By Philip Nelson

If you post in the COVID-19 data Twitter-sphere, you’re likely familiar with Philip Nelson, a computer science student at Winthrop University—and an expert in navigating and sharing data from the state of South Carolina. Philip posts regular South Carolina updates including the state’s case counts, hospitalizations, test positivity, and other major figures, and contributes to discussions about data analysis and accessibility.

I invited Philip to contribute a post this week after reading his Tweets about his ongoing challenges in accessing his state’s hospitalization data. Basically, after Philip publicized a backend data service that enabled users to see daily COVID-19 patient numbers by individual South Carolina hospital, the state restricted this service’s use—essentially making the data impossible for outside researchers to analyze.

To me, his story speaks to broader issues with state COVID-19 data, such as: agencies adding or removing data without explanation, a lack of clear data documentation, failure to advertise data sources to the public, and mismatches between state and federal data sources. These issues are, of course, tied to the systematic underfunding of state and local public health departments across the country, making them unequipped to respond to the pandemic.

South Carolina seems to be particularly arduous to deal with, however, as Philip describes below.

I’ve been collecting and visualizing South Carolina-related COVID-19 data since April 2020. I’m a computer science major at Winthrop University, so naturally I like to automate things, but collecting and aggregating data from constantly-changing data sources proved to be far more difficult than I anticipated.

At the beginning of the pandemic, I had barely opened Excel and had never used the Python library pandas, but I knew how to program and I was interested in tracking COVID-19 data. So, in early March 2020, I watched very closely as the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC) reported new cases.

During the early days of the pandemic, DHEC provided a single chart on their website with their numbers of negative and positive tests; I created a small spreadsheet tracking these cases. After a few days, DHEC transitioned to a dashboard that shared county level data.

On March 23, I noticed an issue with the new dashboard. Apparently, someone had misconfigured authentication on something in the backend. (When data sources are put behind authentication, anyone outside of the organization providing that source loses access.) The issue was quickly fixed and I carried on with my manual entry, but this was not the last time I’d have to think about authentication.

Initially, I manually entered the number of cases and deaths that DHEC reported. I thought I might be able to use the New York Times’ COVID-19 dataset, but after comparing it to the DHEC’s data, I decided that I’d have to continue my own manual entry.

South Carolina’s REST API

In August 2020, I encountered some other programmers on Twitter who had discovered a REST API on DHEC’s website. REST is a standard for APIs that make it easier for developers to use services on the web. In this case, I was able to make simple requests to the server and receive data as a response. After starting a database fundamentals course during the fall 2020 semester, I figured out how to query the service: I could use the data in the API to get cases and deaths for each county by day.

This API gave me the ability to automate all of my update processes. By further exploring the ArcGIS REST API website, I realized that DHEC had other data services available. In addition to county-level data, the agency also provided an API for cases by ZIP code. I used these data to create custom zip code level graphs upon request, and another person I encountered built a ZIP code map of cases.

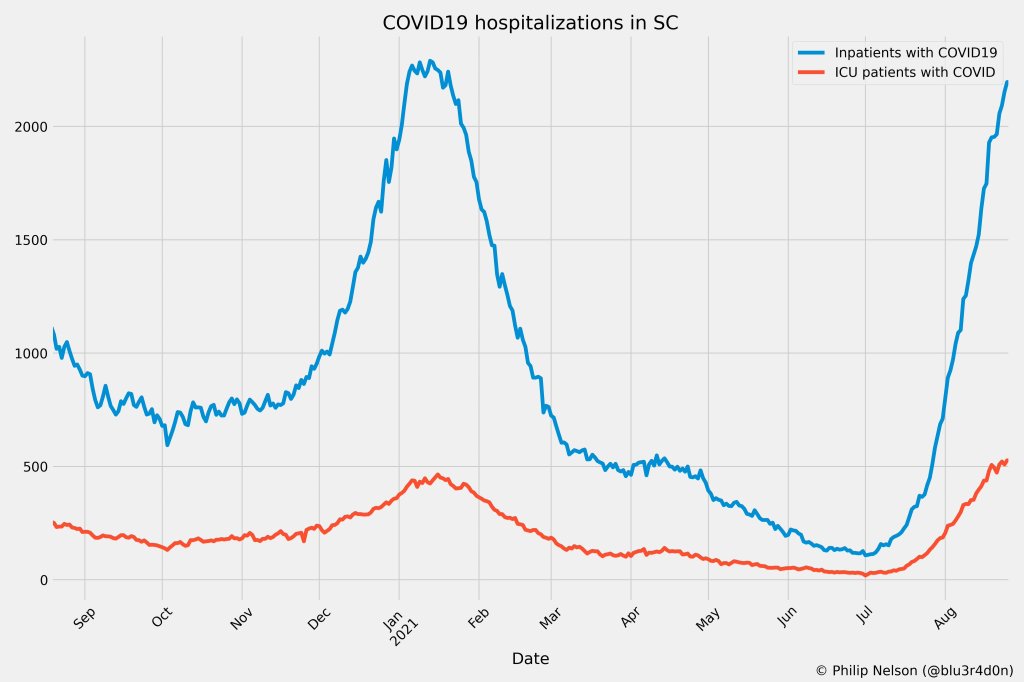

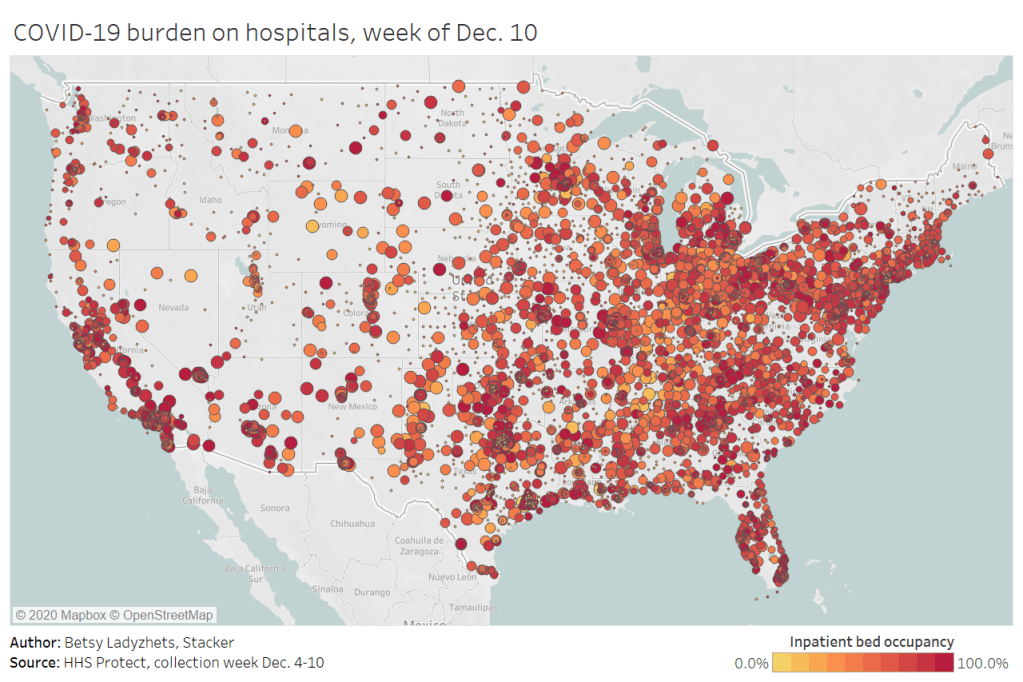

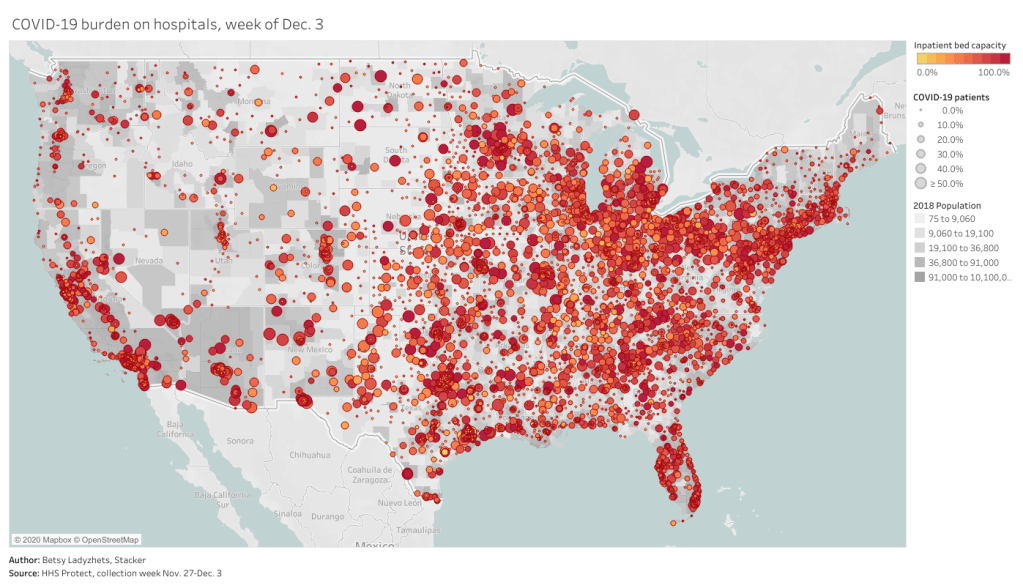

During August 2020, the CDC stopped reporting hospitalization data and the federal government shifted to using data collected by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and Teletracking. DHEC provided a geoservice for hospitalizations, based off of data provided to DHEC by Teletracking on behalf of the HHS. I did some exploration of the hospitalization REST API and found that the data in this API was facility-level (individual hospitals), updated daily. I aggregated the numbers in the API based on the report date in order to provide data for my hospitalization graph. At the time, I didn’t know that the federal government does not provide daily facility level data to the public.

In October 2020, DHEC put their ZIP code-level API behind authentication. I voiced my displeasure publicly. In late December 2020, DHEC put the API that contained county level cases and deaths behind authentication. At this point, I began to get frustrated with DHEC for putting things behind authentication without warning, but I kind-of gave up on getting the deaths data out of an API. Thankfully, DHEC still provided an API for confirmed cases, so I switched my scripts to scrape death data from PDFs provided by DHEC each day. I didn’t like using the PDFs because they did not capture deaths that were retroactively moved from one date to another, unlike the API.

I ran my daily updates until early June 2021, when DHEC changed their reporting format to a weekday-only schedule. I assumed that we’d seen the last wave of the pandemic and that, thanks to readily available vaccines, we had relegated the virus to a containable state. Unfortunately, that was not the case — and by mid-July, I had resumed my daily updates.

Hospitalization data issues

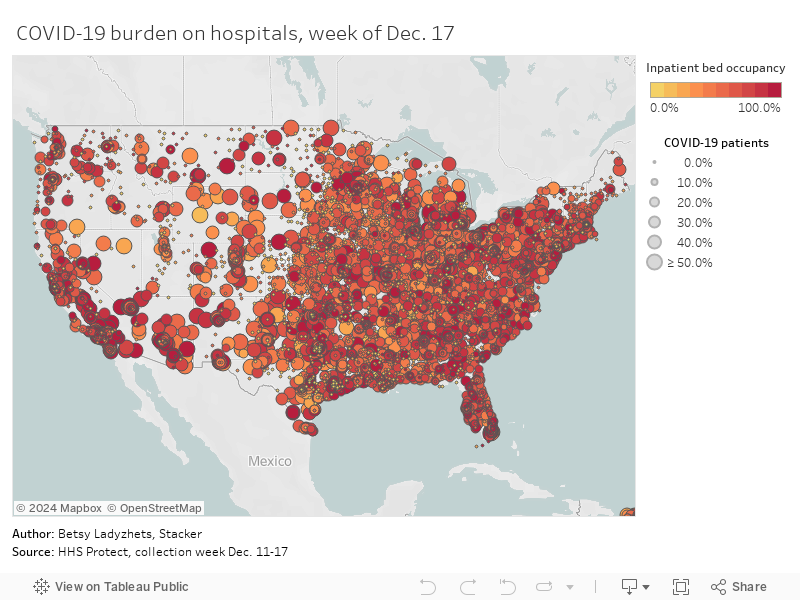

In August 2021, people in my Twitter circle became interested in pediatric data. I decided to return to exploring the hospitalization API because I knew it had pediatric-related attributes. It was during that exploration that I realized I had access to daily facility-level data that the federal government was not providing to the public; the federal government provides weekly facility-level data. My first reaction was to build a Tableau dashboard that let people look at the numbers of adults and pediatric patients with COVID19 at the facility level in South Carolina over time.

After posting that dashboard on Twitter, I kept hearing that people wanted a replacement for DHEC’s hospitalization dashboard which, at the time, only updated on Tuesdays. So, I made a similar dashboard that provided more information and allowed users to filter down to specific days and individual hospitals, then I tweeted it at DHEC. Admittedly, this probably wasn’t the smartest move.

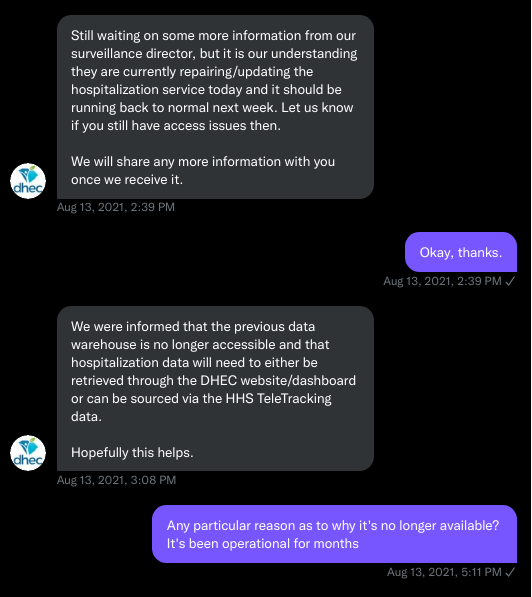

I kept exploring the hospitalization data and found that it contained COVID-19-related emergency department visits by day, another data point provided weekly by HHS. After plotting out the total number of visits each day and reading the criteria for this data point, I decided I needed to make another dashboard for this. A day after I posted the dashboard to Twitter, DHEC put the API I was using behind authentication, again I tweeted my frustration.

A little while later, DHEC messaged me on Twitter and told me that they were doing repairs to the API. I was later informed that the API was no longer accessible, and that I would have to use DHEC’s dashboard or HHS data. The agency’s dashboard does not allow data downloads, making it difficult for programmers to use it as a source for original analysis and visualization.

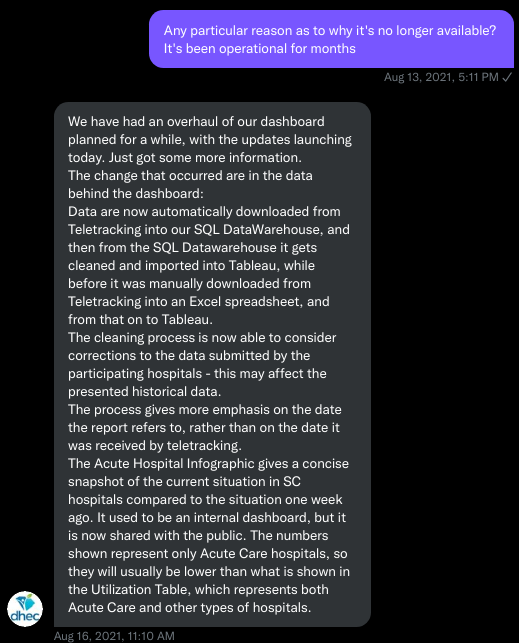

I asked for information on why the API was no longer operational; DHEC responded that they had overhauled their hospitalization dashboard, resulting in changes to how they ingest data from the federal government. This response did not make it clear why DHEC needed to put authentication on the daily facility-level hospitalization data.

Meanwhile, DHEC’s hospital utilization dashboard has started updating daily again. But after examining several days’ worth of data, I cannot figure out how the numbers on DHEC’s dashboard correlate to HHS data. I’ve tried matching columns from a range dates to the data displayed, but haven’t been able to find a date where the numbers are equal. DHEC says the data is sourced from HHS’ TeleTracking system on their dashboard, but it’s not immediately clear to me why the numbers do not match. I’ve asked DHEC for an explanation, but haven’t received a response.

Lack of transparency from DHEC

I’ve recently started to get familiar with the process of using FOIA requests. In the past week, I got answers on requests that I submitted to DHEC for probable cases by county per day. This data is publicly accessible (but not downloadable) via a Tableau dashboard, but there is over 500 days’ worth of data for 46 counties. The data DHEC gave to me through the FOI process are heavily suppressed and, in my opinion, not usable.

This has been quite a journey for me, especially in learning how to communicate and collect data. It’s also been a lesson in how government agencies don’t always do what we want them to with data. I’ve learned that sometimes government agencies don’t always explain (or publicize) the data they provide, and so the job of finding and understanding the data is left to the people who know how to pull the data from these sources.

It’s also been eye-opening to understand that sometimes, I’m not going to be able to get answers on why a state-level agency is publishing data that doesn’t match a federal agency’s data. Most of all, it’s been a reminder that we always need to press government-operated public health agencies to be as transparent as possible with public health data.