Four items from this week, in the real of COVID-19 and schools:

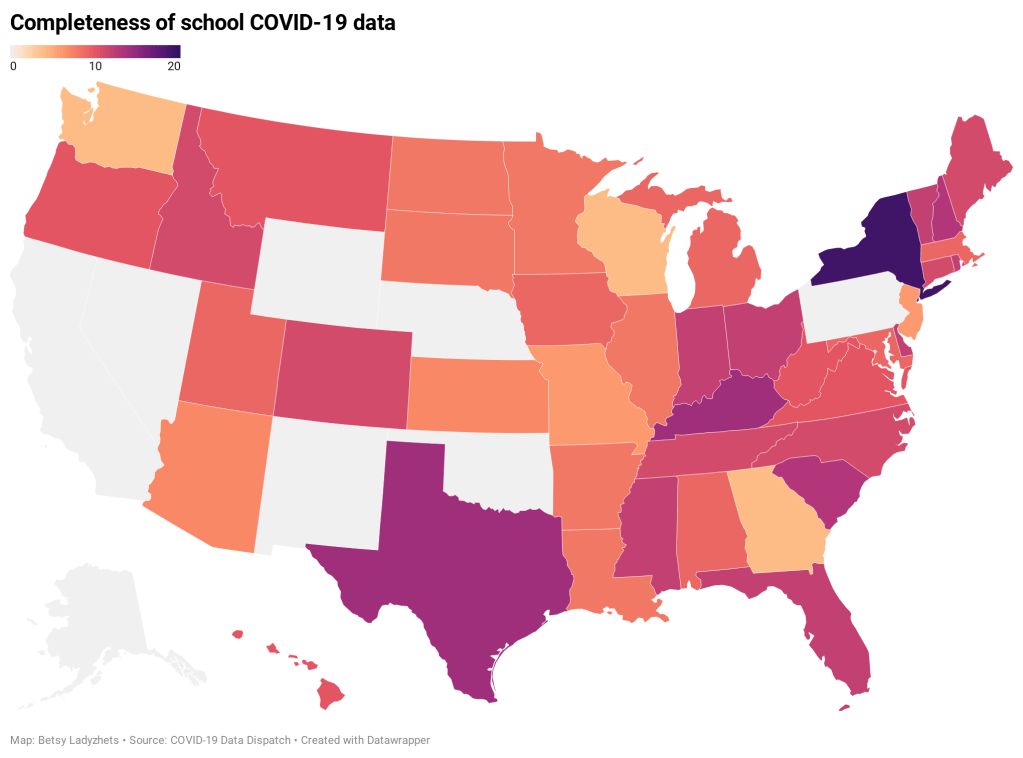

- New funding for school testing: As part of the Biden administration’s massive round of funding for school reopenings, $10 billion is specifically devoted to “COVID-19 screening testing for K-12 teachers, staff, and students in schools.” The Department of Education press release does not specify how schools will be required to report the results of these federally-funded tests, if at all. The data gap continues. (This page does list fund allocations for each state, though.)

- New paper (and database) on disparities due to school closures: This paper in Nature Human Behavior caught my attention this week. Two researchers from the Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy used anonymized cell phone data to compile a database tracking attendance changes at over 100,000 U.S. schools during the pandemic. Their results: school closures are more common in schools where more students have lower math scores, are students of color, have experienced homelessness, or are eligible for free/reduced-price lunches. The data are publicly available here.

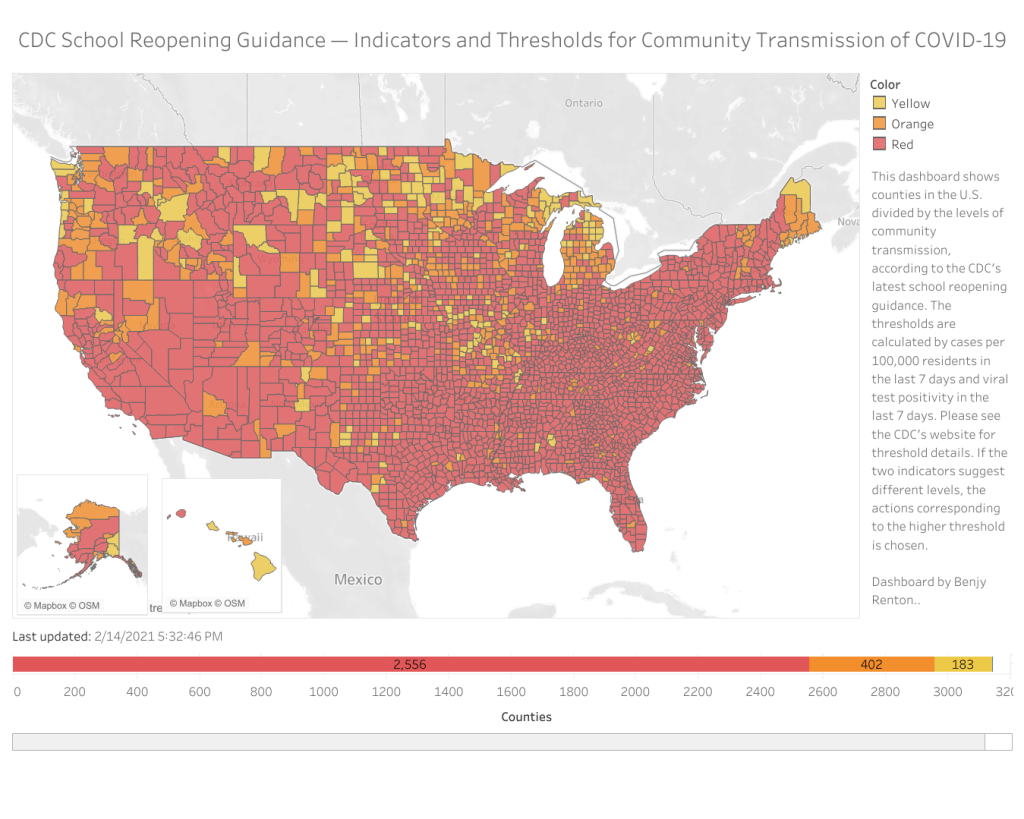

- New CDC guidance on schools: This past Friday, the CDC updated its guidance on operating schools during COVID-19 to half its previous physical distance requirement: instead of learning from six feet apart, students may now take it to only three feet. This change will allow for some schools to increase their capacity, bringing more students back into the classroom at once. The guidance is said to be based on updated research, though some critics have questioned why the scientific guidance appears to follow a political priority.

- New round of (Twitter) controversy: This week, The Atlantic published an article by economist Emily Oster with the headline, “Your Unvaccinated Kid Is Like a Vaccinated Grandma.” The piece quickly drew criticism from epidemiologists and other COVID-19 commentators, pointing out that the story has an ill-formed headline and pullquote, at best—and makes dangerously misleading comparisons, at worst. Here’s a thread that details major issues with the piece and another thread specifically on distortion of data. There is still a lot we don’t know about how COVID-19 impacts children, and the continued lack of K-12 schools data isn’t helping; as a result, I’m wary of supporting any broad conclusion like Oster’s, much as I may want to go visit my young cousins this summer.