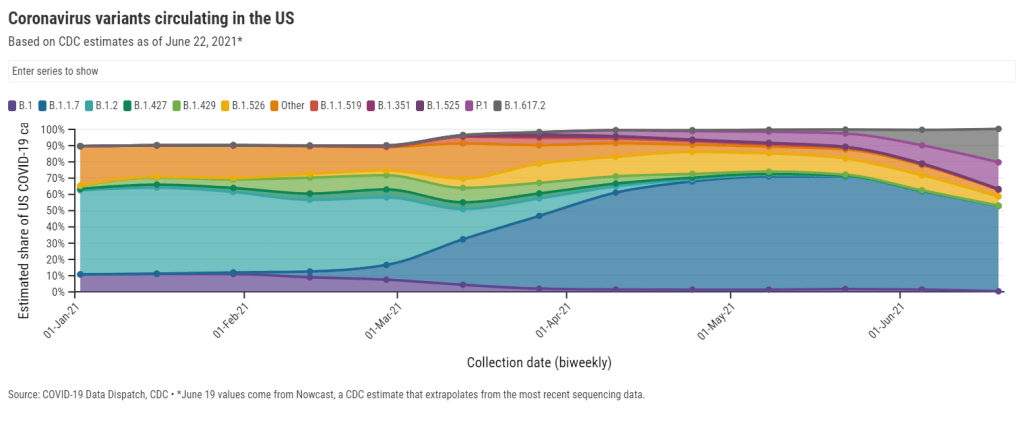

For the past few months, we’ve been watching the vaccines and variants race in real time. With every new case, the coronavirus has the opportunity to mutate—and many scientists agree that it will inevitably mutate into a viral variant capable of outsmarting our current vaccines.

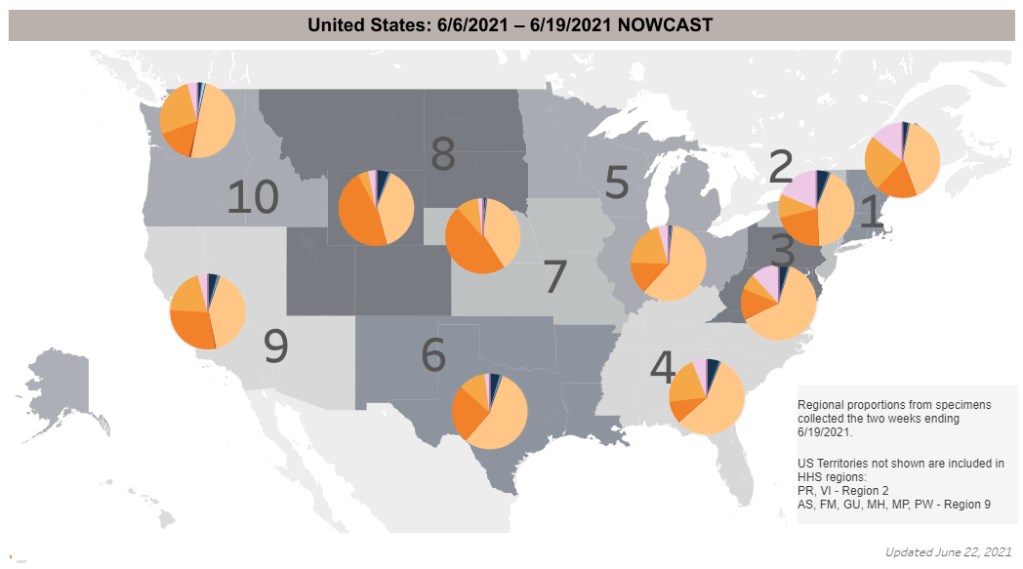

How will we know when that happens? Through genomic surveillance, examining the structure of coronavirus lineages that arise in the U.S. and globally. While epidemiologists may consider any new outbreak a possible source of new variants, one key way to monitor the virus/variant race is by analyzing breakthrough cases—those infections that occur after someone has been fully vaccinated.

In May, the CDC changed how it tracks breakthrough cases: the agency now only investigates and reports those breakthrough cases that result in hospitalizations or deaths. I wrote about this in May, but a new analysis from COVID Tracking Project alums and the Rockefeller Foundation provides more detail on the situation.

A couple of highlights from this new analysis:

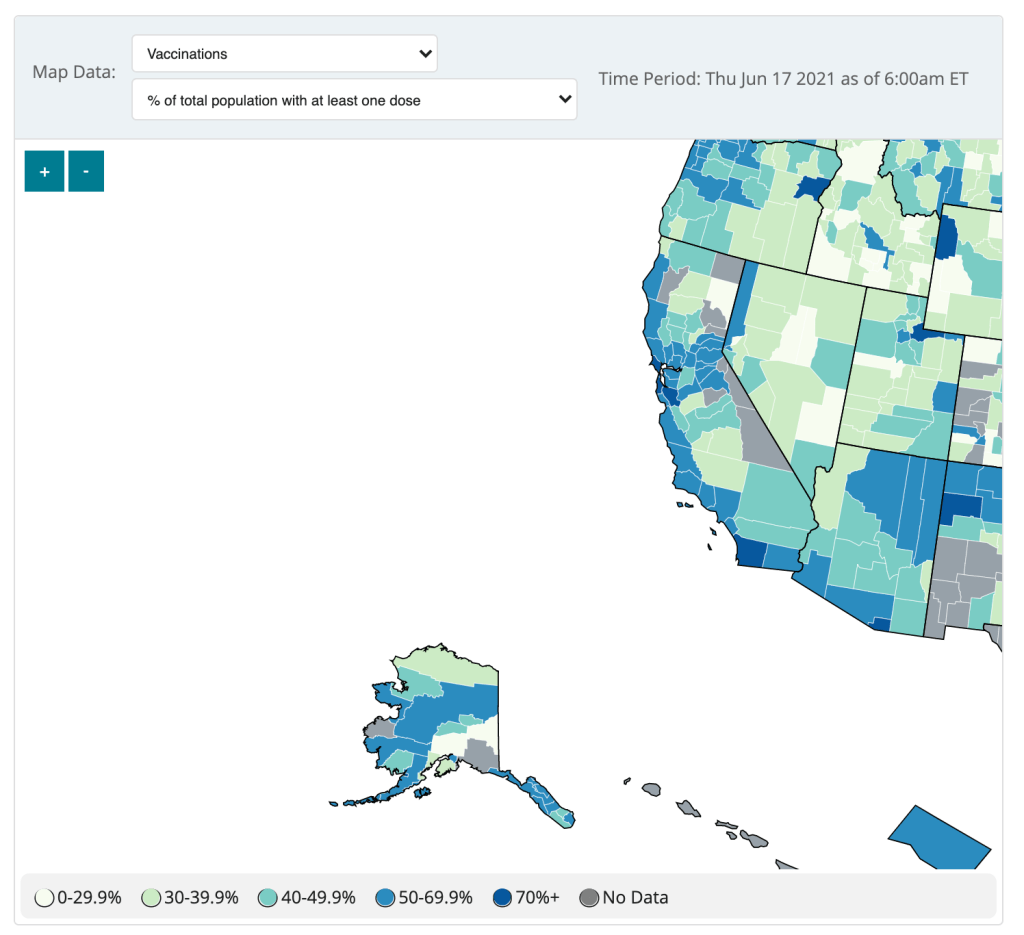

- 15 states regularly report some degree of information about vaccine breakthroughs, some including hospitalizations and deaths.

- Six states report sequencing results identifying viral lineages of their breakthrough cases: Nebraska, Arkansas, Alaska, Montana, Oregon, and Washington.

- Washington and Oregon are unique in providing limited demographic data about their breakthrough cases.

- Several more states have reported breakthrough cases in isolated press briefings or media reports, rather than including this vital information in regular reports or on dashboards.

- When the CDC stopped reporting breakthrough infections that did not result in severe disease, the number of breakthrough cases reported dropped dramatically.

- We need more data collection and reporting about these cases, on both state and federal levels. Better coordination between healthcare facilities, laboratories, and public health agencies would help.

Vaccine breakthrough cases are kind-of a data black box right now. We don’t know exactly how many are happening, where they are, or—most importantly—which variants they’re tied to. The Rockefeller Foundation is working to increase global collaboration for genomic sequencing and data sharing via a new Pandemic Prevention Institute.

Luckily, there is a lot we do know from another side of the vaccine/variant race: vaccine studies have consistently brought good news about how well our current vaccines work against variants. The mRNA vaccines in particular are highly effective, especially after one has completed a two-dose regimen. If you’d like more details, watch Dr. Anthony Fauci in Thursday’s White House COVID-19 briefing, starting about 14 minutes in.

New research, out this week, confirmed that even the one-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine works well against the Delta variant. The company reported that, after a patient receives this vaccine, blood antibody levels are high enough to beat off an infection from Delta. In other words, people who got the J&J shot do not need to rush to get a booster shot from an mRNA vaccine (a recent debate topic among some experts).

Again, we’ll need more genomic surveillance to carefully watch for the variant that inevitably does beat our vaccines. But for now, the vaccinated are safe from variants—and getting vaccinated remains the top protection for those who aren’t yet.