I had two new articles about Long COVID published this week:

- This story in Science News describes how researchers are working to fill gaps in Long COVID data, largely by collaborating with patients and across different areas of medicine.

- This story in Gothamist/WNYC describes three public Long COVID clinics run by New York City Health + Hospitals, which offer a range of care to New Yorkers with the condition but fall short of all the specialties needed for comprehensive treatment.

The reporting process for both stories gave me a lot to think about, in considering potential improvements in recording who has Long COVID and how this chronic disease impacts people.

And we have a lot of room for improvement. There are plenty of reasons why Long COVID research and data collection are currently difficult, ranging from a lack of consistency in how the condition is diagnosed to historical underfunding for similar chronic diseases like myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and dysautonomia. For more details, see this post I wrote in May.

The U.S. scientific and medical systems also made specific mistakes early in the pandemic that contributed to our current data gaps, including the dearth of PCR testing—leading many current long-haulers to not have positive test results from their initial infections—and early refusals by many doctors to believe patients’ prolonged symptoms had resulted from the coronavirus. Most medical schools do not spend much time training new doctors to recognize complex, chronic diseases, leaving them unprepared to tackle Long COVID.

But these problems can be addressed—especially if doctors and researchers are willing to step outside their specific fields to collaborate with each other and with patients. Here are a few specific recommendations that I learned about in reporting my stories for Science News and Gothamist/WNYC.

Listen to and collaborate with patients.

“Patients know the right questions to ask to properly document their experience,” Lisa McCorkell, one of the founders of the Patient-Led Research Collaborative (PLRC), told me in an email interview for my story.

In fact, a survey study by PLRC in which patient-researchers asked other long-haulers to describe their symptoms is considered one of the most comprehensive accounts of this condition. Other researchers have used this list of symptoms in designing their own patient surveys.

Surveys are one important mechanism of compiling patient experiences, as they can capture information that does not make it into medical records. (Common Long COVID symptoms like post-exertional malaise often are not well-captured in these records.) But patients can also weigh in on other aspects of study methodologies, such as how to collect data in a way that won’t overly tax participants or how to compare groups of patients for accurate results.

Plus, hypotheses from patients can be valuable starting points for clinical trials, as Julia Moore Vogel from the Scripps Research Translational Institute explained to me. Vogel, who is a long-hauler herself, is working on a new study at Scripps that’s informed by her and other patients’ experiences with Garmin wearable devices. The projects funded by PLRC’s grant program offer further examples of research studies informed by patient priorities.

Connect health records from different sources.

One major challenge with studying Long COVID is that this complex condition can impact every organ system in the body. You can’t just analyze heart disease records from a cardiology practice, or lung function records from a pulmonary practice. Every patient could be seeing ten or more different specialists, and all of those doctors might inform different pieces of the overall disease puzzle.

As a result, devising systems that better compile and connect records from different sources is a priority for researchers studying Long COVID. Arjun Venkatesh, a patient-reported outcomes researcher, described this as “the clunkiest part” of his work: there are a lot of “hidden barriers” to connecting records, he said, ranging from privacy protections to technical mismatches. (For example, a patient requesting their records from a particular doctor might be asked to provide a fax number, something most people do not have in 2022.)

Still, new projects are in the works to make this type of data sharing easier. One example is Kindred, an app designed by Yale researchers that empowers patients to request their electronic health records and share them with scientists studying Long COVID. Patients also have more legal protections in making data requests now, thanks to a new federal rule that took effect this fall.

Use wearables and other new tracking technologies.

Smart watches, Fitbits, and other similar trackers are usually advertised for consumers interested in better tracking their individual health and fitness. But they can also provide valuable, long-term data to researchers studying health conditions like Long COVID.

The Scripps Research Translational Institute is one institution focused on wearable devices, through studies like Vogel’s and another program called the DETECT study, led by epidemiologist Jennifer Radin. In DETECT, researchers compile data from people across the country who have volunteered to share their wearable device data with Scripps. After one of the participants gets COVID-19, the scientists can compare their post-COVID health indicators to the patient’s pre-COVID baseline.

“We compare each person to themselves over time,” Radin told me when I talked to her for my Science News story. This method is different from traditional medical research, in which two similar groups of people are compared to each other on a population-wide basis.

Wearables research faces a lot of its own challenges, such as expanding access to more people (by making devices more affordable or even giving them to study participants for free) and creating analysis systems that can make sense of thousands of data points from each patient. But I personally find it fascinating and hope to continue covering this area. I was even inspired by my reporting to buy a smart watch, as a holiday present to myself.

Local surveys and outreach in partnership with community groups.

Anyone can get Long COVID—young or old, vaccinated or unvaccinated, with or without prior health conditions. But a lot of people still don’t know about this chronic condition, even when they might be experiencing long-term symptoms themselves.

As a result, a major priority for Long COVID researchers and patient-advocates is improving education and outreach about this condition. New York City has a program that could serve as an example here: NYC Health + Hospitals runs a hotline called AfterCare, which residents can call to learn about Long COVID and city resources, including the public clinics I wrote about.

While AfterCare has proactively called New Yorkers who previously tested positive for COVID-19, the program’s administrators are concerned that it’s likely not reaching everyone who could be served by the hotline. Local long-haulers who I talked to for my Gothamist/WNYC story want to see broader outreach—like subway ads, billboards, and commercials—telling people about Long COVID.

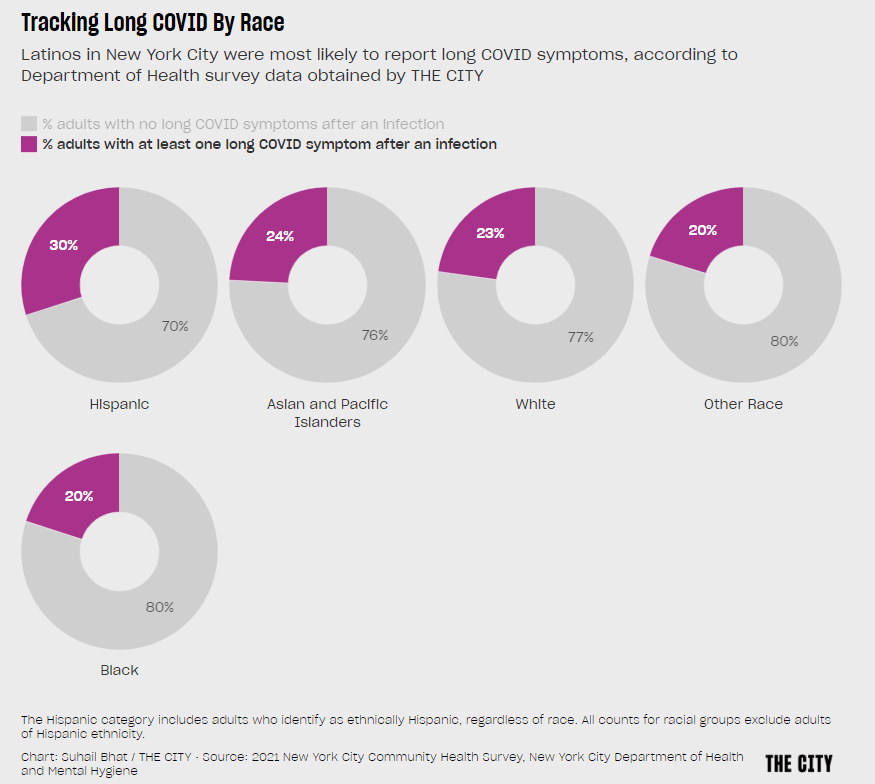

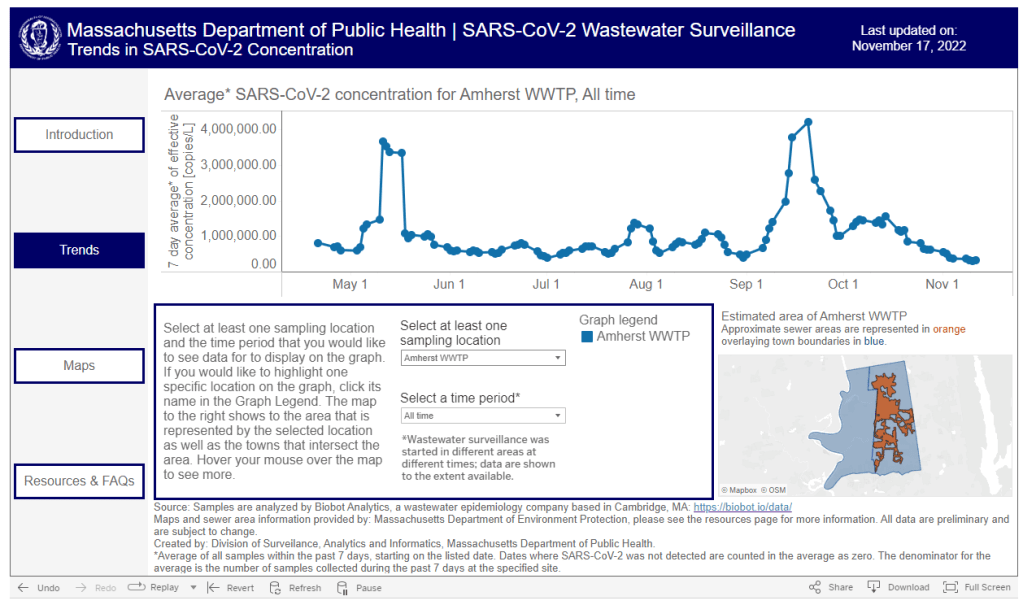

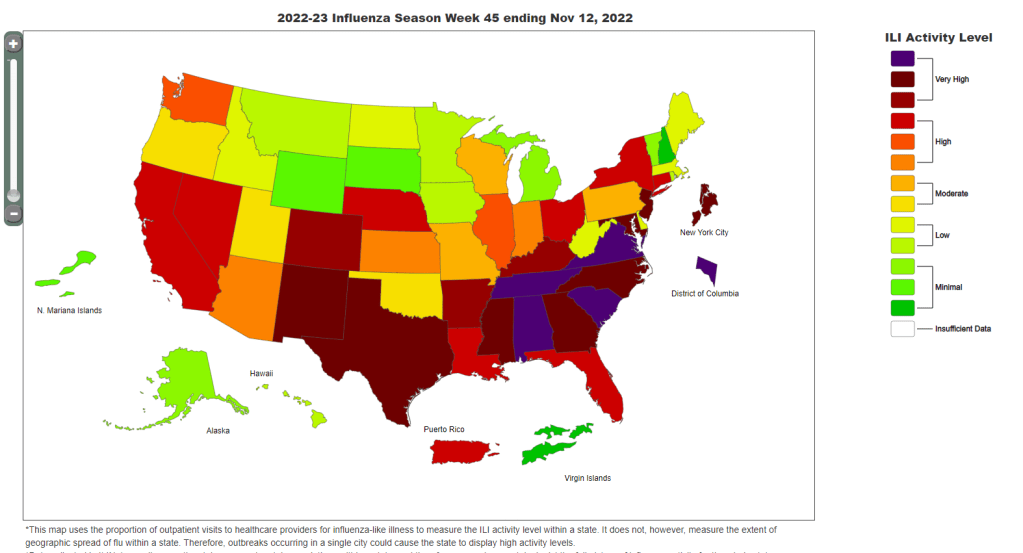

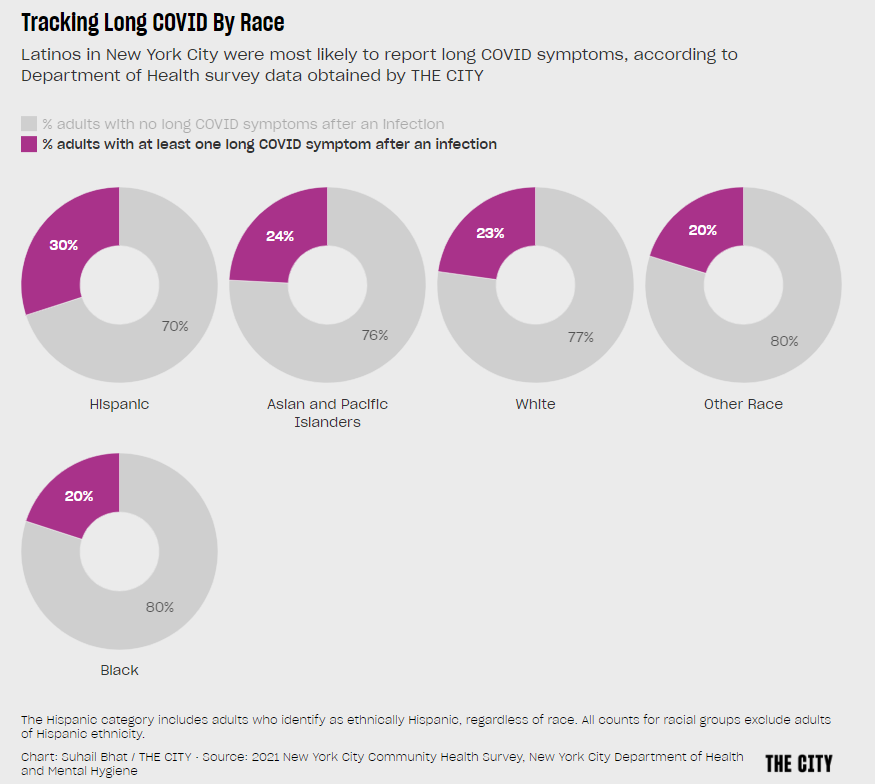

These same outreach programs could also help researchers collect more comprehensive data about Long COVID. Last week, THE CITY, another local NYC outlet, reported on some early results of a survey conducted by the city health department to find out which groups of New Yorkers are most vulnerable to the condition. Unsurprisingly, the survey found that Hispanic/Latino residents and those living in the Bronx were disproportionately impacted.

I hope to see more local health agencies follow in NYC’s lead to conduct surveys like this one, paired with outreach and education about Long COVID. This type of data could go a long way in showing political leaders where more resources are needed.