When faced with entrenched disparities and a local government that doesn’t want to confront them, it can be difficult for singular individuals to step in and fill gaps. But the founders of NYC Vaccine List knew they could fill one specific gap: they built a better website for finding vaccination appointments.

The NYC Vaccine List website is simple—simpler than the official city site. Just go to the homepage, scroll past the instructions, and you’ll find a list of vaccine locations. For each location, the site clearly marks available appointments or, where this information can’t be automatically pulled in, provides a link to the location’s website and a note from the last NYC Vaccine List volunteer who checked it. When I checked it at about midnight this morning, Yankee Stadium appointments (for Bronx residents only) were at the top of the list.

I talked to Dan Benamy and Michael Kuznetsov, two of the founders of this project, over email last week; they told me more about how the NYC Vaccine List website works and their efforts to improve its functionality for all New Yorkers. This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Betsy Ladyzhets: I know the basics of the project’s methodology—you’re scraping the websites of different vaccination sites and compiling all the info in one place. But I’d like to know more about what running this site actually looks like on a day-to-day basis. What parts of the project are manual vs. automated? Are there regular hours that you work on updates?

NYC Vaccine List: The project is managed through a Discord chat server, which makes it possible for volunteers to communicate about certain topics in a group chat, as well as one-on-one when needed. Various responsibilities have been parcelled out to different volunteers based on their ability to help in different areas: maintaining the crawlers, calling to verify information that cannot be crawled, and reaching out to local organizations and press to help spread the word about the project. There are no fixed hours—as this is an all-volunteer effort, we fit this work in between our responsibilities to work and family. This means that it’s not that unusual for there to be work done well into the early hours of the morning!

BL: I saw on Twitter that you’re working on providing translations to make the site accessible in languages other than English. How is that going so far? Have you noticed any changes in the people using the site thanks to this change?

NYC VL: As of this week, the site can be translated on-demand using the “Language” button in the upper right hand corner of the site. We use the Google Translate widget, which is the same technology used by NYC.gov. The Google Translate widget is provided free-of-charge to COVID-related efforts. Our volunteers have reached out to friends and family to validate the translations, and received positive feedback that the translations make the site easier to use for a non-English speaker.

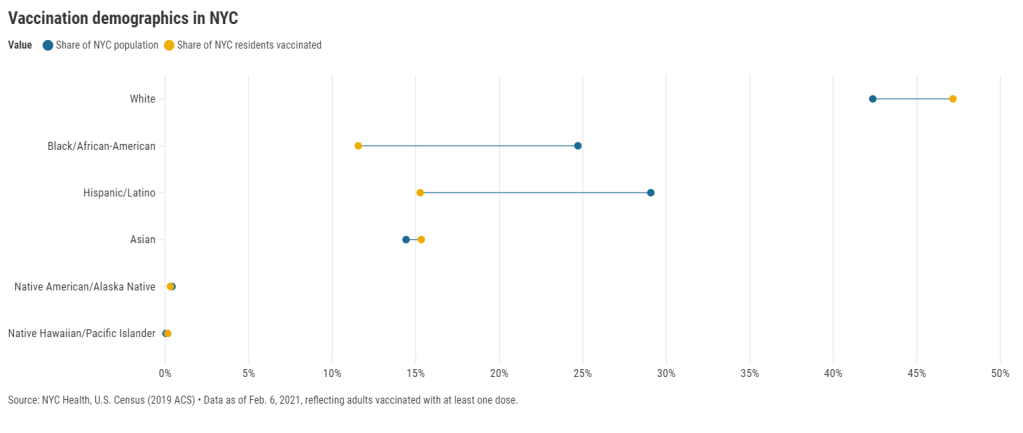

BL: So far, white New Yorkers are getting vaccinated at disproportionately high rates while Black and Latino New Yorkers are getting vaccinated at disproportionately low rates. What can the city do to make vaccination appointments more accessible for these groups? What role do you see your project playing in addressing this issue?

NYC VL: The social and epidemiological questions that come along with a mass vaccination effort are complex, and although we have volunteers that have experience in this realm, our organization is not in a position to make recommendations to the city. We hope to increase access to the vaccine by removing the burden of navigating dozens of websites and waiting for hours on hold in order to find a vaccine.

We have two simultaneous efforts that strive to make the site more equitable to all residents: First, we’ve prioritized technical fixes that make the site usable for non-English speakers, those with slow internet, those that cannot easily travel across the city, and those relying on screen-readers. Second, we’ve reached out to organizations around the city that directly work with underserved communities. In that outreach, we’ve made sure that the organizations are aware of our site, as well as that they have a direct line of communication back to us in case there is a way to improve the site for their communities and constituents.

BL: The city revamped its own vaccine portal recently; the updated site at least appears to be easier to use. Has this update impacted your project?

NYC VL: The new site is a big step in the right direction, and we’re thrilled to see it because it means more New Yorkers can easily find an appointment. First and foremost, the site should be usable for New Yorkers that visit it directly. Any challenges that we encounter while trying to visit it automatically are secondary, so we don’t have any gripes related to how the page is coded. We’re continuing our efforts to build a site that encompasses all available vaccine locations and appointments available to New Yorkers, which the new site does not yet do, and remain hopeful that the city will continue to make progress in this domain.

BL: What are your future plans for the project? Do you see yourselves keeping this going through future phases of vaccination?

NYC VL: At this point, we haven’t made future plans for the project. We’re energized by the short-term impact we’ve been able to make, and are hopeful that our project won’t be needed for much longer.

BL: What has been your favorite story so far of someone using the website to find an appointment?

NYC VL: We have a new favorite story every day, but one that came in a few minutes ago is top of mind: “Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. A lung transplant makes me a high-risk individual but the ways things are set up, my doctors could not help me get the vaccine. … NYC Vaccine List might literally be my lifesaver. I got my first shot yesterday, Feb. 3, after I spotted an opening on your site at 1:20 a.m. that morning. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.”

Related posts

- Sources and updates, November 12Sources and updates for the week of November 12 include new vaccination data, a rapid test receiving FDA approval, treatment guidelines, and more.

- How is the CDC tracking the latest round of COVID-19 vaccines?Following the end of the federal public health emergency in May, the CDC has lost its authority to collect vaccination data from all state and local health agencies that keep immunization records. As a result, the CDC is no longer providing comprehensive vaccination numbers on its COVID-19 dashboards. But we still have some information about this year’s vaccination campaign, thanks to continued CDC efforts as well as reporting by other health agencies and research organizations.

- Sources and updates, October 8Sources and updates for the week of October 8 include new papers about booster shot uptake, at-home tests, and Long COVID symptoms.

- COVID source shout-out: Novavax’s booster is now availableThis week, the FDA authorized Novavax’s updated COVID-19 vaccine. Here’s why some people are excited to get Novavax’s vaccine this fall, as opposed to Pfizer’s or Moderna’s.