It’s difficult to get good internet access in Garrett County, Maryland. The county lies in the Appalachian Mountains, full of peaks and ridges, trees and rivers. This geography blocks signals and slows internet speeds, even for Garrett County residents who do have a router at home. And the county’s southern edge meets the National Radio Quiet Zone, where cell and internet service is restricted in order to preserve data collection for West Virginia’s Green Bank Telescope.

Even Barbara Baker, superintendent of Garrett County Public Schools, has a hard time getting service: During her interview with the COVID-19 Data Dispatch, poor Zoom quality forced the conversation onto a phone call.

“Working from home, teaching from home, and learning from home was a huge hurdle for us to overcome,” Baker said.

Of course, such a wifi-challenged district is not cut out for virtual classes, making in-person school a priority. Unlike other districts in Maryland, Garrett County Public Schools was able to bring the majority of its students back to classrooms during the spring 2021 semester. The district built trust with its community by utilizing local partnerships, providing families with crucial supplies, setting up task forces to plan reopening, and communicating extensively with parents.

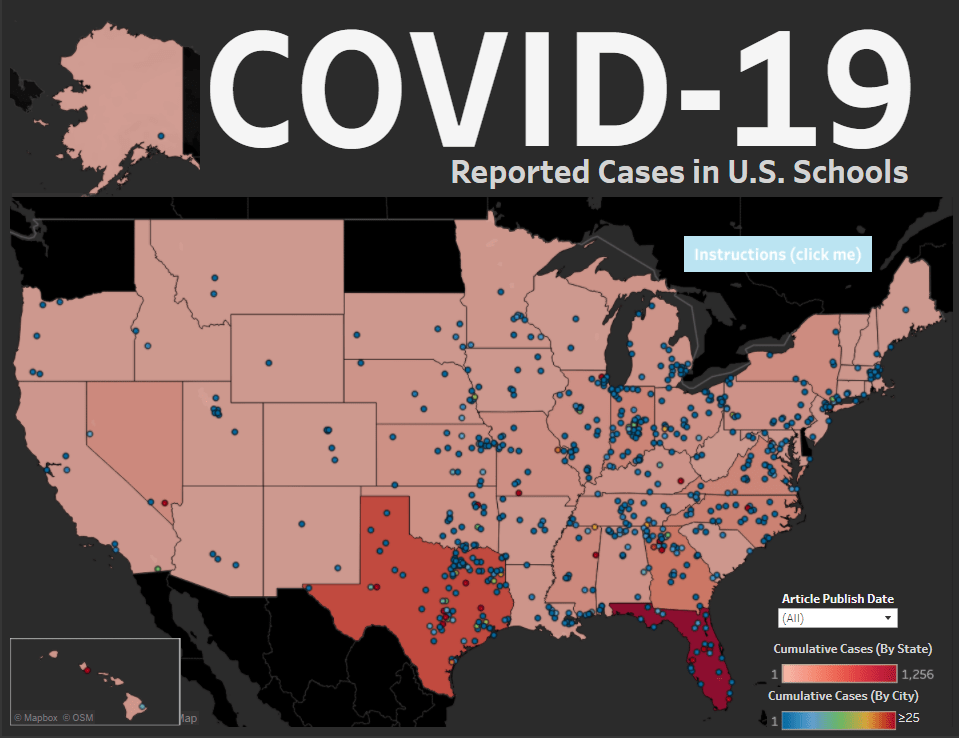

Garrett County’s school district is the subject of the second profile in the COVID-19 Data Dispatch’s “Opening” series. Alongside four other school communities, we selected it because the majority of the district’s students returned to in-person learning during the 2020-2021 school year — and officials identified COVID-19 cases in under 5% of the student population. (According to the CDC, about 5% of school-aged children in the U.S. have contracted COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic.)

Demographics for Garrett County, Maryland

Census population estimates, July 2019

- Population: 29,000

- Race: 96.2% white, 1.2% Hispanic/Latino, 1.1% Black, 1.0% two or more races, 0.4% Asian

- Education: 89.8% have high school degree, 20.9% have bachelor’s degree

- Income: $52,600 is median household income, 12.8% in poverty

- Computer: 84.6% have a computer, 76.9% have broadband internet

- Free lunch: 47.8% of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch1

COVID-19 stats for Garrett County Public Schools

- Total enrollment: 3,600 students2

- In-person enrollment: 86% after reopening for a four-day week in March2

- Total cases, 2020-2021 school year:

- 5 cases in the fall (identified by the state in two elementary school outbreaks)3

- 17 cases in the spring (15 rapid test positives, 2 PCR test positives); none identified by the state as outbreaks4

1Source: National Center for Education Statistics

2Source: Interview with Superintendent Barbara Baker

3Source: Maryland COVID-19 School Outbreaks dataset

4Source: Data from School Health Services Manager Rebecca Aiken

Spring 2020: Combatting remote challenges, in-person preparation

Due to wifi issues and a learning curve with the district’s online platform, in spring 2020, Garrett County families and educators struggled to access remote classes. But the district used this time to prepare for its eventual return by providing computers, tablets, and wifi hotspots resources to students and building trust for the next year.

The district used a federal grant to purchase about 1,000 wifi hotspots, which were both distributed to students and set up in central locations to which families could easily drive. At a total of 650 square miles, Garrett County is relatively large, and with under 50 people per square mile, its residents are fairly spaced out. Administrators aimed to set up hotspots in enough locations that nobody would need to drive more than ten miles to access wifi.

At the same time, district staff delivered meals to families. About half of Garrett County students are eligible for free lunch, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Scott Germain, the district’s food services supervisor, quickly pivoted from cafeteria meals to meals on the road. His team brought food from the district’s twelve schools to churches, community centers, and other central locations so that families could avoid traveling more than a few miles.

Like many other districts, Garrett County took advantage of federal grant money to improve ventilation and cleaning at school buildings. But unlike others, this district stands out for a unique, collaborative strategy used to plan its return to classrooms in fall 2020.

The district brought stakeholders together through “TIGER teams”, or “Targeted Immediate Group Execution and Response” teams. Each team was composed of people from varied backgrounds, all unified around a singular reopening-related goal, such as COVID-19 testing and learning connectivity. Teams typically included at least one parent, one community member, and one doctor, health department officer, or other relevant expert.

Similarly to Austin, Indiana, partnerships between the school district and the local public health department proved crucial in reopening. While school buildings were closed in spring 2020, the district’s nursing staff worked with the Garrett County public health department to run testing sites.

“We just became one agency, almost, for a while,” said School Health Services Manager Rebecca Aiken of the school’s nursing staff and the local health department. School nurses were able to expertly swab students who came to class with COVID-19 symptoms when classrooms opened up in the fall.

Fall 2020: Hybrid, then back to virtual

The fall 2020 semester started with a hybrid model, due to concerns about maintaining six-foot spacing between students in every classroom. Most students were coming in for two days in person, while Wednesday was reserved as a day where children worked remotely on their own, giving teachers extra prep time. A small number of students opted to stay all-remote and another small number, identified by the district as most likely to fall behind during remote learning, came in all four days. (Precise numbers are not available, but administrators estimate that 10% to 15% were in all four days during this time.)

During the hybrid period, the state of Maryland identified two small outbreaks at Garrett County schools. The state defines a classroom outbreak as at least two confirmed COVID-19 cases among teachers, students, and staff within a two-week period; cases must be epidemiologically linked but not within the same household. Maryland data reveal two cases at Route 40 Elementary School and three at Yough Glades Elementary School, from October to December.

Despite these relatively low case numbers, the hybrid model was short-lived: Rising cases in Maryland forced the district to return to virtual-only learning in November. Still, the district was better prepared this time. More students had computers and wifi, and teachers and families were familiar with the district’s online platform.

That return to remote made administrators even more determined to bring students back in the spring. In January, Maryland governor Larry Hogan ordered all school systems to bring kids back to at least hybrid instruction by March 1; this order “gave a little bit of teeth” to Garrett County school leadership, Superintendent Baker said.

Spring 2021: Communication and trust

By March 1, Garrett County students were back in classrooms four days a week. Wednesday remained an asynchronous preparation day for teachers, most of whom still had a small number of remote-only students in their classes.

Feedback from teachers informed that schedule, but the district also actively solicited — and responded to — feedback from parents. Administrators collected feedback through surveys, and principals made personal phone calls to check in on parents. Questions from parents were funneled into a detailed FAQ document on the district’s website; the document currently stands at 22 pages long and was, at times, updated multiple times a day.

“[Parents knew] we were listening, that we knew that they had questions and that we were trying to answer them to the best of our ability,” Baker said.

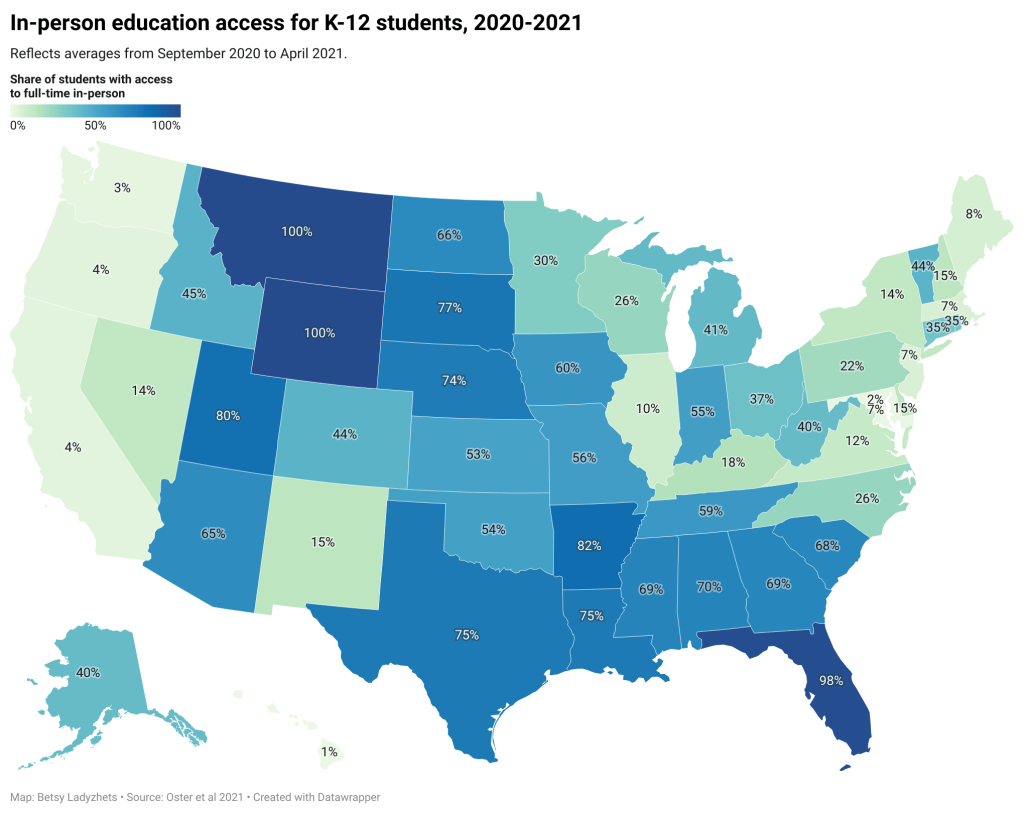

This detailed attention to parent feedback — combined with the trust built up by providing technology, food, and other services — may be one reason why Garrett County bucks Maryland’s overall trend in bringing students back to classrooms. According to a study published in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, over three-quarters of Maryland K-12 students only had access to fully remote learning during the 2020-2021 school year. In Garrett County, though one day remained remote, 86% of students returned to almost-full-time in-person learning by the end of the spring semester.

“I think it was a real testament to the fact that the families trusted that we would keep their children safe, that we would put the safety protocols into place,” Baker said.

Indeed, between late March and early May this year, only 17 students and staffers tested positive for COVID-19 in the schools, well under one percent of the district population. These numbers do not reflect all cases in the district, according to Aiken, head of school health services, because some students were not tested through the school. She said that all of these students were infected outside the school setting — at part-time jobs, social gatherings, and other community functions — and quick contact tracing through the local health department helped prevent spread at schools themselves.

On Sept. 7 this year, all Garrett County students will be back in the classroom, all five days a week. As the fall safety plan currently stands, masks are strongly recommended (though not required), but enhanced ventilation, three feet distancing, testing, and other protocols will continue. Additional precautions may be added before the school year starts, Chief Academic Officer Nicole Miller said in an email on August 18.

Principals prepared for the transition by once again calling parents to have one-on-one conversations about their concerns, with a focus on the families who chose remote learning last spring. The health services team prepared with vaccination clinics for students and staff; the vast majority of school staff (92% as of late July) are vaccinated already, thanks in part to similar clinics in the spring. Administrators also continue to update their FAQ document, solicit feedback, and build trust with their community — building connections where wireless internet networks have failed.

“We had the collaboration, and we had the connections, and we had the framework built before this happened,” Aiken said. “I think that’s what made [reopening] so successful.”

The COVID-19 Data Dispatch’s “Opening” series is available for other publications to republish, free of charge. If you or your outlet is interested in publishing any part of this series, please contact betsy@coviddatadispatch.com.