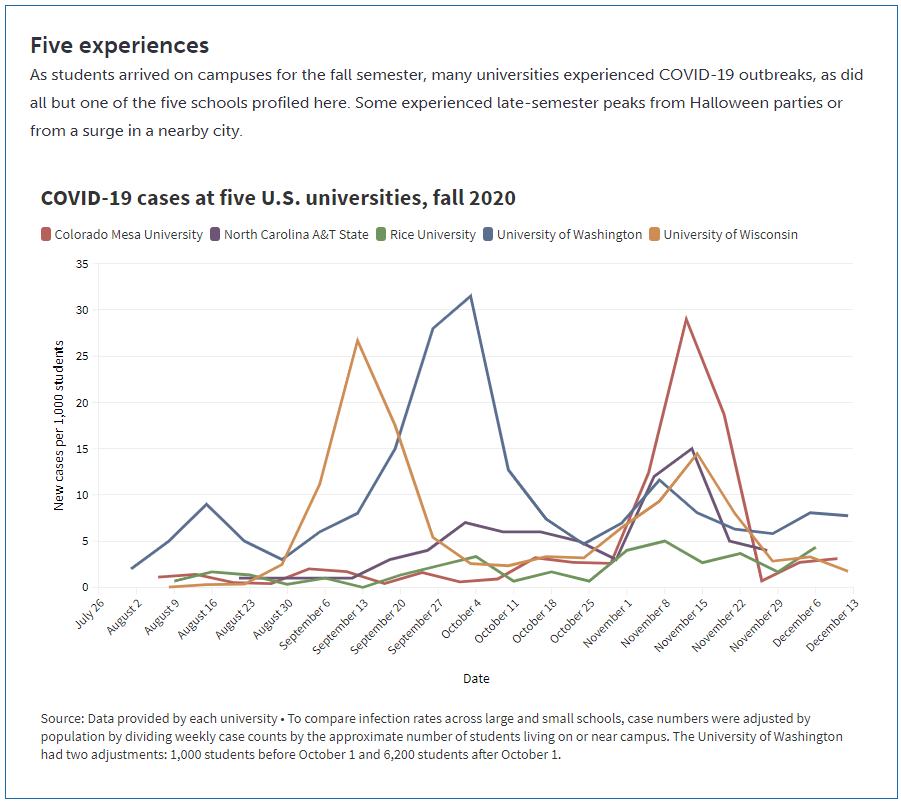

Despite outbreak risks, a lot of colleges and universities brought their students back to campus during the fall 2020 semester. Everyone from epidemiologists to the students themselves asked: What worked, and what didn’t? How do we even measure success, when every campus is unique and every option is complicated?

A lot of journalists have tried to answer these questions in the past few months. I took a crack at them in a feature for Science News, published this past Tuesday. My editor and I picked five universities, ranging from large state schools to small close-knit institutions. I graphed their cases and tests, attempting to determine both the drivers of campus outbreaks and how school leadership got them under control. And I spoke to administrators and students at each school who explained their campus’ approach to COVID-19 mitigation.

Obviously, I want you to read the full story. Any institution trying to handle COVID-19 can learn valuable lessons from these universities, especially from those that got their students involved in the COVID-19 protection efforts—like Rice University, which set up a student-run court to judge those who broke safety rules, or North Carolina Agricultural & Technical University, which let students go live on Instagram while they got tested.

But in the COVID-19 Data Dispatch this week, I wanted to share some bonus material. One of my favorite interviews that I did for this feature was with Dr. Pardis Sabeti, a computational geneticist at the Broad Institute of Harvard University and MIT. The Broad Institute helped over 100 colleges and universities set up COVID-19 testing and student symptom monitoring, most of them in New England. When I talked to Dr. Sabeti, though, she mostly spoke about Colorado Mesa University—a small school in Grand Junction, Colorado that saw it as a moral imperative to bring all of their students back to campus this fall.

Dr. Sabeti told me all about why the Broad Institute and Colorado Mesa University (or CMU) were a great match, able to try out novel COVID-19 control efforts that many other schools didn’t consider. She also gave me her perspective on what makes a successful pandemic semester—spoiler, she has a pretty high bar.

The interview below has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Betsy Ladyzhets: Tell me about how the Broad Institute started working on infectious disease management, and how that led to your current efforts with COVID-19.

Pardis Sabeti: I do a lot of work in infectious diseases, mostly in West Africa. In 2014, Harvard University set up an outbreak surveillance committee that helped the school through all of these things around Ebola. And then, it was sort-of in-place, we had this committee of folks across the institution that were working together on outbreaks.

Then, in 2016, we got re-empaneled when there was a mumps outbreak at Harvard that ended up spreading across Massachusetts. We learned that yes, universities are laboratories for infectious disease spread, and Massachusetts has 110 of them.

So, there was a lot going on there. We worked with the Mass. Department of Public Health and the higher ed consortium in Boston and we were really able to move things forward together, to cooperate, share data. We even found a transmission link between an outbreak—there was an outbreak in east Boston that happened in an unvaccinated community that was thought to be a separate outbreak, but then our genome sequencing data showed that it was firmly within the Harvard University cluster. And then additional case investigations showed that there were three members of that community that were Harvard affiliates, that were the likely links.

When we did the genome sequencing, it showed us this idea that traditional epidemiology is very accurate. Whatever links the public health teams had found, we confirmed with genome sequencing. But they missed most of the transmissions. There were a lot of transmission events that were very obviously tied to each other but that the public health teams didn’t catch.

So at that point, we really doubled down on this idea of genome sequencing and genomic epidemiology being really important for understanding outbreaks. But then also, we understood that we needed to be very fast about doing outbreaks [sic]. What the rest of the world figured out during COVID, we figured out because of mumps—that we needed apps to essentially allow people to start sharing information about their symptoms, so people can get quick diagnoses.

It was this funny thing where four people on my team all became infected while we were investigating the mumps outbreak with what looked like mumps. Each of them went to their own PCP [primary care provider], and their own PCP did a work-up, and you’re like—wait a second. Wouldn’t it be useful to know these four people are all in connection with each other? If one of them had a diagnosis, it would probably inform everyone else’s diagnosis.

We created what’s now called Scout. It’s an app that allows you to share with your contacts what’s going on if you have an infection, allows people to quickly figure out what their diagnosis might be and to alert people. We weren’t thinking about it necessarily for pandemic reporting. We were just thinking, wouldn’t it be something handy, that next time you get sick, you immediately know what you have and what to do about it. Particularly since viral and bacterial infections need entirely different courses of action from people. Like, could we help everybody get informed? And then we also built Lookout, which is a dashboard that collects all that information and shows public health teams and administrators what’s going on.

BL: Yeah, the CMU administrators I talked to talked about that [dashboard] a lot.

PS: Yeah, which is great. We joke that CMU has one of the most sophisticated public health systems. The school can see, at this exquisite level, what the cases are, where they’re located. It’s really allowing you to do those investigations that most people I’ve seen elsewhere are doing on the back of an envelope.

We [Broad] needed a place to work with that was going to be very collaborative and open. And so we were talking to a lot of different folks in different places, and everywhere there were different challenges of getting in the ground. And Colorado Mesa, to us, was this breath of fresh air. One, it was heartwarming to be working with this school in Colorado that has a large population of first-in-their-families-to-go-to-college students. And it was also empowering to hear the need that they had, the fact that they had to come back and they had to come back fully on campus because the students’ livelihoods and future success depended on it. And it was also heartwarming to see the way that the leadership was so engaged, so strong, so open, to anything.

And also, like, the wastewater testing is being done by faculty and students in the engineering department. The clinical sample collection is being led by Amy Bronson and the nursing team. That’s a lot of what you want to see happening on college campuses. To me, the way I pitched it is, what we were building was the Facebook app for outbreaks that also needed to start with a close-knit community where you could get a lot of adoption.

But also, this idea that colleges are both high risk but also exactly where innovation can happen. It’s where people are ready to explore and try things out.

I hadn’t seen that [mindset] at a lot of other schools. I saw this administrator, top-down, we’re gonna tell you how to behave and you’re gonna be in this room. A lot of schools got into a frame of like, we’re gonna manage these students, whereas CMU really was like, no, we’re going to partner with these brilliant students and figure this out together.

In my mind, I was always perplexed, where we kept describing this year as this kind-of less-than year, where we were just going to suffer through education. In my mind, it was a more-than year. People learn the best when the stakes are the highest. There’s no other time we’re gonna teach kids about public health, infectious disease, genomics, and epidemiology than now. So we should shift what we’re trying to do. It shouldn’t be like, let’s get the Chaucer done while an outbreak is killing people in our community. We should’ve shifted our attention and all learned math, and stats, and clinical medicine, and public health, and biology around what’s going on.

And that’s what CMU is doing. They’re hosting classes that are around outbreak response. The coaching teams and the sports teams are the ones doing contact tracing. It’s interesting, because it’s, in a way, it’s a school that doesn’t have all the resources where the ingenuity is going to happen. They can’t just call an outside consultant to do these things for them, they had to rely on themselves and the students.

Did they show you the videos that they made?

BL: I watched that “CMU is Back” one, which is great.

PS: Yeah. They made many of them. They have a new song—I have to make a video later this afternoon for it.

The fascinating thing is, right, even the art students got in on it and started doing public health messaging. I say, and it’s true—they already had me at the team. I just thought the team was so delightful and inspiring, but they sealed the deal with the video.

What communities do you know that would make a video together? Most offices, they hate each other, everyone’s resentful and no one’s gonna make a video. In a lot of the schools that I know, there’s taglines that they hate the administration. There’s a fight between the administration and the students. Where here, it’s like, the administrators and the students got together and made a music video. They told me that they have a very close-knit culture and a trust in each other, that would make things go forward.

And I’m sorry, I know this is very much my pitch for CMU, but I just love talking about this place. Here’s this thing where—did they show you the simulation that happened over Halloween weekend? Did they show you that data?

BL: I think so, yeah.

PS: It was the real-time where you’re seeing everybody clustering?

BL: Oh yeah, yeah.

PS: Yeah. What is fascinating about that whole scenario is that you had 358 students, voluntarily without any real advertisement from us, download an app that tracks all of their movements over Bluetooth, over Halloween weekend. And then proceeded to go out and do their thing. So here’s that kind-of interaction, and you’re seeing, minute-by-minute, the kind-of high resolution data that we’re getting on how students are interacting with each other. What clusters they’re forming, what times of day we need to watch out for for interactions. It’s pretty bananas.

These students have an enormous number of contacts. This is the fear that you have with college students. Someone might look at [these data] and say, it’s terrible. But in other ways, it’s like, these kids trusted you enough to download an app, get themselves tracked, and go on and basically engage in behavior that they could get themselves thrown out. That’s trust in the leadership. That is what we need to be able to stop outbreaks.

And then, the last piece I’ll say before I go off of my CMU storyline is… I’ve been trying in Massachusetts, for a long time, to get people to understand that you’re gonna spend millions. Each of these colleges are spending millions and millions of dollars on diagnostic testing on a daily basis or a weekly basis. That’s an incredible amount of tests that are being used with no hypothesis. Meanwhile, the surrounding communities are talking about seven days ‘til getting a test result, and standing in line for four hours for a test.

That’s dangerous. I kept trying to convince a lot of the colleges that testing yourself in the middle of a shortage of tests looks selfish and is ineffective. Ultimately, the way that COVID spreads, one person can come into a room and infect 50 people. And so, the metaphor I use is, it’s like being in a drought with a fire alarm shortage, and putting all the fire alarms in your own house. You’ll be exquisitely good at detecting a fire when it hits your house, but at that point, it’s burning to the ground. What you should do is, you should get [the fire alarms], and you should put them in all your neighbors’ homes. For a wide stretch.

Ultimately, what colleges should do is to support their communities’ testing, by reaching out and saying, okay, every faculty and staff and student, tell us who your contacts are, and have them tell us who their contacts are, and we will prioritize testing for those individuals. We’ll get them tested. That’s how the colleges should have interacted.

And that really fell on deaf ears in general, there’s a variety of reasons for that. But Colorado Mesa doubled down. We [Broad] tried all these different models, like use 100% of your tests on yourself, use 100% of your tests on other people, or use 25%, 50%, 75%, those different groupings. And we found that the most effective way of stopping an outbreak is if you use 75% of your tests outside of the school. You keep 25% for yourself, but 75% should be used outside the school. That’s how you stop outbreaks on campus.

We’re writing up that work right now, but even when we showed Colorado Mesa the preliminary data, they were like—that’s now their new model. It’s essentially what they’ve done. They’re putting the majority of their tests [in Grand Junction, the city around the school]. And to me, that’s going to be the really remarkable thing to watch going forward. We’ve created the apps, and the dashboards, and the systems to be able to do this well, but now we really want to reach out to our surrounding community and see where we can go here.

BL: I know they mentioned to me that they were starting to help the other schools—like, the elementary and middle and high schools in Grand Junction get tested as well.

PS: Yeah. Our foray into community testing was there. Basically, when the school stopped and they had this break over the holidays, they started pushing this community testing… It’s all about trust, right? They got the trust of their students, and now they’re getting the trust of the community. They’re saying, okay, we’re here to help you, how do we work through this together. That’s the idea behind it.

So that’s all of my CMU backstory. But it also just generally tells you about the way I think things need to happen. Colleges are both a laboratory for infectious disease spread and also a great laboratory in which to try new technologies out, but it really has to involve community engagement, empowering of all the actors in the system, and trust-building. It does have to involve bringing the students on board on the mission, not just coming top-down and telling them how to do things, and reaching out to the communities and doing testing for your communities.

It both makes you look more selfless because you’re a college helping your community. That’s always a great way, when you’re going to throw a party in the middle of the night, for them to be happy that you’re there. This[fall 2020] was the opportunity for all colleges to get buy-in from their communities, to show why they’re there and why they’re useful, and that’s another thing where it’s like, why are we not doing that? We have that opportunity.

BL: That’s definitely something that I saw in part at some of the other schools [in my story], but not to the same degree as what Colorado Mesa was doing. I think you answered a lot of my questions already, because I was going to ask you, like, what makes colleges a good place to try out mitigation methods.

But one more question is, do you have specific parameters that you would think about when you look at, say, cases and testing numbers, of what you would consider a successful fall semester for a campus?

PS: The thing is, most schools had very unsuccessful semesters…. For me, success would be… The bar for me for success is really high. To justify coming back when so many people can’t… It would be, not having an outbreak on campus, or not seeding an outbreak in the community. Which could happen—you could not have an outbreak on campus but could have seeded one in the community, if you caught it and you were able to quarantine your people but you already spread it there and the whole thing went on fire. Essentially if your surrounding community has lower case rates.

I always talk about, when you do something that’s counter to what you should be doing, success is going far and beyond. For me, when I have my students go into someone else’s lab, I’m like, you need to leave that lab better than when you found it. If you’re a guest in someone’s home, if you are treading in a place you shouldn’t tread, your level of success is leaving the college and the community better than when you found it. And having the students learn new skills, be engaged, and feel excited about the future.

The fact, again, that CMU has their new song— which they just sent me, and it’s a little silly ‘cause it has all these excerpts of me talking—is, “The Future is Now.” And that, to me—even though, by the metrics of what I was just talking about, they weren’t successful. They had an outbreak on campus, it might have spread to the community. But they made a big headway, they learned a lot, the students engaged a ton, and they collectively were making the community around them better. That to me is—I think they had a successful semester in that the students were engaged and they learned, and they attempted to support the community around them. And from that will learn to be even better and stronger.

BL: Is there anything in particular that you are expecting to be different this spring, learning from CMU and from the other schools you’ve worked with via the Broad Institute?

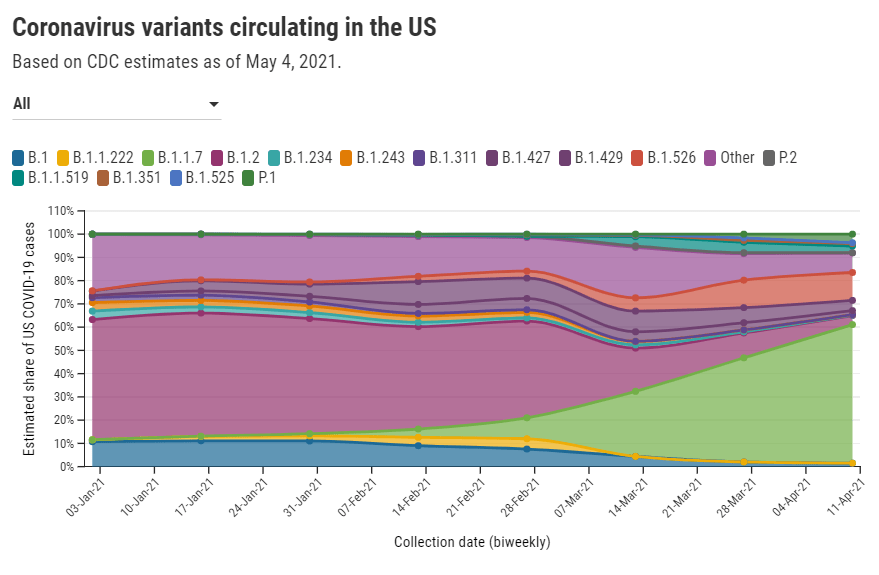

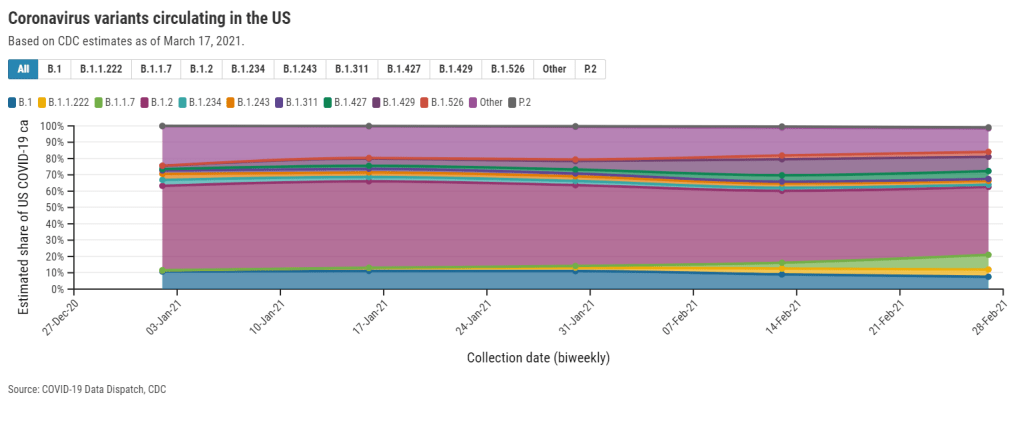

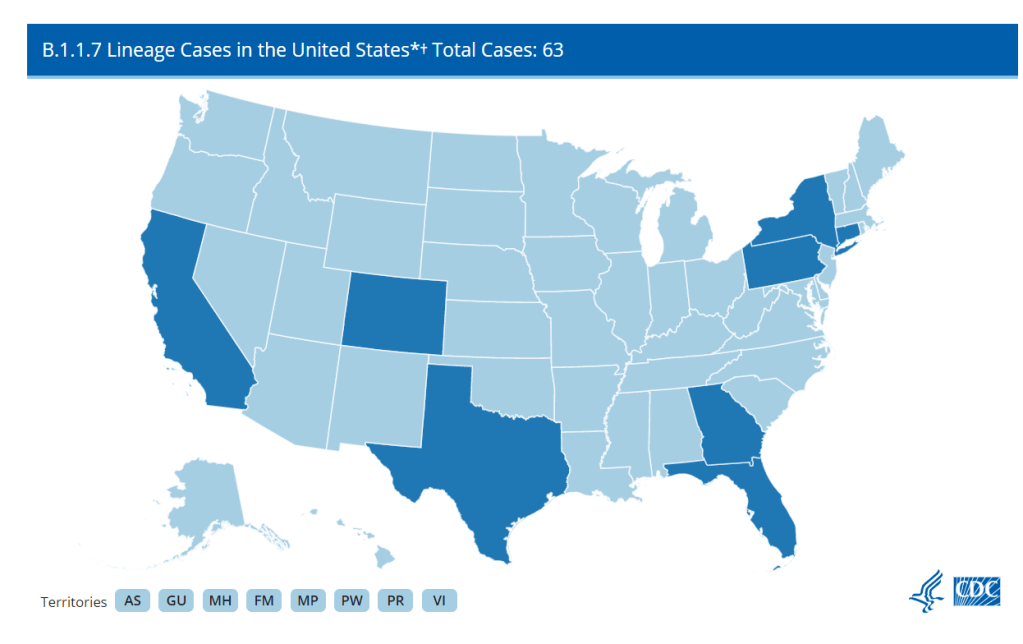

PS: This spring is going to be very… it’s going to be hard to know how it will go. You’re gonna get vaccines coming in, that’s gonna make things better, but you have case numbers that are really high, variants that are more infectious, that are gonna make things worse. And a lot of civil unrest and tensions and all of that.

It’s one of those things where we really have to double down on our civic engagement, I think that’s going to be really important. And on our public health view of what’s going on.