This past Monday, the CDC put out a major data release: mortality data for 2020 and 2021, encompassing the pandemic’s impact on deaths from all causes in the U.S.

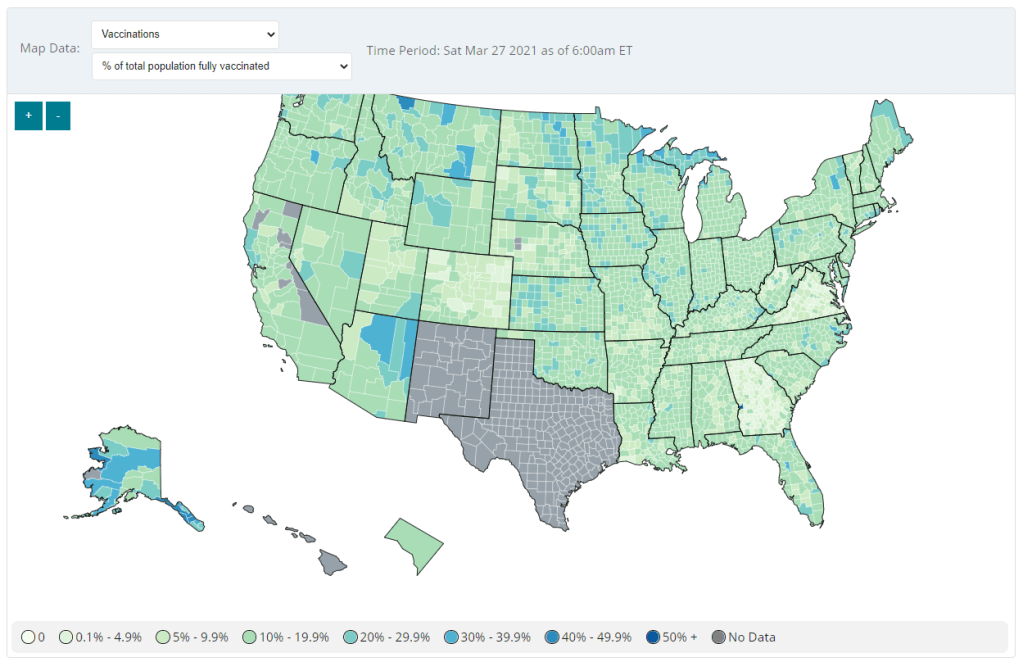

The new data allow researchers and reporters to investigate excess deaths, a measure of the pandemic’s true toll—comparing the number of deaths that occurred in a particular region, during a particular year, to deaths that would’ve been expected had COVID-19 not occurred. At the same time, the new data allow for investigations into COVID-19 disparities and increased deaths of non-COVID causes during the pandemic.

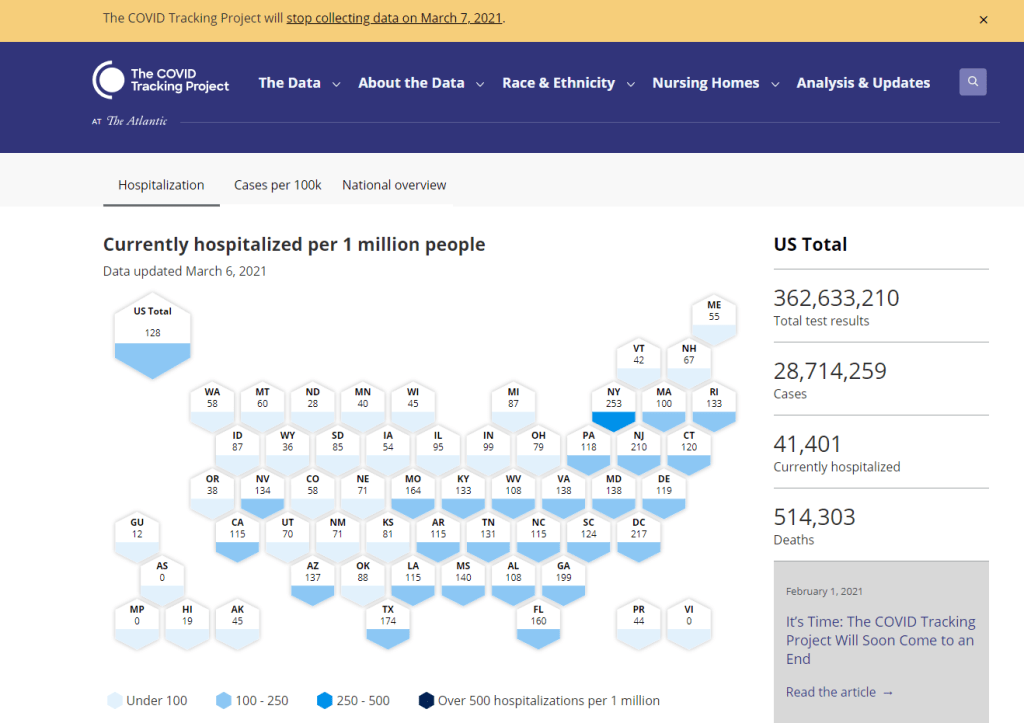

To give you a sense of the scale here: As of Saturday, the U.S. has reported almost 800,000 COVID-19 deaths. But experts say the true COVID-19 death toll may be 20% higher, meaning that one million Americans have died from the virus. And that’s not counting deaths tied to isolation, drug overdoses, missed healthcare, and other pandemic-related causes.

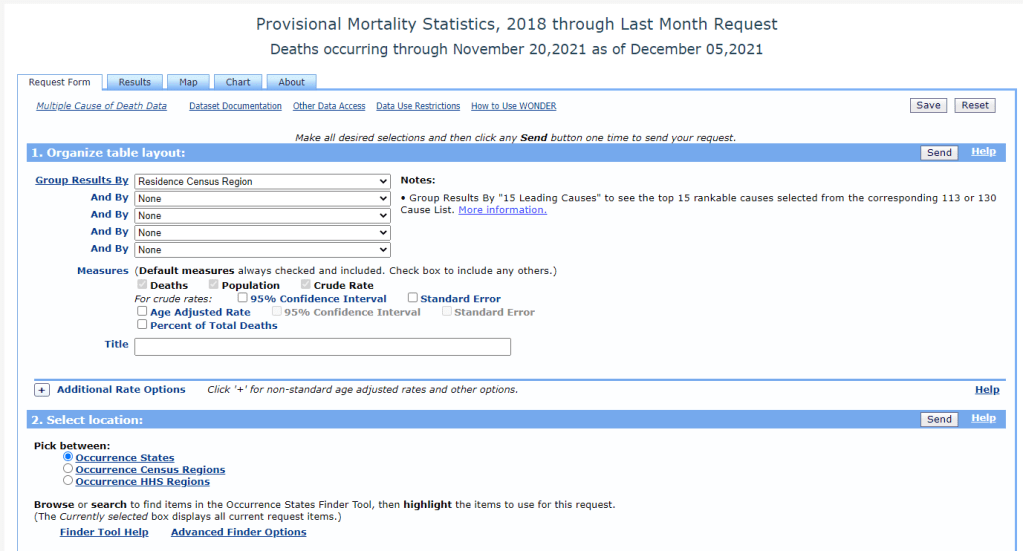

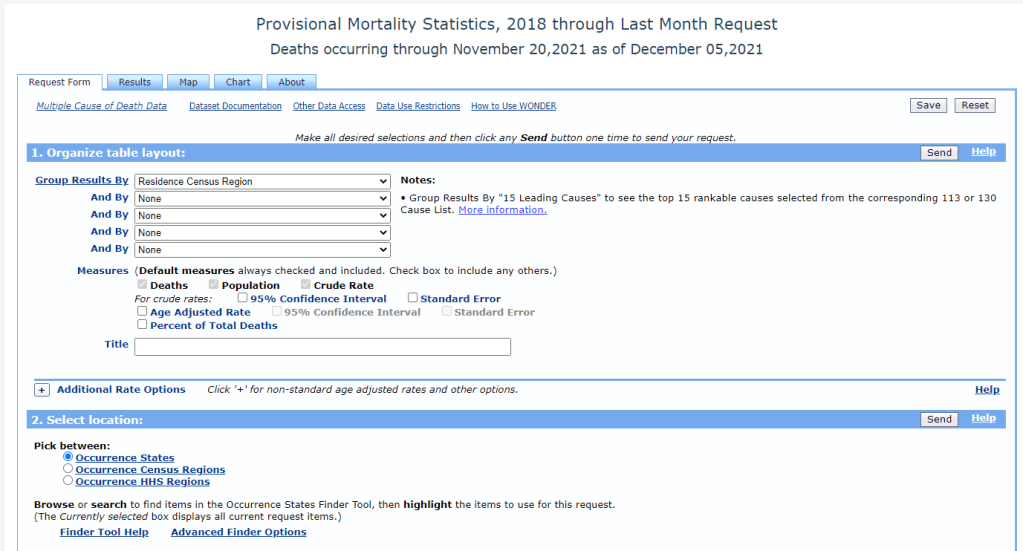

The CDC’s new data release is unique because, in a typical year, the CDC reports mortality data with a huge lag. Deaths from 2019 were reported in early 2021, for example. But now, the CDC has adapted its reporting system to provide the same level of detail that we’d typically get with that huge lag—now with a lag of just a few weeks. The CDC has also improved its WONDER query system, allowing researchers to search the data with more detail than before.

“I would describe this new release as more real-time surveillance at more specific detail than any journalists, or epidemiologists, or any other kind of researcher even knows what to do with,” said Dillon Bergin, an investigative reporter and my colleague at the Documenting COVID-19 project, at the Brown Institute for Media Innovation and MuckRock.

Along with Dillon and other Documenting COVID-19 reporters, I worked on a story explaining why these CDC data are such a big deal—along with what we’re seeing in the numbers so far. The story was published this week at USA Today and at MuckRock. Our team also compiled a data repository with state-level information from the new CDC release, combined with death data from 2019 and excess deaths.

If you’re a reporter who’d like to learn more about the new CDC data, you can sign up for a webinar with the Documenting COVID-19 team—taking place next Wednesday, December 15, at 12 PM Eastern time. It’s free and will go for about an hour, with lots of time for questions. Sign up here!

Editor’s note, December 27: This webinar was recorded; you can watch the recording here.

Also, as our initial story is part of a larger investigation (in collaboration with USA Today), the team has put together a callout form for people to share their stories around COVID-19 deaths in their communities. If you have a story to share, you can fill out the form here.

To provide some more information on why this new CDC release is so exciting—and what you can do with the data—I asked Dillon a few questions about it. As the lead reporter on our team’s excess deaths investigation, he’s spent more time with these data than anyone else. This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Betsy Ladyzhets: How would you summarize this new release? What is it?

Dillon Bergin: I would describe this new release as more real-time surveillance at more specific detail than any journalists, or epidemiologists, or any other kind of researcher even knows what to do with. It’s unfathomably detailed, and the fact that we’re going to be able to see updates in almost real time is really critical at this stage of the pandemic, or at any stage in a public health crisis. I think it’s a huge, huge step forward.

BL: Specifically in the realm of COVID deaths, but also, all deaths during the pandemic.

DB: Exactly, yes. In the realm of COVID deaths, we do know that there is a large gap between the total amount of excess deaths and the excess deaths that COVID accounts for. So it’s interesting from that angle, understanding what COVID might have been misclassified. But the data can also be used for a broad range of other types of deaths that have happened during the pandemic or possibly increased during the pandemic.

BL: So why are researchers excited about this data release?

DB: Previously, for something to go up on the WONDER website, or to become WONDER data, has to be finalized in the year after. So, data from 2020 would just be finalized now. Typically, we might not see that data until, probably, early in the new year [2022].

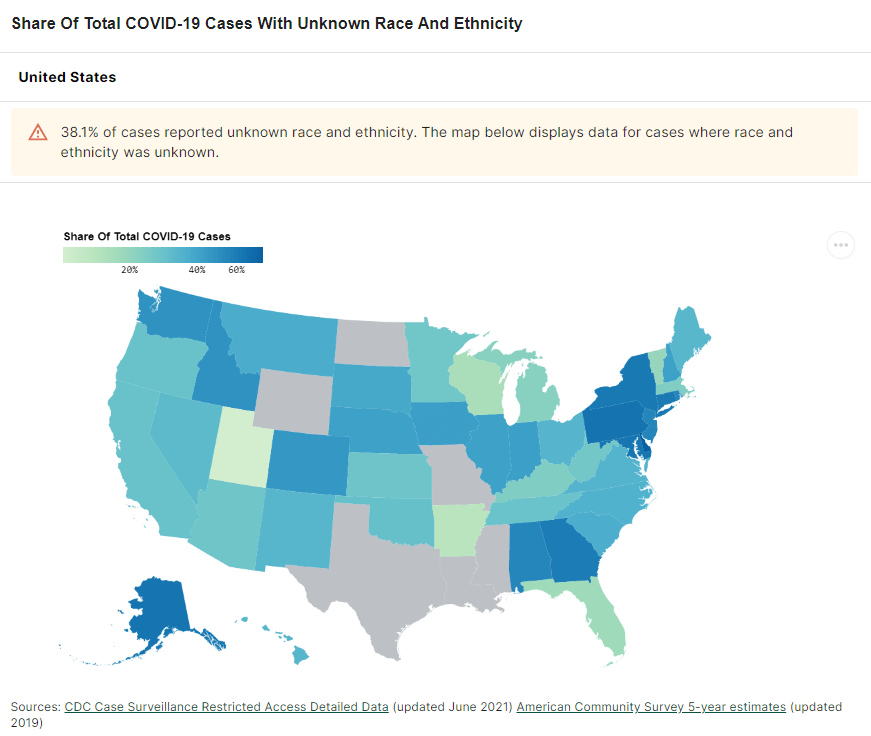

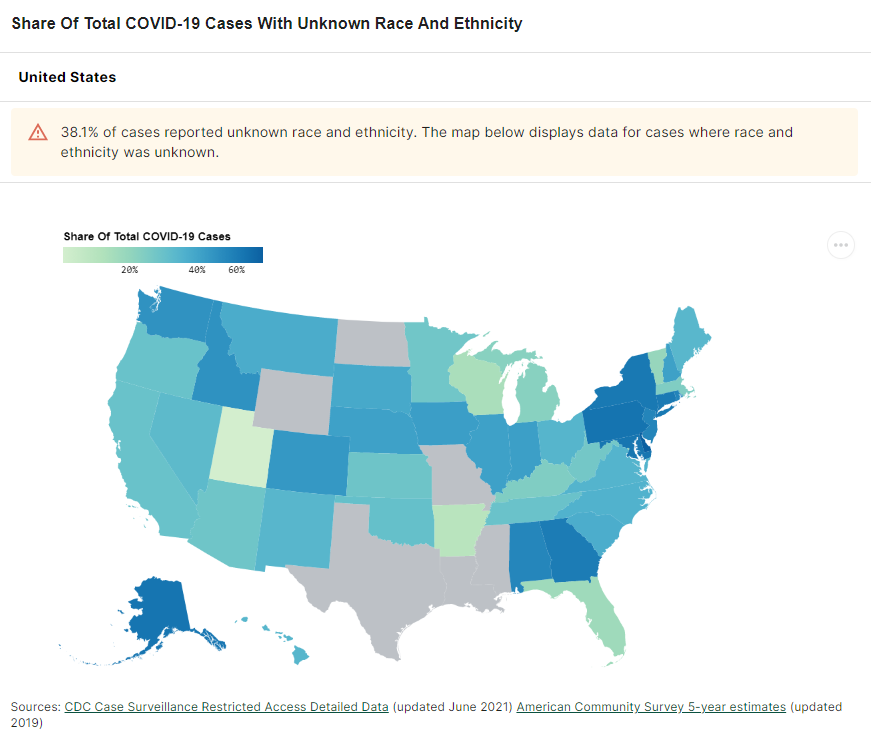

But with the new tool, we’re getting that 2020 and 2021 WONDER data now. And the CDC does a great job of providing a lot of granular details about causes of death, and racial demographics… Those are things that general CDC [mortality] data gives you, but the WONDER data is even more detailed. So, the fact that researchers don’t have to wait anymore for that data to be finalized, that the CDC is providing provisional data at such a detailed level—that’s what researchers are excited about.

BL: It’s the provisional data that’s being released, like, a year earlier than you would normally expect it to be published, right?

DB: Yeah, a year earlier than you would expect it to be published. Which means it’s almost real-time, because it has, I think, a three- or four- week lag. This data is real-time public health surveillance at a highly granular level—which is what people have been asking for. It’s what epidemiologists have been asking for, researchers, advocates of all kinds, journalists, lots of people have been saying, “We need this type of surveillance.”

BL: When you say a three- or four-week lag—the CDC is going to update it every couple of weeks, right?

DB: Yes, that’s correct.

BL: Do you have a sense of what the update schedule is going to be, or is the CDC not sure yet?

DB: I’m not sure. I know it was a big haul for them to just get this out, I’m not sure what the next update will be…

BL: Yeah, well, I’m sure we [Documenting COVID-19] will keep an eye on it. And we’ll tell everybody when it updates. (Editor’s note: As of December 12, it has already been updated! Data now go through November 20, 2021.) So, what are some of the things that you’ve seen in the data from the preliminary analysis that you’ve done so far?

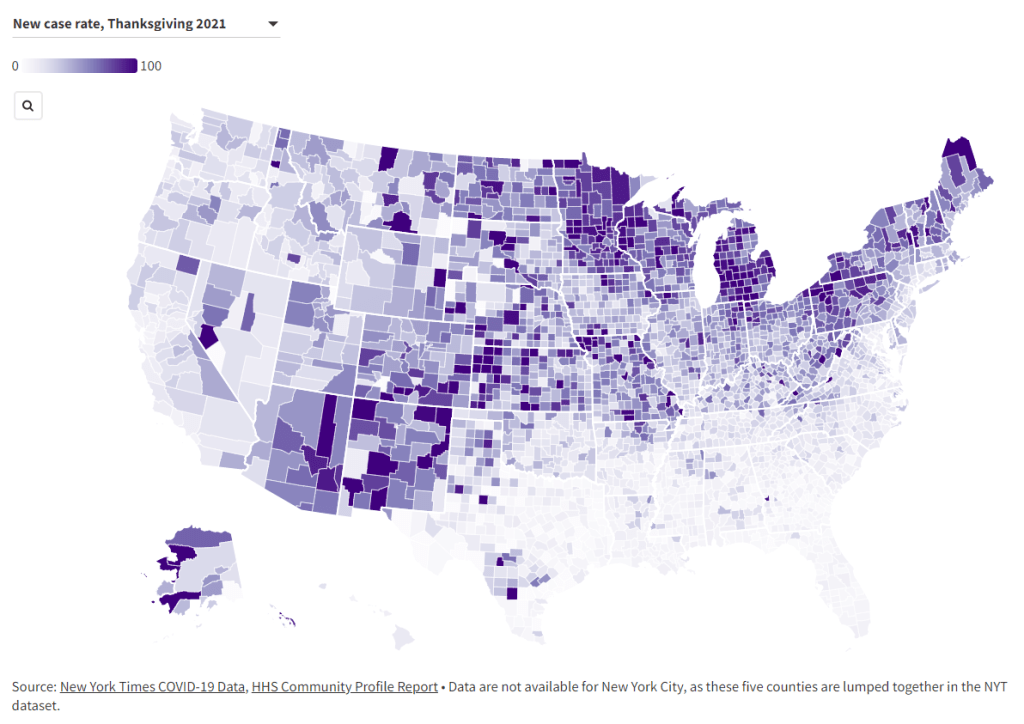

DB: One of the specific things that I’ve seen, that’s been really important for the work that I’m doing right now, is increases of different types of deaths at home. When people die, they don’t always die in a hospital—they could die in an outpatient clinic, or in an ER, or they could come to the hospital dead on arrival, they could die in hospice, or a nursing home, or at home.

And one of the awesome things about the CDC data is that you can see, actually, where people have died, and what specific causes of death that those people had when they died. Or, to be precise, you can’t see specific people—but you can see, say, 50 people died of heart attacks in a specific county at home. You would be able to see [in the data] that those people not only died of a heart attack, but they died at home.

The takeaway for me has been that respiratory and cardiovascular deaths have increased at home in specific states and counties. Louisiana is one example: it looks like Louisiana has the highest increase of deaths at home from [the CDC designation] “other forms of heart disease,” of any state, at like a 60% increase from previous years. So then we have to ask ourselves, what could lead to that increase? Are people really dying more of heart disease at home, by that much higher of a rate? Or is something else going on here?

BL: If you were talking to local reporters about this, what would they recommend that they do with the data?

DB: I would recommend that they take a look at the most recent data, the data from 2020 and 2021, for their area. And also pull some previous years, probably five years [of data], and start looking at causes of death, ages of the people who died, racial and demographic makeup, and place of death. I think different combinations of those data will start to provide some interesting avenues that can lead you to do actual human reporting—asking, what was happening? And why was that happening at this scale?

The new WONDER data, you can kind-of stretch it and bend it in so many different ways, it can be a little bit intimidating at first. So maybe, it would also be useful to start with a more specific question. If you’re wondering about, let’s say, certain types of deaths in a very specific county. Say you’re wondering if that’s from unintentional drug overdoses, or deaths from respiratory diseases in your county. Then you can start looking at the more granular level of details within those types of deaths—whether it’s racial and demographic makeup, or whether or not the body was autopsied. You can even see the day of the week [that people died]. There’s a lot of different places you can zoom in.

My overall advice would be: Start with a general question and then explore, then reform that question and explore, then reform that question. The data is both so extensive and so granular that you can get lost in it very quickly.

BL: You mentioned that it’s very intimidating, which I would second. The first time I looked at the WONDER data, I was like, “What is going on here?” So, what would be your recommendations for working with that data tool? Or any major caveats that you think people should know before they dive into this?

DB: That’s a great question, because with WONDER, you have to use their querying tool through their website. You can’t really easily and quickly export things or work with an API, though you can export data once you do a query.

My first caveat would be, keep in mind the suppression of any values under 10. So, that means you can zoom in on certain things, but then you may also have to zoom out. For example, if you wanted to know the leading causes of death for someone, when a body is dead on arrival—if you do that search at a state level, you’ll probably be able to see the first five or so causes before you reach causes that have only happened between one and 10 times, and then that value is oppressed and you can’t see the information. But if you were to do the same search on a national level, you would have a lot more causes for those types of deaths.

So, I would keep in mind the suppression, when zooming in and out. And also keep in mind, if, say, you’re looking at “dead on arrival” deaths for every county in a specific state, so many causes of death for those [county-level searches] will be suppressed, that your totals from the counties would not match the actual totals [at the state level]. Because you may not be aware that the CDC is not showing you the values that were suppressed if you didn’t click a specific button—or if you’re quickly adding things.

BL: Another thing that [our team ran into] is occurrence versus residence—that’s something people need to know about. “Residence” means sorting by where people lived, “occurrence” means sorting by where they died. Those don’t always match up.

DB: Yes, I would say residence versus occurrence is very important to keep in mind, especially because, when you’re redoing a search and scrolling very fast, you can accidentally fill out a state for occurrence instead of residence. Which actually did happen to me, and then I was confused by my own numbers. Then I noticed that there were a bunch of states coming up that I hadn’t meant to search for, because I, like, filtered by residence and then searched by occurrence.

So yeah, keeping in mind the difference between residence and occurrence is definitely important. Though if you go back in the historical data [before 2018], it’s just residence—just a single state for each death.

Also, just clear some extra time to get used to working with the WONDER interface. Because, unlike the CDC data updates that are just on the data.cdc.gov website, that you can just quickly download and open up in your technical took of choice—for WONDER, you do have to use the WONDER query site, and it can be difficult to get used to searching and importing.

BL: I will say one more thing, while we’re on this topic, that I’ve been doing and that might be helpful for other people: make sure that, if you export data from WONDER, that you always save that notes section it gives you at the bottom [of the exported file]. Because that will tell you exactly what you searched for. So, if you want to replicate something later, you can just go back and look at the notes. I feel like my instinct, often, when I’m looking at a dataset, is to delete all the notes and anything I don’t need—so I have to remind myself, like, “No, you should keep this.”

DB: That’s actually a really good tip, because I do that… I import the data [to my computer] and then I delete all the notes. That’s a great point.

BL: Also, what recommendations do you have if people are looking for, like, experts to interview about these data? Say a local reporter wants to search for experts in their area, what should they do?

DB: I can speak about that, because that’s been really useful for me in my reporting. Once you have this data, or once you’ve researched excess deaths in your area, you should talk with an epidemiologist or a social epidemiologist—someone who would know your state, or maybe even your more local area—about the broader mortality trends in your community. That will really give you a deep understanding of, what were the reasons that people were dying before the pandemic? And what has this expert thought about during the pandemic? And what have they heard, or read, or researched about why deaths are increasing? For example, I talked to two epidemiologists in Mississippi while working on our investigation, and they really helped me understand what I was looking at and looking for.

BL: Awesome. And then, my last, kind-of big picture question is, why does this matter for people who aren’t epidemiologists or COVID reporters?

DB: That is also a good question. I think the thing that I have been thinking about over and over again—and it’s something that an epidemiologist told me—which is that, if we understand how people die, then we might know what’s making them sick. And if we know what’s making them sick, then we have a shot at stopping that from happening.

This data is a very important step in that process, which is learning, in real-time, why people are dying. If we know that, we know what’s making them sick, whether it’s unintentional drug overdoses, or an increase of deaths because of lung cancer or heart disease. Any of those things are important to know, especially in a public health crisis like the one we’re in right now.

BL: I know we’ve talked before about this sort-of cycle of, what happens when COVID deaths are maybe undercounted in a certain community, and then that contributes to people maybe being less aware of COVID in their community. And then [that lack of awareness] contributes back to the same process.

DB: Yeah, exactly. I think that’s an important thing as well. Throughout this process—reporting on this topic, and working with this data, and thinking more about death certificates and the information on them—I’ve been increasingly… Not evangelized, exactly, but I’ve seen the light on the importance of that final piece of information of people’s lives. And what it means not only to their families and to the local area and communities, but also what it means when we start pulling that data up to larger and larger groups, and trying to understand: what does this person’s death mean at the level of the county, or the state, or in their racial demographic, or in their age demographic, or by gender?

All of this is critically important. And it sounds kind-of corny, but in a way, [the death certificate] is like, one really last piece of information that you leave behind for humans after you.