This week, I had a story on COVID-19 testing published in Slate’s Future Tense vertical. The piece explores how testing will change in the next few months as more Americans become vaccinated and rapid tests become more widely available, with a practical focus: how should you interpret the test numbers on your local COVID-19 dashboard?

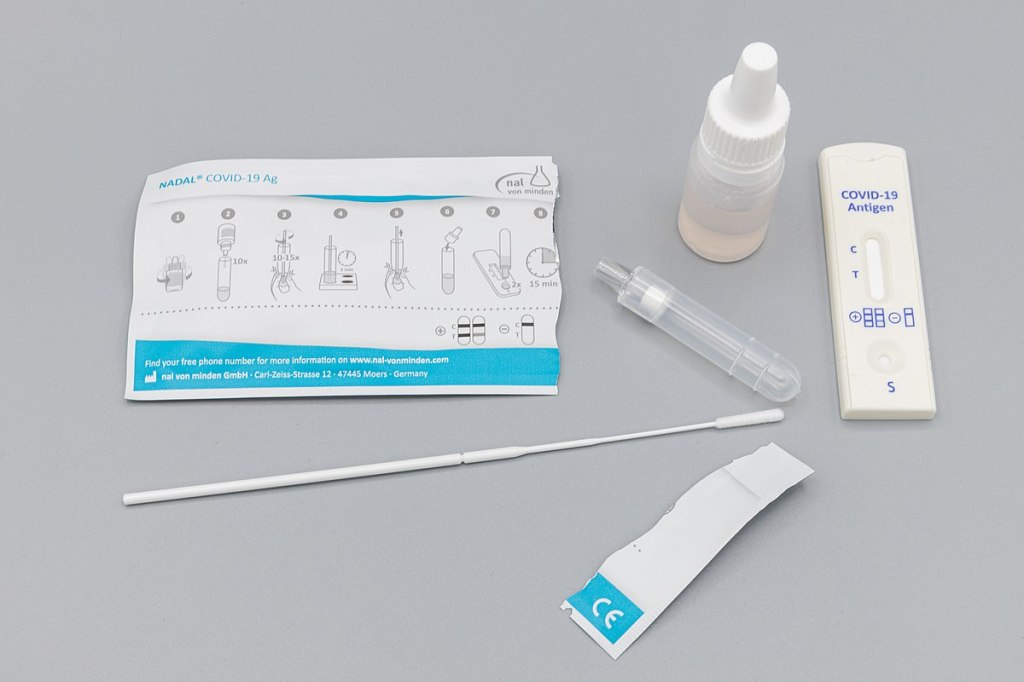

Overall, I found, we will need to keep getting tested even post-vaccination. But the purpose of testing may shift, for many of us in the U.S., from diagnostic testing—a test to figure out if you are currently sick with COVID-19—to more screening and surveillance testing—tests to identify case trends and stomp out outbreaks in a broader community. This shift may be aided by the rise of rapid, at-home tests, which are becoming much more widely available thanks to investment from the federal government. Just this week, USA Today reported that at-home tests will soon be sold at national pharmacies CVS, Walgreens, and Walmart.

In the CDD today, I’m excited to share one of the interviews I conducted for the piece, with Dan Larremore, a statistician at the University of Colorado and long-time advocate for the potential of rapid tests. We talked on April 2, just days after two major developments in the testing space: the FDA gave Emergency Use Authorization to several rapid tests for over-the-counter use, and the CDC and NIH announced a massive study to investigate how well these tests work for population-level screening. (One more piece of context: when we talked, case numbers were rising at a more concerning rate than they are now.)

Larremore and I talked about his reaction to the rapid test news, how to interpret testing numbers, other new test types that may come on the market, and more.

The interview below has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

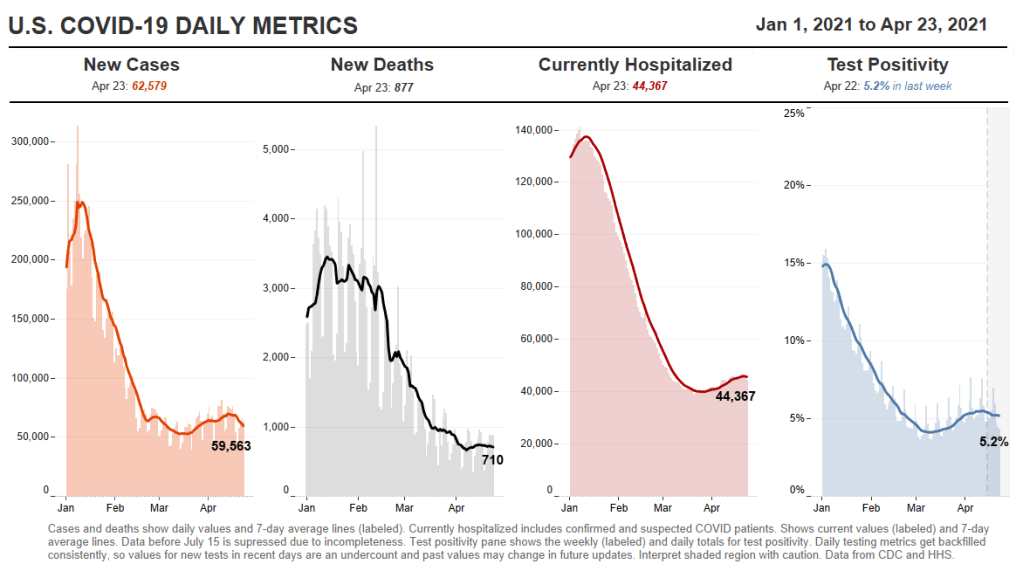

Betsy Ladyzhets: First question is, since a lot of this piece is meant to be about the numbers of testing, what would you consider the most useful metric or metrics right now to how successful testing is, whether that’s test positivity or other things?

Dan Larremore: I think about testing for three different reasons. One reason is information about the trajectory of the pandemic, which is things like test positivity rates, number of new cases. We test to kind-of get our bearings in the movement of the pandemic. The second reason that we test is more at the individual level, but it’s still that [same] information. And that is, I would test because I want to know, am I sick? Might I give the disease to somebody else? Or, can my current symptoms be explained by being infected? So the first two are informational.

The third reason that we might test is specifically just to break transmission chains, which is more like testing as an answer, not as a question. And so, for at-home testing, for serial testing, for the regular kind of testing that we have to do to be on campus here [at the University of Colorado]… To me, that’s much more about an intervention to slow down transmission than it is about gaining information.

So, that’s a roundabout way of answering your question. But I think, in terms of what numbers to look at, it really matters what the intention of the testing is. So if people continue to take the pandemic seriously, and continue to, like, get tested regularly, or get tested when they feel sick, then those sort of daily case numbers will remain useful and interesting. And therefore the test positivity rate information will continue to tell us something about the trajectory of the pandemic. Does that answer your question?

BL: Yeah, I think that does answer my question. Because I think that was one of the big kind of questions I had going into this story is like, is test positivity still useful if maybe, as people get vaccinated, they stopped thinking they need to get tested or as other dynamics change. But yeah, I had another person who I’ve interviewed for this story also had kind of a hierarchy description [of testing], so that definitely is a useful thing to think about.

DL: Knowing why people come in to get tested just gives you so much more interpretability of like, what the numbers mean. Here on campus, if I want to be here on campus, I need to get tested weekly. I’ve been vaccinated, one dose, dose number two soon. But nevertheless, I still need to spit in the tube every week, and they test it. So, the test positivity rates here on campus are minuscule. Because with high compliance, everybody gets tested, so the denominator in that positivity rate is huge. At a drive up site, or at a doctor’s office, where people are coming in because they feel sick, the test positivity rates are going to be a lot higher.

And I think, as people get more and more vaccinated—regardless of the case counts—as the pandemic feels like it’s winding down, I think people may be less likely to get tested. And so you can imagine test positivity rate being driven by, not just what the virus is doing, but a lot of the human behavior as well… I guess, the way that you can put it is, that you can see changes in the test positivity that are driven entirely by human behavior with respect to getting tested at all. And not so much about changes in the virus.

BL: That makes sense. And I think it’s also about access, right? Are people able to go and get tested if they feel sick? Or if you’re thinking about schools and workplaces, is their employer having everyone get tested once a week? Is that something we’re going to see more of now that we have—like, literally earlier this week, the FDA gave EUA to a bunch of antigen tests, right?

DL: Yeah, for at-home use.

BL: Right. Do you think we’re gonna finally see that massive use of rapid tests that experts have wanted to see since, like, the summer?

DL: A lot of people, myself included, have been excited about the possibility of at-home repeated antigen testing, as a way to really take community transmission levels and push them down. Because we know that asymptomatic transmission occurs, we know that getting people results rapidly is absolutely critical. Because four-day-old information is totally useless if you have infected people in those four days.

I don’t know how useful those test kits are going to be right away, like, right now, given that we just now have an EUA for that kind of at home use that we’ve been hoping for for a long time. But at the same time, cases are shooting up due to these new variants around the U.S. and more importantly, around the world. So, I think these tools are still going to be useful, especially this fall, as we get a lot more kids in school. And we start bringing people together, temperatures starting to cool off, more people are indoors. I think that having the rapid test as a screening tool will still be valuable, particularly if we see limited uptake of the vaccine.

BL: That makes sense… Another question around rapid tests is, that I know in the U.S., it’s really hard to get comprehensive data on them. I volunteered at the COVID Tracking Project, and I wrote [a blog post] about the problem of antigen test data. So I was curious as to how we will know how well the tests are working. And if there are any specific studies that you’re watching or data sources that you recommend, in terms of, like, knowing if people are actually using these at home tests.

DL: I am excited about… On the 30th, there was a press release about the NIH and CDC rolling out at-home testing to two cities.

BL: I saw that, yeah!

DL: The work that Michael Mina and I did last year was showing that, at the individual level, the trade off between test sensitivity and turnaround time, should really tell us that turnaround time is critical. Like, theoretically, at the individual person level, the rapid test idea is really, really good. What we’ve not yet seen—outside of Slovakia—is the ability to flood the zone with tests, as Fauci put it, and just catch as many positives as possible and drive the epi curve downward, just because of the rapid tests.

My feeling is that, really, the proof is in the pudding. If people can, at a community level, use a boatload of rapid tests regularly for a few weeks, and we can watch the new cases spike as we find those positives and then crash as we break all the transmission chains. That’s the key thing. That’s the key thing that I’m looking out for in these new trials.

The Slovakia folks showed some of the limitations of this [strategy]. There’s a paper in Science where they wrote up their results. And basically what they found was the rapid testing worked really well, but the problem was on the isolation side. [Not everyone who tests positive can truly and effectively isolate.] In the short term, while they still had the supplies, these three waves of everybody in the country getting tested, worked like they were supposed to work, worked like the theory said. However, once you stop testing, you take your foot off the brakes, things re-accelerate. The second thing is that a lot of folks in particularly rural areas were like, okay, well, I’m positive, but I live with my family. How am I going to isolate? So unlike on a college campus here, where when somebody tests positive, we have a separate dorm set up for them for two weeks—in real life, that isolation stuff is going to be harder.

BL: So it’s kind-of like, you need to pair it with the social services aspect, or some other way to help people out. I know, in New York, there’s a hotel room program, where if you test positive, you can contact the City Department of Health, and they’ll like, put you up in a hotel for two weeks. I don’t know how much it gets used, but it definitely seems like something that should be around in more places.

DL: I mean, even if it’s just supporting people, by telling them like, this is gonna be awkward, but wear your mask at home, and don’t hang out with your family. Go watch TV in the basement, or, you know, otherwise keep distance from people. Whatever these interventions are, they can help. And we know that what we call the secondary attack rate is actually not that high. So, even among people who live in the same household, even among spouses, if one person is sick, that doesn’t mean that the other person definitely gets it. It’s only [around 20%] chance that they do. We looked at pairs of roommates here on campus, and studied [transmission between] them. And even among roommates, the secondary attack rate is not that high [20-28%].

BL: Well, that brings me to another question I wanted to ask you, which is how public health communication around testing either is changing or should be changing in order to express like, okay, maybe you’ve been vaccinated, but you still need to get tested, or what needs to be communicated about these at home tests, or any other messages that you think are important to be conveying.

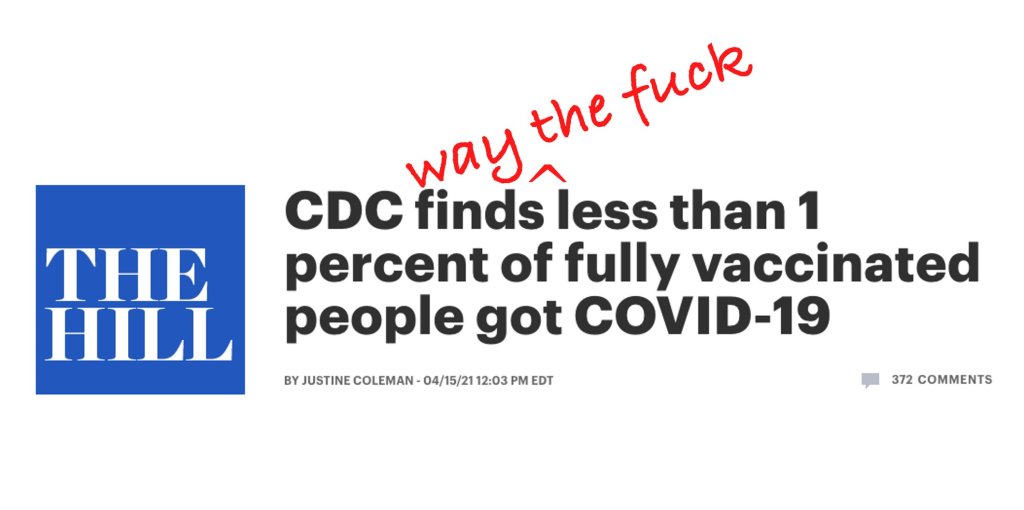

DL: One thing that’s important is that we know that we need to keep our eye on the variants. And evidence is emerging… that there are some breakthrough variants, they are less well handled by the vaccine, even though the vaccine works really well… So, testing is going to remain important, even as, more broadly, the vaccine protects people from the most severe disease.

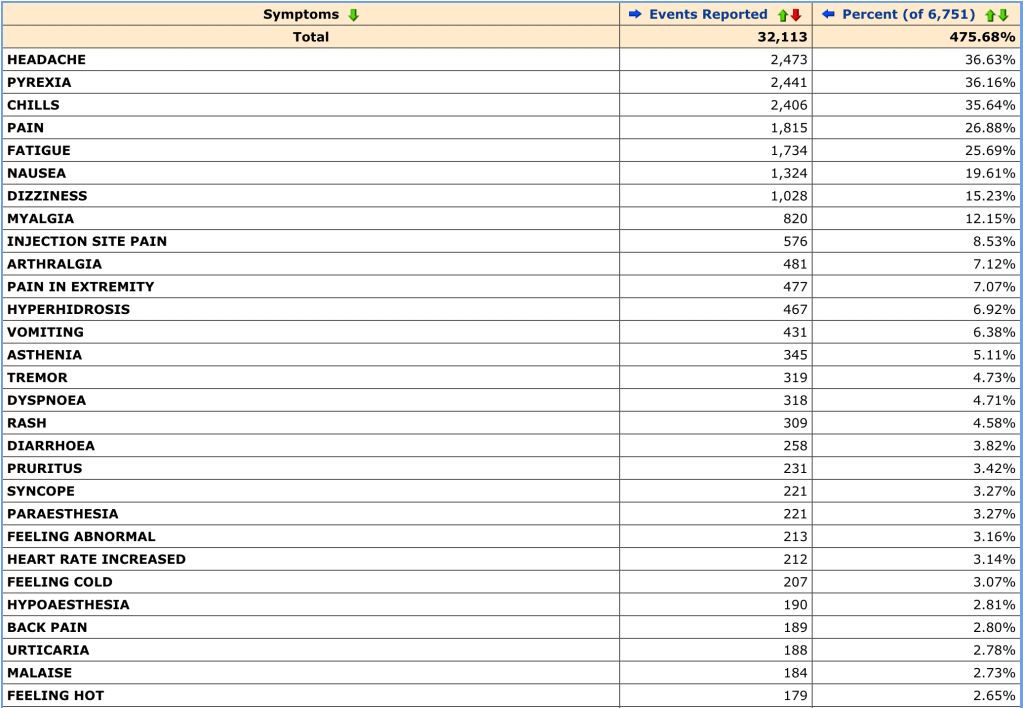

We’re seeing a really interesting split right now, right? Where like, cases are going up, and we expect hospitalizations to then go up, and then mortality to go up. But I wonder if we’re gonna see that in the U.S. this time. Like, week on week, mortality continues to go down. And the question is, are we gonna get it again?

BL: Is it gonna go up again?

DL: Or did we vaccinate enough of the high-risk people that the mortality stays flat even while cases go up?

BL: I definitely think there’s going to be kind-of a demographic aspect of it. Like,I’ve seen charts where people do, with the HHS hospitalization data, they publish it by age. So, you can see that hospitalizations are going way up in people ages, like, 18 to 30, but not so much in seniors. Although, kind-of tangentially, one data gap that I get annoyed by is that there’s very little demographic data for testing. Like, if you look at race data, for example, there are maybe five states that publish testing data by race and ethnicity. And there’s not a lot of it by age. So it’s kind-of hard to track patterns there.

DL: I mean, I don’t know what the right messaging is around testing, other than, [if you feel like you’re sick], if you have the symptoms, you’ve got to go get tested. It doesn’t matter if you’re vaccinated or not. If you feel sick, you should go get tested. If you are going to be around somebody who you know is really vulnerable, if testing is available, go get tested.

I still think it’s a valuable intervention, especially in places where vaccine uptake is low or vaccine availability is low. But I think the question is, like, really, how long is—what’s the expiration date on recommendations about testing? If 70% of the US is vaccinated by July, let’s say, does it still make sense to recommend a huge amount of testing? And I don’t know the answer to that. What I would like to see is people equipped for this fall, if there are spikes in cases, or if there are variants that are circulating even among vaccinated people, it would be amazing if, like, a local public health authority could tell everybody, this Sunday, I want everybody to use your rapid at-home test. Report your results anonymously to this number. And, if you test positive, take it seriously, take precautions. Measures like that could preserve privacy, while still collecting that key surveillance data and crashing the epidemic curve.

BL: Right, that would be really cool to see. Are there any other types of COVID tests or surveillance methods that you think might become more useful and more prevalent in the next few months or heading into the fall?

DL: Yeah, there are two kinds. So, one key point about at-home tests is that privacy-preserving aspect. Like, I trust local public health here. But I tend to vote left of center and generally trust the government. I live in Colorado, and not everybody feels that way. There’s definitely a strong libertarian independent streak. And I feel like one of the key advantages of at-home tests is that they appeal to that kind of person. They empower a person and their family to make health decisions, and they give you the information. But they don’t necessarily get recorded by something like COVID Tracking Project or HHS.

BL: Yeah.

DL: There’s less visibility for authorities, but for some folks who want information that they can act on to protect themselves and others, then that’s going to be fine. And so, as much as I would like to know exactly what is happening with the pandemic, if the trade-off for lower cases is that we don’t know about a lot of cases among folks who would rather not report their data, I think that’s a fair trade-off.

BL: Yeah, that makes sense.

DL: But it’s sort of like uncomfortable for me, who likes the data to say that. You know what I mean?

BL: It reminds me of the conversation around exposure notification apps. I talked to someone who works on those apps recently, and she kind-of said the same thing, that she would rather have everyone using the app than really good data from a tiny subset of the population that’s okay with their privacy being violated.

DL: A big thing to me is that, we know that the pandemic has been political. And I don’t see any reason why we can’t have solutions that work for the person who votes left of center, the person who votes in the middle, and the person who votes right of center.

But the other kind of tests that I’m excited about, only because they’re extremely cheap and really easy, are anosmia screens. We know that loss of sense of smell is highly specific to COVID. If you don’t have a stuffy nose, and you [suddenly] can’t smell things, you probably have COVID. So, there are companies that produce, like, a little card with a scratch-and-sniff quiz. You don’t know what’s behind the panel, but you scratch, pull up a smartphone app, and then say what you think the smell is from a multiple choice test.

One of the cool things is that anosmia only occurs in around 40% of people [with COVID] if you ask them to self-report. But if you give them one of these objective quizzes, the prevalence of anosmia as a symptom goes up to [around 75 or 80%], depending on which study you look at. The important thing is that those cards cost 25 cents apiece, and multiple people can use the same card. It’s literally a scratch-and-sniff with an online quiz.

BL: That’s incredible. Do you know if there are tests like that that are up for EUA?

DL: Yeah. Roy Parker, Michael Mina, and I collaborated with a great team to write this paper last year on typical COVID testing [PCR, LAMP, and antigen testing], test sensitivity and frequency and turnaround time. Then, Roy and I teamed up with Derek Toomre at Yale School of Medicine, and took the same idea and said, well, what if we use frequent, repeated anosmia screening tests?

One of the things that I like about those is that they’re cheap. But another thing that I like about them is that nobody thinks that [a smell test is] the same thing as a proper COVID test. You can’t get them confused. [This is important because one of the questions with rapid tests is how people may interpret a negative test—they might be infected, but the virus is at a low level. So if they get a negative rapid test and then go to the gym, the test could actually have an unintended effect. But if an anosmia test tells you that you still have your sense of smell… People understand that just because you still have your sense of smell doesn’t mean that you’re COVID-free. There’s lower risk of unintended consequences.]

Anyway, I think the messaging around those [anosmia] tests is easy. They’re easy to use, you can do them at home. And they can print them for, like, a quarter apiece. So the modeling suggests that they could be pretty effective and really cheap. You could literally mail somebody a stack of 10 of these things to everybody in the U.S.

BL: And do it once a week!

DL: Yeah, do it once a week. So, that’s another kind of test that I would like to see out there. The company that Derek started, that makes those [tests], just won one of the XPRIZEs for COVID testing. So, I think that’s cool. It’s a more creative kind of test, and it’s inexpensive.

BL: Sweet. So, that was all the questions that I had. Is there anything you think is important on this topic that I should know for this article?

DL: I just think it’s really important to keep a global perspective… As with vaccines, we know there are inequities within the U.S. But there are definitely global inequities. And while we might feel like we’re on a glide path to herd immunity through vaccination here in the States, things look very different in the rest of the world. And so, the use of these tests may become more important this fall, we may get more variants globally, even as the U.S. cases go down. I think it’s an ongoing story, even if hospitalizations and deaths continue to drop here in the States.

BL: And those tests you’re talking about that are cheaper and easier to use are useful in many places, not just here.

DL: Yeah, that’s the hope… I feel generally optimistic about [the state of the pandemic], but like, hesitant.

BL: I feel you. It’s definitely weird to see everyone getting very excited about the summer when I’m kind-of sitting here in my COVID reporting bubble, like, ahhh, not there yet.

DL: Well, one of the hardest parts, I think, for public health officials is going to be, if cases are going up, but mortality and hospitalizations are flat or going down. If COVID is only making people sick, but it’s not hospitalizing and killing them. Then, like, do we just reopen everything? Do we open up the schools? That’s tough when we’ve been acclimated to keep our foot on the brakes as much as possible.