It’s been a minute since I last did a Delta variant update, and this seemed like a good week to check in. Here are a couple of major news items that I’ve seen, along with sources where you can read more.

The Delta variant continues to be highly transmissible. On August 1, I wrote that an interaction of a few seconds is enough for Delta to spread from one person to another, when both people are unvaccinated and unmasked.

All the new evidence that we have on Delta outbreaks backs up its incredible ability to spread. For example, in a California elementary school, an unvaccinated teacher spread the coronavirus to 12 out of the 24 students in her class, with students sitting closer to the teacher more likely to be infected. The classroom outbreak led to 27 cases in total, including the teacher—who worked for two days after first reporting her symptoms. All the cases were identified as Delta.

Growing evidence points to Delta being more severe. A recent study in The Lancet from epidemiologists in the U.K. suggests that Delta causes severe disease more frequently than the Alpha variant (B.1.1.7). The researchers looked at hospitalization rates for British COVID-19 patients, finding that patients with Delta were twice as likely to require hospital care compared to those with Alpha. Delta patients were also younger, on average—though this could be conflated by high vaccination rates among British seniors.

Commenting on this study in Your Local Epidemiologist, Dr. Katelyn Jetelina writes:

This adds to the growing evidence that Delta is more severe. An early Scotland study found that the risk of hospitalization was nearly double than previous variants. An early Public Health of England technical report found this too. We also saw this in Singapore where Delta infection was associated with higher risk of oxygen requirement, ICU admission, or death.

For kids, higher hospitalization rates are tied to community vaccination, not Delta severity. This Friday, the CDC released two reports on COVID-19 hospitalization in children.

One major finding: out of all children with COVID-19 cases, the proportion of kids who have a severe case has not increased from previous surges to this current Delta surge. Prior to June 2021, about 27% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients under age 18 required ICU admission; in late June and July (during the Delta surge), that number was 23%. Also, the average hospital stay was shorter during the Delta surge than previously (1-4 days compared to 2-5 days). These statistics indicate that Delta isn’t more severe for kids—rather, we’re seeing cases in such high numbers that it drives up hospitalizations.

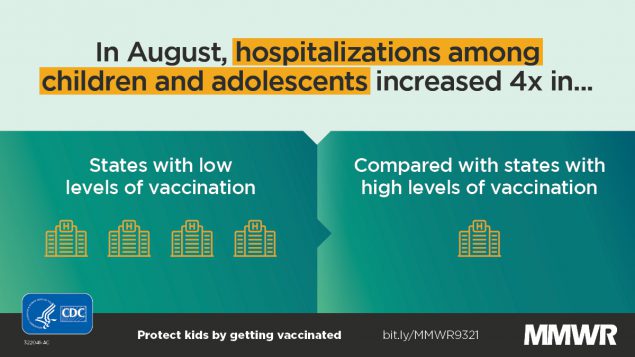

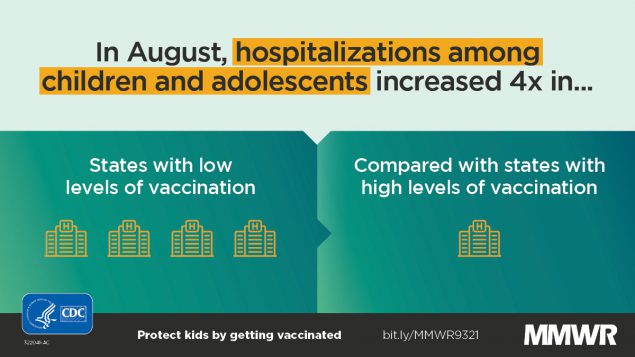

According to the CDC’s other Friday report, hospitalizations among children (under age 18) were four times higher in states with low vaccination levels compared to states with high vaccination levels. In other words: vaccination is crucial not just to protect yourself from severe COVID-19, but to lower community transmission and protect young children who can’t yet be vaccinated.

Evidence for boosters continues to be questionable. After the Biden administration announced that the U.S. plans to provide third vaccine doses to everyone who received Pfizer or Moderna’s vaccines, I wrote that evidence and transparency on this decision were lacking. The situation hasn’t changed much; while studies show that COVID-19 antibody levels decline several months after vaccination, many experts are not convinced that boosters are necessary for everyone at this point.

If immunity is “waning,” why don’t we need extra shots? As usual, Katherine Wu at The Atlantic has a great article explaining the complexities here. Here’s a key paragraph from her piece:

Defensive cells study decoy pathogens even as they purge them; the recollections that they form can last for years or decades after an injection. The learned response becomes a reflex, ingrained and automatic, a “robust immune memory” that far outlives the shot itself, Ali Ellebedy, an immunologist at Washington University in St. Louis, told me. That’s what happens with the COVID-19 vaccines, and Ellebedy and others told me they expect the memory to remain with us for a while yet, staving off severe disease and death from the virus at extraordinary rates.

In short, though antibody levels may drop, that represents just one measurement of the immune system’s ability to fight COVID-19. Other parts of the immune system will remain ready to address the coronavirus for long after an individual is vaccinated—you just might be more likely to have an asymptomatic or mild case, rather than avoiding infection entirely. (One big caveat here: We don’t know much about the risk of Long COVID after vaccination.)

In fact, both Rochelle Walensky (CDC director) and Janet Woodcock (interim head of the FDA) are reportedly “pushing back on the White House’s plan” for booster shots, saying they need more time to collect and review data. I, for one, hope all of their data — and discussions — are made public in the coming weeks.