By Betsy Ladyzhets

In the COVID-19 Data Dispatch’s “Opening” series, we profiled five school communities that successfully reopened during the 2020-2021 school year. In each one, the majority of the district’s or school’s students returned to in-person learning by the end of the spring semester — and officials identified COVID-19 cases in under 5% of the student population.

Through exploring these success stories, we found that the schools used many similar strategies to build trust with their communities and keep COVID-19 case numbers down.

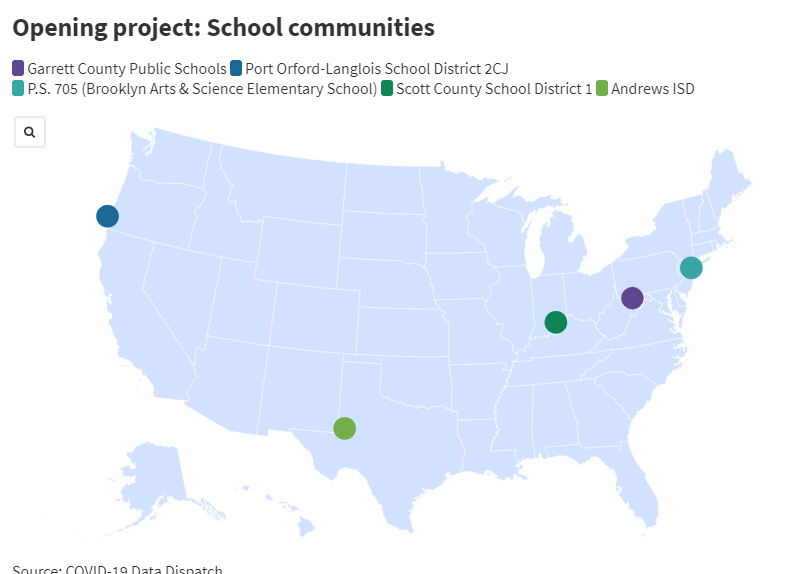

These are the five communities we profiled:

- Scott County School District 1 in Austin, Indiana: This small district faced a major HIV/AIDS outbreak in 2015, leading to an open line of communication between Austin’s county public health agency, school administrators, and other local leaders which fostered an environment of collaboration and trust during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Garrett County Public Schools in Maryland: In a rural, geographically spaced-out county, this district built trust with its community by utilizing local partnerships, providing families with crucial supplies, setting up task forces to plan reopening, and communicating extensively with parents.

- Andrews Independent School District in Texas: This West Texas district prioritized personal responsibility, giving families information to make individual choices about their children’s safety. Outdoor classes and other measures also helped keep cases down.

- Port Orford-Langlois School District 2CJ in Oregon: In two tiny towns on the coast of Oregon, this district built up community trust and used a cautious, step-by-step reopening strategy to make it through the 2020-2021 school year with zero cases identified in school buildings.

- P.S. 705 in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, New York: This elementary school brought 55% of students back to in-person class, well above the New York City average (40%), by utilizing comprehensive parent communication and surveillance testing of students and staff.

Here are 11 major lessons we identified from the districts that kept their communities safe.

1. Collaboration with the public health department is key.

In Austin, Indiana, an existing relationship between the local school district and local public health department, built during the town’s HIV/AIDS outbreak in 2015, streamlined COVID-19 communication. The district and public health department worked together to plan school reopening, while district residents — already familiar with the health department’s HIV prevention efforts — quickly got on board with COVID-19 safety protocols.

Garrett County’s school district, in Maryland, worked with their local public health department on making tests available to students and staff. The Andrews County district, in Texas, also collaborated with the county health agency on testing and on identifying student cases in fall 2020 — though the relationship fractured later in the school year due to differing opinions on the level of safety measures required in schools.

“What the CDC basically said is that each school has to become a little health department in its own right,” said Katelyn Jetelina, epidemiologist at the University of Texas and author of the Your Local Epidemiologist newsletter; but “schools don’t have the expertise to do that,” she said. As a result, public health departments themselves may be valuable sources of scientific knowledge for school leaders.

“What’s ideal — and I’ve only seen this happen a few times — is, if there is literally someone from the health department embedded in the school district,” added Robin Cogan, legislative co-chair for the New Jersey State School Nurses Association and author of the Relentless School Nurse blog.

2. Community partnerships can fill gaps in school services.

In addition to public health departments, there are other areas where partnerships outside a school may be beneficial; partnering up to address technology and space needs was a particular theme in this project. In Oregon, the Port Orford-Langlois school district relied on the local public library to provide technology services, space for after-school homework help, wifi outside school hours, and even extracurricular activities. Meanwhile, in Garrett County, Maryland, the school district worked with churches, community centers, and other centrally-located institutions to provide both wifi and food to district families.

Both of these rural districts faced challenges with online learning, as many families did not have wifi at home. By expanding internet access through community partnerships, the districts enabled families to keep up kids’ online learning — while showing parents that school staff were capable of meeting their needs, building trust for future in-person semesters.

3. Communication with parents should be preemptive and constant.

Strong communication was one theme that resonated across all five profiles. In a tumultuous pandemic school year, parents wanted to know exactly what their schools were doing and why; the districts we profiled offered ample opportunities for parents to quickly get updates and ask questions.

For example, at Brooklyn’s P.S. 705, administrators held weekly town hall meetings — segmented by grade level — and staffed a “virtual open office,” available on a daily basis for parents to log on and ask questions. Jetelina said that such forums are an ideal opportunity for “two-way communication,” in which administrators could both talk to parents and listen to feedback.

Andrews County also held a town hall for parent questions prior to the start of the 2020 school year. In Garrett County, administrators updated a massive FAQ document (currently 22 pages) whenever a parent reached out with a question. This district, P.S. 705, and Port Orford-Langlois all gave parents the opportunity to talk to school staff in one-on-one phone calls.

Cogan pointed out that parents like to be reached on different platforms, such as text messages, Facebook, and Google classroom; by giving parents multiple options, districts may ensure that all parent questions are asked and answered.

4. Require masks, and model good masking for kids.

Mask requirements in schools have become highly controversial in fall 2021, with some parents enthusiastically supporting them while others refuse to send their children to school with any face covering. But widespread masking remains one of the best protections against COVID-19 spread, especially for children who are too young to be vaccinated.

And yes, evidence shows that young children can get used to wearing a mask all day. In the Port Orford-Langlois school district, Principal Krista Nieraeth credits responsible masking among students to their parents. Though the community leans conservative, she said, parents modeled mask-wearing for their kids, understanding the importance of masking up to prevent the coronavirus from spreading at school. Some parents even donated homemade masks to the district for students and teachers.

As Delta spreads, Cogan said, it’s important that districts require “properly fitting masks that are worn correctly” to ensure that students are fully protected.

5. Regular testing can prevent cases from turning into outbreaks.

Brooklyn’s P.S. 705 leaned into the surveillance COVID-19 testing program organized by the New York City Department of Education. The city required schools to test 20% of on-site students and staff once a week, from December 2020 through the end of the spring semester; P.S. 705 tested far above this requirement during the winter months, when cases were high in Brooklyn. The testing allowed this school to identify cases among asymptomatic students, quarantine classes, and stop those isolated cases from turning into outbreaks.

School COVID-19 testing programs should test students frequently, Jetelina said. “But what’s even more important than regular testing is it’s not biased testing,” meaning the tests are required for all in-person students. Voluntary testing, she said, would be more likely to include only the families who are also more likely to follow other safety protocols.

More districts are now working to set up regular testing programs for fall 2021, using funding from the American Rescue Plan, Cogan said. If regular testing isn’t possible, it’s still crucial for a district to make tests easily available — with timely results, in under 24 hours — to a student’s close contacts when a case is identified at school. Both the Garrett County and Andrews County school districts worked with their local public health departments to make such testing possible.

6. Improve ventilation and hold classes outside where possible.

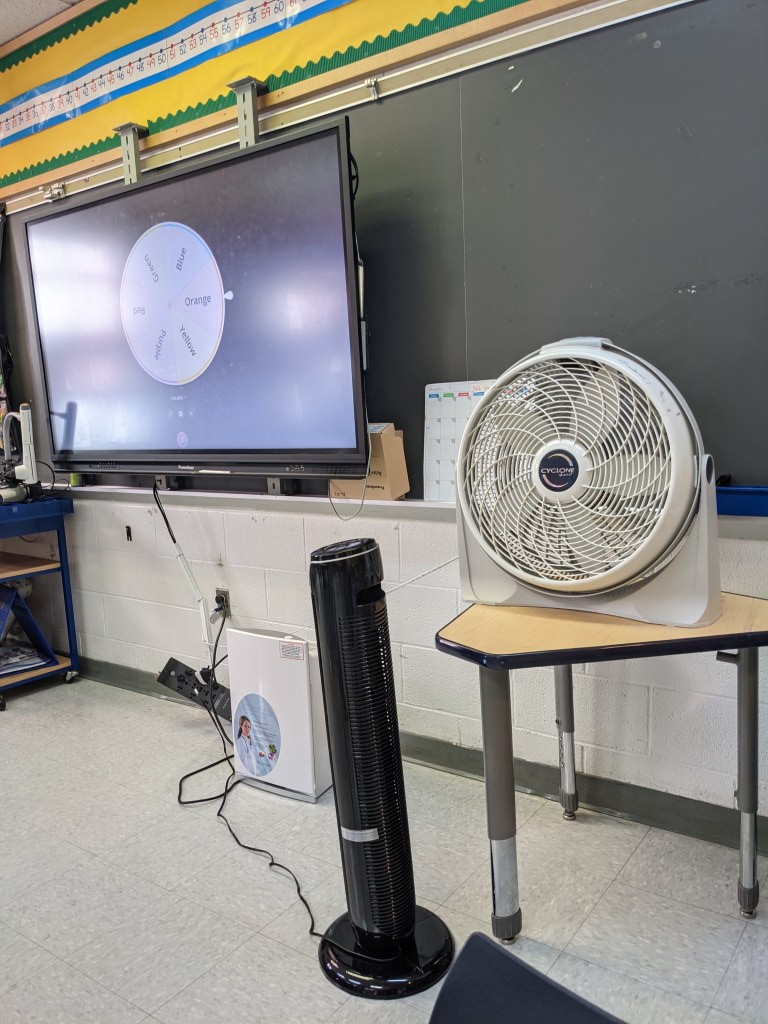

In addition to funding for COVID-19 testing, the American Rescue Plan made billions of dollars available for improvements to school ventilation systems. The Garrett County and Austin, Indiana school districts both took advantage of this funding to upgrade HVAC systems in their buildings and buy portable air filtration units.

In Andrews County — where the West Texas weather stays warm through much of the year — the school district opted for more natural ventilation: opening doors and windows, and holding class outside whenever possible. The extra time outdoors was also beneficial to the mental health of students who had been cooped up indoors in spring 2020, administrators said.

Still, outdoor class may not be possible for districts in urban areas, Cogan said. In these schools, windows and doors may be locked down to protect against a different public health crisis: the threat of gun violence.

7. Schools may still be focusing too much on cleaning.

In July 2020, Derek Thompson, staff writer at The Atlantic, coined the term “hygiene theater”: many businesses and public institutions were devoting time and resources to deep-cleaning — even though numerous scientific studies had demonstrated that the virus primarily spreads through the air, not through surface contact.

More than a year later, hygiene theater is alive and well in many school districts, COVID-19 Data Dispatch interviews with school administrators revealed. When we asked in interviews, “What were your safety protocols?”, administrators often jumped to deep-cleaning and bulk hand sanitizers. Ventilation would come up later, after additional questioning. At the Andrews County district, for example, custodians would clean a classroom once a case was identified — but close contacts of the infected student were not required to quarantine.

“Cleaning high-touch areas is very important in schools,” Cogan said. But mask-wearing, physical distancing, vaccinations, and other measures are “higher protective factors.”

8. Give agency to parents and teachers in protecting their kids.

Last school year, many districts used temperature checks and symptom screenings as an attempt to catch infected students before they gave the coronavirus to others. But in Austin, Indiana, such formalized screenings proved less useful than teachers’ and parents’ intuition. Instructors could identify when a student wasn’t feeling well and ask them to go see the nurse, even if that student passed a temperature check.

Jetelina said that teachers and parents can both act as a layer of protection, stopping a sick child from entering the classroom. “Parents are pretty good at understanding the symptoms of their kids and the health of their kids,” she said.

In Andrews, Texas, district administrators provided parents with information on COVID-19 symptoms and entrusted those parents to determine when a child may need to stay home from school. The Texas district may have “gone way overboard with giving parents agency,” though, Cogan said, in allowing students to opt out of quarantines and mask-wearing — echoing concerns from the Andrews County public health department.

9. We need more granular data to drive school policies.

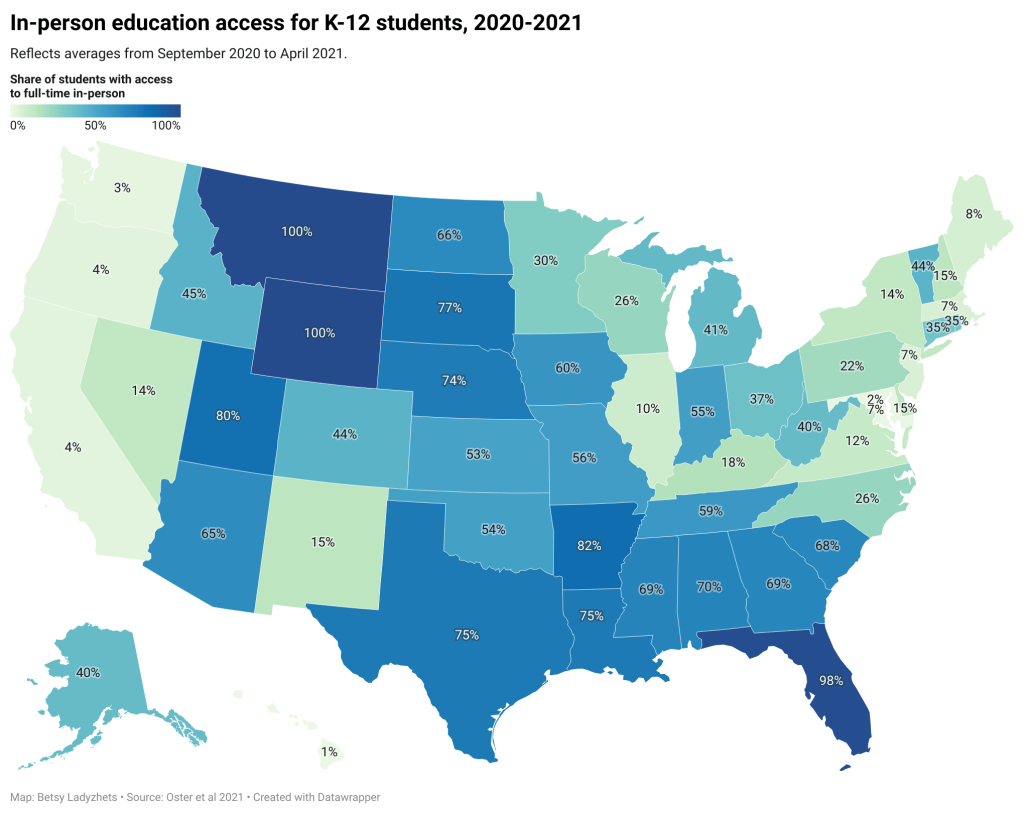

The COVID-19 Data Dispatch has consistently called out a lack of detailed public data on COVID-19 cases in schools. The federal government still does not provide such data, and most states offer scattered numbers that don’t provide crucial context for cases (such as in-person enrollment or testing figures). Without these numbers, it is difficult to compare school districts and identify success stories.

The “Opening” project also illuminated another data issue: Most states are not providing any COVID-19 metrics down to the individual district, making it hard for school leaders to know when they must tighten down on or loosen safety protocols. At the tiny Port Orford-Langlois district in Oregon, for example, administrators had to rely on COVID-19 numbers for their overall county. Even though the district had zero cases in fall 2020, it wasn’t able to bring older students back in person until the spring because outbreaks in another part of the county drove up case numbers. Cogan has observed similar issues in New Jersey.

At a local level, school districts may work with their local public health departments to get the data they need for more informed decision-making, Jetelina said. But at a larger, systemic level, getting granular COVID-19 data is more difficult — a job for the federal government.

10. Invest in school staff and invite their contributions to safety strategies.

School staff who spoke to the COVID-19 Data Dispatch for this project described working long hours, familiarizing themselves with the science of COVID-19, and exercising immense determination and creativity to provide their students with a decent school experience. Teaching is typically a challenging job, but in the last eighteen months, it has become heroic — even though many people outside school environments take this work for granted, Jetelina said.

Districts can thank their staff by giving them a say in school safety decisions, Cogan recommended. “Educators, they’ve had a God-awful time and had a lot more put on them,” she said. But “every single person that works in a school has as well.” That includes custodians, cafeteria workers, and — crucially — school nurses, who Cogan calls the “chief wellness officer” of the school.

11. Allow students and staff the space to process pandemic hardship.

About 117,000 children in the U.S. have lost one or both parents during the pandemic, according to research from Imperial College London. Thousands more have lost other relatives, mentors, and friends — while millions of children have faced job loss in their families, food and housing insecurity, and other hardships. Even if a school district has all the right safety logistics, school staff cannot truly support students unless they allow time and space to process the trauma that they’ve faced.

P.S. 705 in Brooklyn may serve as a model for this practice. School staff preemptively reached out to families when a student missed class, offering support. “705 is just the kind-of place where it is a ‘wrap your arms around the whole family’ kind-of a school,” one parent said.

On the first day of school in September 2021 — when many students returned in-person for the first time since spring 2020 — the school held a moment of silence for loved ones that the school community has lost.

These lessons are drawn from school communities that were successful in the 2020-2021 school year, before the Delta variant hit the U.S. This highly-transmissible strain of the virus poses new challenges for the fall 2021 semester. The data analysis underlying this project primarily led us to profile rural communities, which may have gotten lucky with low COVID-19 case numbers in previous phases of the pandemic — but are now unable to escape Delta. For example, the Oregon county including Port Orford and Langlois saw its highest case rates yet in August 2021.

The Delta challenge is multiplied by increasing polarization over masks, vaccines, and other safety measures. Still, Jetelina pointed out that there are also “a ton of champions out there,” referring to parents, teachers, public health experts, and others who continue to learn from past school reopening experiences — and advocate for their communities to do a better job.

Have you taken lessons from the “Opening” project to your local school district? Do you see parallels between the five communities in this project and your own? If so, we would love to hear from you. Comment below or email betsy@coviddatadispatch.com.

The COVID-19 Data Dispatch’s “Opening” series is available for other publications to republish, free of charge.

More from the Opening series