I recently had the opportunity to discuss data equity with Dr. Debra Furr-Holden, a public health expert at Michigan State University. Dr. Furr-Holden is the university’s Associate Dean for Public Health Integration and Director of the Flint Center for Health Equity Solutions, a health research center focused on Flint, Michigan, where she is based.

At one of my National Science-Health-Environment Reporting Fellowship training sessions, Dr. Furr-Holden spoke about the Flint water crisis and other health equity issues. Her comments made me think about continued issues in COVID-19 data collection and reporting, so I asked her to discuss COVID-19 data further in an interview for the CDD.

We talked about the ongoing challenges of collecting and reporting COVID-19 race data, how data gaps fuel vaccine hesitancy, the equity challenges inherent in vaccine mandates, and more.

The interview below has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Betsy Ladyzhets: First, I’m curious about your backstory, how you got involved in doing this kind of [health equity] work.

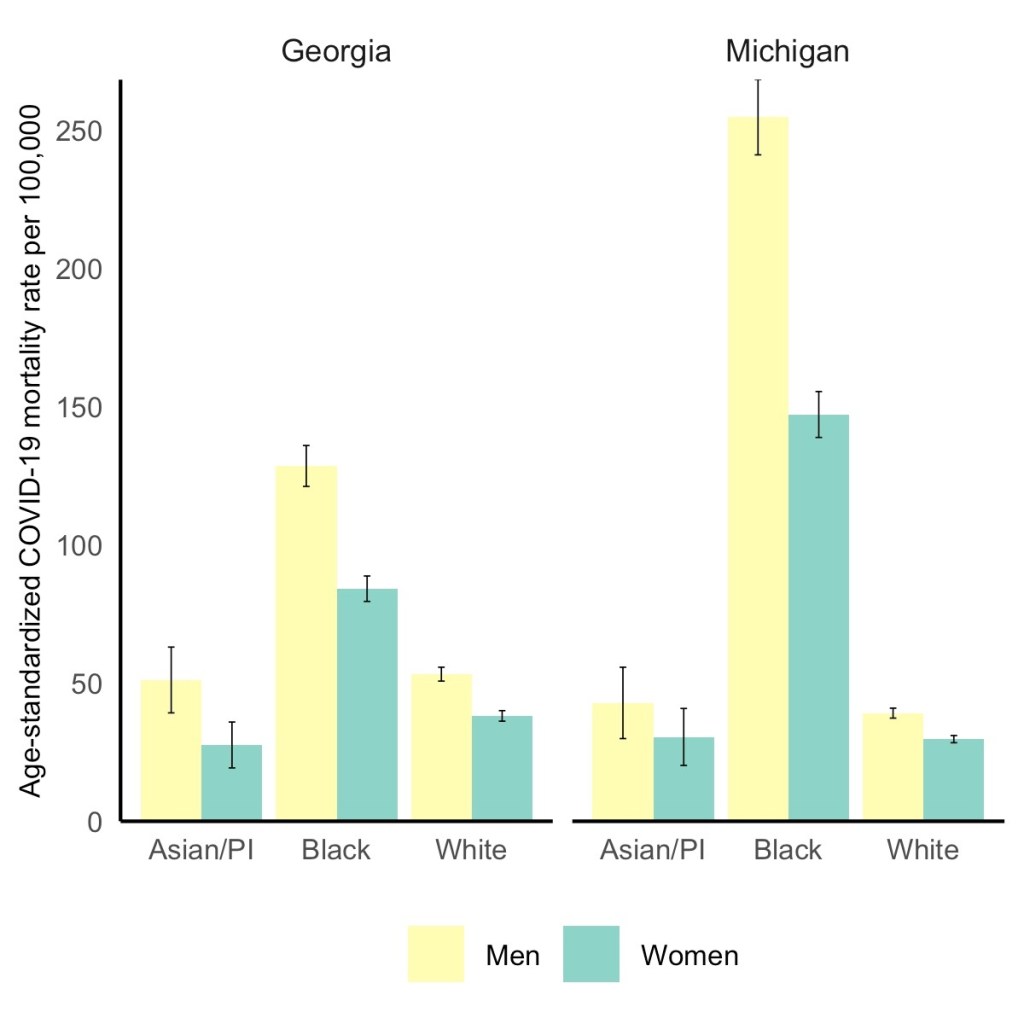

Dr. Debra Furr-Holden: I think it probably was born out of my own lived experience. My dad died at 37, of a complication from hypertension. My mom died at 56 of an asthma attack.

It wasn’t until I went to college that I realized that my peers had very different experiences. I went to college with no living grandparents and one living parent, and I just assumed everybody had relatives with, you know, amputated limbs and with diabetes and heart disease. And I realized that’s not the case.

As I networked with the very small cohort of African-American students in my class, I noticed despite our socioeconomic backgrounds—because I came from sort of more humble beginnings than some of my Black and brown peers—I was like, Oh, [these health conditions are] over-represented in black and brown people.

BL: How has that informed the work that you’ve been doing with COVID? I saw that you’ve been advocating for better vaccine access and stuff like that?.

DFH: What I’ve realized is, a lot of what we do around disparities, we do to people, and for people, and on their behalf. But the populations most affected very rarely have a voice, and the solutions that get created and implemented and employed—and we saw it with COVID, we’re seeing it now.

The President has made a national declaration, give everybody $100 for the newly vaccinated. And that doesn’t make sense to a lot of people. People who are having trouble paying for their hypertension medication or their other things are now being told, we’ll give you $100 to get this COVID vaccine. When earlier in the pandemic, those same people couldn’t get access to a COVID test.

BL: And in some cases, probably still can’t get access to a COVID test.

DFH: Yeah. And I’ve just realized, like, my own lived experience that is ongoing still informs my work, but it elevated my authentic and deep appreciation for how important the voice of community and affected populations is in the work. It’s not just about the data. It’s not just about the science… You can only glean but so much from a data table. You need more wind underneath that. And that wind is the voice of community, and the voice of the people that you’re trying to impact and serve.

So, the big gap to me in our work around how to bridge this gap among the unvaccinated is: we are quantifying who is unvaccinated, but we’re not asking the question of, what is needed to bridge that gap for you to get the vaccine? Instead, I think we’ve got a lot of well-meaning people who are coming up with solutions, but those solutions are not mapping onto people’s concerns. And it’s not moving the needle.

In Ohio, they offered this big lottery, it did not cause a big boom in vaccination. Same thing is happening in Michigan right now. It did not rapidly accelerate the pace of newly vaccinated people. And because my work is so community engaged, when I talk to people and they tell me the reasons underneath [their vaccination choice], it’s not about the money.

I call the money the carrot. We’ve tried to dangle the carrot in front of people. That didn’t produce much. Now we’re using the stick.

BL: The mandates.

DFH: The mandates, yeah. That will likely produce more [vaccination] than the carrot did, because people will have their hands forced. But that will likely elevate resentment and give way to—any negative consequences or outcomes that come from people being forced into vaccination will likely only further fuel their mistrust of the healthcare system, and our government overall. I just feel like the solutions are not being informed by the people that we’re trying to get on board.

BL: Yeah. What kind of information do we need to actually inform better solutions, do you think?

DFH: We need to hear from the very large and diverse pool of unvaccinated people. Because there’s no one solution here.

Now, I do believe fundamentally, as a public health professional, I think of public health big population-level interventions that make health choices easy. So things like fluoride in drinking water. We don’t [remember] the time when the cavities and dental cavities were contributing to all of this excess death and morbidity. Why, because we got fluoride in drinking water. So it’s just a non-starter for us now. Same thing for standardized childhood immunizations, which were transformative for eradicating diseases that took millions of lives before we not only developed those vaccines, but made them a part of the standard immunization protocol for children.

We’ve now got to do the work to figure out how to implement and integrate these COVID protections into our system of care, and have them be more normative. I think all of the mistakes around how the whole pandemic has been handled in the US—how the resources, not just the vaccine, but other resources, like payroll protection, enhanced unemployment, support for essential workers.

You know, we weren’t providing PPE to essential workers in the beginning. We had national leaders saying you don’t have to wear a mask. All of these things now conflict with, “Oh, we care so much, and everybody has to get vaccinated. Everybody needs to take one for the team.” People just aren’t buying into that.

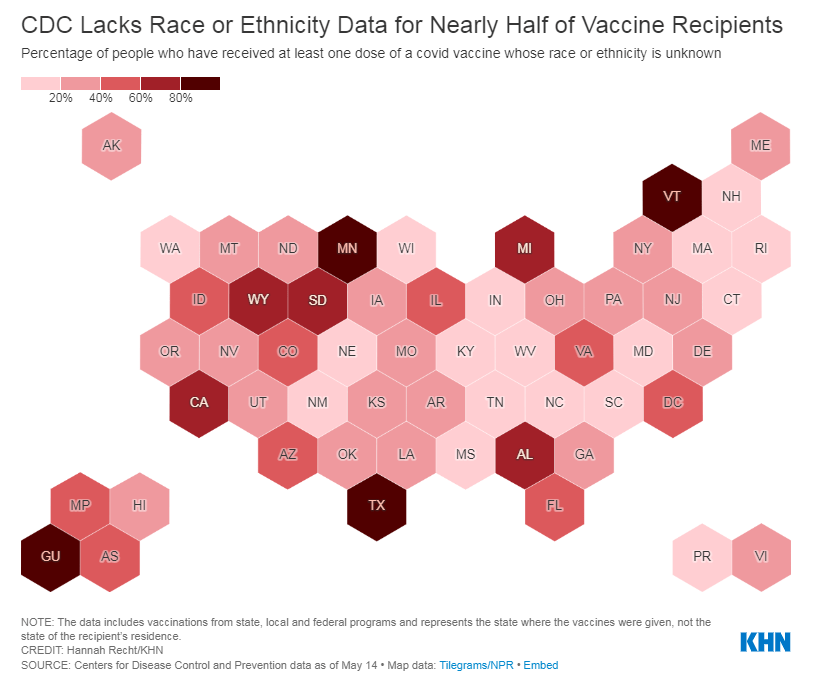

BL: They think there’s something else going on, I guess. So, I know, when we were closer to the start of the vaccine rollout, like earlier in 2021, I saw a lot of press attention on the lack of demographic data on vaccinations. A couple of my colleagues at the COVID Tracking Project wrote an article in The Atlantic and there was other kind-of big name publication stuff. But now we still don’t have good data. And it seems like no one is really drawing attention to that. I’m wondering if you have any thoughts on this, and if there’s anything we can do to continue that pressure, because we still do need this information.

DFH: Yeah, it’s unfortunate, because I always say a lack of data continues to fuel the debate. And the lack of quality data around COVID resources is only fueling the problem. It is an unnecessary and unacceptable omission for providers to administer COVID tests and not collect basic demographic data on the people that they’re testing. It dampens our ability to quantify who is most impacted and what should be the targets of our outreach, engagement, and intervention efforts. And it’s unnecessary and unacceptable.

In Michigan, the system that we use is called MICR… It would take a programmer about eight seconds to make race, and ZIP code, and gender, and age category a required field to be entered. And we just simply haven’t done it. And so as a result, it’s hard for us to quantify the extent of a problem.

Because, remember, COVID cases are only a function of COVID testing. You can only get identified as a COVID case as a function of having a COVID test. If you’re in a household, and there’s a known case in the household, and all of the other [household] members display classic COVID symptoms, if they don’t get a test, they don’t get counted anywhere. So we know that we’ve greatly underestimated the extent of the problem.

BL: When I asked you about this at the SHERF session, you mentioned that there’s a provision in the CARES Act that requires providers to do this [data collection]. Can you talk more about that? And what we can do to actually have some accountability there?

DFH: Yes. There is a provision in the CARES Act that all COVID testing providers have to collect these core demographic variables. And then there was follow up guidance that was issued. And when the new administration took office, they haven’t enforced that [guidance].

So COVID testing providers continue to receive these resources to provide COVID testing, with no quality assurance or quality control, to ensure that they’re actually collecting and entering that demographic data. It then shifts the responsibility to backfill that information to local health departments and other providers, to try to link insurance records or electronic health records. Or even worse to do outreach and contact tracing and actually contact cases, by phone or by email to try to backfill that information. When there are so many other competing demands, it’s an unfair and undue burden to place on an already overstressed segment of our healthcare system.

What it’s akin to is gums without teeth. We have the law, but there’s no enforcement or compliance checks to ensure that that law is being honored. And I think a simple solution is compliance checks. We need compliance checks, and we need enforcement.

BL: Do you have any thoughts on other stories that we should be telling? Like, what should I tell my journalist friends to cover around COVID and health equity?

DFH: One thing is probably already on your radar, which is the fact that we’re not doing systematic genetic sequencing on current strains of COVID. So it’s hard to estimate, you know—people keep talking about the Delta variant, but we have thousands of variants of SARS-CoV-2 now. And we just don’t have a good system for genomic surveillance to understand them.

And the CDC a few weeks ago said, we’re just going to stop doing the genomic sequencing on any kind of systematic level and reporting. It’s a problem, because with breakthrough cases, and

the vaccinated now showing up in hospitals and emerging data saying that even if you’re vaccinated, you can still spread and transmit… I just had a conversation with somebody who works in our building who said, I don’t want to get vaccinated, because if I get COVID, I want to have symptoms, so I’ll know, so I can protect my nine-year-old who’s got asthma. Like, I want to know. A lot of people now feel like the vaccine increases the chances of them being an asymptomatic carrier.

We just really have to collect data. Instead of mandating shots in arms, we should be mandating the data so that we have better information and can do more credible and transparent information dissemination to communities.

BL: Yeah, so that we can actually answer people’s questions on these things.

DFH: Yeah.

BL: I was also wondering if you had any recommendations, either of good stories that do a good job of covering these issues we’ve been talking about, or data sources or resources that myself and other journalists in this space should be paying attention to.

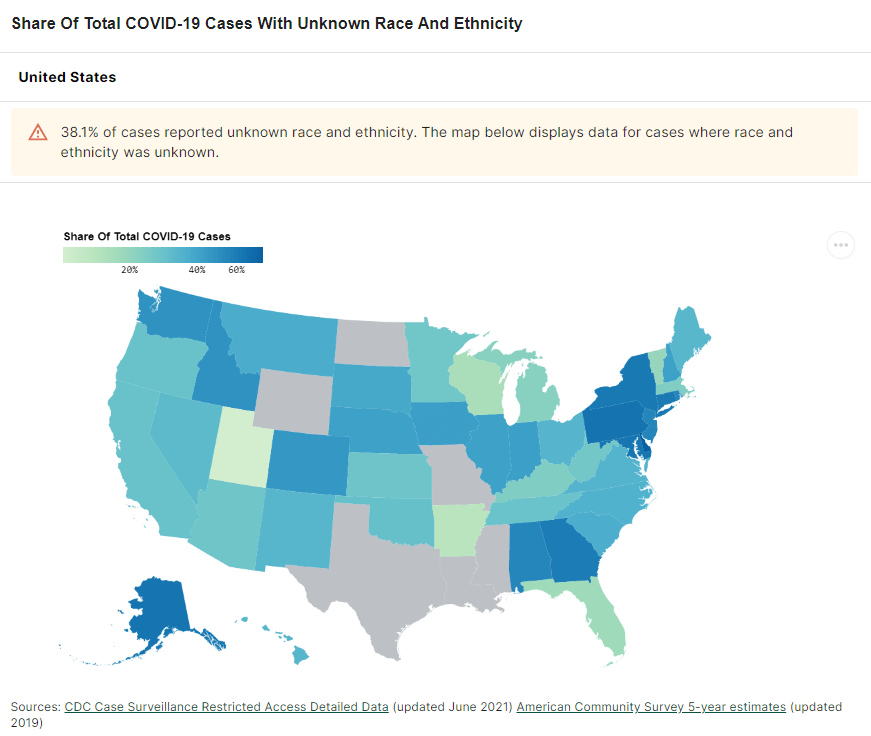

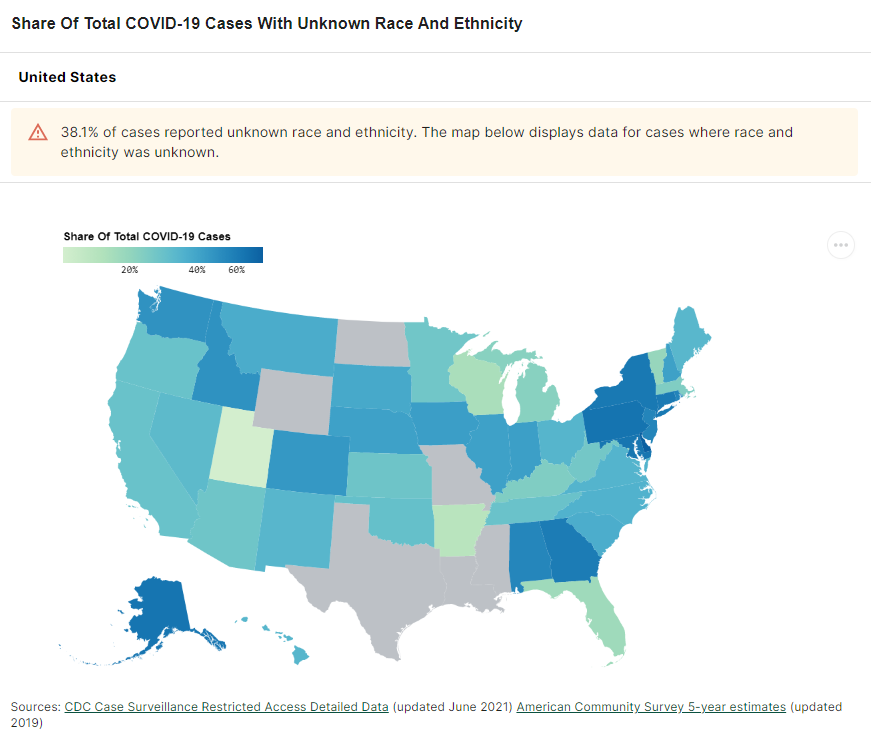

DFH: We should be putting the press on the CDC to collect and compile the data. Like, the data on cases, all of that data should be disaggregated by race. And the percentage of cases with unknown race or unknown gender or unknown geography should also be reported. Because I don’t know if people notice this, but a lot of times [the CDC is] presenting data only on cases with complete information. But the missing information points to something important as well.

BL: I think it’s something like they have maybe 50% or 60% of cases with known race. But where’s that other share of cases? [Editor’s note: It’s 63%, as of August 14.]

DFH: The assumption is that the distribution of these variables in the unknown is similar to that of the known. But it is a major assumption. And it’s not an assumption that we should be making.

BL: I see. Yeah. Anything else [you’d recommend as a story idea]?

DFH: I do like this carrot stick analogy. The carrot is not working, the dangling the big incentive is not working. The stick will likely work. If you tell people, “You can’t get on a plane, if you’re unvaccinated,” there will be a lot of people who are unvaccinated right now who will get vaccinated because they’ll not want to lose the opportunity to travel.

Think about the media. If you are chasing a story, or if you’ve got to be on site for something… If you’re in New York and you’ve got a story in California, you’re not going to drive to California, you will likely get off the fence and get vaccinated.

I feel like a larger problem is, we have to engage experts in the work to make sure that we’re not furthering inequity [with mandates]. Because if we use, now, the stick, and start to mandate it…. [Michigan State University] has now mandated vaccination for all faculty, staff and students who want to return to campus by September 7. I know that that will likely produce greater increases in vaccination than did the incentives of cash payments, or lotteries or other things.

But we have to keep an eye toward equity, and make sure—what if there’s disproportionality and then who does that impact? Are we going to see an increase in Black and brown people, or people with disabilities, or people with chronic health conditions, losing their jobs, or dropping out of school, or some of these other things? There just needs to be more thoughtfulness to how we apply these policy interventions to make sure that it’s not furthering inequity.

BL: Have you seen any examples of where that’s been done successfully?

DFH: No, because it’s all just coming out now.

BL: I know there are some places, like in New York, they’re giving you an option, saying, “You can get vaccinated or you have to be tested once a week.” Is that effective? Or does that still fit into what you’re talking about?

DFH: I think we’re gonna figure that out. And if that’s the case, then again, we gotta deal with the access issue, and people need to have fair and equitable access—and affordable access—to COVID testing.

BL: Yeah, totally. And the last kind of big question I had for you: one thing I think a lot about as a journalist who is still rather early-career and has been covering COVID very intensely is that this is probably just the beginning of us dealing with major public health crises. You know, continued climate disasters and all that stuff.

And I’m wondering how you think about preparing for the next COVID, or the next whatever it’s going to be. What lessons do we take from these past couple of years?

DFH: Well, I think we’ve learned there is a business case for preparedness, and a business case for equity. Our lack of preparation for this pandemic will have cost our country tremendously. There’s going to be tremendous financial toll. So, there’s a business case to be made for preparedness.

We learned that with the Flint water crisis. Not having the million-dollar investment in the water treatment system, not spending the 150 bucks a day on anticorrosives, those things will have cost us hundreds of millions of dollars to now replace and repair the whole water infrastructure system and pay settlements from the Flint water crisis.

And then there’s also a business case for equity. Not doing a better job of equitably rolling out the vaccine early on caused a lot of people who were a “yes” to sort of say, “why bother?” And now many of them are a “no.” These are people who earlier on [were amenable], but then all these reports come out and get sensationalized by the media of side effects and blood clots and heart inflammation. And so a lot of people who were in line, trying to move through the line to get vaccinated are now an absolute “no.”

That’s going to cost us as well, because we have fallen well short of that 70% goal. And new vaccinations are moving at a snail’s pace. So I think what we’ve learned—and we’ll really know, the impact of it in the next few years—is not being prepared and not practicing equity will have a tremendous financial toll on the country.