This week, The Hill posted an article with a rather misleading headline: “CDC finds less than 1 percent of fully vaccinated people got COVID-19.” If you actually click into the piece, you’ll find that the precise number is less than 0.008%. Less than 0.0005% have been hospitalized and less than 0.0001% have died.

This headline reflects a common issue with vaccine reporting that I’ve seen in the past few weeks. A lot of journalists, especially those who aren’t familiar with the science/health beat, may be inclined to publish news of breakthrough cases as surprising or monumental. In fact, these cases—referring to a COVID-19 infection that occurs after someone has been fully vaccinated—are entirely normal, yet incredibly rare.

No vaccine is perfect. Even the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, which both demonstrated 95% efficacy in their late-stage clinical trials and over 90% effectiveness in the real world, are not perfect. Scientists still expect a few COVID-19 infections to slip through the immune system defenses built up by these vaccines and cause illness in a small number of patients.

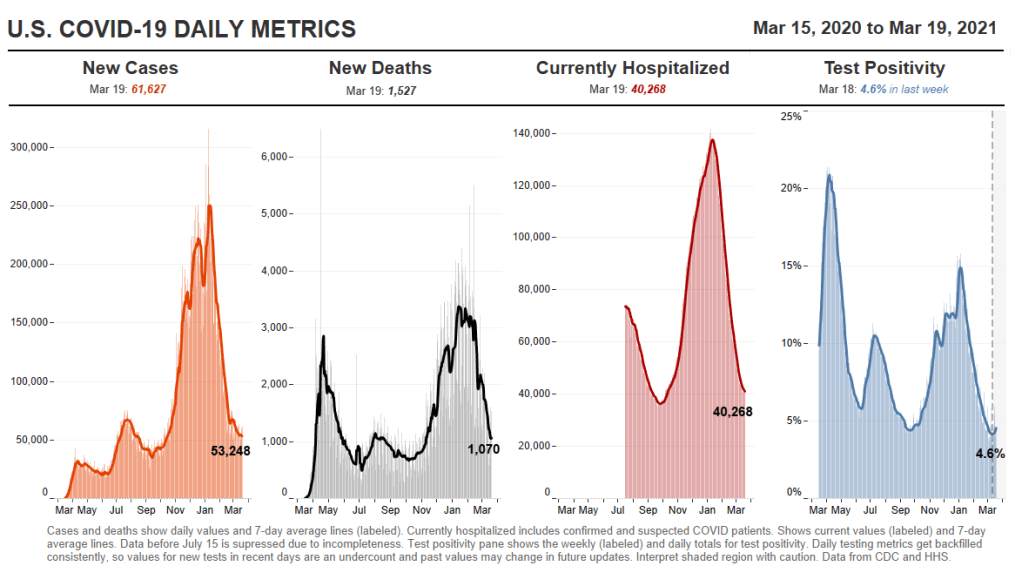

And it really is a small number: 129 million Americans have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine as of yesterday, per the CDC, and 82 million have been fully vaccinated. The agency has only documented 5,800 breakthrough cases. Less than 0.008% of those people who have been fully vaccinated. That’s the equivalent of one-quarter of a seat in Queens’ Citi Field baseball stadium (which seats about 42,000).

So, if you’re a journalist reporting on this issue—whether it’s nationally or in your community—it’s important to stress that denominator. 82 million fully vaccinated, 5,800 breakthrough cases. Emphasizing the difference in magnitude between these numbers can show readers that, while they should still maintain some caution after getting vaccinated, the vaccines are overwhelmingly safe and effective.

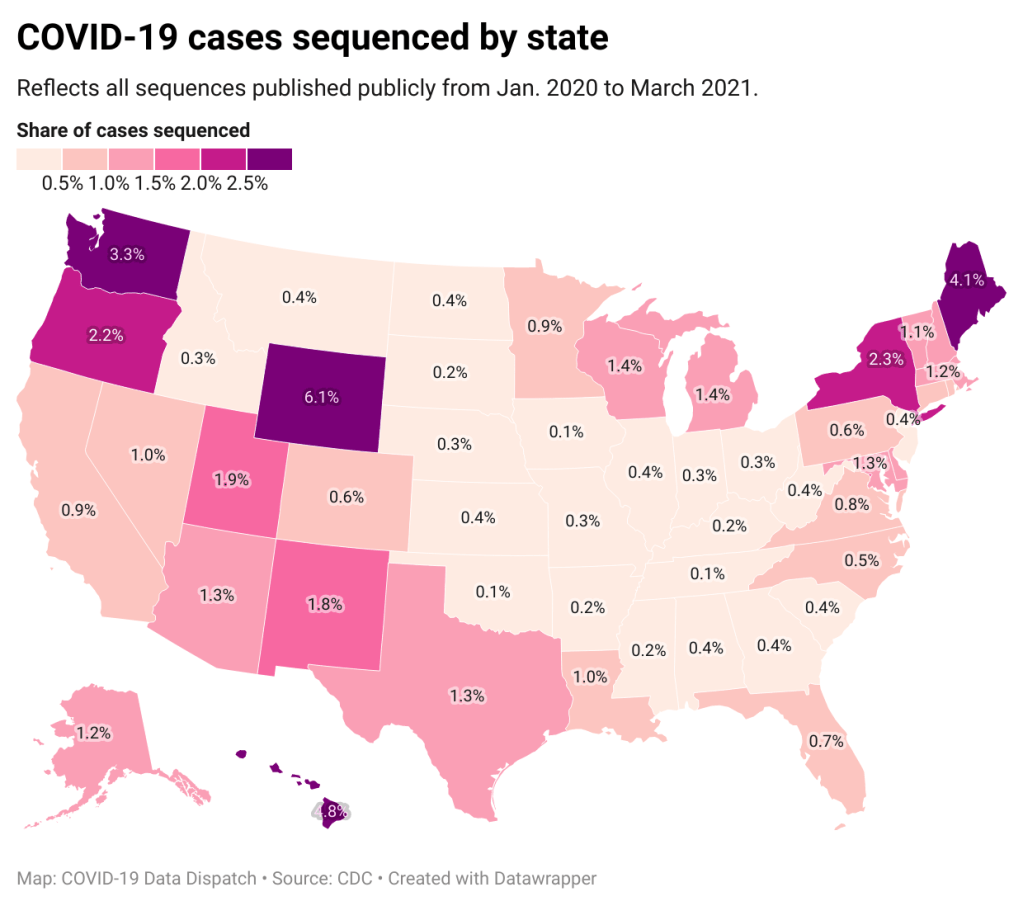

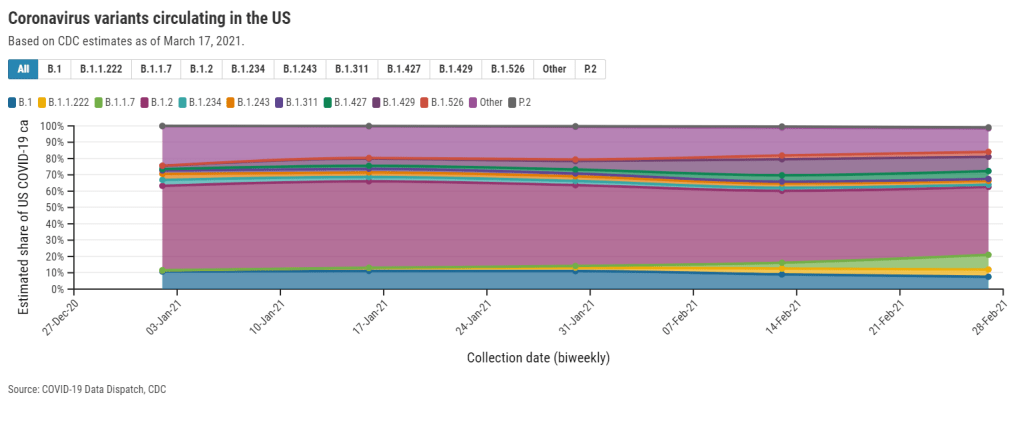

Small as the breakthrough case numbers are, though, it is important that we still talk about them. A new article by ProPublica’s Caroline Chen discusses how a failure to collect data on breakthrough cases is making it harder for COVID-19 researchers to understand what causes them. Specifically: we should be sequencing the genomes of the coronavirus strains that caused these cases, and by and large, we aren’t.

Chen describes how many state health departments aren’t getting breakthrough case samples to sequence, whether that’s due to testing labs failing to store the test samples or cases being identified through rapid tests, which do not have established pipelines. Plus, in some cases, we aren’t even recording whether the patients went to the hospital or died—key data points in the U.S.’s continued vaccine monitoring.

I definitely recommend you read the full piece, but here’s a section that will give you the big idea:

In many instances, patients’ samples are not sequenced to find out if a variant might have been involved; some labs are throwing out test samples before an analysis can be done; hospitals and clinics aren’t always collecting new samples to analyze them. That means that for so many people, nobody will ever know if a variant was involved, leaving public health officials without data to be able to examine the extent to which variants are contributing to breakthrough cases.

“It’s alarming that we can’t sequence more of the virus than we’re able to now — that’s something we need to resolve,” said Brian Castrucci, chief executive officer at the de Beaumont Foundation, a health philanthropy. “The more we know, the better we can react. We want to know the information so that we can make the right policy and health decisions.”

While the CDC has an info page on breakthrough cases, no data on these cases are available on the agency’s COVID-19 dashboard. Reporters need to walk a delicate line on this issue: pursue the data, but report it in a careful, conscientious way that appropriately puts the tiny breakthrough case numbers in context.

More vaccine news

- Sources and updates, November 12Sources and updates for the week of November 12 include new vaccination data, a rapid test receiving FDA approval, treatment guidelines, and more.

- How is the CDC tracking the latest round of COVID-19 vaccines?Following the end of the federal public health emergency in May, the CDC has lost its authority to collect vaccination data from all state and local health agencies that keep immunization records. As a result, the CDC is no longer providing comprehensive vaccination numbers on its COVID-19 dashboards. But we still have some information about this year’s vaccination campaign, thanks to continued CDC efforts as well as reporting by other health agencies and research organizations.

- Sources and updates, October 8Sources and updates for the week of October 8 include new papers about booster shot uptake, at-home tests, and Long COVID symptoms.

- COVID source shout-out: Novavax’s booster is now availableThis week, the FDA authorized Novavax’s updated COVID-19 vaccine. Here’s why some people are excited to get Novavax’s vaccine this fall, as opposed to Pfizer’s or Moderna’s.