It takes three to four weeks for data on a variant COVID-19 case to be made public. I have been quietly stressing out about this fact for about a month, since I learned it from Will Lee, VP of science at the genomics company Helix.

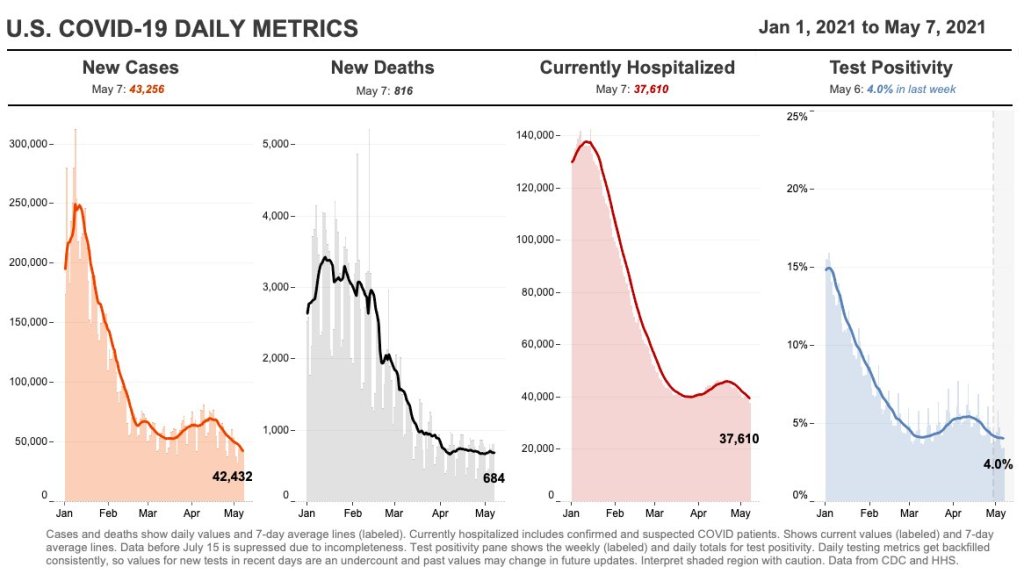

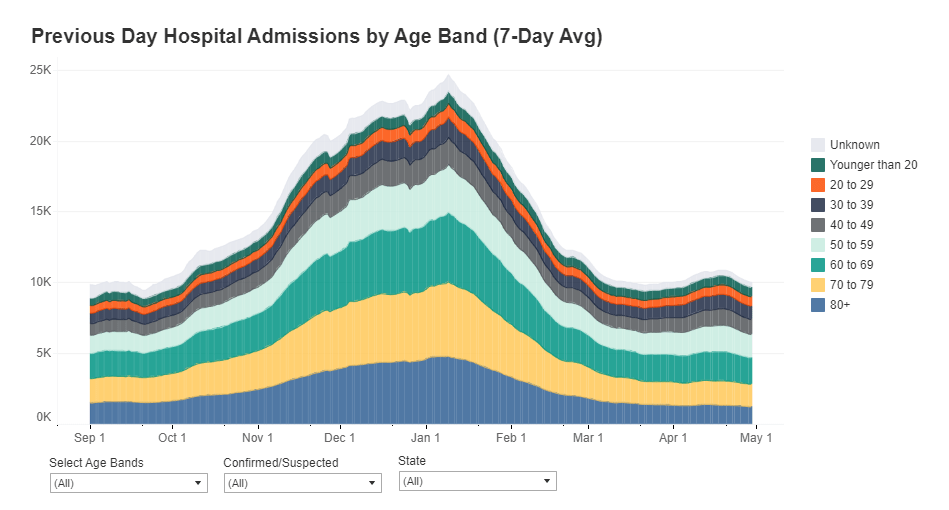

I talked to Lee for a recent Science News piece on the drivers and demographic patterns of the U.S.’s April rise in COVID-19 cases. During our conversation, he shared many details of Helix’s coronavirus sequencing process; most of this information was too technical for me to include in my Science News story, but in the COVID-19 Data Dispatch, I can get as technical as I want.

Here’s an excerpt from our interview, following my question: What is the turnaround time for sequencing? How does it compare to getting a PCR test result?

It is much, much slower. The median time from collection to [PCR] results, it’s varied quite a bit over time, but I think right now, for many labs, it’s less than 48 hours. And so what we do is, after the test result is done—we’re only picking from positive tests, obviously, for sequencing—so we would select the sample, probably somewhere on the order of two to three days after the sample is collected, after the test result is reported. From then, I’d say there’s probably seven to ten days before the sequencing result is available…

What happens is, we do the [PCR] test result, we send it out for sequencing. The turnaround time for sequencing—I’d say in a good case, it’s in the seven to eight day timeframe, sometimes it’s longer than that. There’s an additional holdback on the data before we make it publicly available, because the CDC wants to make sure that public health agencies have time to act on the information first, if it turns out [the case is] someone in their jurisdiction who’s identified to have a variant of concern. That’s potentially another week, depending on how fast they [the local public health agency] act.

And then there’s additionally a lag for when you submit to somewhere like GISAID, and however long it takes them to do their review process and publish it. You add it all together, and you end up with something like 3-4 weeks [from test sample collection to sequence publication].

So, let’s recap. Here’s what it takes to sequence and report a coronavirus variant case:

- PCR test: 1-2 days

- The testing company selects the positive test sample for sequencing: 1-2 days

- Genomic sequencing takes place: 7-10 days

- Local public health department gets notified, uses the sequencing results for contact tracing: Up to one week

- Sequence is submitted to a public repository: Possibly another 1-2 weeks

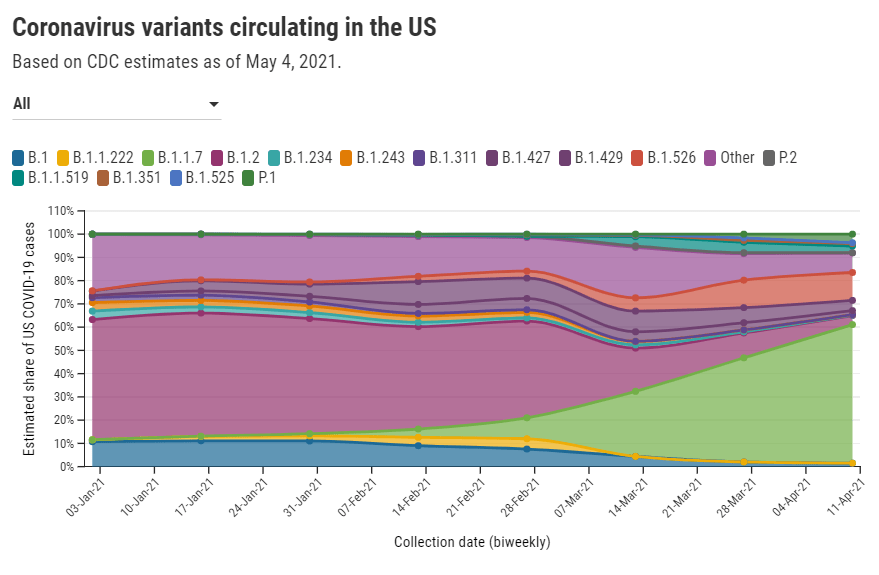

When you add all this up, it’s no surprise that the most recent variant data on the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker are as of April 10, almost four weeks ago. I’m focusing on this process today because I believe the data lag is worth emphasizing. When you see a news report about B.1.1.7 or another variant, remember that the data took several weeks to get from test sample to newspaper.

In other words, when the CDC tells us that B.1.1.7 now makes up about 60% of new cases in the U.S., remember that this number is a snapshot from a month ago. The true number as of today, May 9, is likely far higher.

My interview with Will Lee inspired me to look at lag times for other common variant data sources. Let’s compare:

- CDC’s Variant Proportions page, data from the national genomic surveillance program: Lag of 2-4 weeks, depending on how far away one is from an update when checking the page. (The CDC updates this page every two weeks.)

- Helix’s Surveillance Dashboard, data from the company’s testing sites: Lag of 3-4 weeks. As of May 8, Helix is reporting B.1.1.7 sequence data as of April 15 and SGTF data as of late April. (SGTF, or S gene target failure, is a coronavirus mutation which usually indicates that a case is B.1.1.7-caused.)

- Nextstrain dashboard, data from GISAID: Lag of 1-2 weeks. When I looked at Nextstrain’s coronavirus page yesterday, the most recent available sample sequences were collected on May 1 and the global variant frequencies chart ended at April 27.

- CoVariants dashboard, data from Nextstrain/GISAID: Lag of 2-4 weeks, depending on the country. As of May 8, CoVariants reports data from the week of April 19 for some countries with more robust sequencing programs (U.S., U.K., etc.) and data from the week of April 5 for others.

Nextstrain and CoVariants, both of which are powered by the public sequence repository GISAID, have more recent data than the CDC—likely because academic labs can submit sequences to GISAID without waiting on public health departments. Helix has a lag similar to the CDC’s because its partnerships require the company to submit sequences to public health departments before releasing the information publicly. Some state public health departments report variant data of their own, but this is often done in press releases rather than regular dashboard updates.

Now, bearing in mind that the variant data are all weeks old, what are the most recent variant numbers for the U.S.? And why should we be worried about these variants?

Here’s a status check on the major variants I’m watching:

- B.1.1.7 (first identified in the U.K.): Causing about 60% of cases nationwide as of April 10. Among the states where the CDC reports variant data, it’s most prevalent in Tennessee (74%), Michigan (71%), Minnesota (68%), Georgia (65%), and Florida (63%). This variant is concerning because it spreads a lot more easily than older coronavirus variants; estimates range from 40% to 70% more transmissible.

- B.1.526 (first identified in New York City): Causing about 12% of cases nationwide as of April 10. This variant is also likely more transmissible, but a recent CDC report suggests that it does not lead to more severe disease or increased risk for vaccine breakthrough cases. B.1.526 has yet to be classified nationally as a variant of concern, so the CDC isn’t publishing state-by-state data for it. (But if you live in NYC, check out this Gothamist article for ZIP code-level prevalence data.)

- B.1.427/B.1.429 (first identified in California): Causing about 6% of cases nationwide as of April 10. I suspect the pair may be getting outcompeted by B.1.1.7, as it was representing closer to 10% of cases in a previous CDC reporting period—it’s more transmissible than the wildtype coronavirus, but not as transmissible as B.1.1.7 . This variant pair is most prevalent in California (38%), Arizona (28%), and Colorado (24%).

- P.1 (first identified in Brazil): Causing about 4% of cases nationwide as of April 10. This variant has been tied to surges in Brazil and other South American countries; it’s more transmissible, associated with a higher death rate, and can reinfect patients who already recovered from COVID-19. While it currently represents a fairly small share of U.S. cases, computational biologist Trevor Bedford recently pointed out that P.1. “has been undergoing more rapid logistic growth in frequency” compared to other variants.

- B.1.351 (first identified in South Africa): Causing about 1% of cases nationwide as of April 10. Soon after it was identified last December, the COVID-19 vaccines were shown to be less effective against this variant. But “less effective,” for the mRNA vaccines, is still pretty damn effective, as this recent study from Qatar demonstrates.

- B.1.617 (first identified in India): Not yet represented in CDC data, but it’s been identified in several U.S. states over the course of April and May. This variant is strongly tied to India’s recent surge. While you may see it called a “double variant” because it has mutations at two key coding sequences, B.1.617 doesn’t actually have double the transmission bump or double the severity of older coronavirus variants, as explained here by epidemiologist Katelyn Jetelina.

It’s also worth emphasizing that genomic sequencing is still not conducted evenly across the country. The CDC releases state-by-state variant prevalence data for states which have submitted more than 300 coronavirus sequences in a four-week period. As of April 10, only half of the states have met this benchmark; many states in the Midwest and South still aren’t represented in the CDC’s data.

I am considering adding a variant data annotations page to the CDD website, in order to more consistently keep track of all the different info sources on these lineages. Would you use this page? What information would you like to see there? Shoot me an email (betsy@coviddatadispatch.com) or leave a comment here on the website to let me know.