Earlier this month, the CDC made a pretty significant change in how it tracks breakthrough cases. Instead of reporting all cases, the agency is only investigating and collecting data on those cases that result in hospitalizations or deaths.

In case you need a refresher: “breakthrough cases” are those infections that occur after a patient is fully vaccinated (including both doses, if applicable, and the two-week waiting period after a final dose). These cases are rare—like, one in ten thousand rare. As I wrote back in April, it’s important to contextualize any reporting on these cases with their incredible rareness so that we hammer home just how effective the vaccines are.

But just because breakthrough cases are rare doesn’t mean we shouldn’t pay attention to them. In fact, it’s critical to pay attention to these cases in order to monitor precisely how well our vaccines are working—and how new variants may threaten the protections those vaccines provide.

As The Atlantic’s Katherine J. Wu explains:

Breakthroughs can offer a unique wellspring of data. Ferreting them out will help researchers confirm the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines, detect coronavirus variants that could evade our immune defenses, and estimate when we might need our next round of shots—if we do at all.

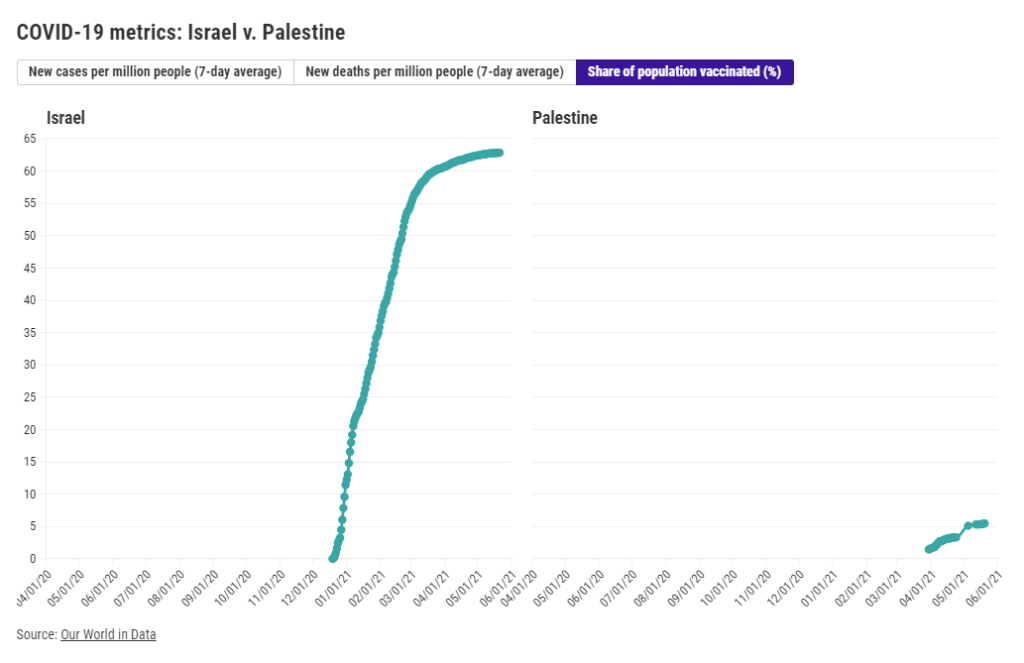

As I’ve discussed in past variant reporting, numerous studies have demonstrated that the vaccines currently in use in the U.S.—especially the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines—work well against all variants. That includes variants of concern, such as B.1.617 (from India), B.1.351 (from South Africa), and P.1 (from Brazil). But the vaccine efficacy rates for some of these variants are lower than that stellar 95% we saw in Pfizer and Moderna’s clinical trials. And some common therapeutic drugs don’t work well for patients infected with variants, too.

As a result, scientists are concerned that, while the vaccines are working well now, they might not work well forever. Whenever the coronavirus infects a new person, it has the opportunity to evolve. And that continued evolution must be monitored. The first coronavirus variant able to evade our vaccines may emerge in a foreign country with a raging outbreak—but it may also emerge here in the U.S. Closely monitoring all breakthrough cases will help us find that dangerous variant.

(Of note: A new, potentially-concerning variant was identified just last night in Vietnam; WHO scientist Maria Van Kerkhove described it as an offshoot of the variant from India, B.1.617, with “additional mutation(s).”)

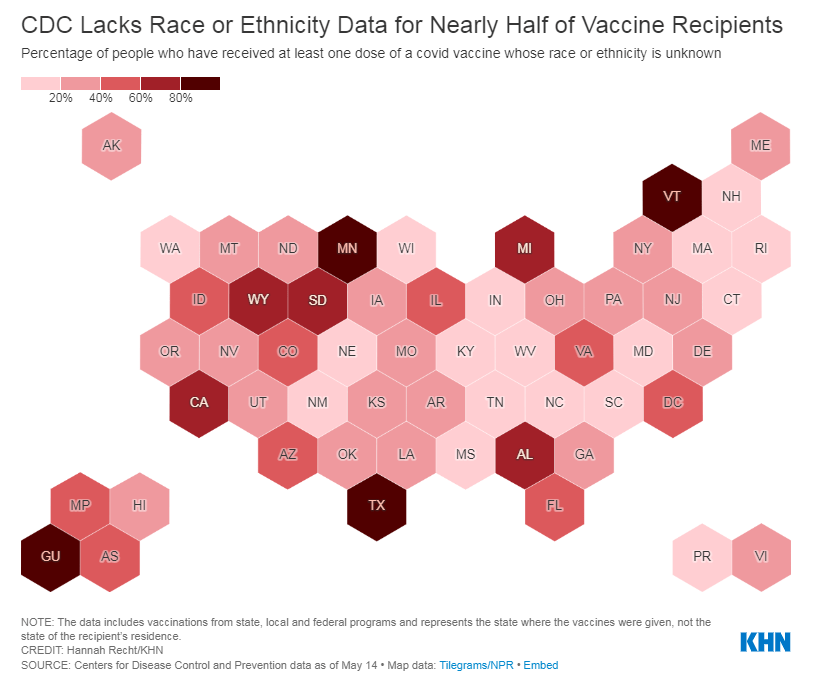

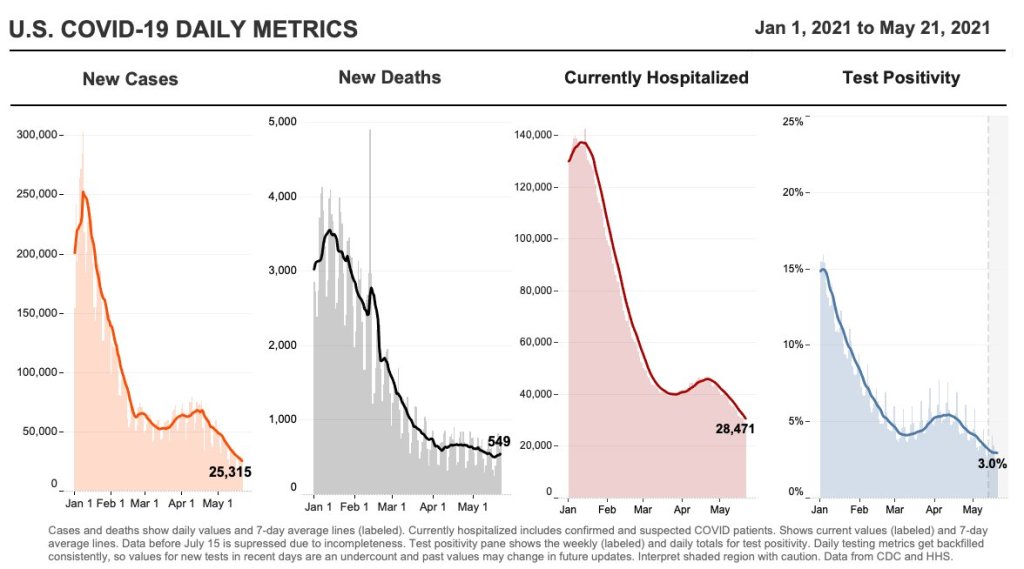

With that in mind, let’s unpack the CDC’s reporting change. When the vaccine rollout started, the agency was investigating all breakthrough cases that came to its attention—including those in patients with only mild symptoms, or with no symptoms at all. According to an agency study released this past Tuesday, the CDC identified 10,262 such breakthrough cases from 46 U.S. states and territories between January 1 and April 30, 2021.

Keep in mind: By April 30, about 108 million Americans had been fully vaccinated. Dividing 10,262 by 108 million is where I got that “one in ten thousand” comparison I cited earlier. As I said: very rare.

Starting on May 1, however, the CDC changed its strategy. Now, it is only tracking breakthrough cases that result in severe illness for patients, leading to hospitalization and/or death. The CDC says that this choice is intended to focus on “the cases of highest clinical and public health significance” rather than tracking down asymptomatic cases.

In its May 25 report, CDC scientists said that 27% of the breakthrough cases identified before May 1 were asymptomatic. 10% of the infected individuals were hospitalized, though almost a third of those patients were hospitalized for a reason unrelated to COVID-19. Only 160 patients (less than 2% of the breakthrough cases) died.

We need to take these numbers with a grain of salt, though, because the CDC has likely undercounted the true number of asymptomatic cases. Both clinical trials and studies on vaccine effectiveness in the real world have suggested that those people who get infected with COVID-19 after completing a vaccination regime are more likely to have mild symptoms, or no symptoms at all.

Plus, the CDC is recommending that vaccinated Americans don’t need to get tested before traveling, if they have come into contact with someone known to have COVID-19, or for many of the other reasons that many of us got tested this past year. (The agency is still recommending that fully vaccinated people get tested if they’re experiencing COVID-19 symptoms, though.)

As I wrote at Slate Future Tense last month, such guidelines are likely to drive down the number of COVID-19 tests conducted across the U.S. And this trend seems to be happening, so far: PCR tests dropped from their winter surge levels this spring, and are now dropping again. (Antigen and other rapid tests may be getting used more, but we don’t have any comprehensive data on them.)

With that drop in testing—combined with the overall challenge of identifying asymptomatic COVID-19 cases outside of dedicated studies—it would be pretty damn hard for the CDC to track down all breakthrough cases. The agency’s focus on more serious cases instead may thus be considered a conservation of resources, directing research efforts and care to those Americans who get seriously ill after vaccination.

But “a conservation of resources” is also a nice way of saying, the CDC made a lazy choice here. The agency has poured money into genomic surveillance over the past few months, sequencing over 20,000 cases a week (compared to a few thousand cases a week before Biden took office). In recent weeks, the Biden administration has announced renewed funding for public health and similar commitments to prioritizing scientific research. If the CDC wants to find and sequence breakthrough cases in order to identify vaccine-busting variants, there should be nothing stopping the agency.

Or, as epidemiologist Dr. Ali Mokdad told the New York Times: “The C.D.C. is a surveillance agency. How can you do surveillance and pick one number and not look at the whole?”

Out of those 10,262 cases that the CDC reported this week, only 5% had sequence data available—but the majority of those sequined cases were variants of concern, including B.1.1.7 and P.1. At The Atlantic, Wu reported that epidemiologists in some parts of the country are seeing more breakthrough cases tied to concerning variants, while others are seeing breakthrough case sequences that match the overall infections in the community.

To me, this high level of unknowns and uncertainties mean that we need more breakthrough case reporting and sequencing, not less. And we need a national public health agency that commits to true surveillance, so that we aren’t flying blind when the coronavirus inevitably evolves beyond our current defenses.

(P.S. Shout-out to Illinois, the one state that reports its own breakthrough case data.)

More vaccine reporting

- Sources and updates, November 12Sources and updates for the week of November 12 include new vaccination data, a rapid test receiving FDA approval, treatment guidelines, and more.

- How is the CDC tracking the latest round of COVID-19 vaccines?Following the end of the federal public health emergency in May, the CDC has lost its authority to collect vaccination data from all state and local health agencies that keep immunization records. As a result, the CDC is no longer providing comprehensive vaccination numbers on its COVID-19 dashboards. But we still have some information about this year’s vaccination campaign, thanks to continued CDC efforts as well as reporting by other health agencies and research organizations.

- Sources and updates, October 8Sources and updates for the week of October 8 include new papers about booster shot uptake, at-home tests, and Long COVID symptoms.

- COVID source shout-out: Novavax’s booster is now availableThis week, the FDA authorized Novavax’s updated COVID-19 vaccine. Here’s why some people are excited to get Novavax’s vaccine this fall, as opposed to Pfizer’s or Moderna’s.

- COVID-19 vaccine issues: Stories from COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers across the U.S.Last week, I asked you, COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers, to send me your stories of challenges you experienced when trying to get this fall’s COVID-19 vaccines. I received 35 responses from readers across the country, demonstrating issues with insurance coverage, pharmacy logistics, and more.