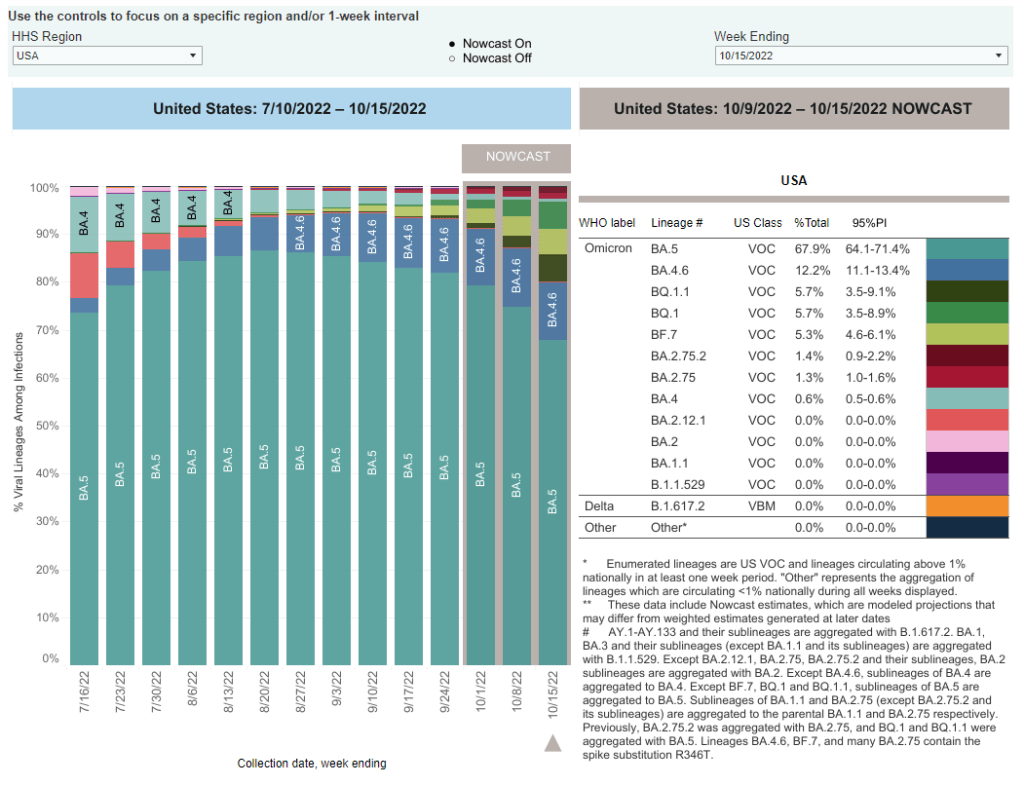

When the CDC updated its variant prevalence estimates this week, the agency added new versions of Omicron to the dashboard. In the U.S., COVID-19 cases are now driven by: BA.5, BA.4.6, BQ.1, BQ.1.1, BF.7, BA.2.75, and BA.2.75.2. And possibly more subvariants that we aren’t tracking yet.

As evolutionary biology expert T. Ryan Gregory pointed out on Twitter recently, Omicron’s evolution is “off the chart.”

Or, to parody Smash Mouth: the Omicron variants start coming and they don’t stop coming and they don’t stop coming and they don’t stop coming…

Let’s go over the veritable alphabet soup of variants we’re dealing with right now, as well as one newer variant identified in east Asia that experts are closely watching.

BA.5, BA.4, BA.4.6

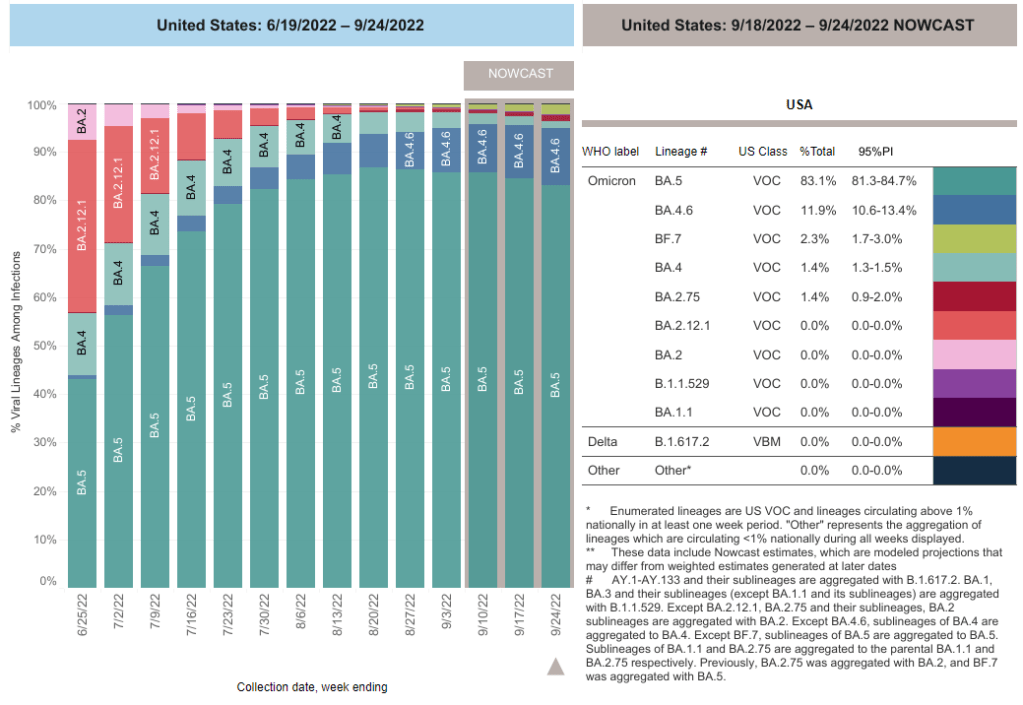

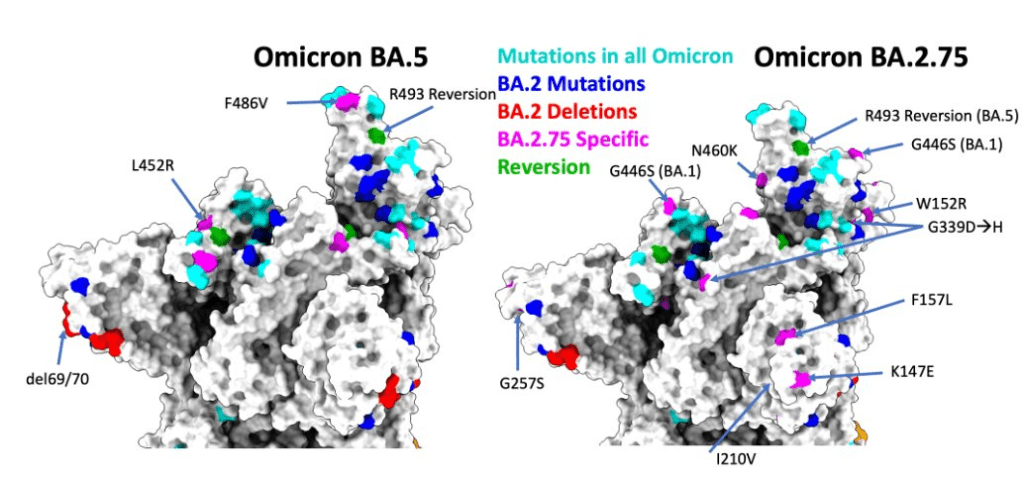

BA.5 is currently the dominant Omicron lineage in the U.S., causing about two-thirds of new COVID-19 cases in the week ending October 15. Along with BA.4, BA.5 split off from the original Omicron lineage and was first identified by South African scientists over the summer.

As these two subvariants spread around the world, it quickly became clear that they could spread faster than other versions of Omicron and reinfect people who’d previously gotten sick with those prior lineages. For more details, see this post from June. BA.5 later pulled out from BA.4 as the most competitive lineage.

BA.4.6 evolved out of BA.4. It appears to have a small advantage over BA.5, but can’t really compete with the newer subvariants we’re seeing now; according to the CDC’s estimates, it’s been causing around 10% to 12% of new cases nationwide for the last few weeks (without much growth).

BQ.1 and BQ.1.1

BQ.1 and its descendant BQ.1.1 are the two newest subvariants to show up in the CDC’s prevalence estimates, both causing about 5.7% of new cases nationwide in the last week. They actually evolved out of BA.5: BQ.1 is shorthand for a much longer, more unwieldy variant name that nobody wants to type out on Twitter.

In the U.S., BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 are starting to outcompete their parent lineage, BA.5. They’ve grown from causing less than 1% of new cases to over 10% of new cases in the last month. These subvariants are also now outcompeting other strains in the U.K. and other European countries.

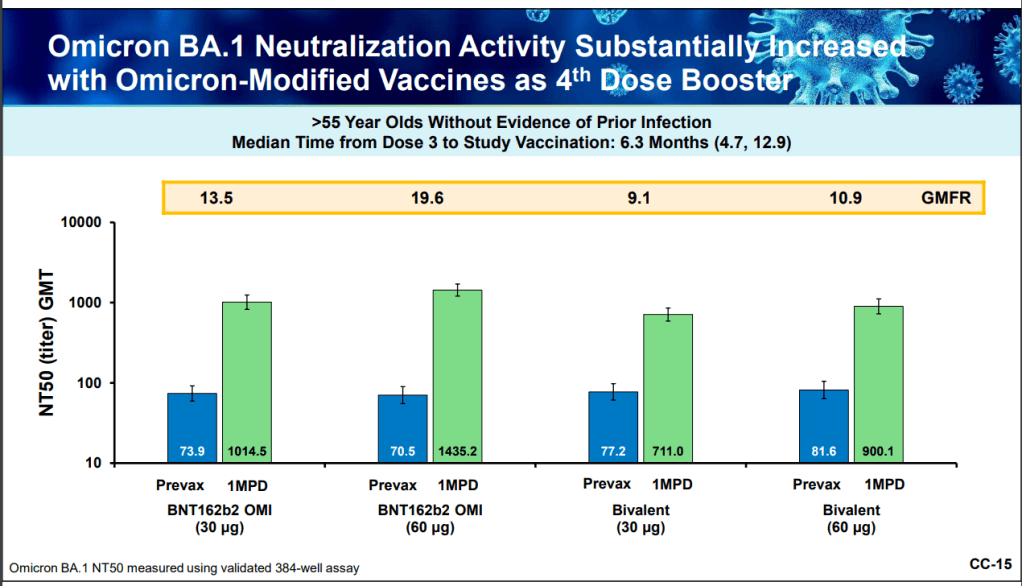

As CBS News’s Alexander Tin explains, health experts are concerned that COVID-19 treatments like monoclonal antibodies might work less well against BQ.1 and BQ.1.1. We don’t have clear data on this yet, but pharmaceutical companies will test out the newer variants in the weeks to come. The Omicron bivalent boosters, at least, are expected to continue working against this lineage.

BF.7

BF.7 is another offshoot of BA.5 (again, this is shorthand for a longer name). I dedicated a post to it in late September, and the subvariant’s position hasn’t changed significantly since then: it seems to be a bit more transmissible than BA.5, but not so much that it is quickly outcompeting the parent lineage. BF.7 caused about 5% of new cases nationwide in the last week.

Similarly to BQ.1 and BQ.1.1, there are some concerns that COVID-19 treatments will be less effective against BF.7 than other versions of Omicron based on the subvariant’s spike protein mutations, but we do not have clinical data at this point.

BA.2.75 and BA.2.75.2

BA.2.75, as you might guess from the notation, evolved out of BA.2—the same original Omicron lineage that produced BA.2.12.1 and drove surges in places like New York City over the summer. It has also remained present at fairly low levels across the U.S. recently, causing just 1.3% of new cases in the last week, according to the CDC’s estimates.

But BA.2.75 now has its own offshoot, called BA.2.75.2, that appears to be a bit more competitive. The CDC recently started splitting BA.2.75.2 out of its parent lineage in its prevalence estimates, showing that it’s growing a bit faster (from 0.4% to 1.4% in the last month). Of course, this growth rate pales in comparison to what we’re seeing from the BA.5 sublineages described above.

XBB

XBB is the latest international subvariant of concern, identified this week in several east Asian countries. It has spread particularly quickly in Singapore, as described in this article by David Axe at the Daily Beast.

Like BA.2.75, XBB descended from Omicron BA.2—though it’s gone through more rounds of spike protein mutation; this is why experts are calling it XBB, rather than a long string attached to BA.2. Data so far indicate its growth advantage over BA.5 is similar to what we’re seeing from BQ.1.1. XBB has also raised concerns about treatment and vaccine efficacy, since the bivalent boosters were developed from BA.4 and BA.5.

The CDC and other health agencies have yet to identify XBB in the U.S.; experts are closely watching how this new subvariant might be able to compete with our current variations on BA.5.

Overall takeaways

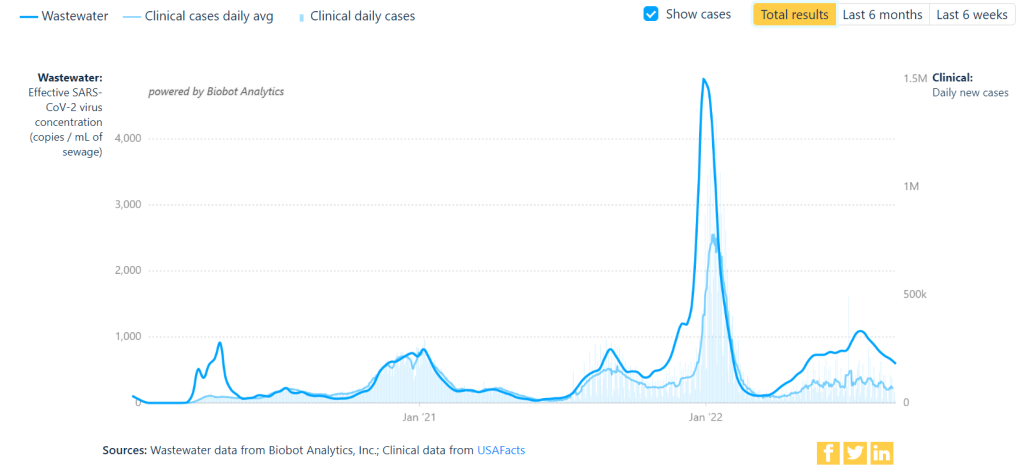

Overall, both in the U.S. and around the world, we’re seeing a lot of competition between these subvariants. All of them have small growth advantages over BA.5—which is currently dominant in the U.S.—but none are so different that they’re completely pulling ahead.

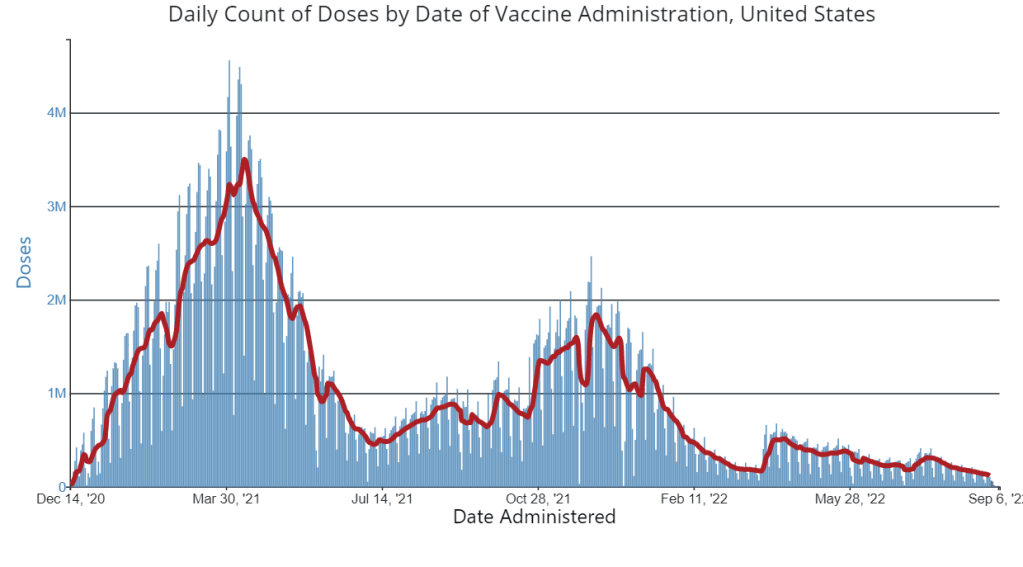

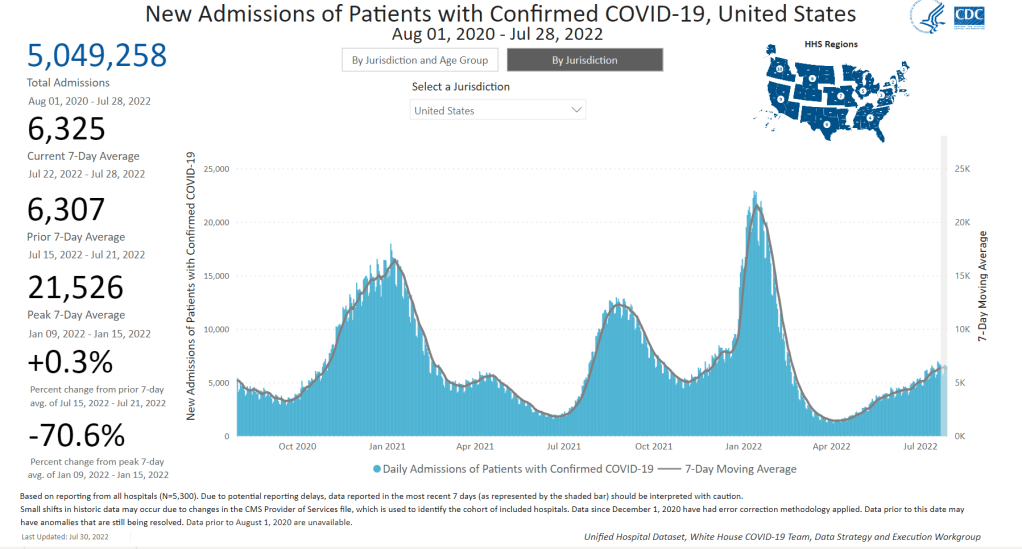

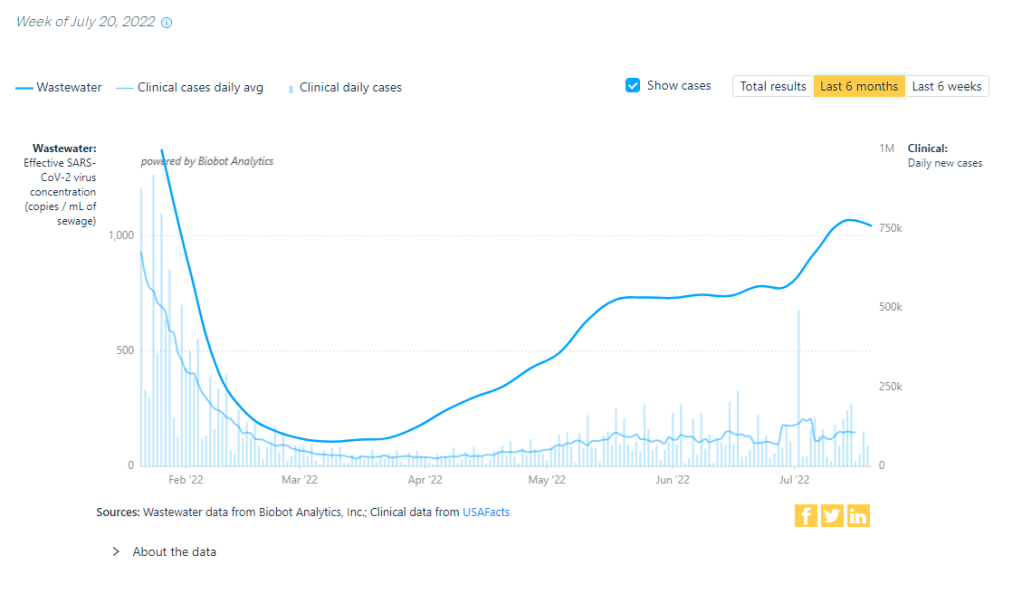

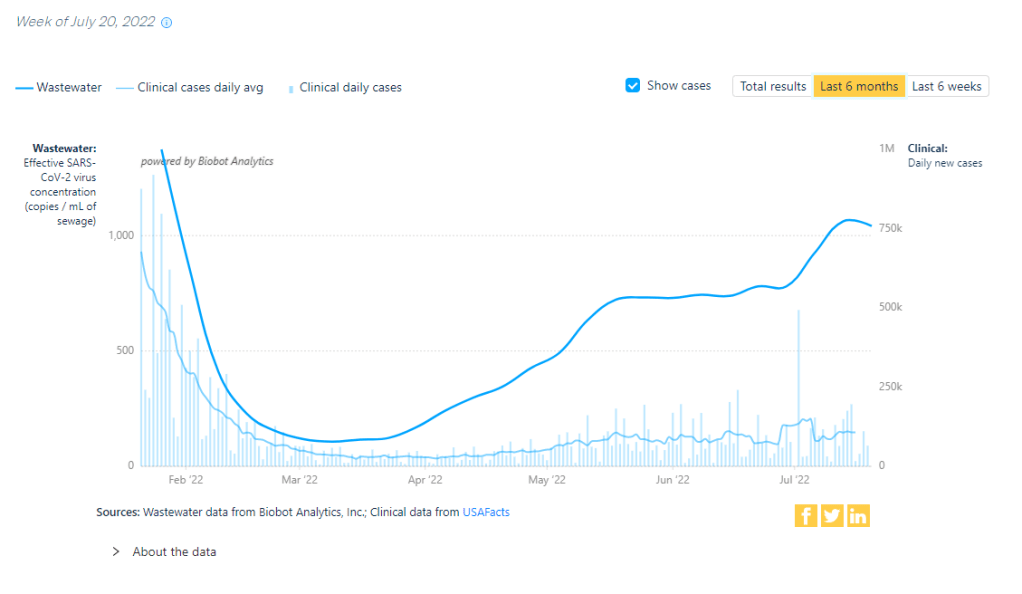

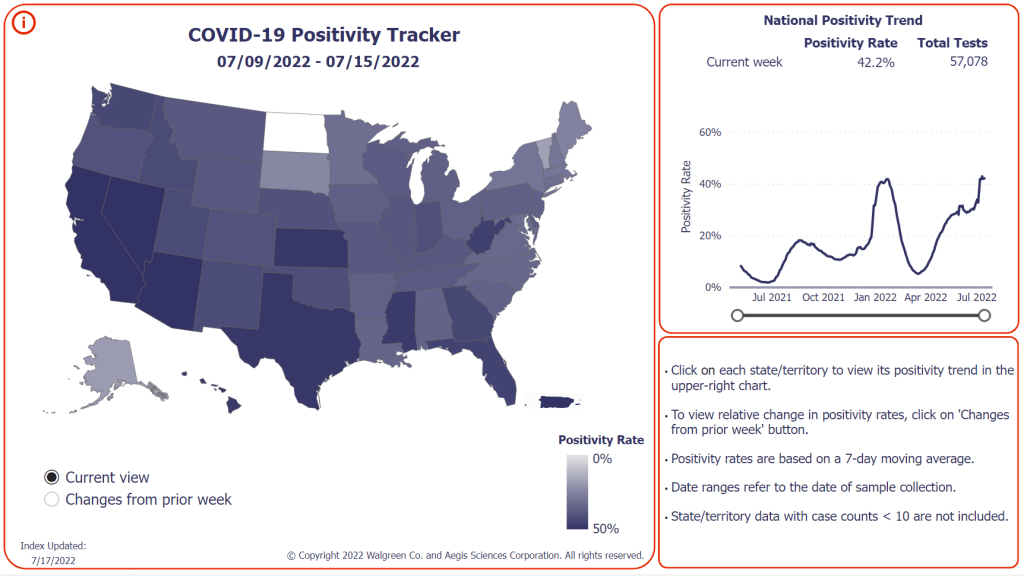

As I wrote last weekend, many experts are anticipating a surge this fall and winter, driven by both new subvariants and less-cautious beavior. We likely won’t see a huge spike at the level of last winter’s massive Omicron surge, but this season will still have plenty of infections (and reinfections).

We will need more data on how all these newer variants respond to vaccines and treatments, especially the antiviral Paxlovid. But it’s at least promising that many of the circulating variants right now evolved from BA.5, against which our bivalent boosters were specifically designed. It’s a great time to get that booster!