In the past week (November 24 through 30), the U.S. reported about 303,000 new COVID-19 cases, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 43,000 new cases each day

- 92 total new cases for every 100,000 Americans

- 1% fewer new cases than last week (November 17-23)

In the past week, the U.S. also reported about 29,000 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals. This amounts to:

- An average of 4,200 new admissions each day

- 9.0 total admissions for every 100,000 Americans

- 18% more new admissions than last week

Additionally, the U.S. reported:

- 1,800 new COVID-19 deaths (250 per day)

- 63% of new cases are caused by Omicron BQ.1 and BQ.1.1; 6% by BF.7; 5% by BN.1; 6% by XBB (as of December 3)

- An average of 200,000 vaccinations per day

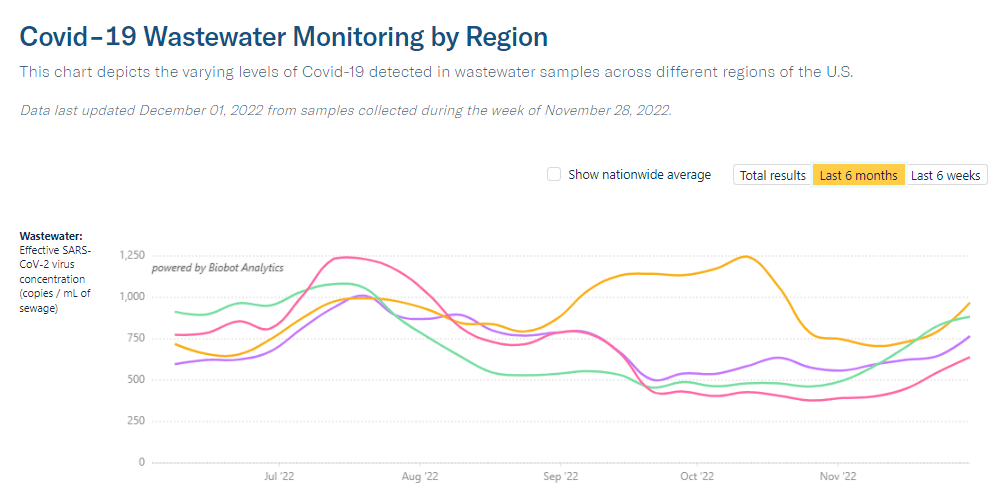

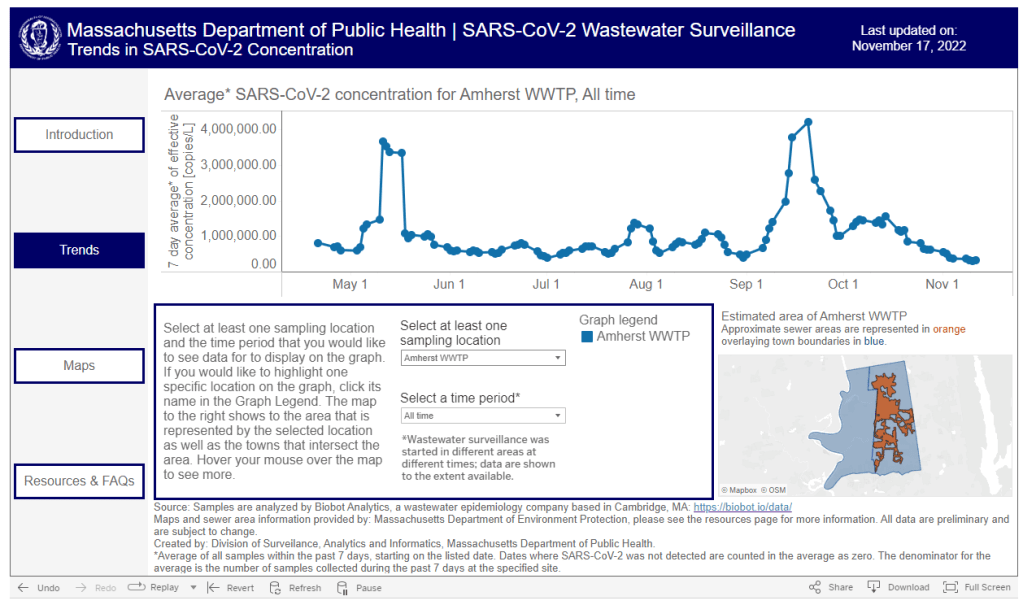

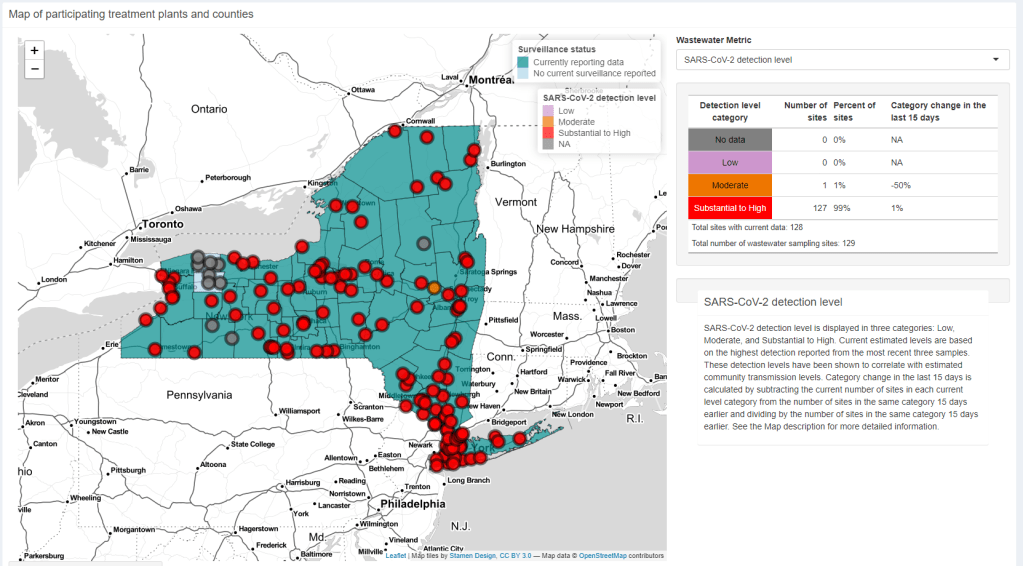

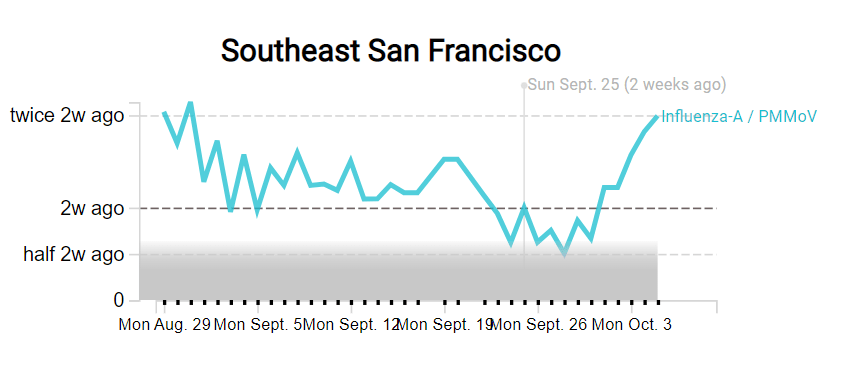

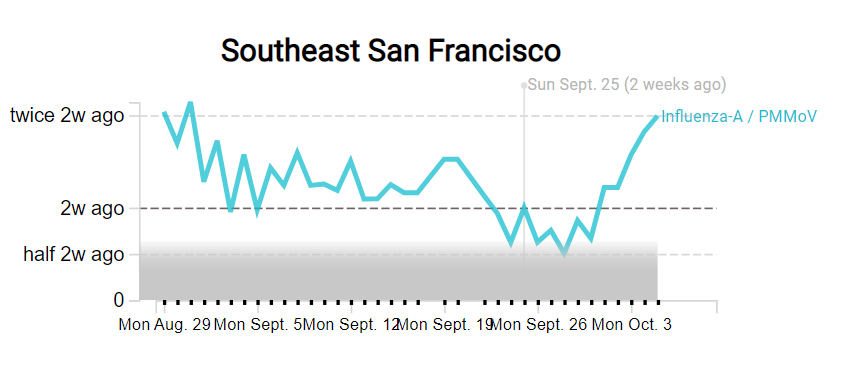

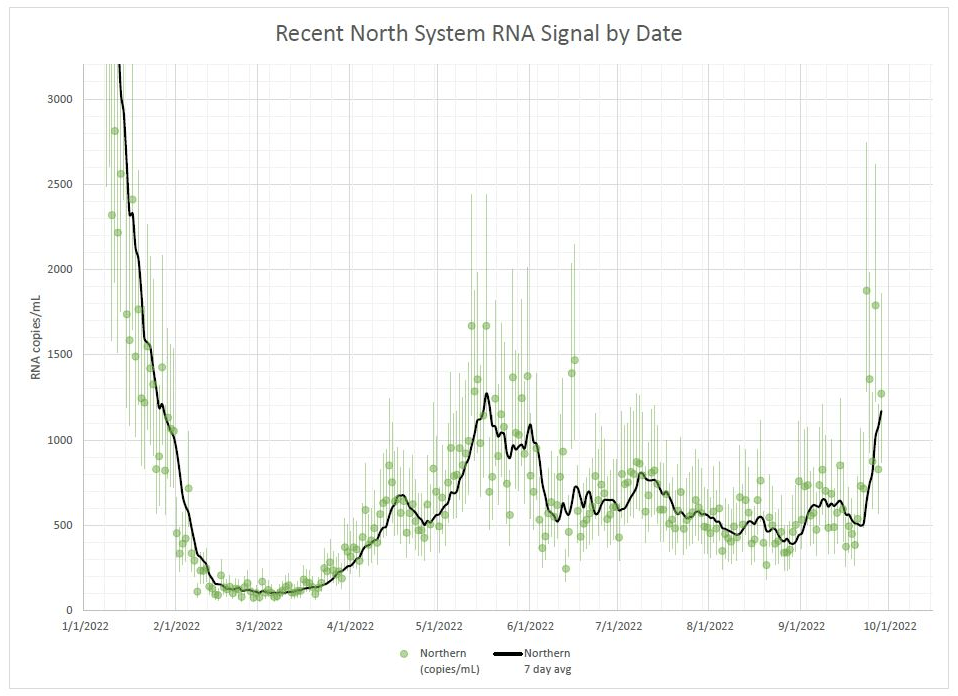

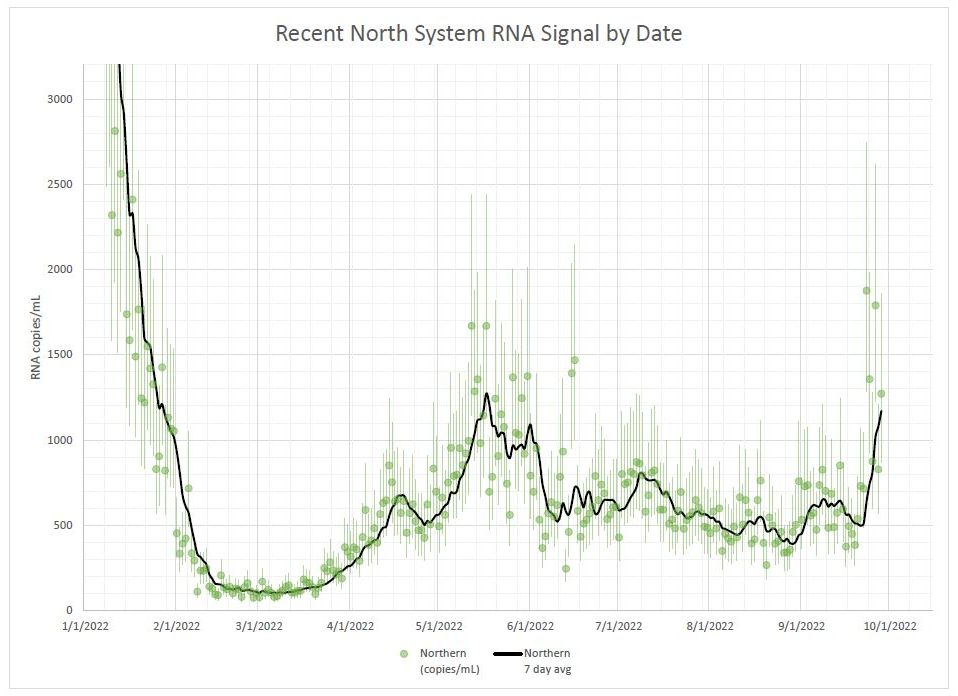

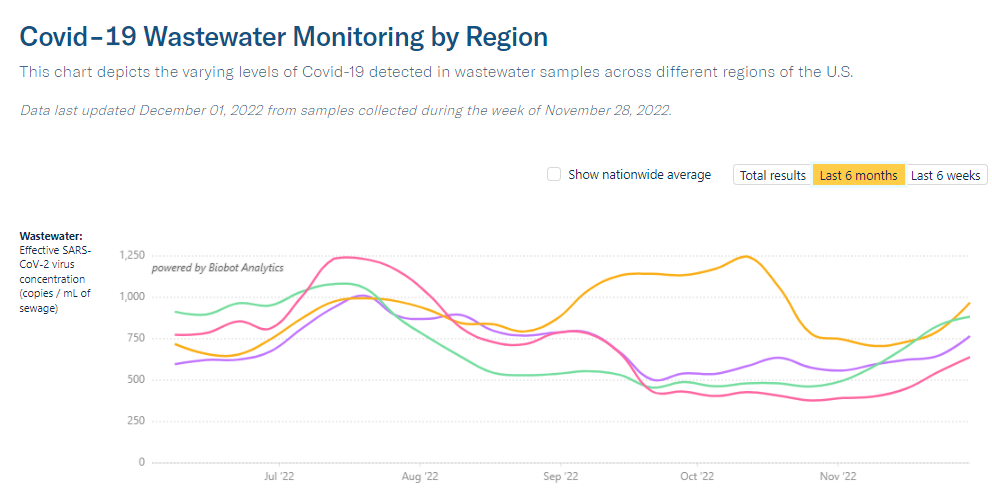

If the U.S. wasn’t at the start of a COVID-19 surge before Thanksgiving, we’re certainly in one now. While official case counts have stagnated, wastewater surveillance indicates that the country is seeing about 1.5 times the coronavirus transmission that we had three weeks ago, according to data from Biobot.

All four major regions of the country are experiencing clear upward trends in COVID-19 spread, per Biobot, with no sign of peaking; this is the first time there’s been a unified national increase since mid-summer. Individual metropolitan areas from Boston, to the Twin Cities in Minnesota, to Los Angeles, are reporting major upticks.

The current difference between wastewater surveillance trends and case trends further confirms what I’ve been saying for months: case data simply are no longer that helpful for seeing early warnings of surges, as few people seek out PCR testing compared to earlier points in the pandemic. If you don’t already have a good place to see wastewater data for your community, put some pressure on your local officials to make this information available.

The U.S.’s new increase in transmission can likely be attributed to travel and gatherings over the Thanksgiving holiday, combined with newer, more-transmissible versions of Omicron. Lineages BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 caused almost two-thirds of new cases in the week ending December 3, according to CDC estimates, while XBB caused about 6% of new cases.

XBB has been spreading intensely in some Asian countries, and experts are watching to see how it competes with the alphabet soup of subvariants already circulating in the U.S. So far, it is most prevalent in the Northeast, per the CDC.

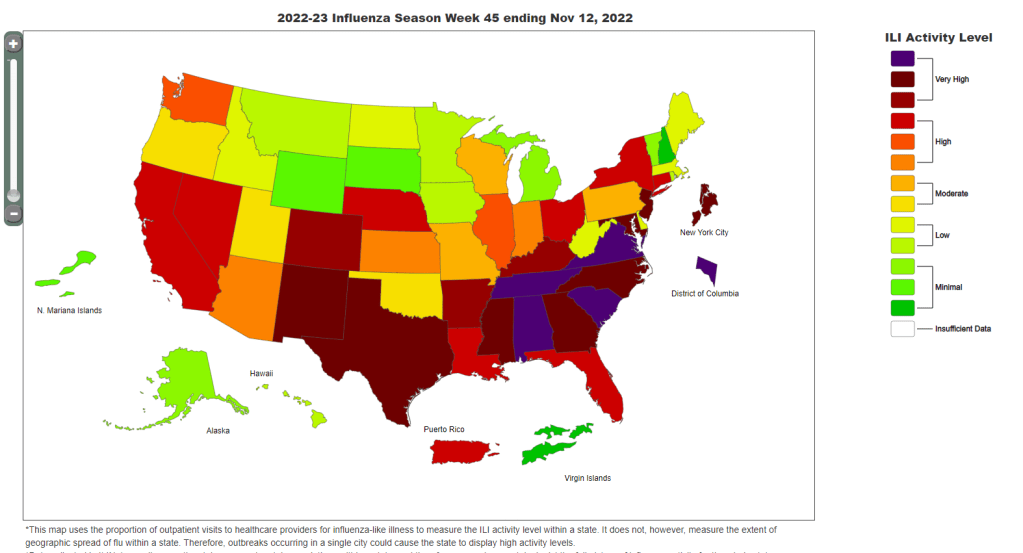

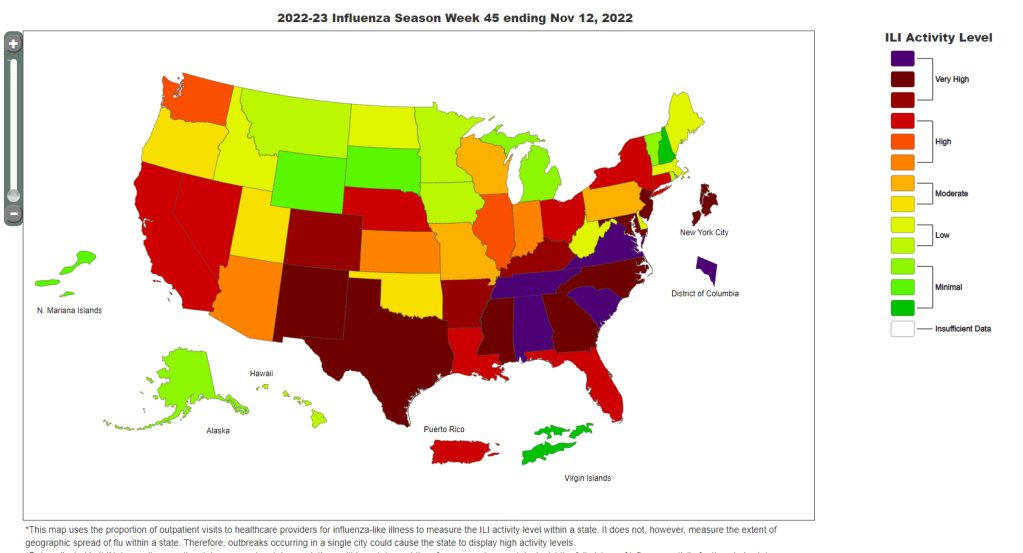

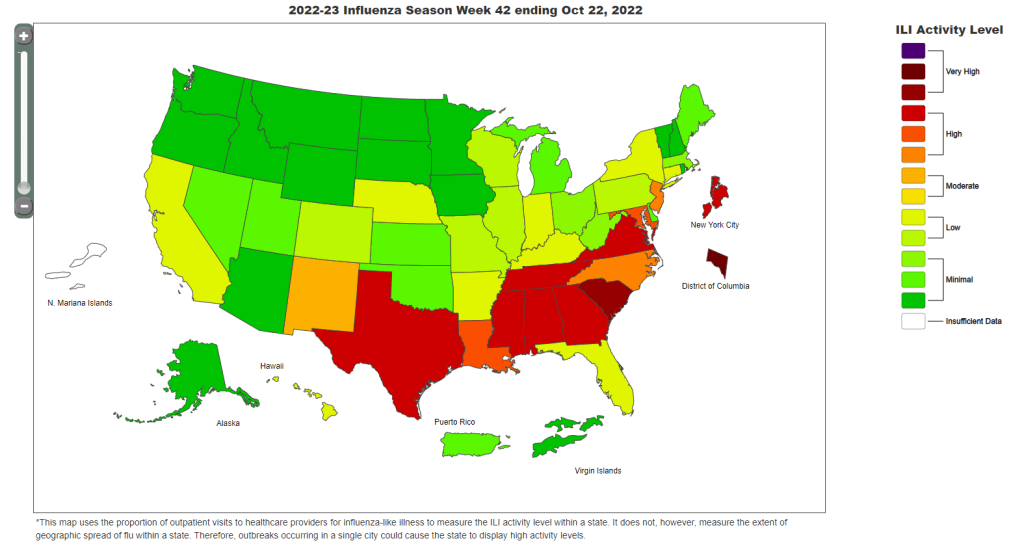

In addition to wastewater trends, new hospital admissions for COVID-19 went up this week: about 18% more patients were admitted to hospitals around the country in the week ending November 30 compared to the prior week. These patients are entering a hospital system already overwhelmed by flu, RSV, and other respiratory viruses.

As epidemiologist Caitlin Rivers noted in her newsletter last week: “The cumulative hospitalization rate for influenza is already on par with where we would expect to be in December or January.” And that virus continues to spread further, with most of the country experiencing high or very high levels of influenza-like activity.

COVID-19 and these other viruses might not seem like a big deal thanks to vaccines and treatments, but they can still have very severe consequences. For example, New York City just reported that three children died of COVID-19 in recent weeks. And the risk of Long COVID remains, too.