The sources listed here are included in my source list, along with all featured sources from past issues.

- Detailed hospitalization data go unreported: A new story by NPR’s Pien Huang and Selena Simmons-Duffin reveals county-, city-, and individual hospital-level reports which the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) circulates internally but does not post publicly. HHS’s public reports on hospital capacity only include data at the state level. According to Huang and Simmons-Duffin’s reporting, more local data and contextual information such as per capita calculations and time series would be incredibly useful for the public health experts who are trying to determine where aid is most needed. The NPR story also notes that hospital compliance is low: only 62% of U.S. hospitals had sent HHS all the required information in the week prior to October 30.

- HHS Protect has expanded: For a few months now, the HHS Protect Public Data Hub has only hosted COVID-19 hospitalization data. But recently, the website expanded to include a section on national testing. Users can clearly see cumulative PCR testing numbers from the country, download the full dataset, and read documentation. This dataset has been publicly available on healthdata.gov since July, but through hosting it on the HHS Protect Public Data Hub, the agency has made it more easily accessible for Americans who are not data nerds like myself.

- Daily testing needs: A new tool from the Brown School of Public Health helps users calculate how many tests are needed for key essential groups, both for the nation overall and state-by-state. The tool is intended for public health leaders and policymakers who are starting to scale up as antigen tests become more widely available. For example, New York would need 37,300 tests a day to screen all college and university students.

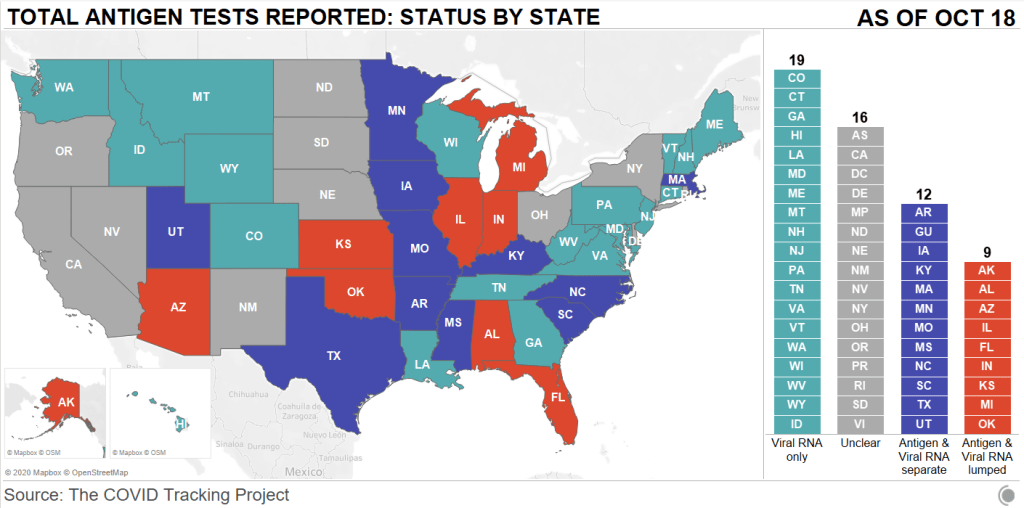

- Pennsylvania’s antigen tests: On October 14, Pennsylvania started distributing antigen test kits to health centers, nursing homes, and other facilities throughout the state. The facilities receiving tests are reported by the state in weekly lists. I wanted to share this because it’s a great example of testing transparency; though if Pennsylvania adds antigen tests to their dashboard, their reporting will be even more comprehensive. For more information on why state antigen test reporting is important—and how states have failed at it so far—see my COVID Tracking Project blog post from last week.

- COVID holiday FAQs: Epidemiologists from Boston University, the University of Alabama, Birmingham, and the University of Miami have compiled their responses to common concerns around the holiday season. The questions included range from, “How do I talk to friends and family members about COVID and the holidays?” to, “Is it important to get my flu shot?” (P.S. It is. Get your flu shot.)

- COVID-19 in ICE detention centers: Since March 24, researchers from the Vera Institute of Justice have been compiling data from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) on COVID-19 cases and testing in immigrant detention centers. The researchers note that ICE replaces previously reported numbers whenever its dataset is updated, making it difficult to track COVID-19 in these facilities over time.

- Eviction Lab: Researchers fromPrinceton University compile data for this source by reviewing formal eviction records in 48 states and the District of Columbia. Although the source’s most recent state-level dataset is as of 2016, the group is also tracking COVID-19-related evictions in real time for a select group of cities. Houston, TX, at the top of the list, has seen over 13,000 new eviction filings since March.

- HHS celebrity tracker: Here’s one more piece of HHS news, this one more lighthearted. This week, POLITICO’s Dan Diamond released an HHS document called the “PSA Celebrity Tracker,” which health officials were using to determine which of America’s favorite people may be useful in an ad campaign encouraging the nation to be less negative about COVID-19. (Here’s more context from POLITICO on the tracker.) Alec Baldwin, for example, is listed as a celebrity who appeals to the elderly, with the additional note: “interested but having a baby in a few weeks.” Lin-Manuel Miranda is listed as appealing to Asian-Americans, with the note: “No information regarding political affiliation.”