I wanted to highlight a couple of questions (and comments) that I’ve received recently from readers, hoping that they will be useful for others.

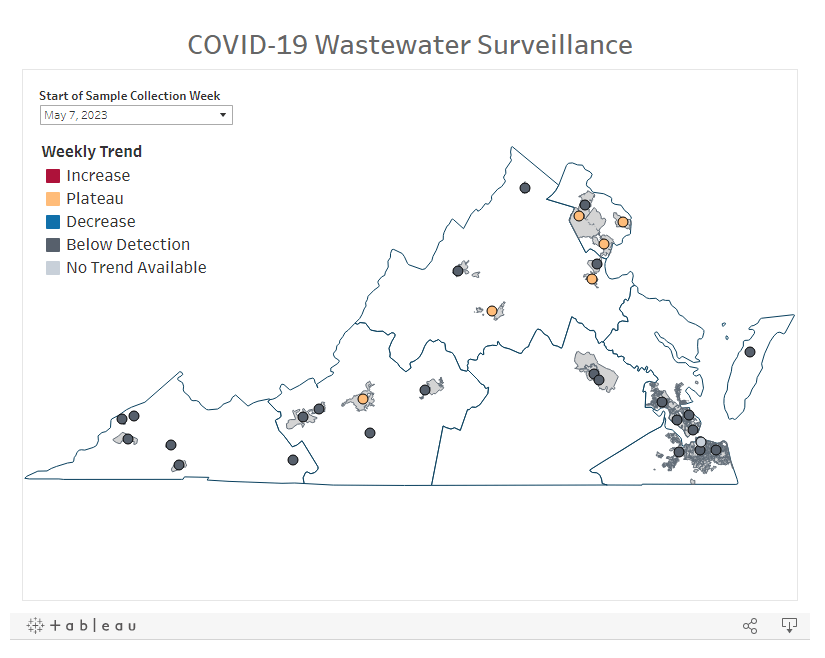

Interpreting wastewater surveillance data

One reader asked about how to interpret wastewater surveillance data, specifically looking at a California county on the WastewaterSCAN dashboard. She noticed that the dashboard includes both line charts (showing coronavirus trends over time) and heat maps (showing coronavirus levels), and asked: “I’m wondering what the difference is, and which is most relevant to following actual infection rates and trends?”

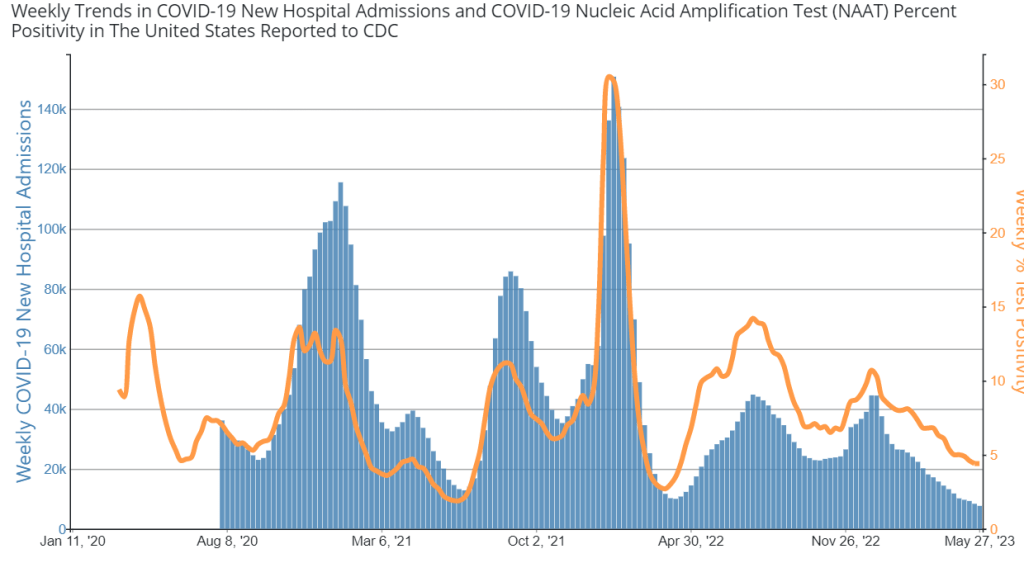

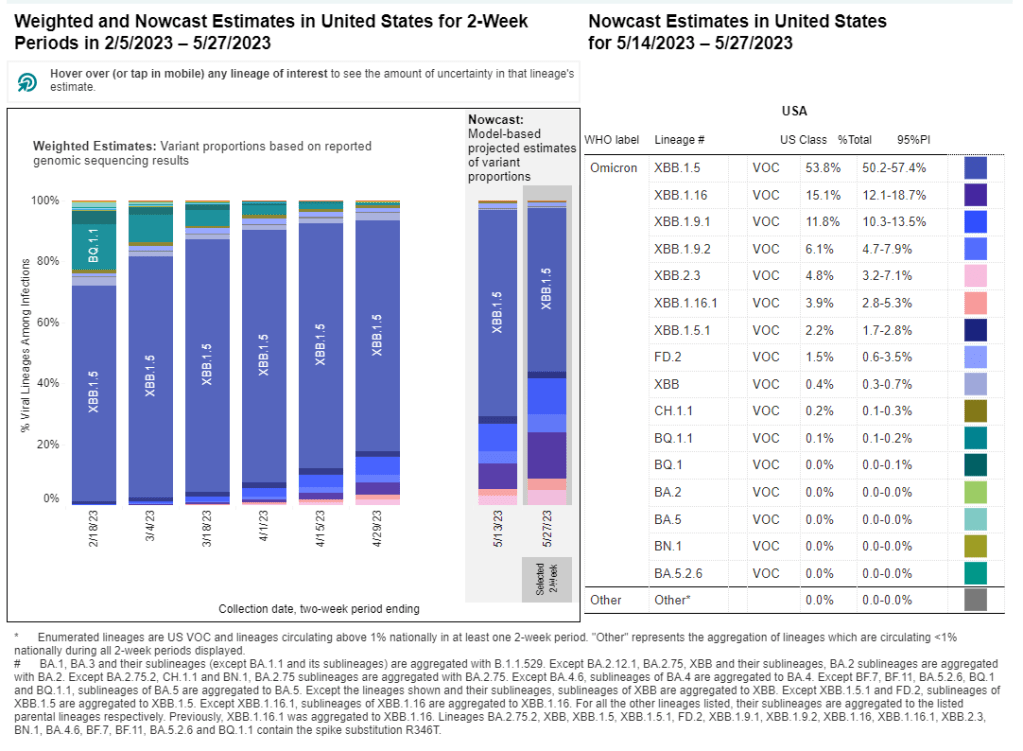

My response: Wastewater data can be messy because environmental factors can interfere with the results, and what may appear to be a trend may quickly change or reverse course (this FiveThirtyEight article I wrote last spring on the topic continues to be relevant). So a lot of dashboards use some kind of “risk level” metric in addition to showing linear trends in order to give users something a bit easier to interpret. See the “virus levels” categories on the CDC dashboard, for instance.

Personally, I like to look at trends over time to see if there might be an uptick in a particular location that I should worry about, but I find the risk level metrics to be more useful for actually following infection rates. Of course, every dashboard has its own process for calculating these levels—and we don’t yet have a good understanding of how wastewater data actually correlate to true community infections—so it’s helpful to also check out other metrics, like hospitalizations in your county.

Rapid test accuracy

Another reader asked: “Is there any data on the effectiveness of rapid tests for current variants like Arcturus? I’m hearing more and more that they are working less and less well as COVID evolves.”

My response: Unfortunately, I’m not aware of any specific data on rapid test effectiveness for recent variants. Early in the Omicron period, there were a few studies that showed the rapid tests still worked for that variant. The virus has obviously evolved a lot since then, but there is less interest in and fewer resources for evaluating these questions at this point in the pandemic, so it’s hard to say whether the continued mutations have had a significant impact on test effectiveness.

I think it’s important to flag, though, that rapid tests have never been highly accurate. People have tested negative on rapids—only to get a positive PCR the next day—since these tests were first introduced in spring 2021. The tests can be helpful for identifying if someone is contagious, with a high viral load, but are less accurate for people without symptoms. So, my recommendation with these tests is always to test multiple times, and to get a PCR if you have access to that. (Acknowledging there is less and less PCR access these days.) Also, if you were recently exposed to COVID-19, wait a few days to start rapid testing; see more details in this post from last year.

Double dose of Paxlovid

Another reader wrote in to share their experience with accessing Paxlovid during a recent COVID-19 case. The reader received a Paxlovid prescription, which led to a serious alleviation of symptoms. But when she experienced a rebound of symptoms after finishing the Paxlovid course, she had a hard time getting a second prescription.

“Fauci, Biden, head of Pfizer and CDC director got a second course of Paxlovid prescribed to them,” the reader wrote. “When I attempted to get this, my doctors pretended I was crazy and said this was never done.” She added that she’d like to publicize the two-course Paxlovid option.

My response: I appreciate this reader sharing her experience, and I hope others can consider getting multiple Paxlovid prescriptions for a COVID-19 case. The FDA just provided full approval to Pfizer for the drug, which should alleviate some bureaucratic hurdles to access. I also know that current clinical trials testing Paxlovid as a potential Long COVID treatment are using a longer course; 15 days rather than five days. The results of those trials may provide some evidence to support a longer course overall.

If you have a COVID-19 question, please send me an email and I’ll respond in a future issue!