It’s the fourth year of the pandemic. I’ve written this statement in a few pitches and planning documents recently, and was struck by how it feels simultaneously unbelievable—wasn’t March 2020, like, yesterday?—and not believable enough—haven’t we been doing this pandemic thing for an eternity already?

As someone who’s been reporting on COVID-19 since the beginning, a new year is a good opportunity to parse out that feels-like-eternity. So this week, I reflected on the major trends and topics I hope to cover in 2023—both building on my work from prior years and taking it in new directions.

(Note: I actually planned to do this post last week, but then XBB.1.5 took higher priority. Hence its arrival two weeks into the new year.)

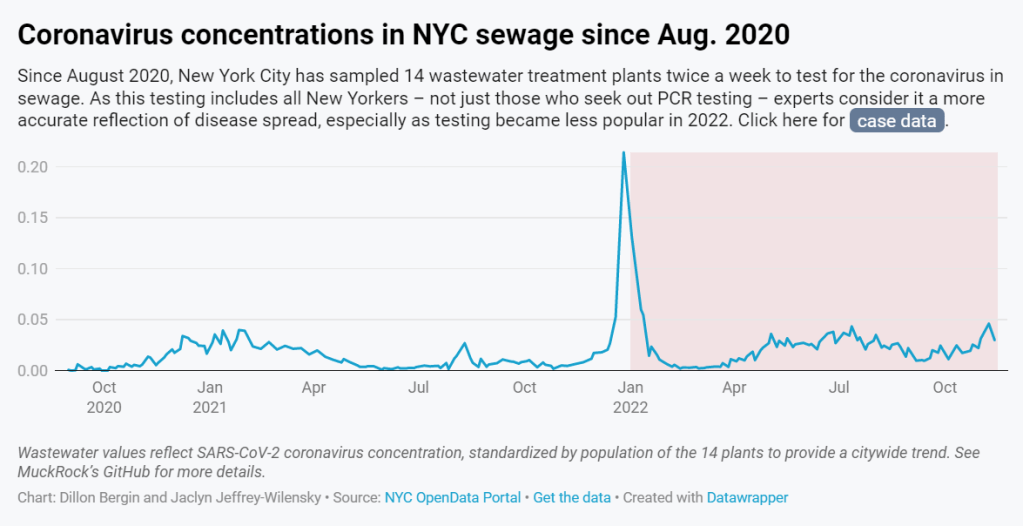

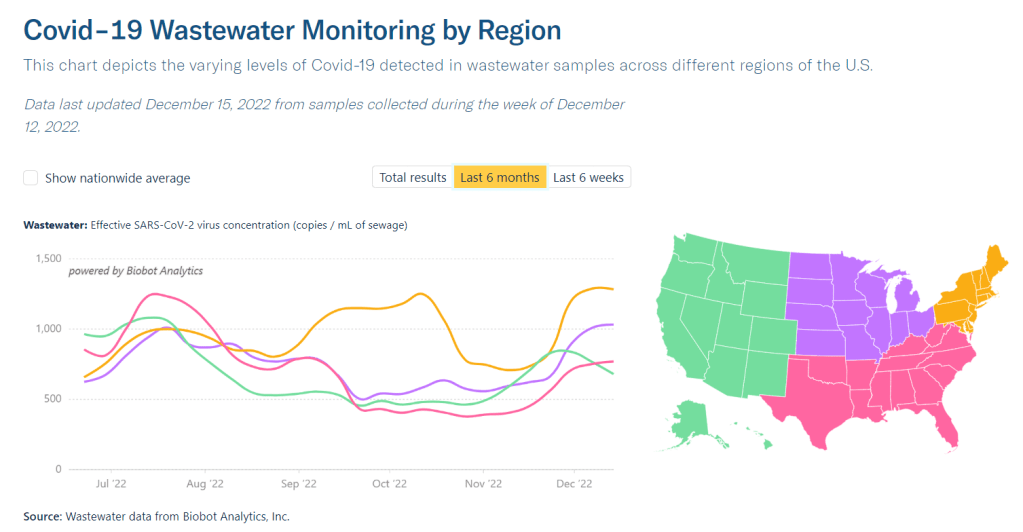

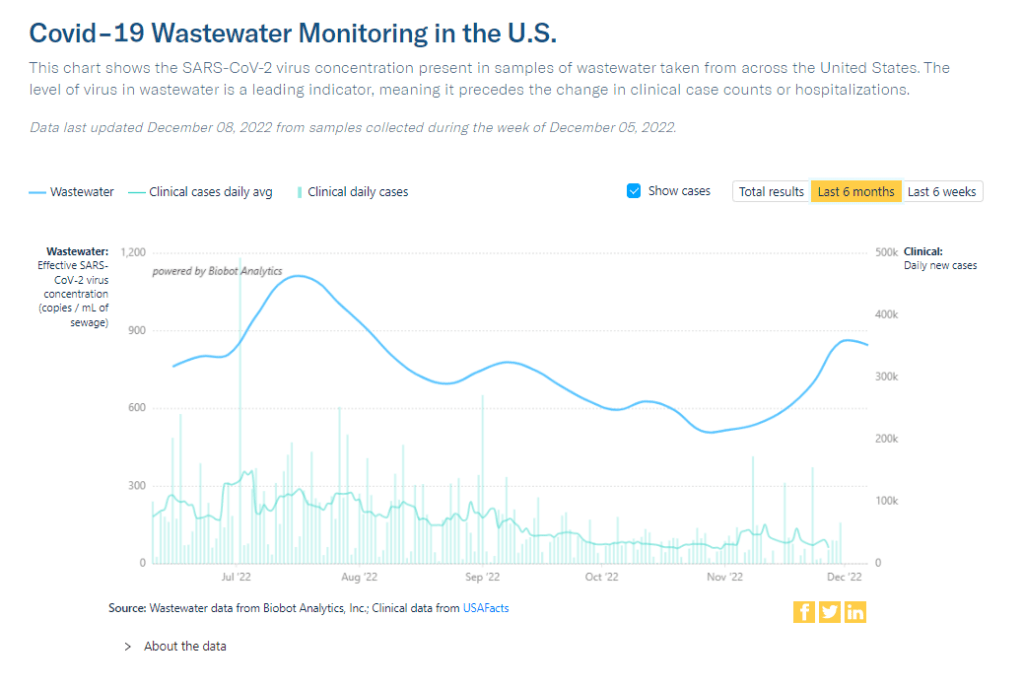

Expansions of wastewater, and other new forms of disease surveillance

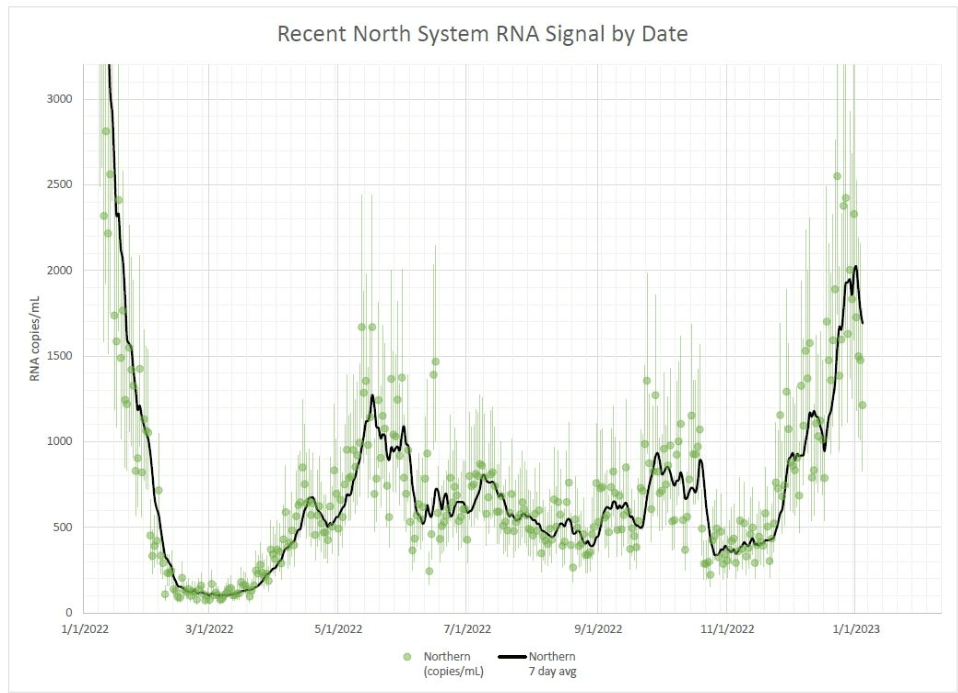

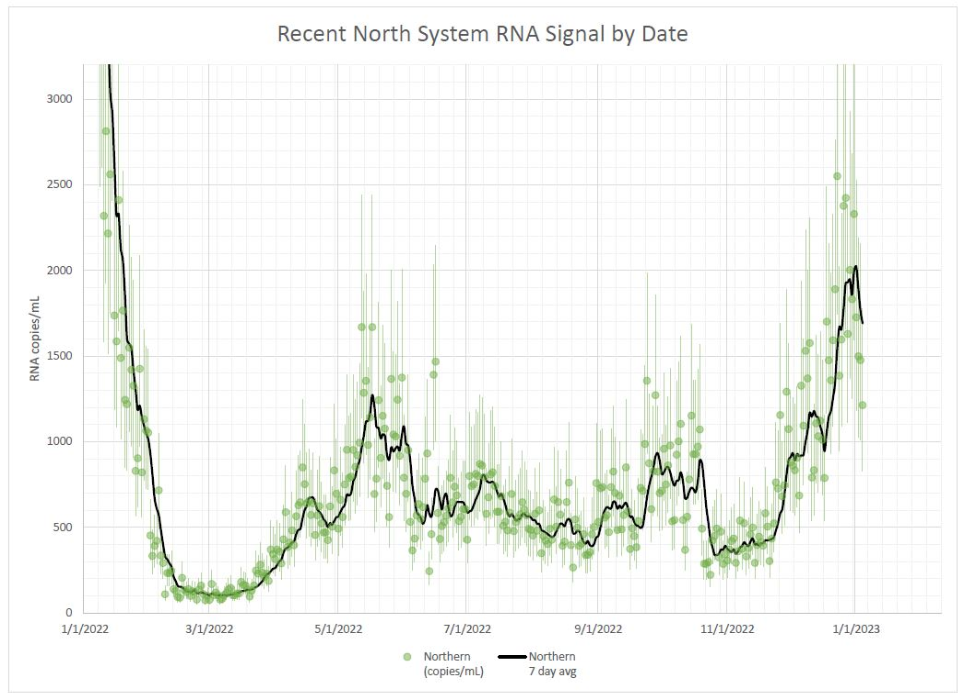

As 2022 brought on the decline of large-scale PCR testing, wastewater surveillance has proven itself as a way to more accurately track COVID-19 at the population level—even as some health departments remain wary of its utility. We also saw the technology’s use for tracking monkeypox, polio, and other conditions: the WastewaterSCAN project, for example, now reports on six different diseases.

This year, I expect that wastewater researchers and public agencies will continue expanding their use of this surveillance technology. That will likely mean more diseases as well as more specific testing locations, in addition to entire sewersheds. For example, we’re already seeing wastewater testing on airplanes. I’m also interested in following other, newer methods for tracking diseases, such as air quality monitors and wearable devices.

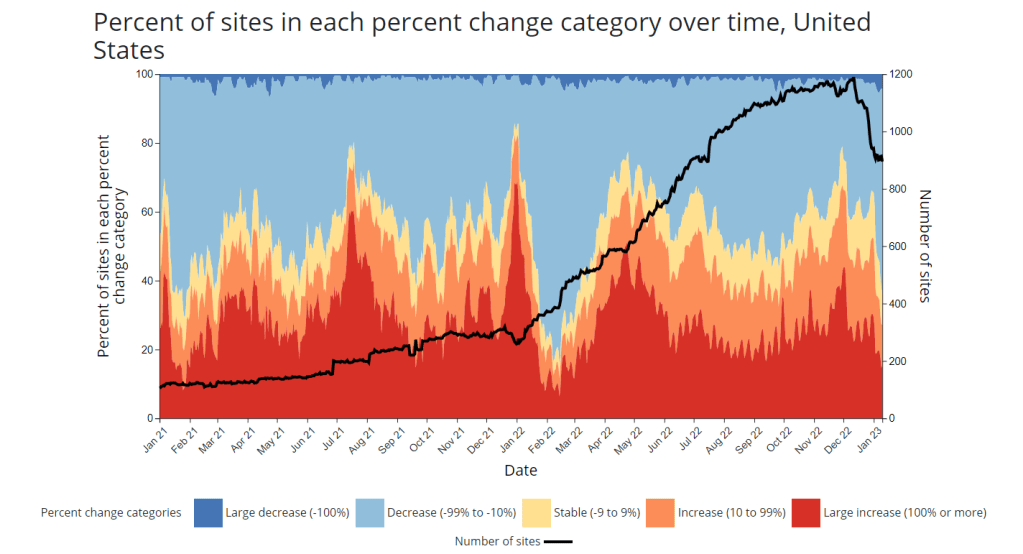

At the same time, these surveillance technologies will continue to face challenges around standardization and public buy-in. The CDC’s big contract with Biobot expires this month, and I’ve already noticed a decline in sites with recent data on the agency’s dashboard—will CDC officials and local agencies step in to fill gaps, or will wastewater testing become even more sporadic?

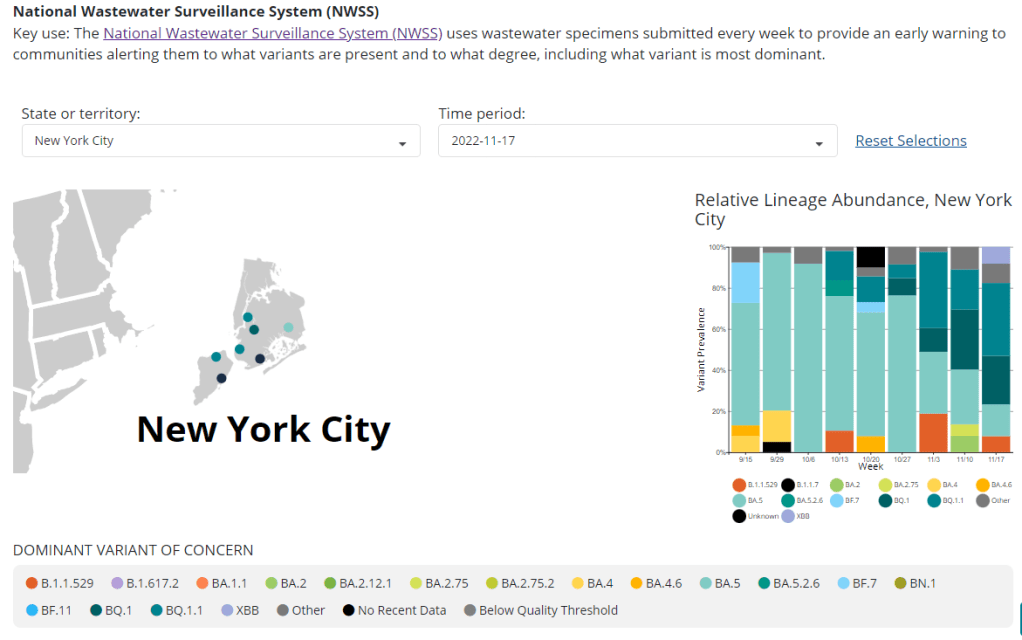

New variants, and how we track them

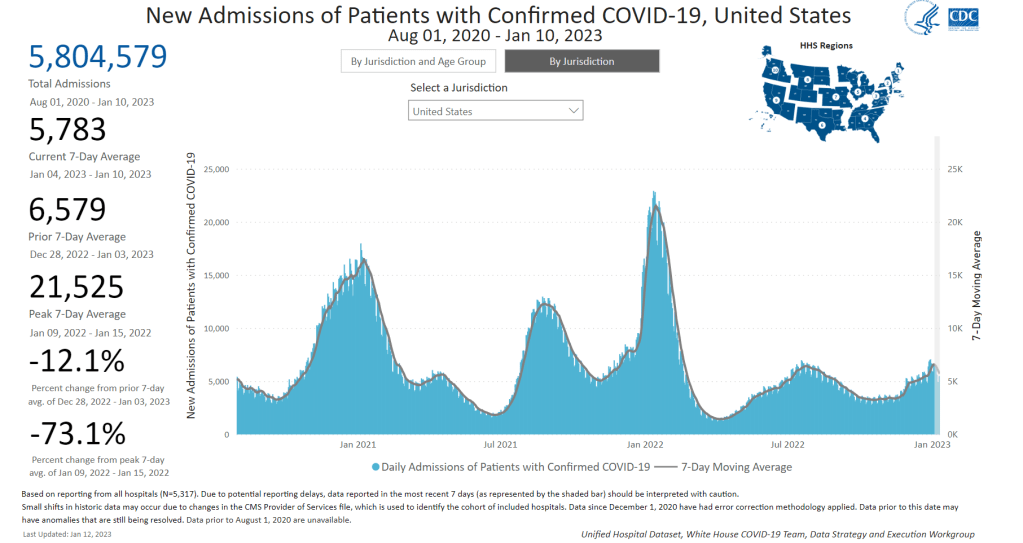

For scientists who track the coronavirus’ continued evolution, 2022 was the year of Omicron. We didn’t see all-new virus lineages sweeping the world; instead, Omicron just kept mutating, and mutating, and mutating. It seems likely that this pattern will continue in 2023, but experts need to continue watching the mutation landscape and preparing for anything truly concerning.

With declining PCR testing, public agencies and companies that track variants have fewer samples to sequence. (This led to challenges for the CDC team tracking XBB.1.5 over the holidays.) As a result, I believe 2023 will see increased creativity in how we keep an eye on these variants—whether that’s sequencing wastewater samples, taking samples directly from healthcare settings, increased focus on travel surveillance, or other methods.

Public health experts—and journalists like myself—also need to rethink how we communicate about variants. It’s no longer true that every new, somewhat-more-contagious variant warrants alarm bells: variants can take off in some countries or regions while having relatively little impact in others, thanks to differences in prior immunity, seasonality, behavior, etc. But new variants still contribute to continued reinfections, severe symptoms, Long COVID, and other impacts of COVID-19. Grid’s Jonathan Lambert recently wrote a helpful article exploring these communication challenges.

Long COVID and related chronic diseases

As regular readers likely know, Long COVID has been an increased topic of interest for me over the last two years. I’ve covered everything from disability benefits to mental health challenges, and am now leading a major project at MuckRock that will focus on government accountability for the Long COVID crisis.

Long COVID is the epidemic following the pandemic. Millions of Americans are disabled by this condition, whether they’ve been pushed out of work or are managing milder lingering symptoms. Some people are approaching their three-year anniversary of first getting sick, yet they’ve received a fraction of the government response that acute COVID-19 got. Major research projects are going in the wrong directions, while major media publications often publish articles with incorrect science.

For me, seeing poor Long COVID coverage elsewhere is great motivation to continue reporting on this topic myself, at MuckRock and other outlets. I’m also planning to spend more time reading about (and hopefully covering) other chronic diseases that are co-diagnosed with Long COVID, like ME/CFS and dysautonomia.

Ending the federal public health emergency.

Last year, we saw many state and local health agencies transition from treating COVID-19 as a health emergency to treating it as an endemic disease, like the many others that they respond to on a routine basis. This transition often accompanied changes in data reporting, such as shifts from daily to weekly COVID-19 updates.

This year, the federal government will likely do the same thing. POLITICO reported this week that the Biden administration is renewing the federal public health emergency in January, but will likely allow it to expire in the spring or summer. The Department of Health and Human Services has committed to telling state leaders about this expiration 60 days before it happens.

I previously wrote about what the end of the federal emergency could mean for COVID-19 data: changes will include less authority for the CDC, less funding for state and local health departments, and vaccines and treatments controlled by private markets rather than the federal government. I anticipate following up on this reporting when the emergency actually ends.

Transforming the U.S. public health system

Finally, I intend to follow how public health agencies learn from—or fail to learn from—the pandemic. COVID-19 exposed so many cracks in America’s public health system, from out-of-date electronic records systems to communication and trust issues. The pandemic should be a wakeup call for agencies to get their act together, before a new crisis hits.

But will that actually happen? Rachel Cohrs has a great piece in STAT this week about the challenges that systemic public health reform faces, including a lack of funding from Congress and disagreements among experts on what changes are necessary. Still, the window for change is open right now, and it may not be at this point in 2024.