It’s now been a couple of weeks since updated COVID-19 vaccines became available in the U.S. At this point in prior COVID-19 vaccine rollouts, we would know a lot about who had received those vaccines: data would be available by state, for different age groups, and other demographic categories.

This time, though, the data are missing on a national scale. Following the end of the federal public health emergency in May, the CDC has lost its authority to collect vaccination data from all state and local health agencies that keep immunization records. As a result, the CDC is no longer providing comprehensive vaccination numbers on its COVID-19 dashboards.

But we still have some information about this year’s vaccination campaign, thanks to continued CDC efforts as well as reporting by other health agencies and research organizations. In fact, last week, the federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) told reporters that more than seven million Americans have received updated COVID-19 vaccines so far this fall.

HHS also said that about 14 million doses have been shipped to vaccination sites, primarily pharmacies. In addition, 710,000 vaccines for children have been ordered through a federal program that provides these shots.

Vaccine distribution numbers are slightly easier for the CDC and HHS to collect, as they can work directly with vaccine manufacturers. To understand how many people are getting the shots, though, is more challenging—requiring a mix of data from state and local agencies, surveys, and other surveillance mechanisms.

What changed with the PHE’s end:

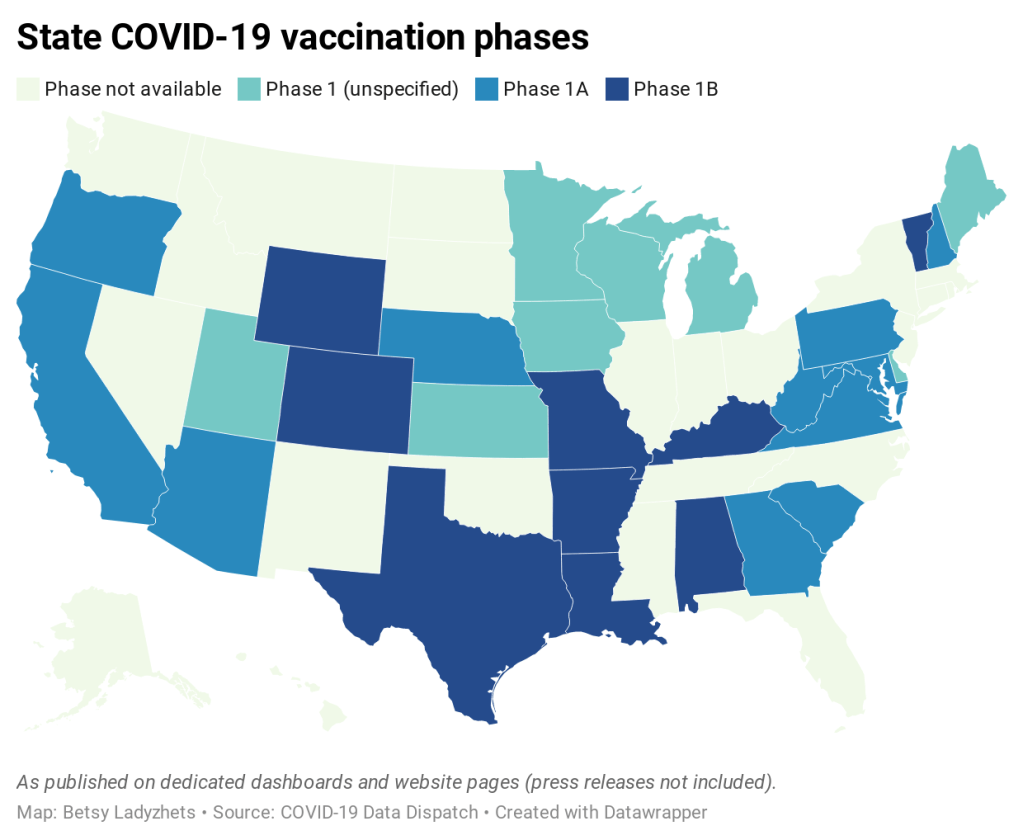

Early in the pandemic, the CDC established data-sharing agreements with the health agencies that keep immunization records. This includes all states, territories, and a few large cities (such as New York City and Philadelphia) that have separate records systems from their states; you can see a full list of records systems here.

Through those agreements, the CDC collected vaccine administration numbers, standardized the data (as much as possible), and reported them on public dashboards. The CDC wasn’t able to collect as detailed demographic information as many health experts would’ve liked—for example, they never reported vaccinations by race and ethnicity below the national level. But the data were still useful for tracking who got vaccinated across the U.S.

These data-sharing agreements concluded with the end of the public health emergency (PHE) in May 2023. According to a CDC report published at that time, the CDC was able to extend agreements with some jurisdictions past the PHE’s end. Still, the report’s authors acknowledged that “future data might not be as complete” as during the emergency period. Even if 40 out of 50 states keep reporting, the remaining 10 represent data gaps.

Notably, the May report also claims that the CDC would continue to provide data on COVID-19 vaccination coverage on the CDC’s COVID-19 dashboard and a separate vaccination dashboard. But neither of those dashboards has been updated with any information from this fall’s vaccine campaign, as of this publication.

In addition to compiling data from state and local systems, the CDC has other mechanisms for tracking vaccinations. According to CBS News reporter Alexander Tin, CDC officials highlighted a couple during a briefing on October 4:

- The National Immunization Survey, a phone survey conducted by CDC officials to estimate national vaccination coverage based on a representative sample of Americans. This survey is currently the CDC’s method for tracking flu vaccinations.

- CDC’s Bridge Access and Vaccines for Children (VFC) programs, both of which buy vaccines to distribute to Americans who may not have health insurance or face other financial barriers to vaccination. The Bridge Access program was specifically set up for COVID-19 vaccines, while the VFC program covers other childhood vaccines.

- Contact with vaccine manufacturers and distributors, i.e. the pharmaceutical companies that make the vaccines and the pharmacies and healthcare organizations that give them out. These companies share data with the CDC, offering insights into how many vaccines have been distributed to different locations; though the data may not be comprehensive if not all distributors are included (i.e. just big pharmacy chains, not smaller, independent stores).

Other places to look for vaccination data:

Outside of the CDC, there are a few other places where you can look for vaccination data. Here are a couple that I’m monitoring:

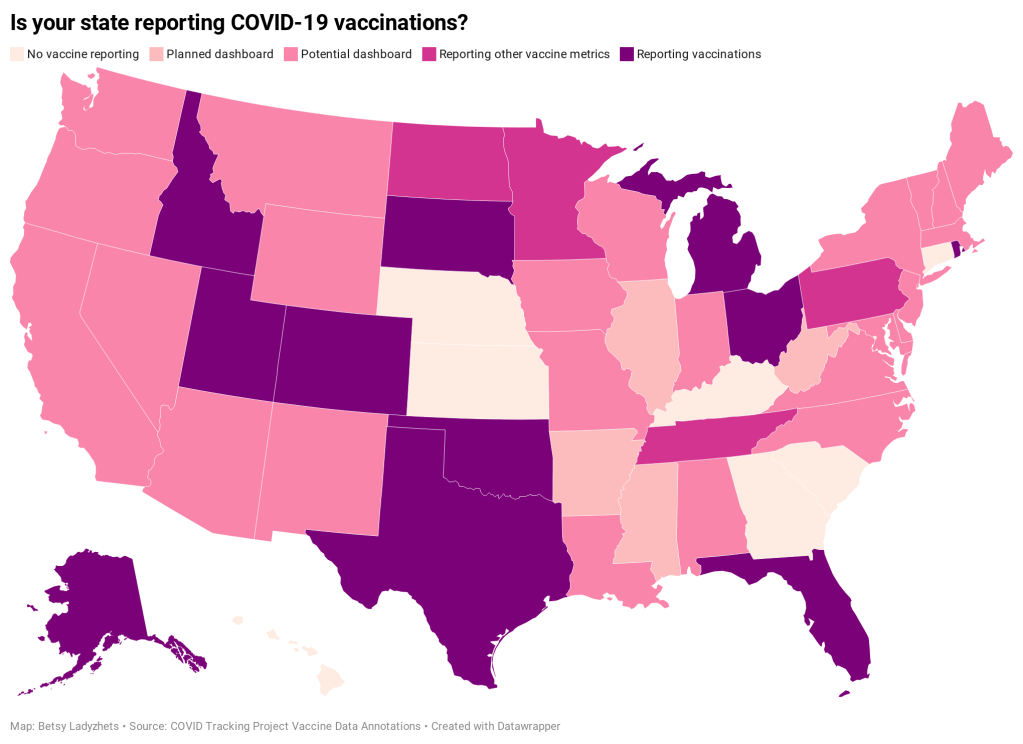

- State and local public health agencies: Some agencies that track immunizations have their own dashboards, reporting on vaccinations in a specific state or locality. For example, New York City’s health department tracks COVID-19 vaccinations among city residents, although the agency hasn’t yet published data for this fall’s vaccines. I have a list of state vaccination dashboards here; this doesn’t currently represent data on the fall 2023 vaccines, but I aim to do that update in the coming weeks.

- Outside surveys, such as KFF’s COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: Like the CDC’s National Immunization Survey, other health organizations conduct surveys to track vaccinations. The Kaiser Family Foundation’s COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor is one well-known project, which has been doing regular surveys on COVID-19 vaccine uptake since December 2020.

- Scientific reports answering specific vaccination questions: Public health researchers may use surveys, immunization records, or other data systems to study specific questions about vaccination, such as the impact that vaccination has on lowering a patient’s risk of severe disease. These studies are often published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report and other journals.

If you have other questions about vaccination data—or want to share a data source I didn’t mention here—please reach out: email me or leave a comment below.