By Miles W. Griffis

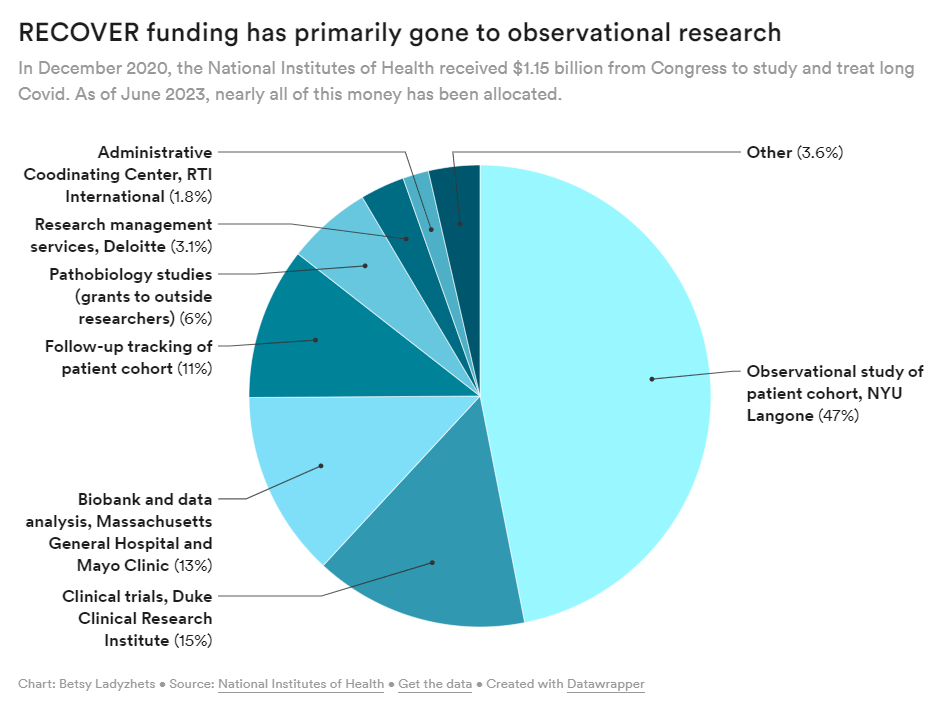

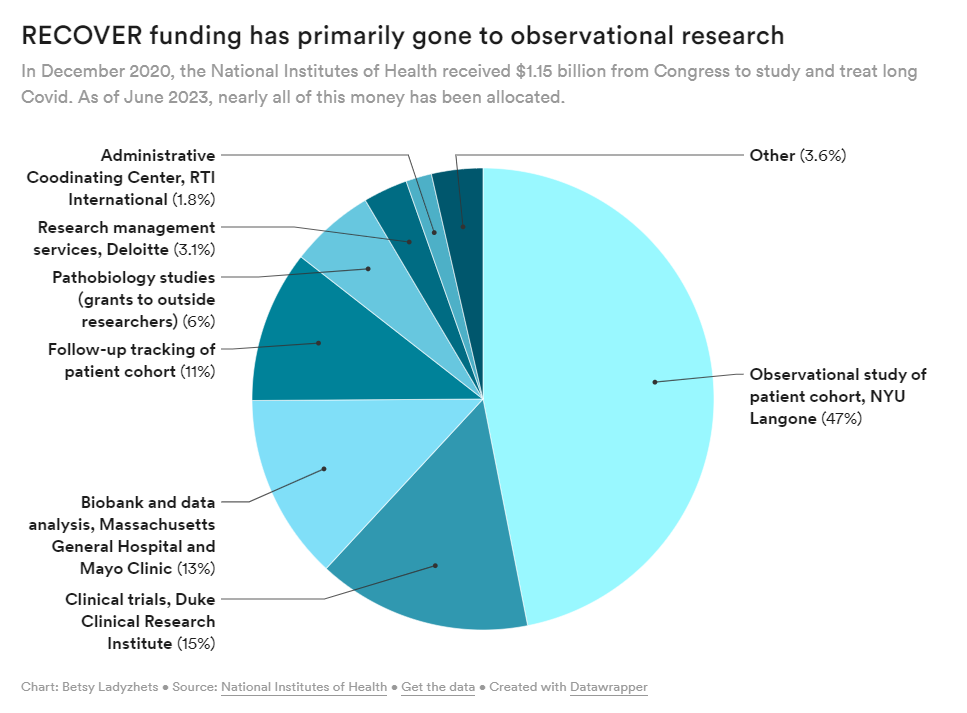

The National Institute of Health (NIH) is under fire for censoring comments from patients on social media — the latest in a trend of heavy criticism from people living with Long COVID for failing to listen to patients and implement their input into its $1.15 billion study, RECOVER. Patient concerns have been echoed by both scientists and healthcare professionals who have criticized the study’s lack of results, glacial pace, potentially harmful clinical trials, and wasted funds.

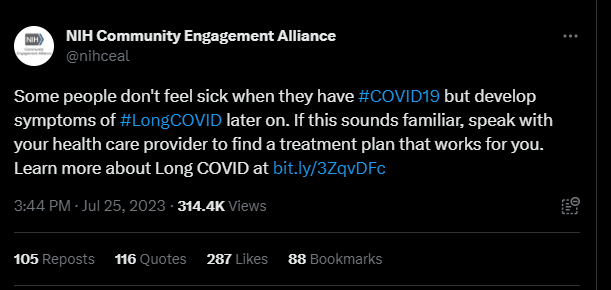

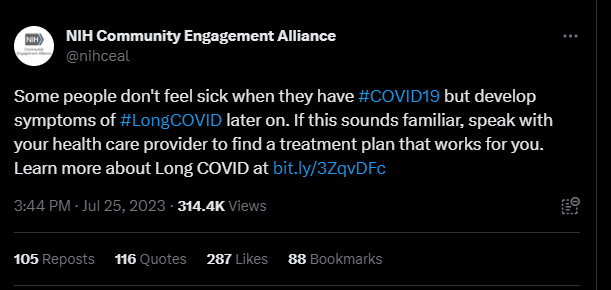

Last month, the NIH Community Engagement Alliance (NIH CEAL) tweeted, “Some people don’t feel sick when they have #COVID19 but develop symptoms of #LongCOVID later on. If this sounds familiar, speak with your health care provider to find a treatment plan that works for you.” The controversial tweet received over one hundred responses, many from people with Long COVID and other infection-associated illnesses.

Patients claimed the post contained misinformation about Long COVID treatments, as this debilitating multi-systemic condition affecting millions does not have any approved treatments or cures. Other commenters shared their negative experiences with their primary health care providers, who they say didn’t offer them any treatment plans or worse, gaslit them and wrote their symptoms off completely. Over 35 of these comments were hidden by the NIH CEAL account.

When asked about this comment hiding, the NIH told me that their social media policy was “overapplied” and that comments on the post were “inappropriately hidden.”

Olenka Sayko, a person with Long COVID whose comment was hidden, said the censorship added to a feeling of hopelessness: “Are we ever going to find solutions for Long COVID if patient voices aren’t being listened to?” She said the censorship is especially concerning since it came from an NIH account dedicated to community engagement. “Who are they engaging with? They’re hiding comments.” Lauren, another person with Long COVID who also was censored, said that the NIH CEAL’s tweet rhetoric sweeps Long COVID and the people experiencing it “under the rug.”

NIH CEAL clarified their tweet earlier this month. “While there’s no cure for Long COVID,” the new post read, “there may be treatment options that can address one’s symptoms & may help people living with Long COVID have better days.”

Although there are no treatments or cures for Long COVID, there are some treatments for conditions associated with or triggered by COVID-19 or Long COVID, including dysautonomia, cardiac disease, diabetes, and others. Many healthcare professionals recommend that patients who have prolonged symptoms following COVID-19 should be screened for life-threatening medical events that can be caused by COVID-19 or Long COVID, including pulmonary embolisms, deep vein thrombosis, or strokes. Long COVID can be fatal. A CDC analysis found that more than 3,500 people have died of the condition, though many experts believe this is a vast undercount.

And while there are many Long COVID clinics around the country that may give the illusion of successful treatment plans, patients often don’t have successful experiences. In an article I wrote for Popular Science, I found that some clinics recommend potentially harmful treatments like graded exercise therapy. Others rejected and gaslit patients. Some only offered generic informational handouts.

During an August 31 NIH RECOVER press conference, the director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), Walter Koroshetz, responded to my question about what Long COVID treatment plans the NIH CEAL account was referring to. He said that the NIH does not make treatment recommendations, adding that the NIH CEAL tweet might have been a misunderstanding. When I asked why the agency was censoring tweets from Long COVID patients, Lawrence Tabek, the acting director of the NIH, said he couldn’t speak to my question and said he has “no idea how social media works”.

I later followed up with the NIH over email about the censored comments. The agency wrote that “The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) co-manage the NIH Community Engagement Alliance (CEAL) social media accounts and follow the NHLBI Privacy Statement and Comment Policy.” The policy states commenters should post “on topic,” “be respectful,” and “truthful.” It also prohibits spam and product endorsements.

The NIH wrote over email that, in the case of the censored comments on the July 25th tweet, their policy was “overapplied” and that comments on the post were “inappropriately hidden.” They added that upon further review, comments on the post are now “public,” or unhidden. Some comments, however, were still hidden at the time of publication.

But Eric Goldman, the co-director of the High Tech Law Institute at Santa Clara University School of Law, said this very policy may not be even constitutional. “Assuming that the NIH is a state actor, then anytime they take an action on social media to control the conversation, their decisions are governed by the First Amendment, which protects our right to free speech,” he said.

Instances like the NIH censoring comments on social media are complicated, but upcoming Supreme Court cases may provide some clarity, Goldman said.

Two cases, Lindke v. Freed (from the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals) and Garnier v. O’Connor-Ratcliff (from the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals) may be heard by the Supreme Court this fall. Both involved government officials blocking members of the public on social media, but each led to a different result. The 9th Circuit found impermissible censorship, while the 6th Circuit did not. Due to the complexity of internet law, it’s unlikely Americans will feel good about the rule of law that will be articulated by the Supreme Court,” he said.

Still, if the NIH is “selectively listening to people online, then that’s hugely problematic,” Goldman said. In particular, the NIH could be denying the patients’ ability to learn and talk with each other. “Selective intervention by the NIH takes away that potential,” he said.

Advocates say the censorship has further eroded trust between the Long COVID community and the NIH. “It’s not just a one off,” Billy Hanlon, the director of advocacy and outreach for the Minnesota ME/CFS Alliance said, “It’s a pattern.” The agency fails to value the lived experience of patients with infection-associated illnesses, even though these illnesses have a quality of life worse than some advanced-stage cancers, Hanlon said.

“I can see why people were furious,” said JD Davids about the censorship “It’s an insult upon injury.” As the co-director of the advocacy group Long COVID Justice, Davids said that if the NIH wants to truly work and engage with patients, they need to work closely with people living with Long COVID and certainly not silence their lived experience.

“We need a government-wide response to Long COVID,” he said, describing the necessity for patients and complex chronic disease experts to be consulted on major decisions at the NIH and beyond. Tweeting that there is a treatment plan for a condition with no treatments or cures, Davids said, creates an illusion of a broader treatment plan for Long COVID, when there isn’t one. It confuses the public and creates doubt about people living with Long COVID. “It has huge unintended consequences,” Davids said.

Editor’s note: JD Davids has donated to the COVID-19 Data Dispatch. This had no influence on the article, as the author talked to him before the CDD decided to publish it.

Miles W. Griffis is an independent journalist based in Los Angeles, California. He’s written for High Country News, National Geographic, The New York Times, and many others.

If you are able to contribute a tip for this reporting, please Venmo @miles-griffis.