The U.S. is heading into our first winter since the end of the federal public health emergency for COVID-19. Those of us still following COVID-19 trends might need to change which data sources we use to track the disease this winter, and how we think about trends.

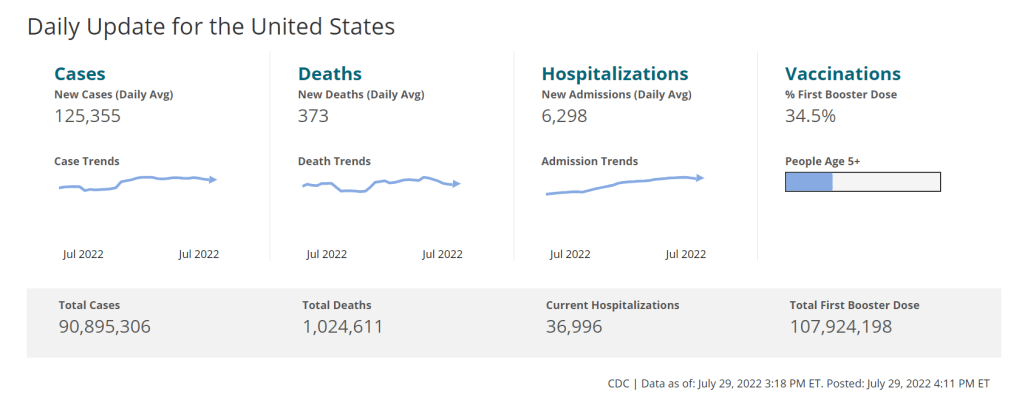

The pandemic certainly hasn’t ended: COVID-19 still leads to hundreds of hospitalizations and deaths each day, not to mention millions with Long COVID. Since the U.S. government ended its emergency response to this disease, we now have significantly less information—but not zero information—about how it’s spreading.

To recap the key changes to COVID-19 data following the emergency’s end (see this post from May for more details):

- The CDC is no longer collecting case data, as it lost authority to require reporting from PCR testing labs.

- Following the CDC’s lead, many state and local health departments have also stopped tracking COVID-19 cases.

- The CDC is still tracking COVID-19 hospitalizations, though these data are more delayed and less comprehensive following the PHE’s end.

- Death reporting is also more delayed and less comprehensive.

- The CDC is using networks of testing labs and healthcare centers (like the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System) to estimate COVID-19 trends, similar to its strategies for tracking flu and RSV.

- To track variants, the CDC is relying on a mix of continued PCR samples, wastewater testing, and travel surveillance.

- Vaccinations are no longer reported directly to the CDC, leading the agency to track the 2023-24 vaccines through other means.

In short, we lost a few of the primary data sources that people have used to follow COVID-19 over the last three years. But there’s still a lot of data available, primarily from wastewater surveillance, the CDC’s sentinel networks, and local health agencies.

Here are my tips for tracking COVID-19 this winter.

Look at multiple sources for your community.

Following COVID-19 in your city or state used to be easy: you could just look at case numbers. Now, with that metric unavailable in many places, I would recommend having two or three go-to data sources that you check in tandem. Don’t be certain about a trend (like a new surge) until you’ve seen it in multiple sources at once. These sources might be local wastewater pages, local health department pages, and regional trends from the CDC.

For example, when I want to check on COVID-19 spread in New York City (where I live), I look at:

- The New York State wastewater dashboard, which reports data for NYC as well as surrounding sewersheds (which are helpful to check because NYC’s wastewater data are often reported with delays);

- New York City’s health department’s COVID-19 dashboard, which still reports cases, hospitalizations, and deaths for the city (though I acknowledge these numbers are likely undercounts);

- The CDC’s data for HHS Health Region 2, which covers New York and New Jersey.

Wastewater is the best early indicator.

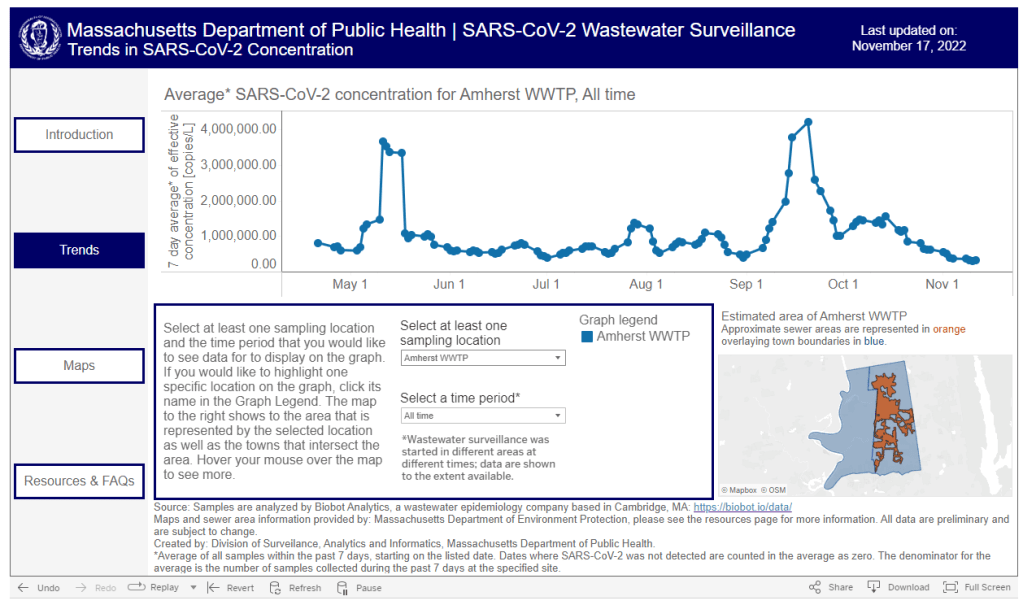

It’s pretty universally acknowledged among epidemiologists and public health experts at this point in the pandemic that, without case data, wastewater surveillance is now our best way to spot new changes in COVID-19 spread. When a new surge occurs, coronavirus levels in wastewater tend to go up days or weeks before other metrics, like hospitalizations.

So, as you track COVID-19 for your community, I would highly recommend that one of your top sources is a wastewater surveillance dashboard.

- Check the CDC’s dashboard, Biobot’s dashboard, and WastewaterSCAN’s dashboard to see if these programs include testing sites near you.

- While these three dashboards are the most popular, you might also be able to find a more localized dashboard produced by your state or local health department. I keep a list of those dashboards on the COVID-19 Data Dispatch website, recently updated for November 2023.

- In addition to local health dashboards, you might find an academic project near you that’s monitoring wastewater. Check the COVIDPoops19 dashboard for a more comprehensive repository of wastewater surveillance projects.

Test positivity is still helpful for trends.

Test positivity—the rate of COVID-19 tests that returned positive results—was a popular indicator early in the pandemic, with policy decisions like whether students could attend school in-person tied to this metric. While test positivity numbers are less available now, people are still getting tested for COVID-19: these tests mostly occur in healthcare settings among people who present with COVID-like symptoms or had recent exposures to the virus.

I still find test positivity to be a helpful metric for watching trends in COVID-19 spread. When the positivity rate goes up, more people are getting COVID-19; and when the rate goes over 10%, that’s a decent indicator that the disease is spreading in significant magnitudes.

Two places to find test positivity data:

- The CDC’s COVID-19 trends page provides positivity data for the U.S. as a whole and HHS regions, based on one of the agency’s respiratory virus surveillance networks;

- Walgreens’ COVID-19 dashboard, which reports positivity results from tests conducted at the pharmacy chain.

Acknowledge data delays, especially around holidays.

Many COVID-19 dashboards used to update on a daily basis. Now, we get weekly updates from most health agencies—and even less frequency in some places. With these update schedules, all data are inevitably delayed by at least a few days. So, when you look at a dashboard, it’s important to keep the update schedule in mind and ask yourself how a trend might have continued following the most recent data available.

Data delays become particularly prominent after holidays: remember, public health officials take days off just like the rest of us. Holiday reporting delays often lead to appearances of low COVID-19 during the immediate week of a holiday, followed by appearances of higher COVID-19 in the weeks after as cases (and other metrics) are retroactively reported. The weeks around Christmas and New Year’s are particularly bad, as most people take both of those holidays off.

Compare current trends to past surges and lulls.

With interpreting COVID-19 data, context is everything. Spread of the virus is usually either rising or falling; comparing current numbers to historical data can help you understand the magnitude of those recent patterns. Is your community seeing as much COVID-19 as it has at past times commonly recognized as surges? Or are you in more of a lull between waves?

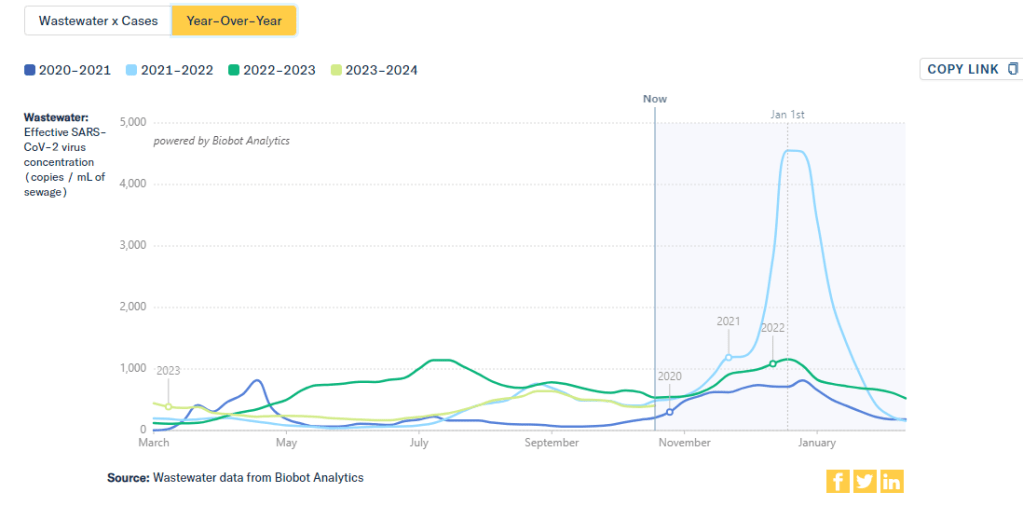

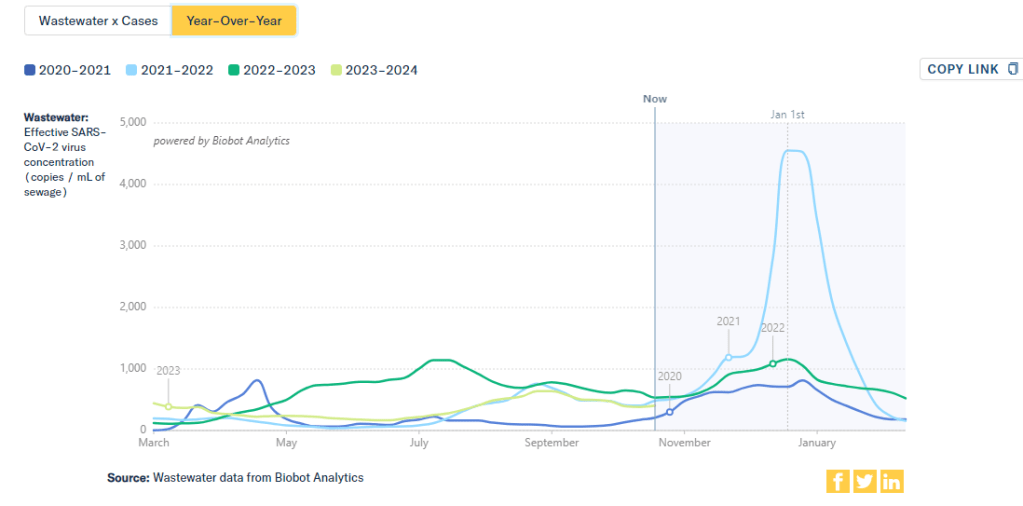

One helpful tool that I often use for such context is a chart on Biobot’s COVID-19 dashboard that provides year-over-year comparisons between coronavirus levels in wastewater in the U.S. Right now, for example, you can see that current viral levels have followed a similar trendline to what we observed in the fall 2021 Delta surge (before Omicron appeared), but lower than this time last year (when different BA variants were spreading quickly).

The original Omicron surge in winter 2021-22 is often a popular point for these comparisons, as pundits love to assure us that a new variant won’t cause as intense a wave as we saw with Omicron’s first appearance. While this can be reassuring, I think it’s important to not just look at the highest peaks for comparison. The summer/fall of Delta in 2021 wasn’t a great time either, and we’re on track to repeat it right now even if no wildly competitive new variants appear.

Keep an eye on variants.

As we watch for a likely COVID-19 surge this winter, viral variants could have an impact on how much the virus is able to spread during our holiday travel and gatherings. You can keep an eye on variant development through a couple of CDC data pages:

- The CDC’s variant proportions, which estimate levels of different variants based on PCR testing;

- Variant patterns from wastewater, which the CDC and local health departments track from select sewage testing sites (many state and local wastewater dashboards include these data as well);

- Travel-based genomic surveillance, a CDC program in which international travelers can opt into PCR testing as they return to U.S. airports, contributing to the agency’s understanding of variants circulating globally.

If you have further data tracking questions or suggestions, please reach out via email or in the comments below.