!function(){“use strict”;window.addEventListener(“message”,(function(a){if(void 0!==a.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var e in a.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var t=document.getElementById(“datawrapper-chart-“+e)||document.querySelector(“iframe[src*=’”+e+”‘]”);t&&(t.style.height=a.data[“datawrapper-height”][e]+”px”)}}))}();

Back in September, I read the Interim COVID-19 Vaccination Playbook released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—the first national plan for how vaccination was supposed to proceed. Here’s an excerpt from my newsletter issue covering this playbook:

Once COVID-19 vaccination begins, the CDC will report national vaccination data on a dashboard similar to the agency’s existing flu vaccination dashboard. According to the playbook, this dashboard will include estimates of the critical populations that will be prioritized for vaccination, locations of CDC-approved vaccine providers and their available supplies, and counts of how many vaccines have been administered.

This past week, the first COVID-19 vaccine doses were administered to frontline healthcare workers across the country. The FDA issued Emergency Use Authorization to a second vaccine. But I haven’t seen a vaccination dashboard from the CDC; the closest we’ve come so far is a dataset listing initial allocations of Pfizer doses for every state. This federal agency is lagging behind several states that are making their vaccination counts public, as well as journalists who have already begun to compile the limited information that’s available.

Here’s how the reporting of vaccination data is supposed to work. When someone goes in to get their COVID-19 shot, the provider of that shot will enter their name and other personal information to a state registry called an Immunization Information System, or IIS. Vaccine providers that issue shots and send data may include hospitals, clinics, pharmacies, pop-up vaccination sites, and any other institution that is giving shots.

Most states and several large cities, like New York City, have these immunization registries; New Hampshire is still getting its registry ready to track COVID-19 vaccines. The registries stay private, with data only available for the people who ship, administer, and manage vaccines. A data system called the IZ gateway will help different state immunization systems link up with each other and with the CDC, which has asked all states to formally agree to share their data with this federal agency. (The CDC has asked states to share a pretty extensive list of data points for each vaccine patient, including names and addresses, which some states are not willing to send.)

The CDC has also developed a system to help vaccine providers manage supplies and patients, a public-facing website that will help Americans see where they can get vaccinated, and a new software that will pull all vaccine-related information into one place for Operation Warp Speed officials to use. Finally, an HHS data system called the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System will collect information on patient reactions to the vaccines, such as headaches and fatigue—both of which are expected reactions to the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines.

For more detail on these data systems, see this article by USA TODAY’s Aleszu Bajak and Janet Loehrke, which I drew upon to write this part of the newsletter.

Theoretically, the CDC should have precise counts of how many people have received vaccine doses in every state, as well as personal identifying information for all of those people. So far, however, it appears that many states are beginning to make these data public, while the federal government has yet to release national numbers.

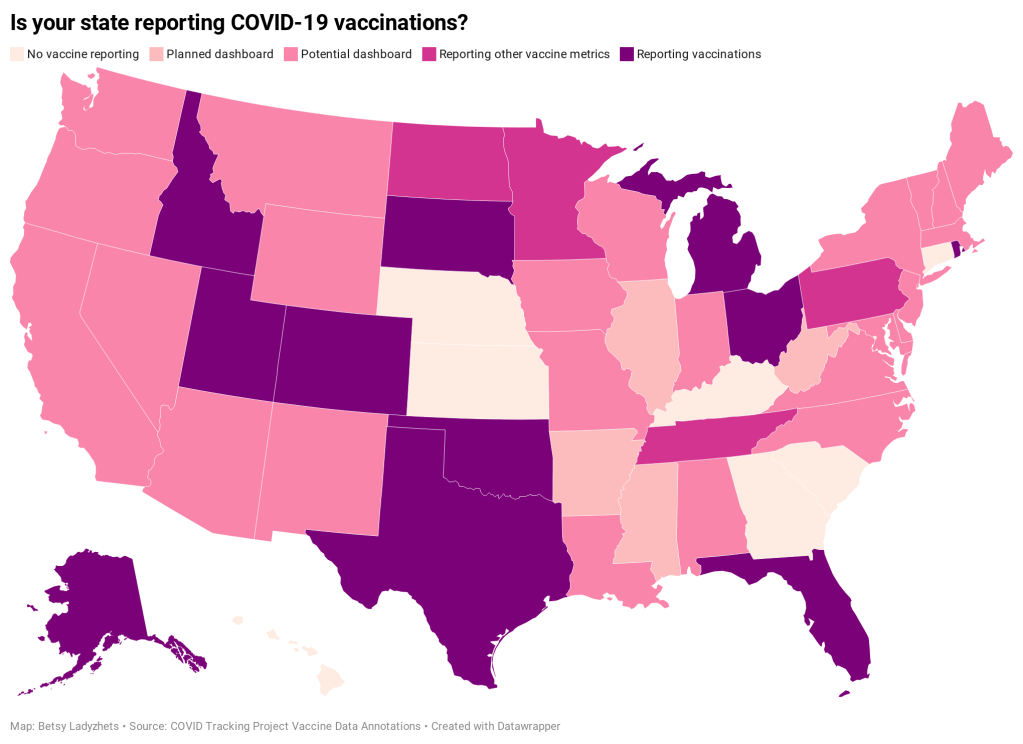

According to ongoing analysis by the COVID Tracking Project, 15 states are reporting some form of vaccination data as of December 19. Here’s the breakdown:

- Five states have added a count of vaccine doses administered as a single metric on their dashboards: Alaska, Colorado, Idaho, Oklahoma, and Rhode Island.

- Two states have added vaccination-specific pages to their dashboards: South Dakota and Utah.

- Three states have built entirely new dashboards for vaccination: Michigan, Ohio, and Texas.

- Florida is releasing daily vaccination reports.

- Four states are reporting vaccine-related metrics (such as counts of approved providers and doses delivered) that don’t yet include actual counts of the doses administered: Minnesota, Pennsylvania, North Dakota, and Tennessee.

- Five states are reporting some form of demographic data: Michigan reports vaccinations by age; Texas reports by county; Utah reports by local health jurisdiction; Ohio reports by age and county; South Dakota reports by age, gender, and county; and Florida reports by race, age, gender, and county.

For links to all of these states’ dashboards and reports, see the COVID Tracking Project’s annotations.

Florida is the only state to report vaccination counts broken down by race so far, though the state has not yet reported such counts for different ethnicities. Public health experts have widely agreed that people of color—especially Black Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanic/Latino Americans—should be prioritized in COVID-19 vaccination because these communities have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. But without knowing vaccination rates in these vulnerable communities, it will be impossible to determine whether they are receiving the medical treatment they deserve.

A recent article by ProPublica’s Caroline Chen, Ryan Gabrielson, and Topher Sanders calls attention to the lack of standardization that currently exists for state collection of race and ethnicity data:

In state vaccination registries, race and ethnicity fields are simply considered “nice to have,” explained Mitchel Rothholz, chief of governance and state affiliates for the American Pharmacists Association. While other fields are mandatory, such as the patient’s contact information and date of birth, leaving race and ethnicity blank “won’t keep a provider from submitting the data if they don’t have it.”

In other words, if a Black woman gets the Moderna vaccine at a Walgreens in Brooklyn, she could feel uncomfortable disclosing her race on the pharmacy’s form—and little action would be taken to explain to her why such disclosure is important and how her information would be used. The “race” checkbox on her form would be left blank. She would likely go uncounted by researchers and journalists trying to hold the government accountable to its promises of equity.

The federal government should be both more rigorous in requiring race and ethnicity data and more transparent in disclosing these data—but I’d take a simple, national count of how many people in America have received COVID-19 shots to start. Recent data releases from the HHS have made me pretty optimistic about the federal public health agency’s ability to be transparent (see: the next two sections of this issue.) But the lack of a federal dataset so far means that key COVID-19 information is once again scattered.

In a Poynter webinar last week, Al Thompkins asked a panel of top infectious disease experts—including scientists on both the FDA’s and the CDC’s vaccine advisory panels—a simple question: Will the public be able to see counts of how many people are getting vaccinated? None of those experts had a clear answer. There may be a dashboard in the works behind the scenes of which the panelists hadn’t been informed, but their responses still did not inspire confidence.

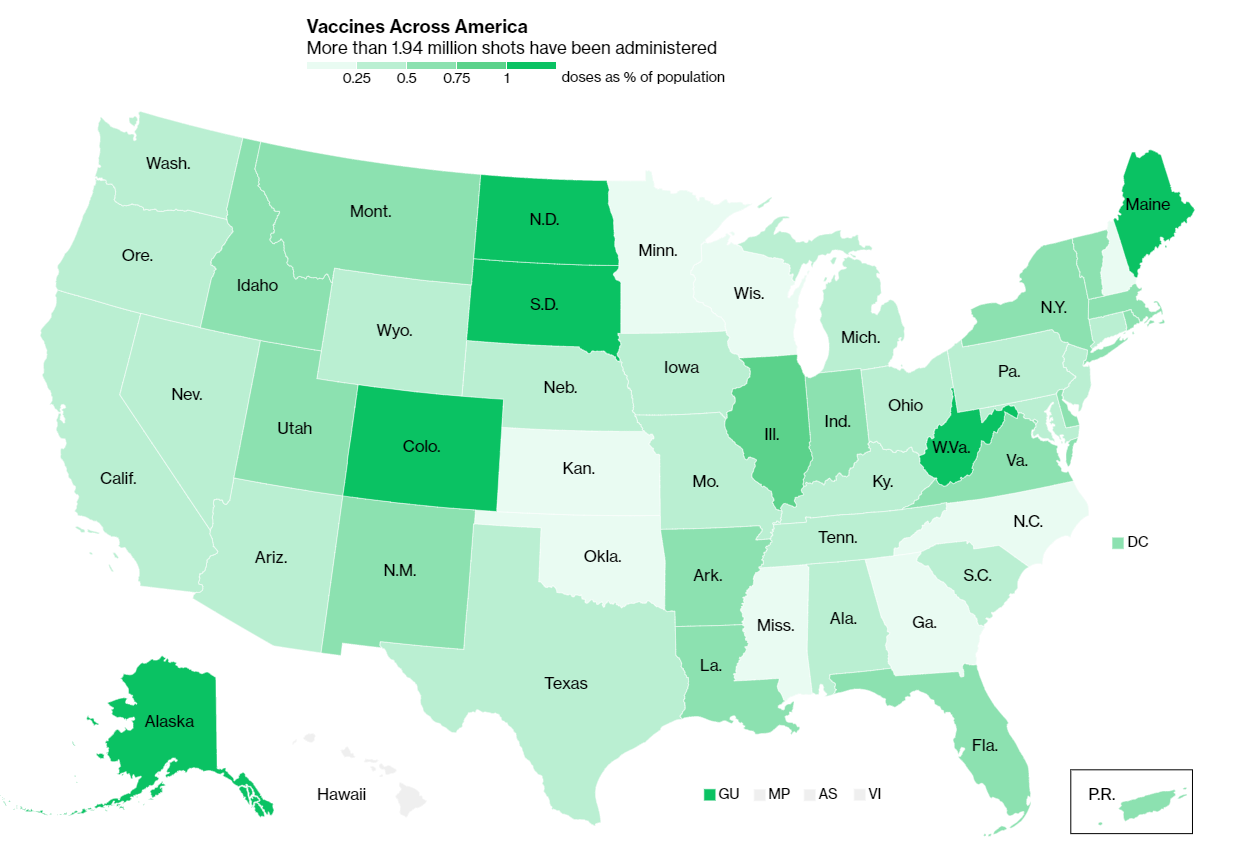

Of course, journalists are once again stepping in to cobble together vaccination counts from all the public sources they can find. Bloomberg has counted 211,000 Pfizer doses in the U.S., as of December 19, by compiling numbers from state websites, press conferences, and interviews. The New York Times has surveyed state public health departments. Benjy Renton continues to update a Tableau dashboard that compares planned Pfizer and Moderna shipments to state populations.

And the Kaiser Family Foundation released its COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor, an ongoing project to track public perception of and experiences with vaccination. The latest survey from this monitor shows that 71% of Americans would “definitely or probably” get a vaccine for COVID-19 if it was determined to be safe and freely available.

This week, as I’ve seen the vaccination numbers—and the photos of frontline healthcare workers getting these well-deserved shots—I’ve felt something strange. Something hopeful. For the first time since March, I’m looking at numbers that I actually want to see go up. Now, if we could just get more comprehensive numbers, and get them more standardized, and get them reported with a priority on racial justice…