Two years into the pandemic, you might think that, by now, schools would have figured out a strategy to continue teaching kids while keeping them safe from the coronavirus. Instead, the school situation is more chaotic than ever—thanks to Omicron combined with staff shortages, pandemic fatigue, and other ongoing issues.

Thousands of schools went online or closed entirely this week, likely more than in any other week since spring 2020. And yet: there is currently no national data source tracking COVID-19 cases in schools, and nine states fail to report any data on this crucial topic.

This week, I had a story published in education outlet The Hechinger Report about the challenges that schools faced in staying open during the fall 2021 semester. For the story, I returned to the five school communities that I profiled last summer during my Opening project to see how they fared in the fall.

The story identifies four major challenges:

- Quarantines: When a school or district faces a COVID-19 outbreak, contact tracing for all of the cases can quickly become incredibly time-consuming. This work “can be very burdensome for the school and the health department,” pediatrician Leah Rowland told me—especially when a school doesn’t have its own school nurse.

- Testing: Surveillance testing can help identify cases early, while test-to-stay programs can keep kids out of quarantine; in fact, the CDC recently endorsed test-to-stay, adding the strategy to its official schools guidance. But testing programs are costly and hard to set up; in absence of state-wide testing support, they tend to be implemented at larger and wealthier school districts.

- Staff shortages: Every single school leader and expert I spoke to for the story named staff shortages as a major challenge. “[Potential staff] can work at McDonald’s, and have a whole lot less stress and make more money than working as an instructional assistant for Garrett County Public Schools,” Alison Sweitzer, director of finance at this Maryland district, told me.

- Pandemic fatigue: In a lot of places around the U.S., schools are one of the only—if not the only—institution still enforcing COVID-19 policies, like masks and social distancing. This can drive up tension between parents and school staff; and school nurses, who act as public health experts within the school, often bear the brunt of the criticism. Robin Cogan, legislative co-chair for the New Jersey State School Nurses Association, told me that she’s never felt this exhausted, in 21 years of serving as a school nurse.

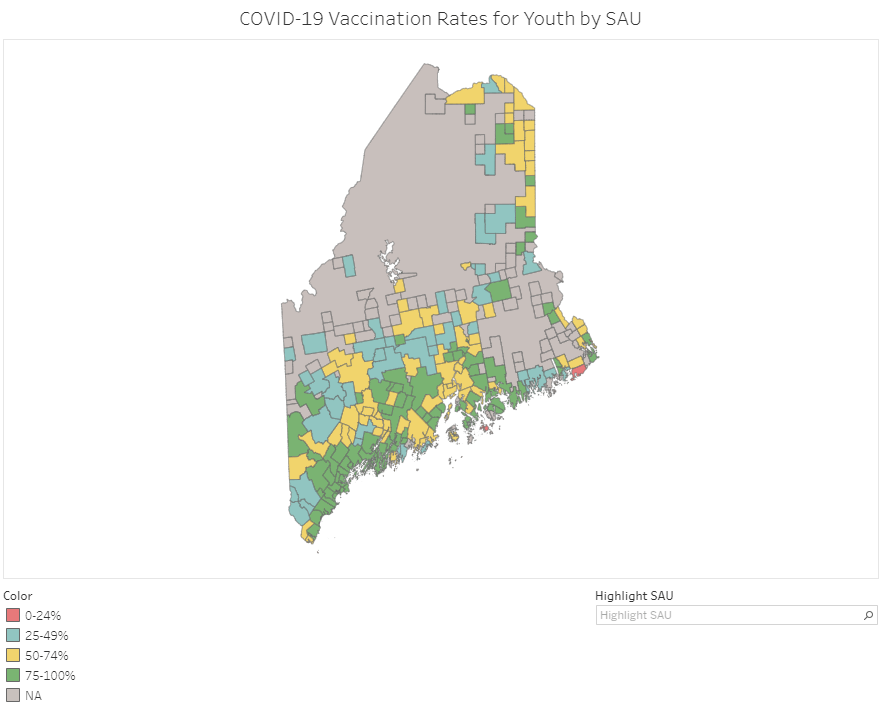

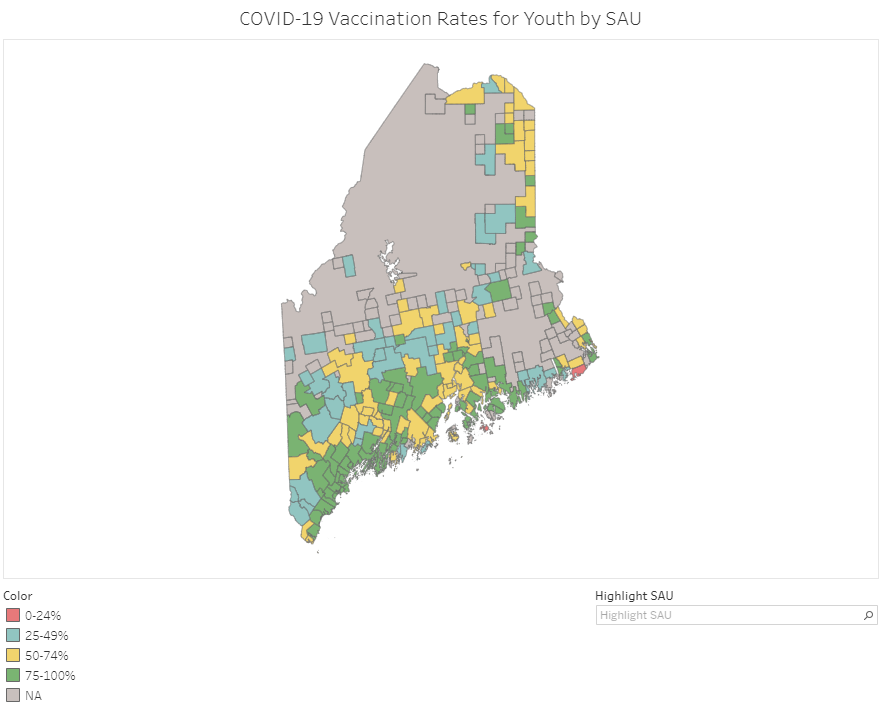

- Low vaccination rates: As of this week, about one in four children ages five to 11 has received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. This ranges wildly by state, though, with 57% of children in this age group vaccinated in Vermont compared to under 20% in much of the South. Vaccinated students and staff don’t have to quarantine when they’re exposed to a COVID-19 case, but despite this strong motivator, the school leaders I spoke to have not seen much enthusiasm for the shots.

I reported most of that Hechinger Report story before Omicron hit the U.S. But it’s clear to see how the new variant has exacerbated all of these challenges. As this super-contagious variant hits schools, cases are increasingly rapidly—leading to more quarantines and contact tracing pressures. School staff are getting sick, intensifying shortages. And the students and staff who are unvaccinated are the most vulnerable.

“Pediatric hospitalizations are at the highest rate compared to any prior point in the pandemic,” CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky said at a press briefing on Friday. The CDC is investigating whether this increase reflects an inherent severity of Omicron in children or whether it’s simply the product of record-high cases everywhere. Either way, though, the data clearly show that vaccination is the best way to protect children from severe COVID-19. For children under age five, Dr. Walensky said, “it’s critically important that we surround them with people who are vaccinated to provide them protection.”

According to Burbio’s K-12 School Opening Tracker, 5,441 schools had disruptions in the week of January 2. Those disruptions include schools going online or canceling instruction entirely—anything caused by the pandemic, as opposed to by weather or some other reason. This is higher than any other week in the 2021-2022 school year by a long shot; the previous record was 2,846 disruptions in early November.

New York City has been one of the U.S.’s first Omicron hotspots, and the variant has had a massive impact on the city school system. Case rates shot up in December, with almost 5,000 new cases reported by the city Department of Education (DOE) in the week ending December 26. This number, as well as January DOE data, is likely a massive undercount, though, because of the sheer number of cases being reported within the city right now.

The PRESS NYC schools dashboard, which references DOE data, provides this caveat: “As we understand it, the Situation Room cannot keep up with cases coming in and many cases aren’t even making it into DOE data.”

Stories from inside the public school system suggest that kids are going into classrooms just to sit in study hall and, very likely, infect each other. One Reddit post from a NYC high school student described the case numbers at their school shooting up from six total cases in mid-December, to 100 on January 3, to over 200 by the end of this week. The majority of those cases weren’t yet reflected in DOE data, the student said.

Yet NYC’s new mayor, Eric Adams, seems determined to keep schools open at all costs.

Other districts have also had their fair share of conflict this week. In Chicago, teachers are on strike for safer in-person conditions. The situation has led to classes getting canceled entirely, as the school district locked striking teachers out of their online accounts—preventing them from teaching remotely. And in many other districts, including Seattle and Washington D.C., the start of the spring semester was delayed as the district sought to test all students, teachers, and staff before reopening.

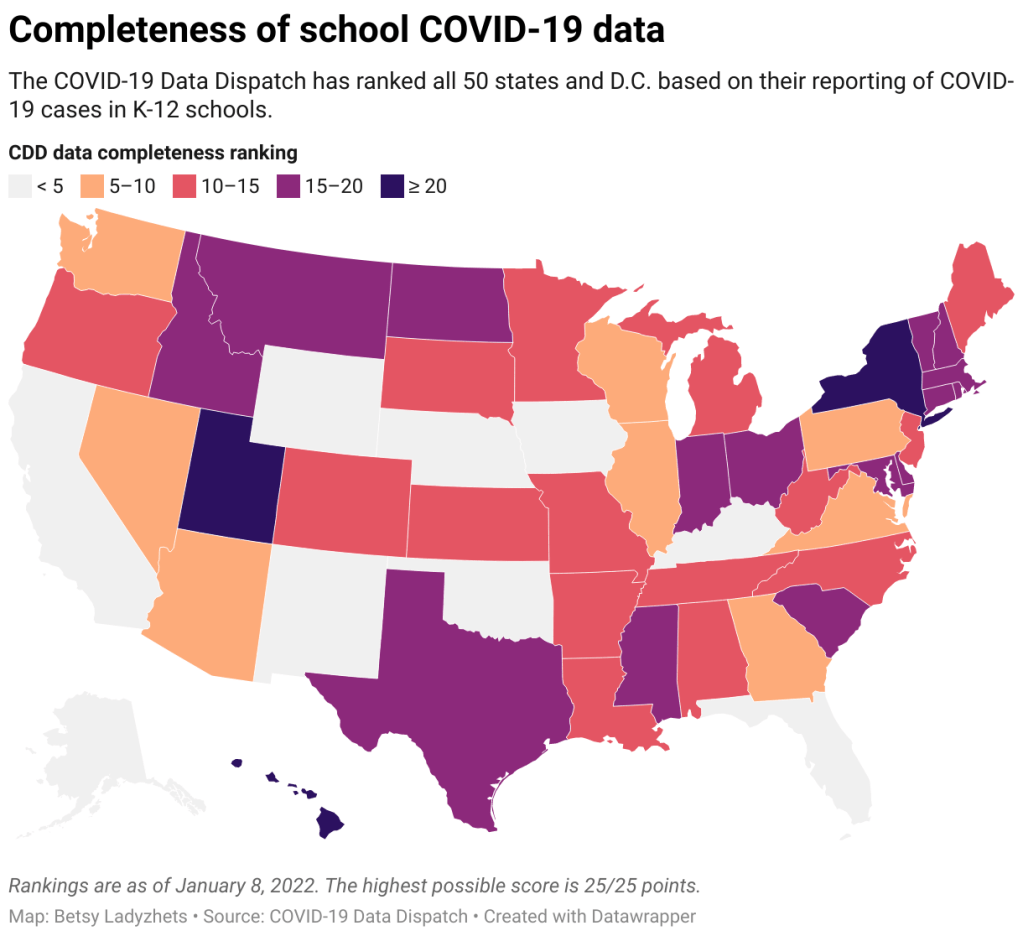

With all of this tension in mind, I set out yesterday to update my K-12 school data annotations for the first time in several months. These annotations reflect the availability of data on COVID-19 cases and related metrics in school buildings, by state and at the national level.

Here’s what I found:

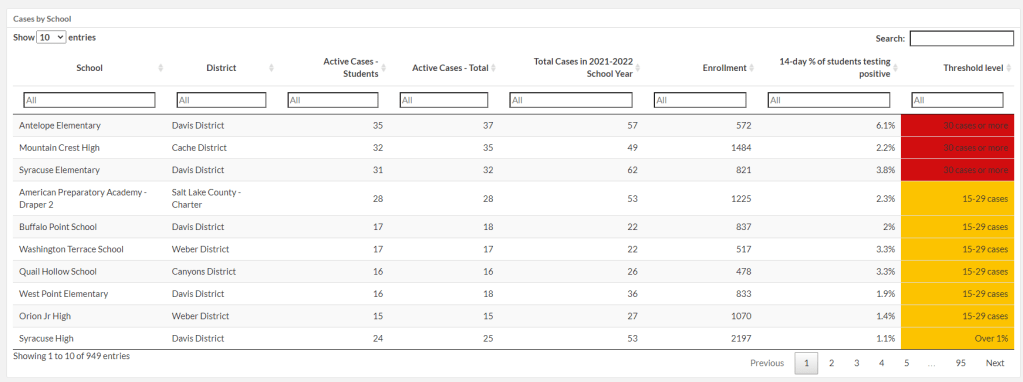

- 31 states and D.C. are reporting data on COVID-19 cases in K-12 school settings. There’s a lot of variability in this reporting, though, from states like Connecticut, which reports a detailed breakdown of cases by school (including downloadable historical data), to states like Maine, which only reports cases in “active outbreaks.”

- 10 states are reporting what I categorize as “somewhat” cases in K-12 schools. This includes states like Arizona, which reports the number of schools with COVID-19 outbreaks by county (but no case numbers), and Illinois, which reports cases in school-aged children (but not cases that are school-specific).

- Nine states are not reporting any K-12 school data. These states are: Alaska, California, Florida, Iowa, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming. Note, both Florida and Kentucky used to report school data, but have discontinued this reporting since last school year.

- New York continues to have the most complete school data, by my assessment, as it’s the only state to report both COVID-19 tests and school enrollment.

- Six states are now reporting in-person school enrollment, a key metric needed to analyze COVID-19 data: Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, New York, Texas, and Utah.

!function(){“use strict”;window.addEventListener(“message”,(function(e){if(void 0!==e.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var t=document.querySelectorAll(“iframe”);for(var a in e.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var r=0;r<t.length;r++){if(t[r].contentWindow===e.source)t[r].style.height=e.data["datawrapper-height"][a]+"px"}}}))}();

In short, while a lot of data on COVID-19 in schools are available from state public health departments, these data are wildly unstandardized and difficult to analyze holistically. See the annotations page for more details on your state.

Meanwhile: at this time, there is no national data source on COVID-19 cases in schools. The federal government has never reported these data; the best that our federal health agencies can do, apparently, is compile rarely-updated dashboards of school learning modes (i.e. which districts are in-person vs. remote). Last school year, a couple of research projects sprung up to compile information from state agencies and other sources; but as of now, those projects are all discontinued.

While a number of studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of common safety policies (masks, vaccinations, ventilation, etc.), many of the researchers who study school COVID-19 safety have to use small sample sizes, such as a single district or state. CDC researchers often rely on proxies like county case rates to analyze the impact of different policies. This research is a far cry from the work that we could do with a comprehensive, national dataset of COVID-19 cases in schools.

Without detailed data on COVID-19 in schools, it’s difficult to make good policy decisions. The data void leaves space for pundits on both sides of the aisle: some can argue that schools are safe and must remain open in-person no matter how high community cases get, while others can argue that schools are incredibly dangerous and must close.

The COVID-19 in schools data void is wider than ever right now, even though we need information desperately as Omicron spreads.

More K-12 reporting