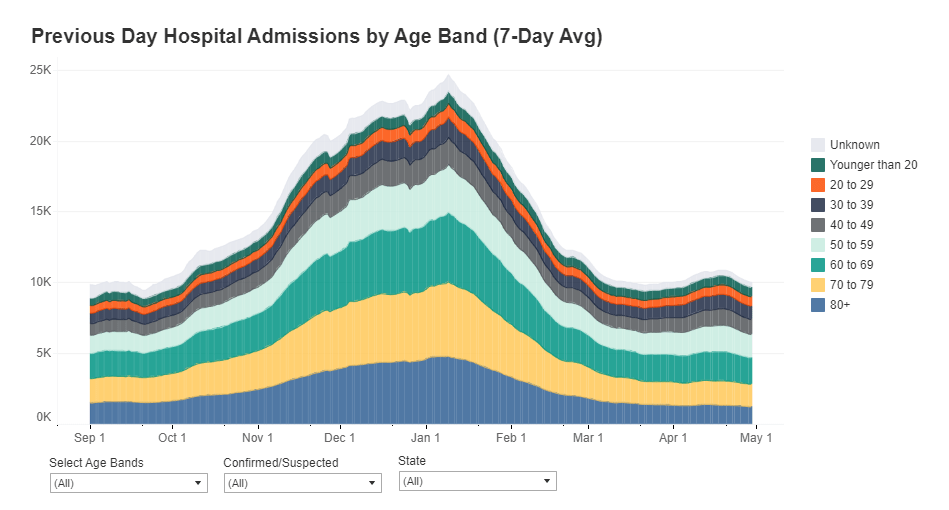

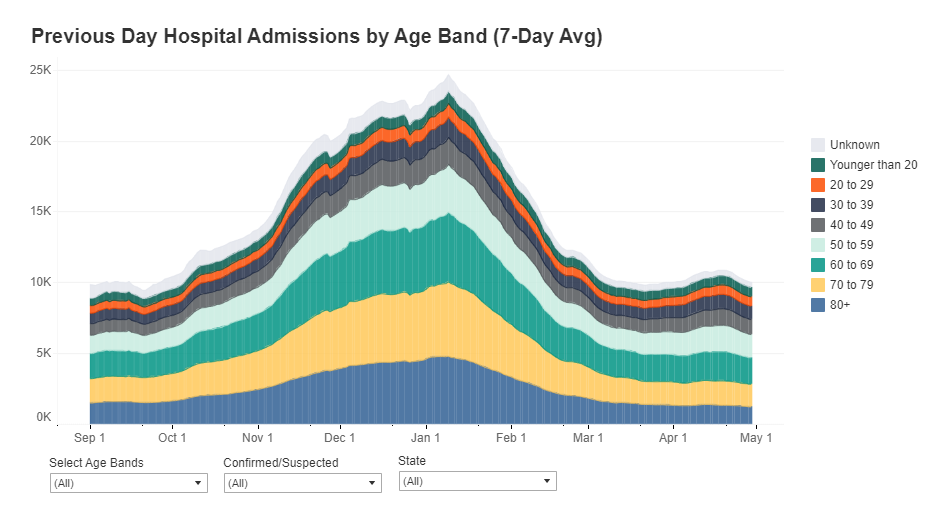

A record number of COVID-19 patients are now receiving care in U.S. hospitals, according to data from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). As of January 16, the agency reports that about 157,000 COVID-19 patients are currently hospitalized nationwide, and one in every five hospitalized Americans has been diagnosed with this disease.

The HHS also reports that about 78% of staffed hospital beds and 82% of ICU beds are currently occupied. These numbers, like the total COVID-19 patient figure, are higher than they have been at any other point during the pandemic.

Even so, reports from the doctors and other staff working in these hospitals—conveyed in the news and on social media—suggest that the HHS data don’t capture the current crisis. The federal data may be reported with delays and fail to capture the impact of staffing shortages, obscuring the fact that many regions and individual hospitals are currently operating at 100% capacity.

Dr. Jeremy Faust, an emergency physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor at Harvard Medical School, recently made this argument in Inside Medicine, his Bulletin newsletter. Last week, I shared Faust and colleagues’ circuit breaker dashboard, which extrapolates from both federal hospitalization figures and current case data to model hospital capacity in close-to-real-time. This week, Faust used that dashboard to show that the crisis inside hospitals is more dire than HHS numbers suggest.

He writes:

There seems to be a disconnect between the official data made available to the public and what’s happening on the ground. The reason for this is unacceptable delays in reporting. HHS and other agencies have always acknowledged that public reports on hospital capacity—for Covid-19 and all other conditions—actually reflect data that are 1-2 weeks old. But until now, such lags rarely mattered because most hospitals haven’t had to operate near or above 100% capacity routinely, even during the pandemic. Under normal circumstances, whether a hospital was 65% or 75% full does not make much of a difference, though as the numbers creep up, care can be compromised. And even in past moments when capacity was closer to 100%, a wave of Omicron-driven Covid-19 was not headed towards hospitals.

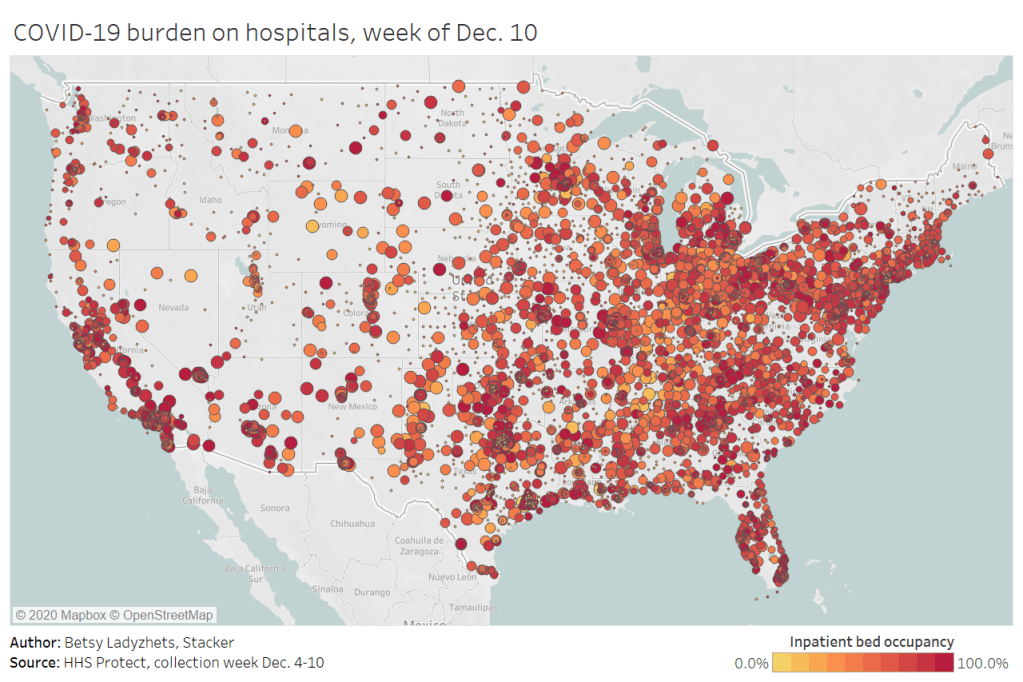

For example: on Monday, Faust wrote, his team’s circuit breaker dashboard showed that “every single county in Maryland appears to be over 100% capacity,” even though the HHS said that 87% of hospital beds were occupied in the state. Healthcare workers in Maryland backed up the claim that all counties were over 100% capacity, with personal accounts of higher-than-ever cases and hospitals going into crisis standards.

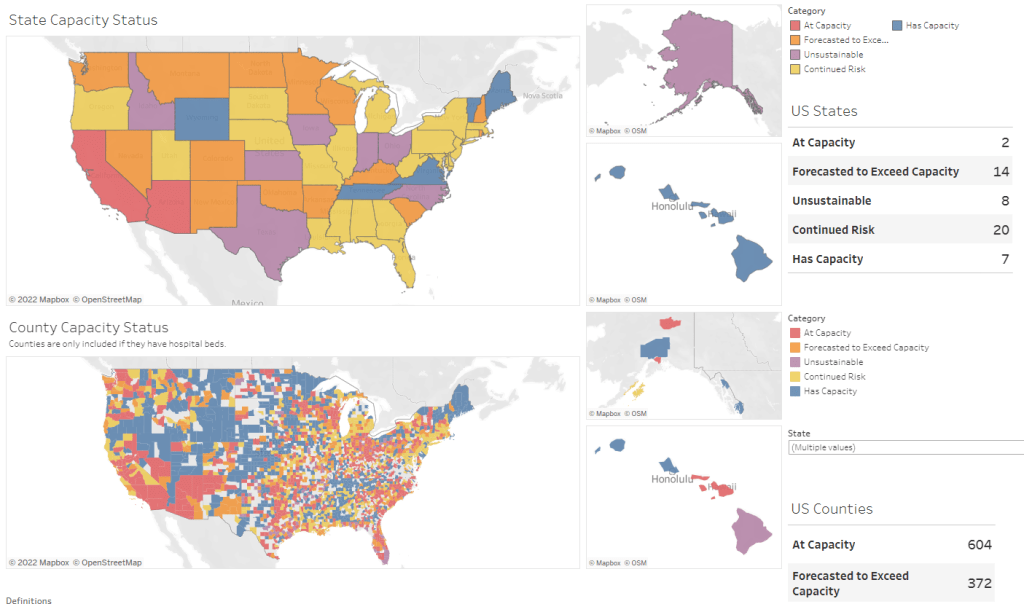

On Thursday, Faust shared an update: the circuit breaker dashboard, at that point, projected that hospitals in Arizona, California, Washington, and Wisconsin were approaching 100% capacity, if they weren’t at that point already. As of Saturday, California and Arizona are still projected to be at “at capacity,” according to the dashboard, while 14 other states ranging from Montana to South Carolina are “forecasted to exceed capacity” in coming days.

var divElement = document.getElementById(‘viz1642354079303’); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName(‘object’)[0]; if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 800 ) { vizElement.style.minWidth=’1087px’;vizElement.style.maxWidth=’100%’;vizElement.style.minHeight=’1736px’;vizElement.style.maxHeight=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+’px’;} else if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 500 ) { vizElement.style.minWidth=’1087px’;vizElement.style.maxWidth=’100%’;vizElement.style.minHeight=’1736px’;vizElement.style.maxHeight=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+’px’;} else { vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.height=’3027px’;} var scriptElement = document.createElement(‘script’); scriptElement.src = ‘https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js’; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);From Faust’s descriptions and the accounts of healthcare workers he quotes, it’s also evident that determining between hospitalizations “with” COVID-19 and hospitalizations “from” COVID-19 is not a useful way to spend time and resources right now. Even if some of the COVID-19 patients currently in U.S. hospitals “happened to test positive” while seeking treatment for some other condition, these patients are still contributing to the intense pressure our healthcare system is under right now.

Plus, as Ed Yong explains in a recent article in The Atlantic describing this false patient divide, COVID-19 can worsen other conditions that at first seem unrelated:

The problem with splitting people into these two rough categories is that a lot of patients, including those with chronic illnesses, don’t fit neatly into either. COVID isn’t just a respiratory disease; it also affects other organ systems. It can make a weak heart beat erratically, turn a manageable case of diabetes into a severe one, or weaken a frail person to the point where they fall and break something. “If you’re on the margin of coming into the hospital, COVID tips you over,” Vineet Arora, a hospitalist at the University of Chicago Medicine, told me. In such cases, COVID might not be listed as a reason for admission, but the patient wouldn’t have been admitted were it not for COVID.

In short: Omicron might be a milder variant at the individual level—thanks to a combination of the variant’s inherent biology and protection from vaccines and prior infections—but at a systemic level, it’s devastating. And rather than asking hospitals to split their patients into “with” versus “from” numbers, we should be giving them the staff, supplies, and other support they need to get through this crisis.