The U.S. missed President Biden’s big vaccination goal: 70% of adults vaccinated with at least one dose by July 4. As of July 3, we are at 67% of adults with one dose, and 58% fully vaccinated.

I did a data-driven look at the vaccination goal this week in a story for the Daily Mail. The story focuses on which parts of the country have met the goal—and which areas fell short. Those under-vaccinated areas are highly vulnerable to the Delta variant (B.1.617.2), which is now spreading rapidly in many of those pockets. Reminder: the Delta variant is much more transmissible than even the Alpha variant (B.1.1.7), and its presence is doubling in the U.S. every two weeks.

There are over 1,000 counties in the U.S. with one-dose vaccination rates under 30%, CDC Director Dr. Walensky said at a press briefing last week. The U.S. has about 3,100 counties in total.

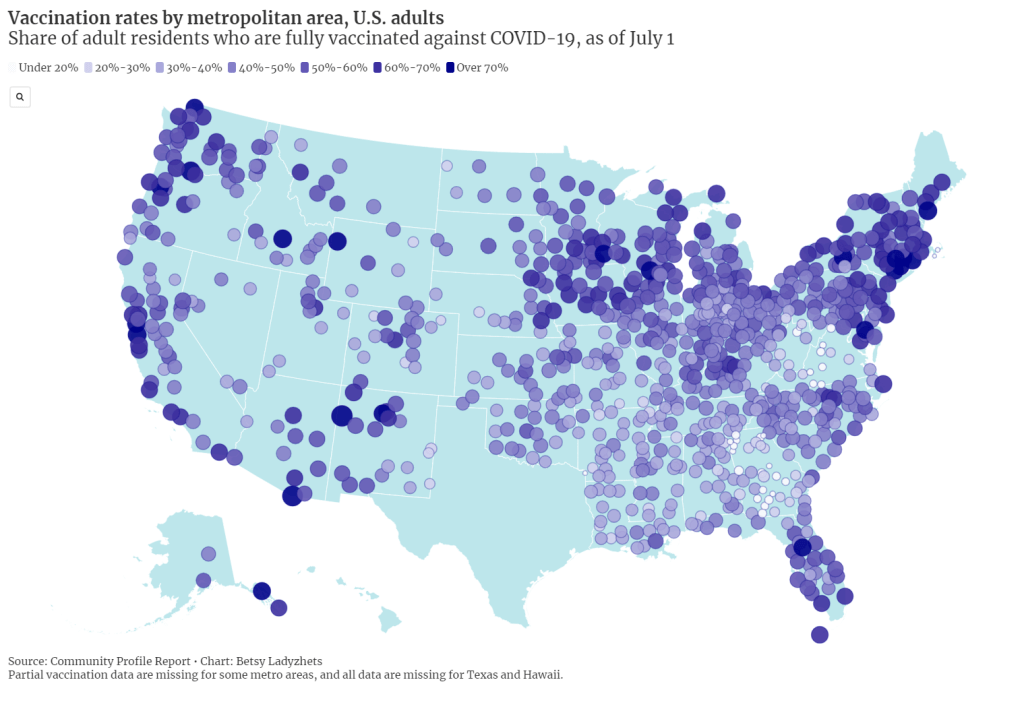

Is your county one of them? Check it out on this interactive map, reflecting data as of July 1:

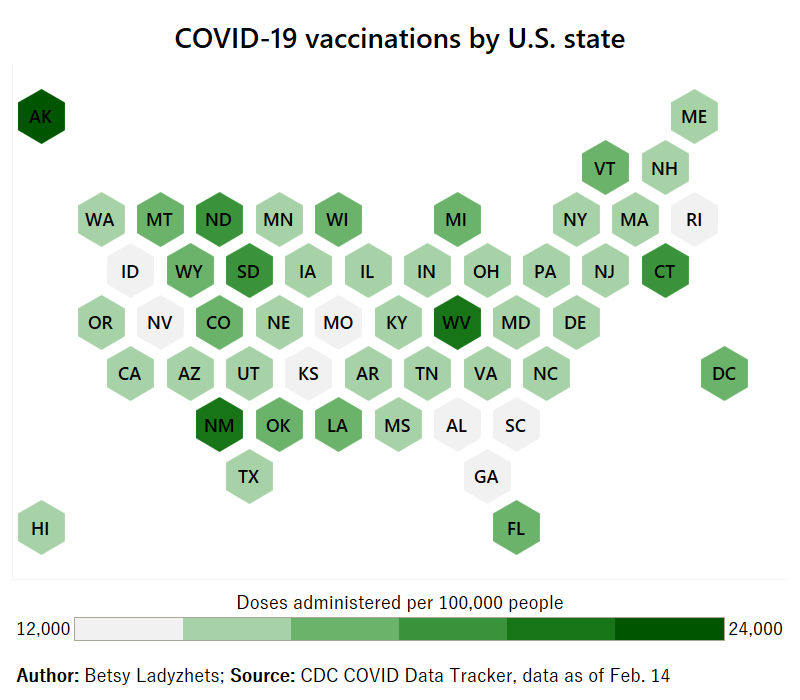

I also made a map showing vaccination rates by metropolitan area. You can clearly see clusters of high vaccination in the Northeast and on the West coast, while parts of the South and Midwest are under-vaccinated. Note that Texas is missing in both this dataset and the county-level data due to issues in the state’s reporting to the CDC.

For my Daily Mail story, I also asked two of the COVID-19 science communicators I most admire to explain the significance of that missed 70% goal. I talked to Dr. Uché Blackstock, physician and founder of the organization Advancing Health Equity, and Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, epidemiologist at the University of Texas and writer of the Your Local Epidemiologist newsletter.

Here are both of their takes on the missed goal:

So, we didn’t meet the 70% goal. It means that we fell short. It also means that we just don’t have enough people vaccinated, not even close, to reach herd immunity.

To me, as an epidemiologist, someone in the field and also someone within a community, it means that we have reached—or are about to reach—saturation [of the vaccine market]. We need to start becoming very innovative about how to address vaccine hesitancy, as well as how to address vaccine equity.

That’s really going to be the next phase of public health approaches. And then, how do we go about doing this… You know, we’re well beyond billboards now. We really need to mobilize a grassroots movement. We need to listen about concerns, we need to educate about these concerns.

And then, we need to make vaccines more accessible. Especially among pediatrics, where—pediatrician offices can’t store the vaccine. So we have to go to schools and really engage with families in a “nontraditional sense.”

Dr. Katelyn Jetelina

This 70%, especially for one dose, is sort of an arbitrary number, because we know that being fully vaccinated is what’s needed to fully protect you against variants. I think it was obviously wise and aspirational to have a goal. But at this point, because we’re basically seeing the number of people vaccinated decreasing weekly, and substantially since last April… I think we need to change our perspective.

We had the early adopters who came in droves to get vaccinated. We’re not going to see the same numbers anytime soon. And so, I think that this idea of having a goal, while it’s aspirational, I think that we have to put that aside and think more realistically about the challenges we’re dealing with.

And the challenges we’re dealing with are actually quite complicated… There are still access issues, although I do think the Biden administration is doing—at least trying to do a substantial job in knocking down those barriers. They’re providing transportation, childcare, increasing the access points for getting vaccinations, encouraging small businesses to offer their workers paid sick leave to get vaccinated and to recover from the vaccine.

But I think this other issue that we’re seeing among people who are not vaccinated, it varies depending on the population, the geographical area. We know rural populations are less likely [to get vaccinated]. And we know that, among the “wait and see” group, about half of those are people of color.

I hate to blame it on this so-called “vaccine hesitancy” because I don’t think it’s that simple. I do think, though, that there is a significant distrust of government, there is distrust of the healthcare system, and there is a lot of misinformation out there about the vaccines. All of these are essentially creating the perfect storm that is preventing us from getting to this aspirational [70%] number.

But here, we’re at this point where it’s a race against the variants, and I think that we just have to get as many people vaccinated as possible. I know that sounds incredibly vague, but that really is the goal.

Dr. Uché Blackstock

I made a third chart for today’s issue, visualizing vaccination rates by state from March through June. It really shows how vaccine enthusiasm has leveled off, just about everywhere in the country—but the plateaus started earlier in many of those states that have lower rates now.

I typically try to avoid anything approaching medical advice in the COVID-19 Data Dispatch, as I am a journalist with just an undergraduate biology degree and a couple of years of science reporting experience. But this week, it feels appropriate to wholeheartedly, unambiguously encourage vaccination.

I know the audience for a publication like this one skews towards people who probably have their shots already. Rather, I want to encourage you to find those people in your community who aren’t yet vaccinated, and help them take that step.

Recent research suggests that lotteries and other large-scale incentives do not significantly encourage vaccination; instead, we need small-scale incentives. One-on-one conversations with people, opportunities for concerns to be voiced and addressed, appointments that can be tailored to the individual’s needs. Anything that you can do to play a role in these initiatives, please get out there and do it.

Of course, if you (or your friends/family/community members/etc.!) have questions about vaccines, or anything else COVID-19 related, you know where to find me. Inquiries welcome at betsy@coviddatadispatch.com.

More vaccine reporting

- Sources and updates, November 12Sources and updates for the week of November 12 include new vaccination data, a rapid test receiving FDA approval, treatment guidelines, and more.

- How is the CDC tracking the latest round of COVID-19 vaccines?Following the end of the federal public health emergency in May, the CDC has lost its authority to collect vaccination data from all state and local health agencies that keep immunization records. As a result, the CDC is no longer providing comprehensive vaccination numbers on its COVID-19 dashboards. But we still have some information about this year’s vaccination campaign, thanks to continued CDC efforts as well as reporting by other health agencies and research organizations.

- Sources and updates, October 8Sources and updates for the week of October 8 include new papers about booster shot uptake, at-home tests, and Long COVID symptoms.

- COVID source shout-out: Novavax’s booster is now availableThis week, the FDA authorized Novavax’s updated COVID-19 vaccine. Here’s why some people are excited to get Novavax’s vaccine this fall, as opposed to Pfizer’s or Moderna’s.

- COVID-19 vaccine issues: Stories from COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers across the U.S.Last week, I asked you, COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers, to send me your stories of challenges you experienced when trying to get this fall’s COVID-19 vaccines. I received 35 responses from readers across the country, demonstrating issues with insurance coverage, pharmacy logistics, and more.