This week, the FDA and CDC authorized new booster shots from both Pfizer and Moderna that are tweaked to specifically target Omicron BA.4 and BA.5. The vaccines will start becoming available at pharmacies and doctors’ offices across the country in the coming days.

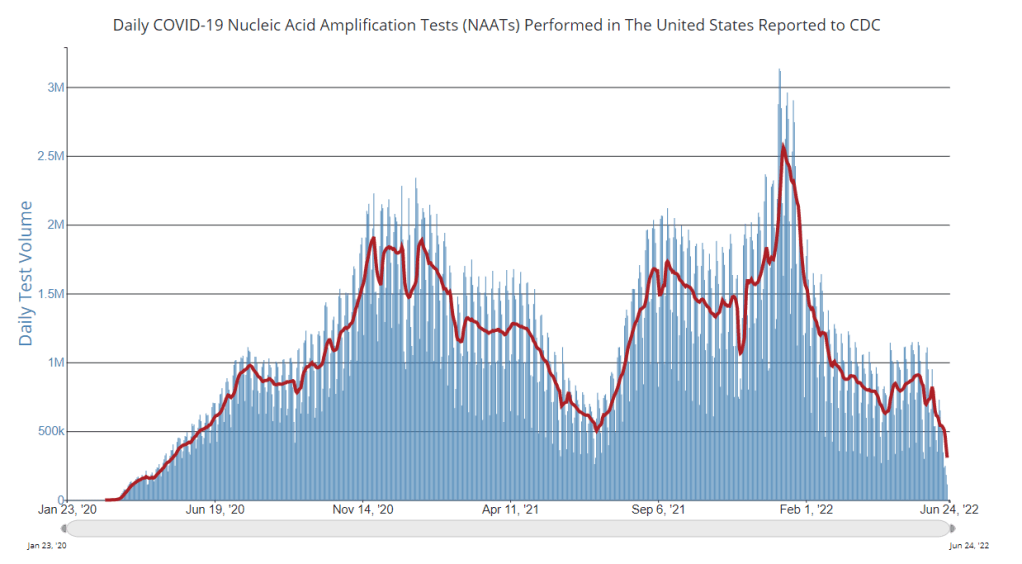

Much of the media coverage of these new boosters has focused on the fact that they’re the first COVID-19 vaccines derived from a newer variant, as opposed to the original Wuhan strain. BA.5 and BA.4.6, a sublineage of BA.4, are causing almost all COVID-19 cases in the country right now; some experts hope that a booster campaign targeted to these versions of the coronavirus will lead to actual decreases in transmission, not just severe disease.

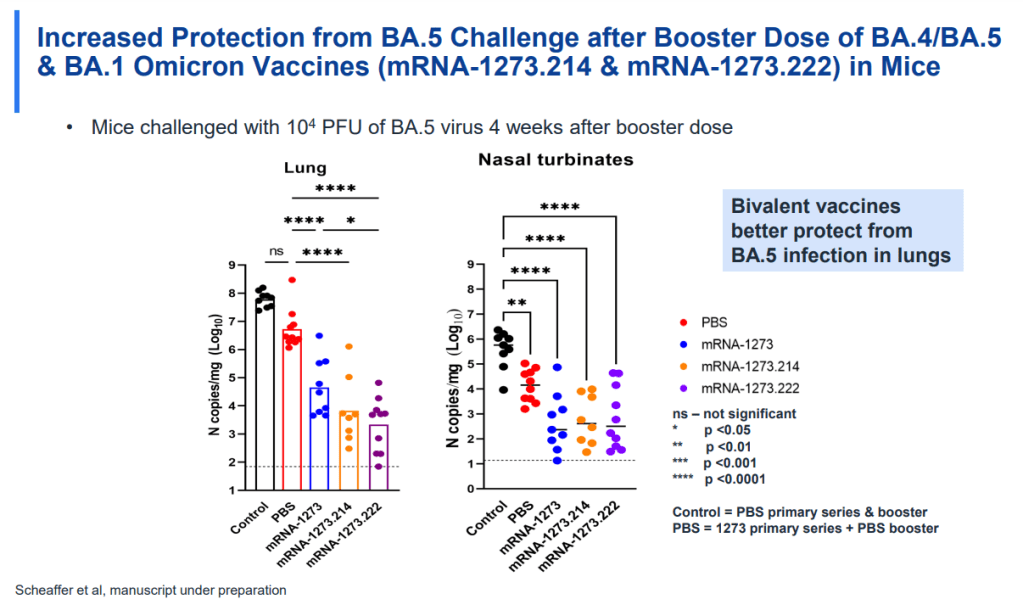

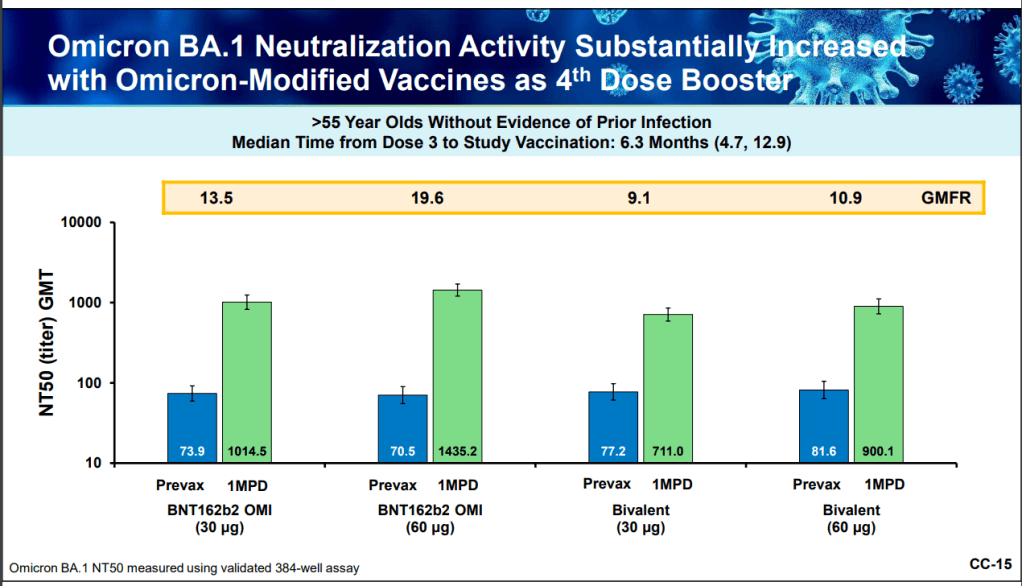

While this is an important milestone, I’d like to focus on a couple of reasons these shots are notable from a data perspective. First, the Omicron boosters are the first COVID-19 vaccines authorized in the U.S. without data from human trials. During vaccine development, companies typically start with lab studies, then test the vaccine in animal models, then in humans. Because the BA.4/BA.5 shots were designed so recently, Pfizer and Moderna haven’t had time to test them in humans yet.

From a safety and efficacy perspective, this lack of data isn’t a huge concern because the new vaccines are very close to BA.1 versions that have been tested in humans. As Katelyn Jetelina explained in a Your Local Epidemiologist post about the new vaccines:

Literally the difference of a few amino acids—like a few letter edits on a Word document. We aren’t changing the number of words in the paper (like dosage of RNA), or the content of the paper, or the platform (like Word to Excel). Because of the minimal change, we are confident that BA.1 bivalent safety data will accurately reflect BA.5 safety.

Another important piece of context here is that flu vaccines—which are updated each year to reflect currently circulating versions of the virus—are typically not tested in humans before they’re rolled out in annual flu campaigns. So, the new COVID-19 shots are following an existing process; future vaccine adjustments for new variants going forward will likely happen in a similar way.

Second, the Omicron boosters are the first COVID-19 vaccines authorized in the U.S. before they’ve been tested in other countries. For previous booster campaigns, effectiveness data from countries with better-organized health systems that started using new rounds of shots before we did (such as the U.K. and Israel) have been key for U.S. regulators making authorization decisions.

But the BA.4/BA.5 boosters haven’t been rolled out anywhere else yet. Several other countries (the E.U., the U.K., Canada, Switzerland, Australia) have authorized Omicron BA.1 boosters—those that have gone through more clinical testing. The U.S. is the first to try the BA.4/BA.5 option. It will be interesting to see whether there are significant differences in how these countries’ fall booster campaigns mitigate potential surges.

And third, these boosters are likely to be the last COVID-19 vaccines authorized while they’re still covered by federal funding. Recent announcements from officials like Ashish Jha have suggested that, in 2023, the government will stop buying vaccine supplies in large quantities to distribute for free. Instead, COVID-19 vaccines will start to be privately-purchased, health insurance-mediated products like other vaccines.

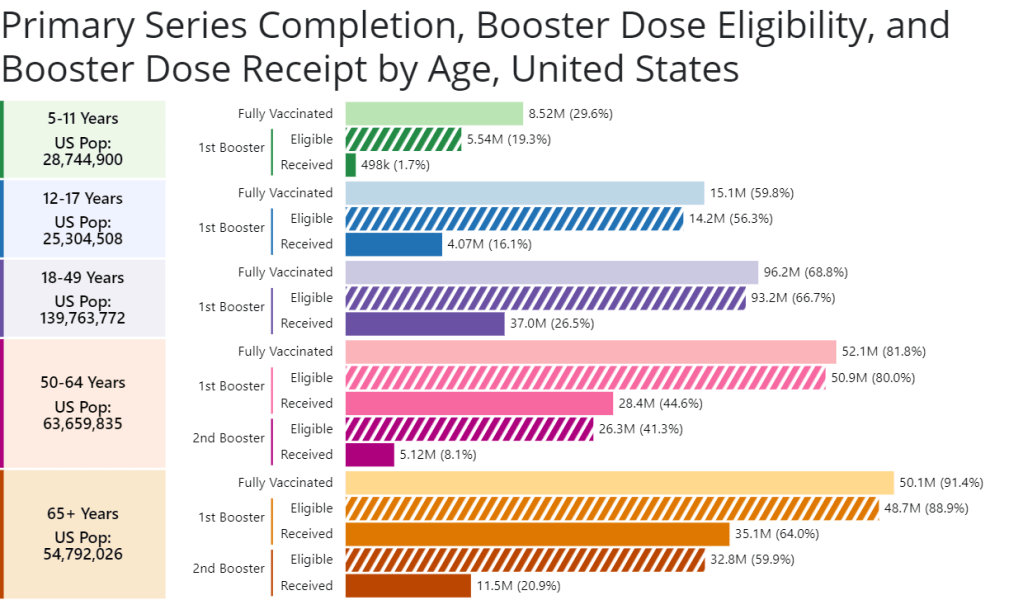

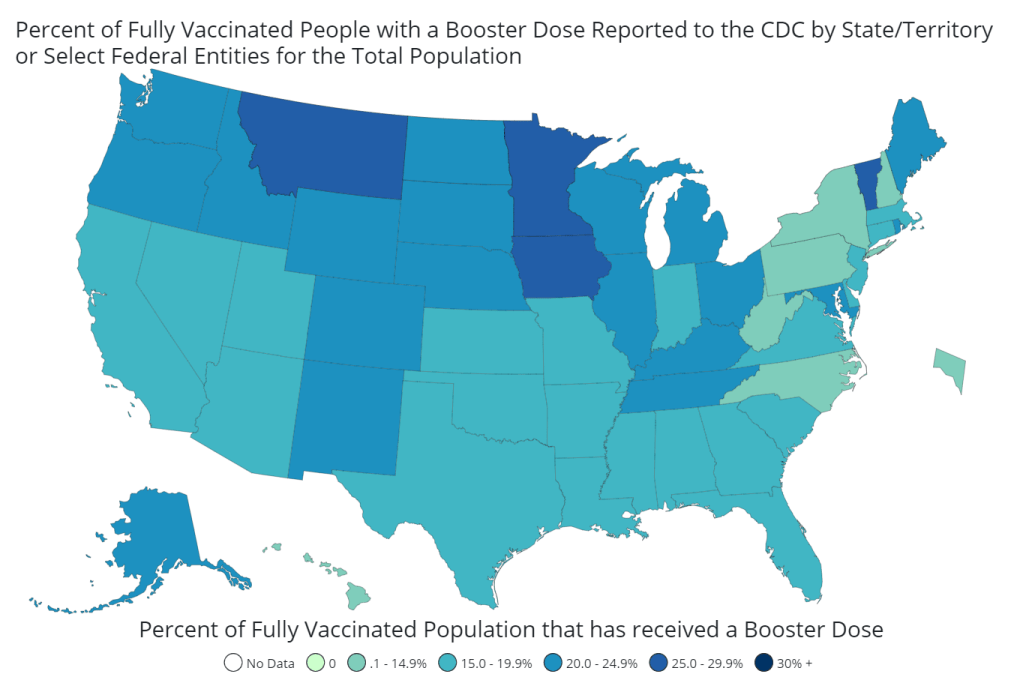

While some local governments and large health institutions will likely still organize free vaccine distributions for future rounds of shots, the lack of federal supplies will be a major shift. It will make COVID-19 vaccination harder to access, especially among people without health insurance—likely leading to even lower uptake. We need to make this last free booster campaign count.

Going forward, here are a few questions I’ll be tracking as these boosters get rolled out:

- How will public health agencies track the effectiveness of these new vaccines? We’ll want to see how the BA.4/BA.5 shots compare to prior boosters at preventing infections, hospitalizations, and deaths. Data on breakthrough cases is already pretty limited in the U.S., so we may have to rely on specific local health departments and health systems that have better infrastructure for this.

- What additional boosters might be needed in the future? As we examine how well these Omicron-specific boosters work, we will need to keep track of the potential need for more shots. Will immunocompromised people or older adults need second rounds of Omicron shots, for example?

- What new variants will come on the scene? Also impacting the potential need for further vaccine shots: the arrival of new variants, either continued Omicron mutations or something else entirely. Wastewater surveillance may be particularly helpful for variant tracking as PCR testing continues to be less available.

- How will the privatization of vaccines impact tracking? If COVID-19 vaccines are no longer purchased and distributed by the federal government after 2022, will this impact the CDC’s ability to track vaccinations? We’re already seeing more vaccine distribution at private pharmacies and doctors’ offices as opposed to publicly-run clinics; I wonder how this trend may continue.

For more information on the new boosters, check out:

- Omicron booster shots are coming—with lots of questions (Science Magazine)

- Your questions on the new Covid vaccine boosters answered (STAT News)

- What you need to know about the new omicron booster shots (Science News)

- Fall Boosters ACIP Meeting: Cliff notes (Your Local Epidemiologist)