This week, I had a new story published at the data journalism site FiveThirtyEight. The story explores the U.S.’s failure to comprehensively track breakthrough cases, and how that failure has led officials to look towards data from other countries with better tracking systems (eg. Israel and the U.K.) as they make decisions about booster shots.

In the piece, I argue that a lack of data on which Americans are most at risk of breakthrough cases—and therefore most in need of booster shots—has contributed to the confusion surrounding these additional doses. Frequent COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers might recognize that argument from this CDD post, published at the end of September.

Of course, an article for FiveThirtyEight is able to go further than a blog post. For this article, I expanded upon my own understanding of the U.S.’s public health data disadvantages by talking to experts from different parts of the COVID-19 data ecosystem.

At the CDD today, I’d like to share one of those interviews. I spoke to Zoe McLaren, a health economist at the University of Maryland Baltimore County, about how the U.S. public health data system compares to other countries, as well as how data (or the lack of data) contribute to health policies. If you have been confused about your booster shot eligibility, I highly recommend giving the whole interview a read. The interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Betsy Ladyzhets: I’m writing about this question of vaccine effectiveness data and breakthrough case data in the U.S., and how our data systems and sort-of by extension public health systems compare to other countries. So, I wanted to start by asking you, what is your view of the state of this data topic in the U.S.? Do you think we can answer key questions? Or what information might we be missing?

Zoe McLaren: It’s the age-old problem of data sources. A lot of cases are not going to be reported at all. And then even the ones that are reported may not be connected to demographic data, for example, or even whether the people are vaccinated or not. Whereas other countries like Israel, and the U.K., your positive COVID test goes into your electronic health record that also has all the other information.

And Medicare patients, they have that whole [records] system. There will be information [in the system] about whether they got vaccinated, as well as whether they have a positive test. So that data will be in there. But for other people, it may or may not be in an electronic health record. And then of course, there’s multiple different electronic health record systems that can’t be integrated easily. So you don’t get the full picture.

But it’s all about sample selection. Not everyone [who actually has COVID] is ending up in the data, which messes up both your numerator and denominator when you’re looking at rates.

BL: Could you say more about how our system in the U.S. is different from places like Israel and the U.K., where they have that kind of national health record system?

ZM: When the government is providing health insurance, then all of your records and the [medical] payments that happen, there’s a record of them… And then, because it’s a national system, it’s already harmonized, and everyone’s in the same system. So it’s really easy to pull a dataset out of that and analyze it.

Whereas in the US, everything is incredibly fragmented. The data, and the systems and everything is very fragmented. The electronic health systems don’t merge together easily at all. And so you get a very fragmented view of what’s going on in the country.

BL: Right, that makes sense. Yesterday, I was talking to a researcher at the New York State Health Department who did a study where they matched up the New York State vaccination records with testing records and hospitalization records, and were able to do an analysis of vaccine effectiveness. And he said, basically, the more specific, you tried to go with an analysis, the harder it is to match up the records correctly, and that kind of thing.

ZM: Exactly. It’s easy to match on things like age, sex, race, since everybody has them. But then, the different data fields are gonna have different formats and be much harder to merge together.

BL: So what can we do to improve this? I know Medicare for All is one option—

ZM: Medicare for All, end of story, end of article. It would solve so many problems.

It’s tricky, though, because there isn’t a simple fix. All of these health systems have their own electronic health records, and integrating them is really costly and hard to do, and who is going to pay for that? There’s also additional privacy concerns about integrating things, in terms of protecting privacy and confidentiality. So, that’s really tricky.

The way that we get around that, in general, is to have reporting requirements. Like with COVID tests, [providers are] required to report to the CDC or the HHS… Still, that’s also costly and time consuming. But that is kind-of the best thing that we can do right now, is have the different [public health] entities produce reports on a regular basis and send that to a centralized location. And the reports are supposed to be produced in a way that they are harmonized, they’re easy to put together from all the different systems.

The problem with the different systems not integrating is, it requires everyone to basically fill out the equivalent of a form and send it in—listing individual patient information, or at the state level, individual county information. An example of that is the COVID data. All of the COVID data gets reported up to the national level [by state and county health departments]…

But the reporting often gives you the numerators, when you need to figure out the denominators. Because you would want to know, for example, we want to know what proportion of breakthrough cases end up hospitalized. But if only the hospitalized people end up in the data, and a lot of breakthrough cases go either undetected or never tested, or they do an at-home test and there’s no record of that positive case in the system, then your denominator is—there’s a problem with your denominator. That’s a problem with sample selection, you get people that are self-selecting into the numerator [by testing positive], but also self-selecting into the denominator [by getting a test to begin with].

BL: Yeah, that makes sense. I know you said it would be pretty complicated to basically force different public health departments—to standardize them so that they’re all reporting in the same way. Is there more that researchers in the US could be doing in the short-term to either improve data collection or use what we have to answer questions like, what occupations might confer higher risk of a breakthrough case?

ZM: This is a coordination problem. Because in general, we all have an incentive to contribute to having a better understanding of breakthrough cases. But the trick is that, unless the national government or the CDC takes the role of saying what the [data] format’s gonna look like…

Part of the problem is that there’s an effort involved [in collecting these data] and people don’t want to put in the effort. But if they do want to put in the effort, then you still have a coordination problem, because who gonna to be deciding what format we’re using?

BL: Or like, what the data definitions are.

ZM: Exactly. Like, do you report the month and the day of the vaccination dose, or just the month of the dose? Things like that where it doesn’t seem like a big deal, but it does matter for research purposes. If you look, for example, at the Census, or any of the national surveys, like the Current Population Survey or the National Labor Force Survey where we get unemployment numbers, there are big committees that figure out which questions we’re asking and how we ask them. So, if the CDC just says, like, “This is the dataset we’re building,” then everyone [local agencies] will be like, “Okay, we’re gonna send our reports in that way.”

Part of [the challenge] is that it takes effort to produce the data, and part of it is somebody needs to coordinate. And usually that would be something the CDC would do, saying, “This is the data that needs to be reported to us,” and everybody reports to them. But they could be doing more, they could be asking for more detailed information—for example, data based on vaccination status, because that information will be important for understanding the progression of the pandemic.

BL: Yeah. I volunteered for the COVID Tracking Project for a while, and one of the most tedious things that we had to do there was figuring out different definitions for like, what states were considering a case or a test, or whatever else. So that definitely makes sense to me.

ZM: Exactly. And the COVID Tracking Project filled a gap. Nobody was doing that [collecting data from the states], so the COVID Tracking Project did that… But it’s tricky, because a lot of the stuff that seems like splitting hairs [on definitions] really does make a difference when you’re doing your analysis.

BL: I also wanted to ask you about what the implications are of this lack of standardized data in the U.S., and the lack of information that we have—largely around vaccinations, but I think there are other areas as well where we’re missing information. So I’m trying to figure out, for this story, how data gaps might contribute to the confusion that people feel when they watch health agencies make decisions. Like watching all the back and forth on booster shots, or thinking about Long COVID, other things like that.

ZM: Well, we talk about evidence-based medicine, and we also care about evidence-based policy. And so it means that when the quality of data is poor, the quality of our policy is going to be worse. So it really is in everybody’s best interest to have high-quality data, because that is the bedrock of producing high quality policy.

BL: Right. So if we don’t know, for example, if people who live and work in certain situations are more likely to have a breakthrough case, then we can’t necessarily tell them—we can’t necessarily say, “These specific occupations should go get booster shots.” And then we just say, “Everyone can go get a booster shot.”

ZM: It means that we’re flying blind. And the problem of flying blind is twofold. One is that you can end up making poor decisions, the wrong decisions, because you don’t have the data. And then the other problem is that you end up making decisions that, in economics, we call it “inefficient.” I think about [these decisions] as, you end up with “one size fits all.”

If we have really high quality data, then we’re able to create different policies for different types of people, and that helps minimize any of the downsides. But the less data we have, the more we have to rely on “one size fits all.” And of course, if “one size fits all,” it’s going to be too much for some people and too little for others. Data would help improve that.

BL: How do you think that this kind of “one size fits all” contributes to how individual people might be confused or might not be sure how to kind of interpret the policies for their own situations?

ZM: I think in a “one size fits all,” people get very frustrated because they see in their own lives, both the uncertainty and how that can be stressful—and also the waste. The situations where they fall under one policy, but they have enough information to know that that policy doesn’t necessarily apply to them. It does undermine confidence in policymaking. People get frustrated with “one size fits all,” because it seems wasteful.

Though sometimes the “one size fits all” is still optimal, it’s better than the alternative. For example, the recommendation of “one size fits all” wearing masks tends to trump the “one size fits all” of not wearing masks. But there’s waste. There are situations where we end up wearing masks where they wouldn’t necessarily be needed. And vice versa.

BL: Yeah. That makes me think of friends I have who are eligible to get booster shots because of medical conditions, but they’re sort-of thinking, “I wish the shots could go to another country where they need vaccinations more.” And that’s not something individuals have any control over, but it’s frustrating.

ZM: Part of it is, with the booster shots, is the guidelines that say people who have higher occupational exposure to risk [are eligible] without specifying exactly who that is. That is one way that we allow some leeway. So it’s not a “one size fits all” where nobody gets it, because there’s actually people who qualify under higher occupational exposure. But we also don’t want to have a “one size fits all” where we tell everyone they need it, because we do want to be sending doses abroad as well.

So that’s a situation where we know that a “one size fits all” is not perfect. And so we create a, like, “use your judgement, talk to your doctor” kind-of thing that tries to help people self-select into the right groups… There are likely a lot of people who do have higher exposure and should be getting it, but don’t think the benefit applies to them.

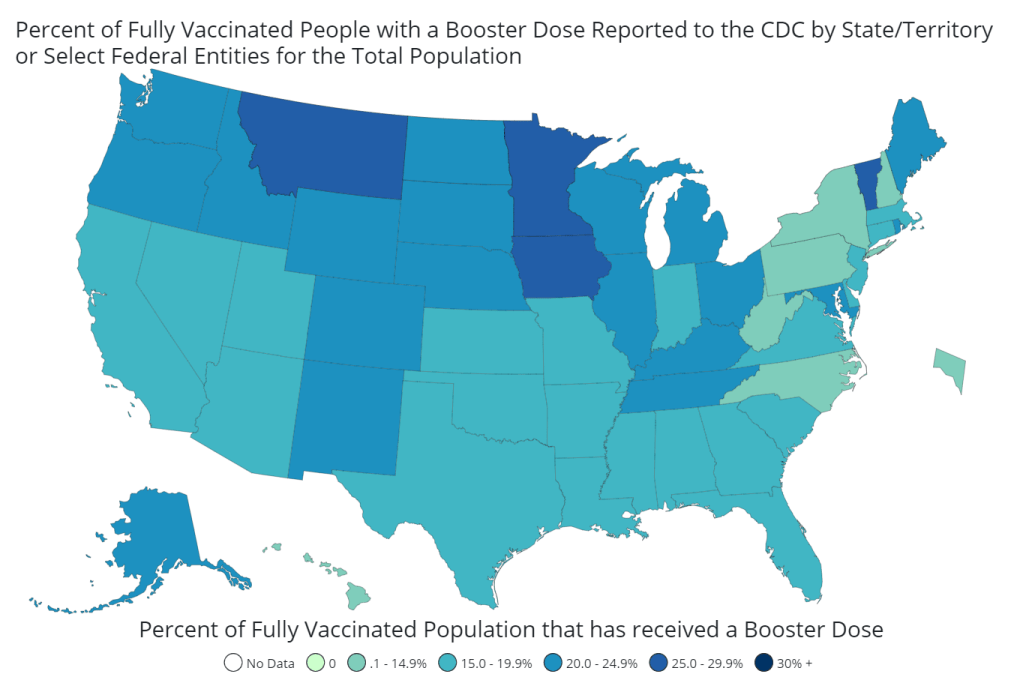

Editor’s note: According to one analysis, about 89% of U.S. adults will qualify for a booster shot after enough time has passed from their primary vaccine series. And, according to the October COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor report, four in ten vaccinated adults were unsure whether they qualified.

BL: I also wanted to ask, you mentioned rapid tests—those don’t necessarily get reported. Are there other other things that you think pose data gaps in the U.S. public health system?

ZM: With rapid tests, the actual tests are not getting reported. But the important thing is, people are getting tested. I mean, the reason we want good data quality is to reduce cases, and we wouldn’t want to limit access to rapid tests in order to collect data, because it’s much easier to prevent the cases by allowing people to get tested in their homes.

But yeah, just the fact that there’s no centralized database for analysis [is a gap]. I mean, if you look at the U.K., and Israel, they have these great studies, because they’re able to just download, like, the entire population into a dataset. And it has all the information they need, like demographic factors. The fact that the U.S. has made so much of its national policy based on Israeli data, this shows how far behind we are with having our own data to answer these questions.

BL: Yeah. I know, it’s something like half or a third of cases in the U.S., the CDC doesn’t have race and ethnicity information for [editor’s note: it’s 35%], and other stuff like that. It’s wild.

ZM: Yeah… And one of the things about reporting is that every additional piece of data you want is very costly. And so you have to be very judicious about [collecting new values].

BL: Well, those were all my questions. Is there anything I didn’t ask you that you think would be important for me to know for this story?

ZM: Just that data is helpful for planning now, and helpful for the future. If we can improve our data systems now—it’s part of being prepared for the next pandemic.

More vaccine reporting