The U.S. has started a new booster shot campaign, this time using vaccines designed to specifically target super-contagious subvariants Omicron BA.4 and BA.5. (For more details on the shots themselves, see last week’s post.)

Unlike previous vaccination campaigns, these boosters are available to all adults across the country who have been previously inoculated. There was no prioritization for seniors, healthcare workers, or other higher-risk adults. The official guidance from the federal government is actually pretty straightforward, for once: everyone should get the new booster. And get a flu shot soon, too, possibly even at the same time as your COVID-19 shot.

But all previously-vaccinated Americans are not facing similar levels of COVID-19 risk. Many of the same qualifications that might have warranted you an earlier dose in spring 2021 should now lead you to prioritize your Omicron booster, even if you might have been infected recently. At the same time, people who fall in these groups (or who share their households) have a good reason to continue using other safety measures after their boosters.

Here are the major qualifications for higher risk, with data to back them up:

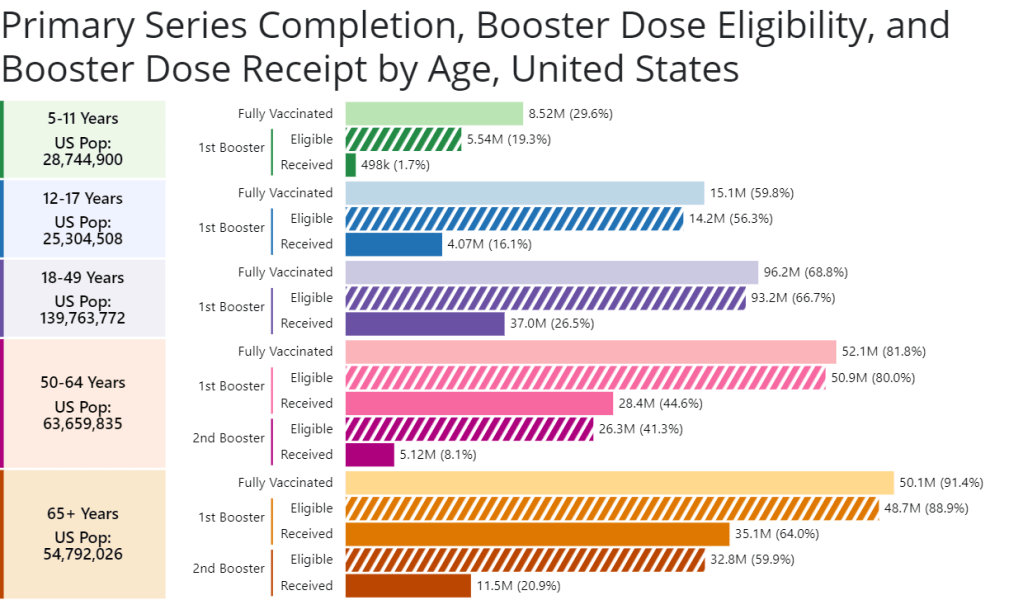

- Seniors, especially those over age 70: More than 90% of Americans over age 65 have received at least their primary vaccine series, according to the CDC, while over 70% have received at least one booster. Yet older Americans continue to have the highest rates of hospitalizations and deaths. For example, those older than 70 have consistently been hospitalized at several times the rate of younger adults (when adjusted for population). The same pattern is true for deaths among adults over age 75. Seniors who receive the new booster shots will face a lower risk of severe COVID-19 this fall and winter.

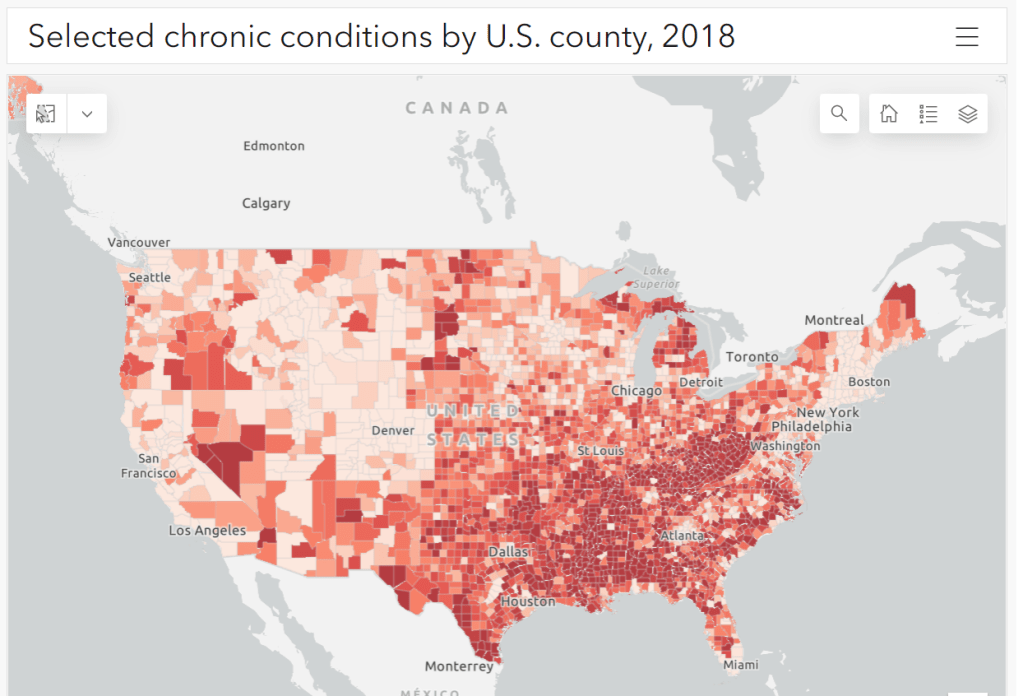

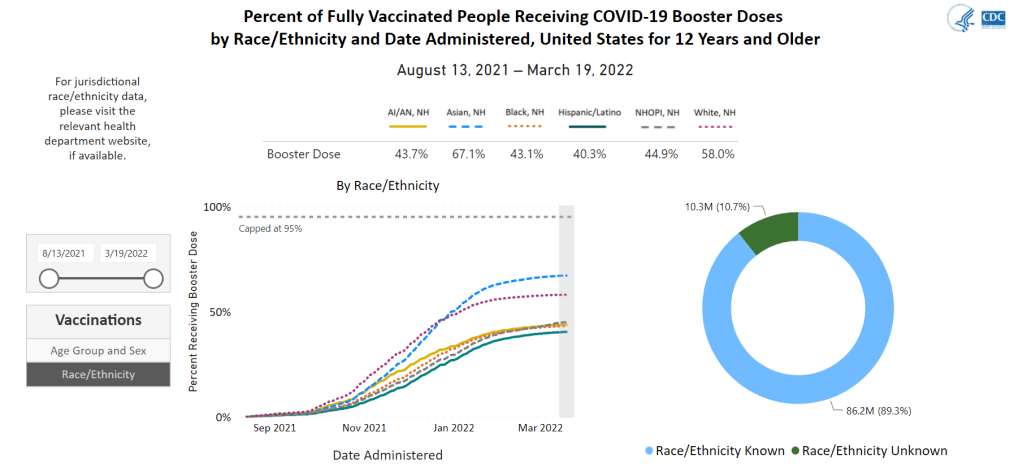

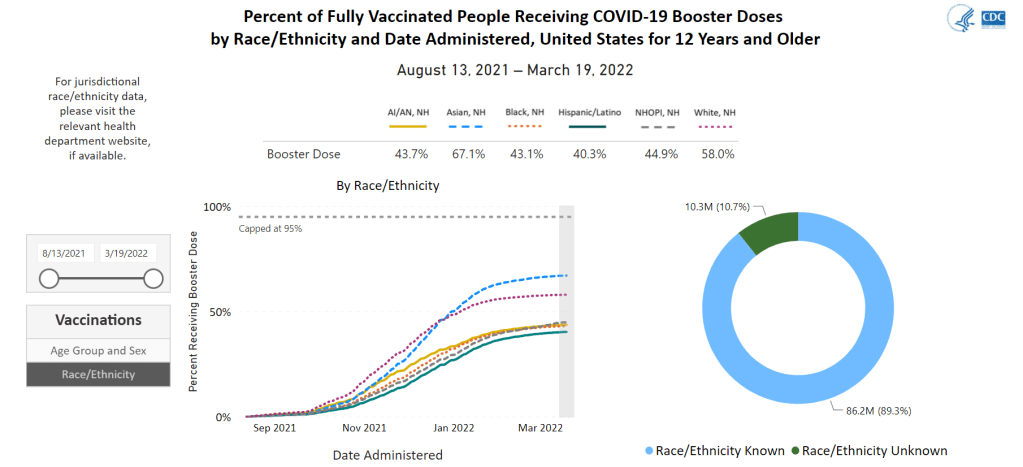

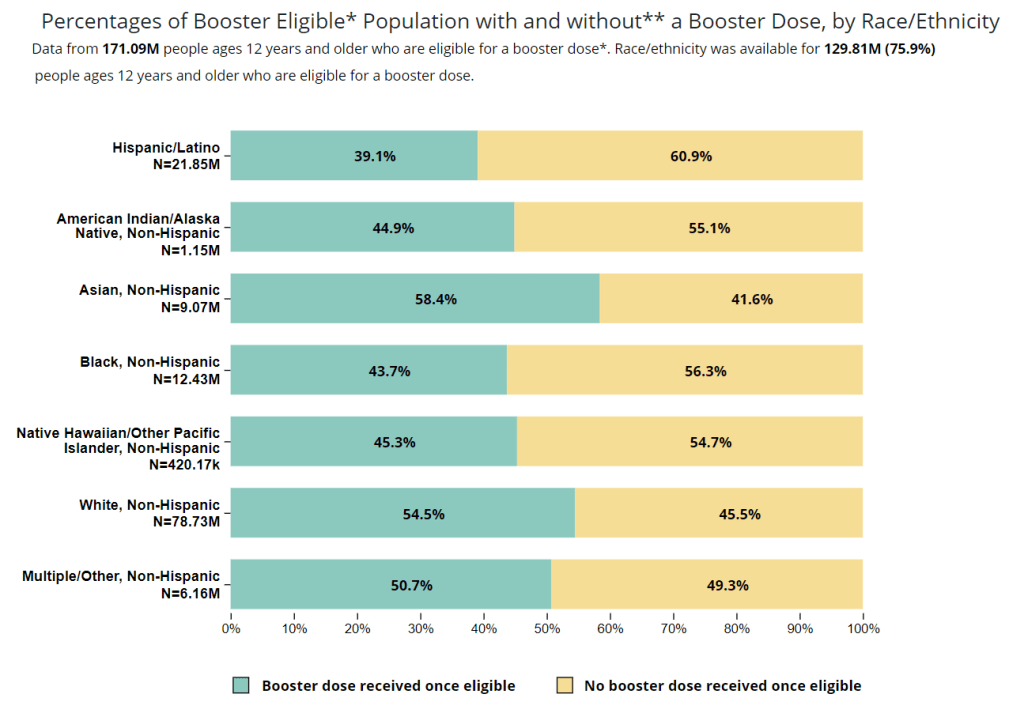

- Black, Indigenous, and other Americans of color, especially seniors: Despite dedicated vaccination campaigns and other health equity efforts, Americans of color have continued to be hit harder by the pandemic than white Americans. Higher rates of chronic conditions in minority populations combined with other socioeconomic factors (POC are more likely to work essential jobs, to lack healthcare, etc.) have led to disproportionately high hospitalization and death rates. And the U.S.’s booster shot campaigns so far have been inequitable, as shown in a recent study by demography experts. Reaching these populations should be a priority for the new Omicron boosters.

- Immunocompromised people: National estimates consider about 3% of Americans to be moderately or severely immunocompromised, meaning that their immune systems have limited capacity to respond to infections without medical assistance. This group includes cancer patients, organ transplant recipients, people with autoimmune diseases, and more. (This Yale Medicine article provides more information.) Immunocompromised people might have already had multiple booster shots but are still eligible to receive an Omicron booster as soon as possible, the CDC recommends.

- People with Long COVID and related conditions: While there isn’t as much established data in this area, I have seen a lot of anecdotal reports from Long COVID patients who work hard to avoid new coronavirus infections—concerned about reinfection’s possibility to worsen their symptoms. On the flip side, vaccination might lead to improvement in Long COVID patients, as the shot boosts a patient’s immune system in responding to lingering reservoirs of virus. The Atlantic covered this possibility when Long COVID patients were first eligible for vaccination in early 2021, and other studies since then have backed it up. More research is needed, but at the very least, Long COVID patients receiving a new booster will have lower risk of a new severe case.

- People with other preexisting health conditions: The CDC has an extensive list of medical conditions that can confer additional risk for severe COVID-19, with plenty of links to other CDC pages and medical sites where you can learn more about relevant evidence. I won’t go through them all here (that’s a topic for another week’s issue), but I do recommend checking out the CDC’s information and linked sources if you have a condition on the list. You can also explore this map of chronic condition rates by county.