- New York Times COVID-19 tracker is back: After shutting down ahead of the ending federal public health emergency, the New York Times COVID-19 tracker has now resumed updates. Since the tracker is based on CDC data, case numbers and other major metrics are no longer available; but readers can find hospital admissions, deaths, and vaccinations nationally and by state, along with some local data based on hospital service areas. The NYT website doesn’t give much information about why they resumed updates—if anyone reading this can share what happened, please let me know! (And thank you to reader Robin Lloyd who flagged the renewed updates.)

- CDC Director calls for more data authority: CDC Director Rochelle Walensky appeared in front of Congress this week, speaking to Republican lawmakers for a hearing about her time leading the agency before she steps down at the end of June. One notable trend from the hearing, according to reporting by Rachel Cohrs at STAT News: Walensky acknowledged that the CDC wasn’t able to collect some key COVID-19 data points, such as vaccination rates for COVID-19 patients in hospitals. Walensky called for Congress to give the CDC more authority in collecting data from state and local health departments.

- CDC expanding its wastewater testing targets: Another CDC update for this week: the agency’s National Wastewater Surveillance System is expanding the pathogens that it will look for in sewage, Genome Web reports. NWSS plans to test for several respiratory viruses (COVID-19, flu, RSV), foodborne infections such as E. coli and norovirus, antimicrobial resistance genes, mpox, and other pathogens that may warrant concern. CDC scientists are working with the company GT Molecular to develop and test new assays. Other wastewater research groups are similarly developing tests to expand the health data that we get from sewage, I’ve learned in reporting for an upcoming story (which will be out later this summer).

- Genomic surveillance to keep tabs on Omicron’s evolution: CDC researchers invovled with tracking coronavirus variants shared some updates in a study published this week by the agency’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. As fewer people are getting PCR tests across the U.S., the CDC has access to fewer samples for sequencing than it did at prior points in the pandemic. As a result, scientists have had to update their analytical procedures for using available data to estimate how much different variants are spreading. According to the CDC, Omicron has dominated the U.S. since early 2022, with earlier BA lineages giving way to XBB.

- Fungal infections increased during the pandemic: In recent years, hospital patients have become increasingly at risk of infection with fungi, which can spread widely in healthcare settings. A new paper from the CDC adds evidence to this trend: fungal infections in hospitals have increased steadily from 2019 through 2021, the researchers found. The researchers also found that patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and a fungal infection had high mortality rates, with almost half of these patients dying in 2020-2021. COVID-19 can disrupt patients’ immune systems and make them more vulnerable to fungi, the researchers suggested. This is a major threat that’s likely to continue in coming years.

Tag: Wastewater

-

Sources and updates, June 18

-

National numbers, June 18

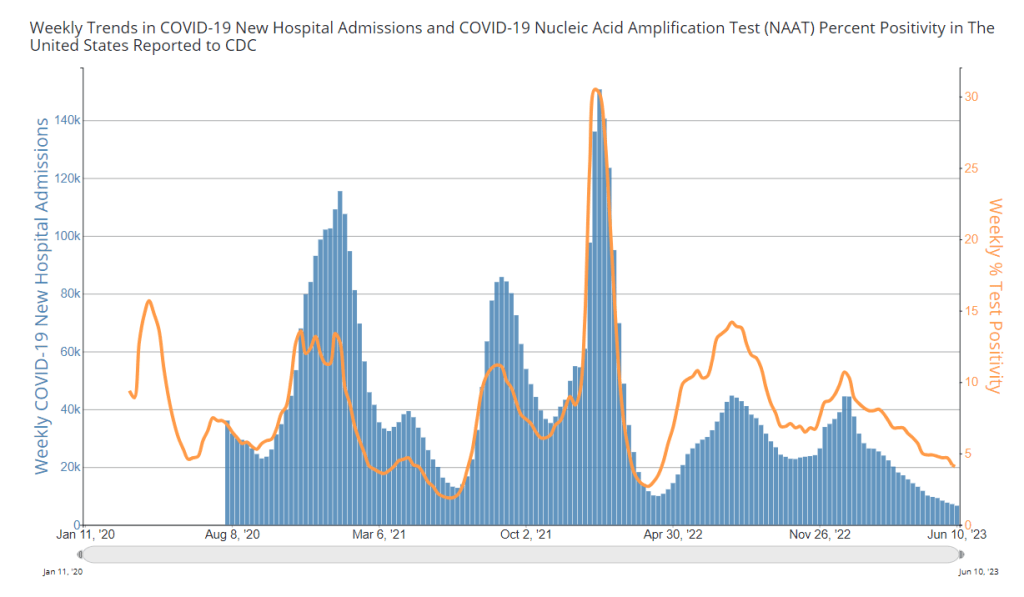

COVID-19 hospital admissions and test positivity (from a select number of labs) are both trending slightly down. Chart from the CDC. In the past week (June 4 through 10), the U.S. reported about 6,600 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 950 new admissions each day

- 2.0 total admissions for every 100,000 Americans

- 8% fewer new admissions than last week (May 28-June 3)

Additionally, the U.S. reported:

- 4.0% of tests in the CDC’s surveillance network came back positive (a 5% decrease from last week)

- A 5% lower concentration of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater than last week (as of June 14, per Biobot’s dashboard)

- 40% of new cases are caused by Omicron XBB.1.5; 26% by XBB.1.16; 21% by XBB.1.9 (as of June 10)

Overall, the national COVID-19 picture remains fairly similar to what we’ve seen for the last few weeks. The U.S. is at a plateau of COVID-19 spread; we could see an increase this summer, but limited data make it hard to say for sure.

New hospitalizations for COVID-19 continue to trend slightly down, with just under 1,000 patients admitted each day nationwide. This is the first time that the U.S. has passed this low benchmark since early in the pandemic, and suggests the protective value of vaccinations and prior infections for preventing severe symptoms.

Biobot Analytics resolved the data issue I mentioned last week and provided updated wastewater numbers, also showing a continued (though slight) downward trend. Current national coronavirus levels are far below this time last year, when Omicron BA.2 variants were spreading widely, though they’re still above prior low points in 2020 and 2021.

Biobot’s regional data also show mostly plateaus, though coronavirus levels may be increasing very slightly in the Northeast. The CDC’s wastewater data also suggest some places in the Northeast may be seeing increased viral spread, but it’s difficult to identify a clear regional trend.

Trends from the CDC’s lab testing network similarly show a potential increase in COVID-19 spread in the Northeast over the last couple of weeks, though this testing trend has yet to translate to higher hospitalizations. In New York City, some of the sewersheds that reported recent coronavirus upticks now appear to be trending back down.

Is a summer surge coming for the Northeast, and then the rest of the country? Right now, it’s quite hard to say; signals from wastewater and testing data are mixed, sometimes delayed, and tough to interpret in the short term. I’ll be watching closely to see how this changes in the coming weeks.

Meanwhile, it’s important to remember that data are especially limited when it comes to Long COVID, one of the most severe (and most likely) impacts of coronavirus infection. As testing becomes less and less accessible, fewer people will recognize their infections—and, as a result, they may be less likely to recognize later symptoms as Long COVID. But those symptoms can still occur, and cause lasting damage.

-

National numbers, June 11

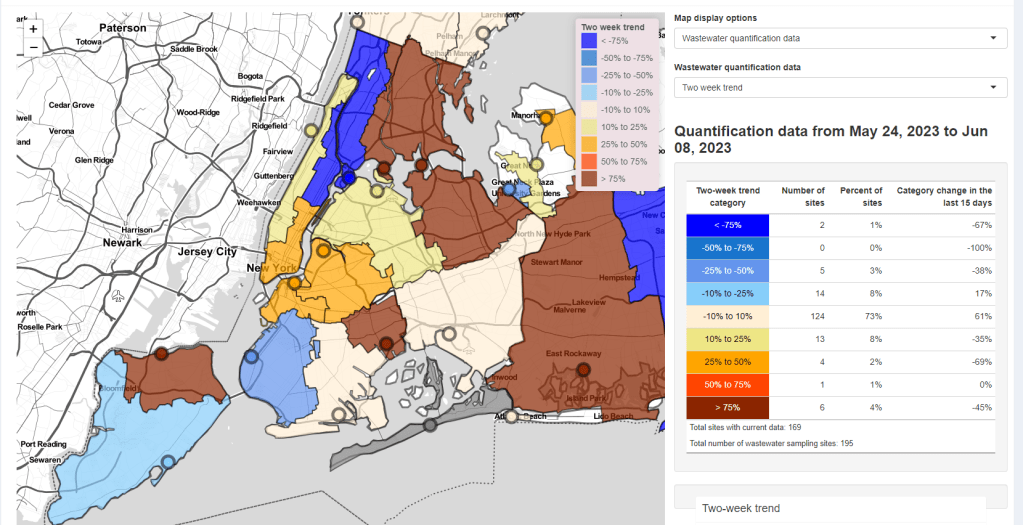

Some NYC sewershed have reported substantial increases in coronavirus levels in recent weeks. Screenshot from the New York State wastewater dashboard. In the past week (May 28 through June 3), the U.S. reported about 7,200 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 1,000 new admissions each day

- 2.2 total admissions for every 100,000 Americans

- 6% fewer new admissions than last week (May 21-27)

Additionally, the U.S. reported:

- 4.2% of tests in the CDC’s surveillance network came back positive (an 8% decrease from last week)

- 40% of new cases are caused by Omicron XBB.1.5; 26% by XBB.1.16; 21% by XBB.1.9 (as of June 10)

- (Biobot update delayed)

Nationally, the COVID-19 situation in the U.S. is similar to where we’ve been for the last few weeks. Major metrics (such as we have them) show an overall plateau in disease spread. Wastewater trends in a few places suggest a summer surge might be coming, but it’s hard to say for sure.

Hospital admissions and test positivity (from the specific network of labs reporting to the CDC) are trending slightly down at the national level. But there are still about 1,000 people being hospitalized with COVID-19 every day.

Biobot Analytics, my usual go-to source for wastewater surveillance data, did not update their dashboard this week due to a tech issue. The company’s most recent data, as of May 29, show plateaus in all four major regions.

The CDC’s National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS) shows a similar picture. Among about 1,100 sewage testing sites that recently reported to the CDC, 60% reported decreases in coronavirus levels in the last two weeks while 40% reported increases.

New York City is one of the places seeing wastewater increases, as I noted last week. Patterns differ somewhat across the city’s fourteen sewersheds, with some reporting more than 1000% increases in wastewater levels in recent weeks while others are still in plateaus.

Both the New York/New Jersey and New England regions are reporting slight upticks in their test positivity, according to the CDC’s surveillance network. This (along with the trends in NYC’s sewage) could be a precursor of more COVID-19 spread this summer, but it’s currently hard to say for sure.

The CDC updated its variant estimates (now reported every other week) this past Friday. XBB.1.5 is still the most common lineage, causing an estimated 40% of cases, the CDC reports. XBB.1.16 and XBB.1.9 continue to outcompete it, causing about 26% and 21% of cases respectively.

These newer lineages have yet to contribute to a significant shift in transmission, from what I can tell. We have yet to see if past immunity in the U.S. can hold off against the ever-evolving Omicron variants this summer.

-

Debt ceiling deal will mean even less COVID-19 funding

You’ve probably seen the news that last weekend, President Joe Biden and Congressional leaders reached a deal to raise the U.S. government’s debt ceiling. The deal passed both houses and Biden signed it yesterday.

In order to reach this bipartisan deal, Biden had to make a lot of compromises—including limiting funding for COVID-19 and other public health needs. The deal could make it harder for state and local governments to distribute COVID-19 vaccines, track disease through programs like wastewater surveillance, and prepare for future health threats.

The federal government is essentially taking back $27 billion of COVID-19 funds that it provided to various federal agencies, according to reporting by Ximena Bustillo and Tamara Keith at NPR. The move focuses on funds for programs that concluded or have “no immediate demands,” per a White House document shared by NPR.

But programs with “no immediate demands” could easily have demands in the coming months. One of NPR’s examples is funding for the federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to research and distribute vaccines, which can be distributed to other agencies (the CDC, NIH, FDA, state and local health departments, etc.). Vaccine distribution might not be a big need right now, but it likely will be in the fall, when new COVID-19 boosters become available.

Another potential need could be wastewater surveillance for COVID-19 and other health threats. The CDC’s National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS) was funded through 2025 by the American Rescue Plan, but it’s possible some of those funds could be in the HHS money pulled back by the debt ceiling deal. This would obviously be a huge loss for the U.S.’s ability to get early warning about future COVID-19 surges, as well as warnings about other pathogens. (Shout-out to Sean Kennedy for pointing this one out.)

In addition, the debt ceiling deal may lead to a smaller budget for the NIH, as Sarah Owermohle reports in STAT News. This could have implications for the agency’s ability to fund research into many pressing diseases, including Long COVID. The NIH has already wasted a lot of its Long COVID funding so far, according to my reporting, so it would be pretty bad news if more support for this research is not available.

The White House has claimed that Biden’s deal preserves funds for some key COVID-19 issues, according to NPR, including next-generation vaccines and Long COVID research. It’s hard to verify this, though, because of how convoluted federal COVID-19 funding has been. From a recent brief by the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials:

“Given the way Congress appropriated COVID-19 funding, and the way funding was later transferred between federal accounts and agencies, it is extremely difficult to discern which federal public health programs are affected by the rescissions.”

Public health funding often follows a cycle of “panic and neglect.” When a crisis occurs, governments panic and put tons of money into the immediate response. But after that crisis fades, it falls into neglect, with less money devoted to preparedness—even though preparedness efforts could help avert the next crisis. We’re clearly in that neglect part of the cycle for COVID-19 now; the debt ceiling deal is just the latest example.

More federal data

-

National numbers, June 4

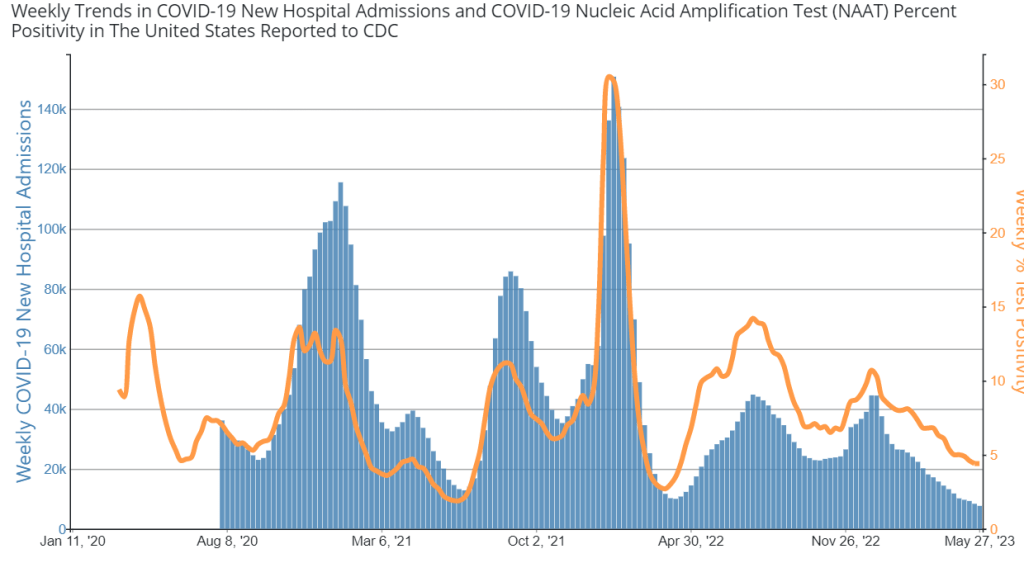

Both hospital admissions and test positivity for COVID-19 have ticked down in recent weeks. Chart via the CDC. In the past week (May 21 through 27), the U.S. reported about 7,600 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 1,100 new admissions each day

- 2.3 total admissions for every 100,000 Americans

- 8% fewer new admissions than last week (May 14-20)

Additionally, the U.S. reported:

- 4.4% of tests in the CDC’s surveillance network came back positive (a 0% change from last week)

- A 17% lower concentration of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater than last week (as of May 31, per Biobot’s dashboard)

- 54% of new cases are caused by Omicron XBB.1.5; 19% by XBB.1.16; 18% by XBB.1.9 (as of May 27)

The COVID-19 plateau of the last few weeks continues at the national level, though experts are concerned that a summer surge could occur in parts of the country. Wastewater surveillance and testing data are indicating potential increases in the New York City region.

Hospital admissions for COVID-19 remain at the levels we’ve seen throughout the spring, with about 1,100 people admitted nationwide each day last week. These numbers are similar to the hospitalizations reported at previous low points for COVID-19, in spring 2022 and 2021.

Testing data from the CDC’s National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System (NREVSS) also suggest a plateau: national test positivity didn’t change from last week to this week. While this CDC system includes a small fraction of the PCR labs that reported COVID-19 tests before the federal emergency ended, it’s still a helpful indicator for testing trends.

Wastewater surveillance data from Biobot shows a similar picture, with coronavirus levels in sewage remaining consistent at the national level for the last two months. All four major regions of the country are trending down, according to Biobot’s analysis.

But national data can hide more concerning trends at the local level. Wastewater data from New York City’s fourteen water treatment plants suggest potential increases in COVID-19 spread in the city and outlying suburbs over the last couple of weeks. The city’s wastewater data are reported with a delay (as of today, the most recent update was May 21), so I find it worrying that an increase may have predated the Memorial Day holiday. Test positivity data for the New York/New Jersey region suggest an uptick as well.

NYC has been a bellwether for the rest of the U.S. at many points during the pandemic, and it’s possible that the city could see a surge before other regions again this summer. Health experts are also closely watching the South, where people gather indoors more in the summer.

About 96% of Americans over age 16 have some COVID-19 protection from vaccination, past infections, or both, according to a recent CDC study. This protection will help many people avoid severe COVID-19 symptoms this summer even if they get infected. But Long COVID continues to be a risk—potentially even escalating with more infections.

-

Answering reader questions about wastewater data, rapid tests, Paxlovid

I wanted to highlight a couple of questions (and comments) that I’ve received recently from readers, hoping that they will be useful for others.

Interpreting wastewater surveillance data

One reader asked about how to interpret wastewater surveillance data, specifically looking at a California county on the WastewaterSCAN dashboard. She noticed that the dashboard includes both line charts (showing coronavirus trends over time) and heat maps (showing coronavirus levels), and asked: “I’m wondering what the difference is, and which is most relevant to following actual infection rates and trends?”

My response: Wastewater data can be messy because environmental factors can interfere with the results, and what may appear to be a trend may quickly change or reverse course (this FiveThirtyEight article I wrote last spring on the topic continues to be relevant). So a lot of dashboards use some kind of “risk level” metric in addition to showing linear trends in order to give users something a bit easier to interpret. See the “virus levels” categories on the CDC dashboard, for instance.

Personally, I like to look at trends over time to see if there might be an uptick in a particular location that I should worry about, but I find the risk level metrics to be more useful for actually following infection rates. Of course, every dashboard has its own process for calculating these levels—and we don’t yet have a good understanding of how wastewater data actually correlate to true community infections—so it’s helpful to also check out other metrics, like hospitalizations in your county.

Rapid test accuracy

Another reader asked: “Is there any data on the effectiveness of rapid tests for current variants like Arcturus? I’m hearing more and more that they are working less and less well as COVID evolves.”

My response: Unfortunately, I’m not aware of any specific data on rapid test effectiveness for recent variants. Early in the Omicron period, there were a few studies that showed the rapid tests still worked for that variant. The virus has obviously evolved a lot since then, but there is less interest in and fewer resources for evaluating these questions at this point in the pandemic, so it’s hard to say whether the continued mutations have had a significant impact on test effectiveness.

I think it’s important to flag, though, that rapid tests have never been highly accurate. People have tested negative on rapids—only to get a positive PCR the next day—since these tests were first introduced in spring 2021. The tests can be helpful for identifying if someone is contagious, with a high viral load, but are less accurate for people without symptoms. So, my recommendation with these tests is always to test multiple times, and to get a PCR if you have access to that. (Acknowledging there is less and less PCR access these days.) Also, if you were recently exposed to COVID-19, wait a few days to start rapid testing; see more details in this post from last year.

Double dose of Paxlovid

Another reader wrote in to share their experience with accessing Paxlovid during a recent COVID-19 case. The reader received a Paxlovid prescription, which led to a serious alleviation of symptoms. But when she experienced a rebound of symptoms after finishing the Paxlovid course, she had a hard time getting a second prescription.

“Fauci, Biden, head of Pfizer and CDC director got a second course of Paxlovid prescribed to them,” the reader wrote. “When I attempted to get this, my doctors pretended I was crazy and said this was never done.” She added that she’d like to publicize the two-course Paxlovid option.

My response: I appreciate this reader sharing her experience, and I hope others can consider getting multiple Paxlovid prescriptions for a COVID-19 case. The FDA just provided full approval to Pfizer for the drug, which should alleviate some bureaucratic hurdles to access. I also know that current clinical trials testing Paxlovid as a potential Long COVID treatment are using a longer course; 15 days rather than five days. The results of those trials may provide some evidence to support a longer course overall.

If you have a COVID-19 question, please send me an email and I’ll respond in a future issue!

-

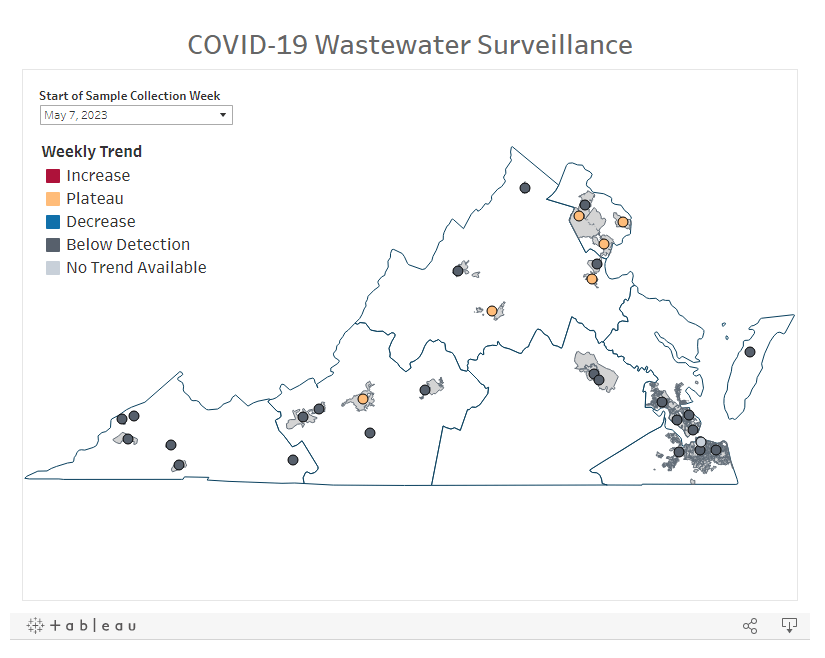

COVID source shout-out: Virginia’s new wastewater dashboard

One of the visuals available on Virginia’s new wastewater dashboard. With the public health emergency ending, a lot of state and local health departments are sunsetting or paring down their COVID-19 dashboards. Wastewater surveillance data are an exception, though, with agencies continuing to test sewage (and share the results) as other forms of COVID-19 testing become less available.

Virginia’s Department of Health is one notable example: this past week, the agency added a new wastewater surveillance section to its COVID-19 dashboard. The new section includes a map of testing sites, coronavirus trends by site, viral loads over time, and plenty of text explaining how to interpret the data.

This dashboard will be a great resource for Virginia residents aiming to continue following COVID-19 spread in their communities. It’ll be updated weekly on Tuesdays, according to the department.

-

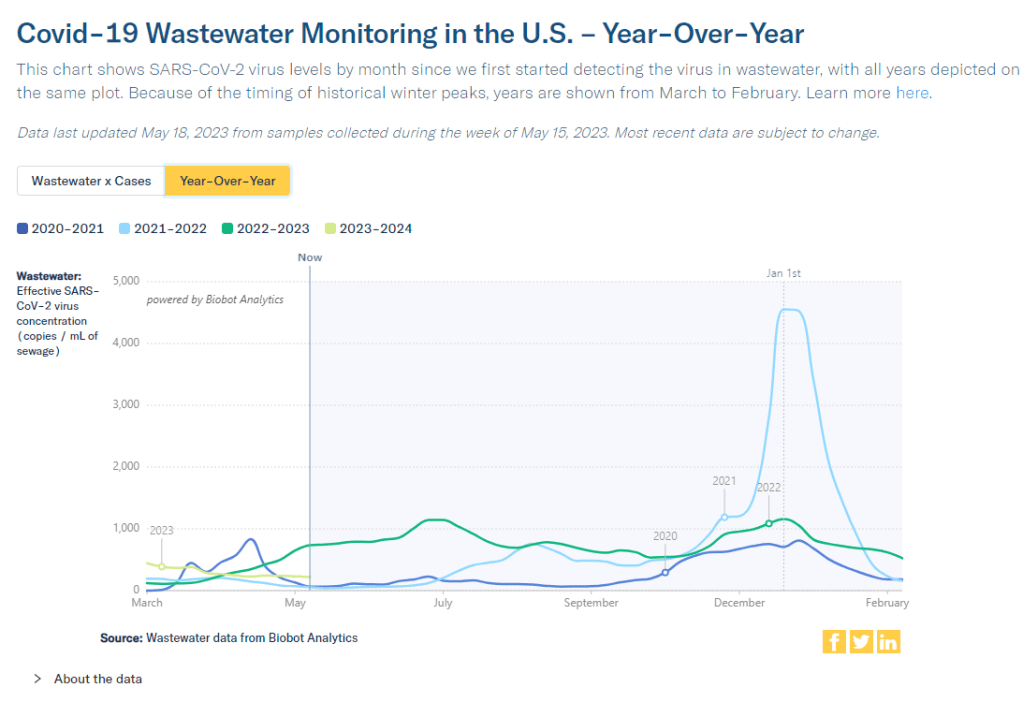

National numbers, May 21

According to wastewater data from Biobot, COVID-19 spread right now is lower than at this time last year, but higher than the prior two years. In the past week (May 7 through 13), the U.S. reported about 9,200 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 1,300 new admissions each day

- 2.8 total admissions for every 100,000 Americans

- 5% fewer new admissions than last week (April 30-May 6)

Additionally, the U.S. reported:

- A 4% lower concentration of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater than last week (as of May 17, per Biobot’s dashboard)

- 64% of new cases are caused by Omicron XBB.1.5; 13% by XBB.1.9; 14% by XBB.1.16 (as of May 13)

- An average of 75,000 vaccinations per day

Nationwide, COVID-19 spread in the U.S. continues to be in a somewhat-middling plateau: lower than the massive amount of Omicron transmission we all got used to throughout late 2022, but still higher than the lulls between outbreaks we saw in prior years.

Biobot’s national wastewater surveillance offers a helpful visual for this comparison. As of May 20, the company calculates a national average of 221 viral copies per milliliter of sewage (a common unit for quantifying SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater), based on hundreds of sewage testing sites in its network.

In late May of last year, when early Omicron offshoots were spreading widely, this value was several times higher: 736 viral copies per milliliter. But around the same time in 2021 (when millions of Americans were getting their first vaccine shots) or 2020 (when the very first big surge had ended), wastewater concentrations were under 100 viral copies per milliliter.

It’s also important to note that wastewater concentrations have been fairly level for a couple of months now, both nationally and for all four major regions. High immunity across the population and a lack of divergent new variants have kept us from seeing a new surge since the 2022 winter holidays; but without widespread safety measures, I suspect we’re unlikely to see a drop in transmission below the current baseline.

Hospital admissions, now the CDC’s primary metric for tracking this disease, show a similar picture to the wastewater data. Numbers are low and ticking ever-so-slightly downward, but they’re not zero: about 1,300 people were admitted to hospitals with COVID-19 each day in the week ending May 13.

Deaths with COVID-19 also remain at low yet significant numbers. While the CDC reports only 281 deaths in the last week, this information is now presented with a greater delay than during the federal public health emergency, as the agency had to switch from death reports received directly from states to death certificate data. For the week ending May 6, the CDC revised its number up from about 300 to 622 COVID-19 deaths.

There are no changes to variant estimates this week, as the CDC is now updating that data every other week rather than weekly. XBB.1.5 remains the dominant variant, with XBB.1.16 and XBB.1.19 slowly gaining ground.

Overall, it’s getting harder to identify detailed COVID-19 trends, but a lot of data still do remain available. I’ll keep providing updates as best I can.

-

COVID source shout-out: Wastewater testing at the San Francisco airport

A few months ago, I wrote about how testing sewage from airplanes could be a valuable way to keep tabs on the coronavirus variants circulating around the world. International travel is the main way that new variants get from one country to another, so monitoring those travelers’ waste could help health officials quickly spot—and respond to—the virus’ continued mutations.

This spring, San Francisco International Airport became the first in the U.S. to actually start doing this tracking; I covered their new initiative for Science News. The airport is working with the CDC and Concentric, a biosecurity and public health team at the biotech company Ginkgo Bioworks, which already collaborates with the agency on monitoring travelers through PCR tests.

The San Francisco airport started collecting samples on April 20, and scientists at Concentric told me that they’re happy with how it’s going so far. Airport staff are collecting one sample each day, with each one representing a composite of many international flights. Parsing out the resulting data won’t be easy, but the scientists hope to learn lessons from this program that they can take to other surveillance projects.

Both scientists at Concentric and outside experts are also excited about the potential to monitor other novel pathogens through airplane waste (though the San Francisco project is focused on coronavirus variants right now). Read my Science News story for more details!

-

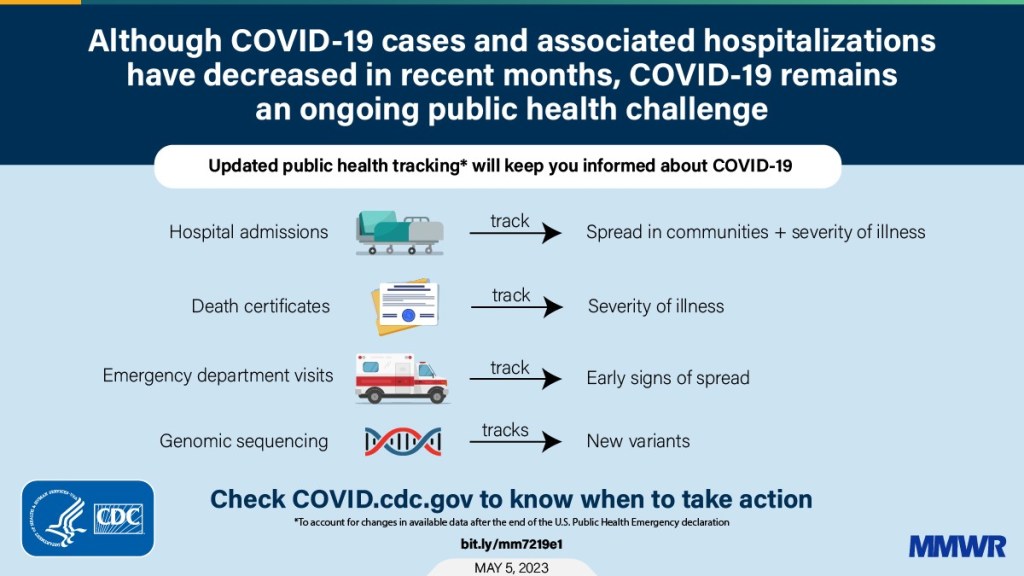

The federal public health emergency ends next week: What you should know

A chart from the CDC’s recent report on surveillance changes tied to the end of the federal public health emergency. We’re now less than one week out from May 11, when the federal public health emergency (or PHE) for COVID-19 will end. While this change doesn’t actually signify that COVID-19 is no longer worth worrying about, it marks a major shift in how U.S. governments will respond to the ongoing pandemic, including how the disease is tracked and what public services are available.

I’ve been writing about this a lot in the last couple of months, cataloging different aspects of the federal emergency’s end. But I thought it might be helpful for readers if I compiled all the key information in one place. This post also includes a few new insights about how COVID-19 surveillance will change after May 11, citing the latest CDC reports.

What will change overall when the PHE ends?

The ending of the PHE will lead to COVID-19 tests, treatments, vaccines, and data becoming less widely available across the U.S. It may also have broader implications for healthcare, with telehealth policies shifting, people getting kicked off of Medicaid, and other changes.

Last week, I attended a webinar about these changes hosted by the New York City Pandemic Response Institute. The webinar’s moderator, City University of New York professor Bruce Y. Lee, kicked it off with a succinct list of direct and indirect impacts of the PHE’s end. These were his main points:

- Free COVID-19 vaccines, tests, and treatments will run out after the federal government’s supplies are exhausted. (Health experts project that this will likely happen sometime in fall 2023.) At that point, these services will get more expensive and harder to access as they transition to private healthcare markets.

- We will have fewer COVID-19 metrics (and less complete data) to rely on as the CDC and other public health agencies change their surveillance practices. More on this below.

- Many vaccination requirements are being lifted. This applies to federal government mandates as well as many from state/local governments and individual businesses.

- The FDA will phase out its Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs) for COVID-19 products, encouraging manufacturers to apply for full approval. (This doesn’t mean we’ll suddenly stop being able to buy at-home tests—there’s going to be a long transition process.)

- Healthcare worker shortages may get worse. During the pandemic emergency, some shifts to work requirements allowed facilities to hire more people, more easily; as these policies are phased out, some places may lose those workers.

- Millions of people will lose access to Medicaid. A federal rule tied to the PHE forbade states from kicking people off this public insurance program during the pandemic, leading to record coverage. Now, states are reevaluating who is eligible. (This process actually started in April, before the official PHE end.)

- Telehealth options may become less available. As with healthcare hiring, policies during the PHE made it easier for doctors to provide virtual care options, like video-call appointments and remote prescriptions. Some of these COVID-era rules will be rolled back, while others may become permanent.

- People with Long COVID will be further left behind, as the PHE’s end leads many people to distance themselves even more from the pandemic—even though long-haulers desperately need support. This will also affect people who are at high risk for COVID-19 and continue to take safety precautions.

- Pandemic research and response efforts may be neglected. Lee referenced the “panic and neglect” cycle for public health funding: a pattern in which governments provide resources when a crisis happens, but then fail to follow through during less dire periods. The PHE’s end will likely lead us (further) into the “neglect” part of this cycle.

How will COVID-19 data reporting change?

The CDC published two reports this week that summarize how national COVID-19 data reporting will change after May 11. One goes over the surveillance systems that the CDC will use after the PHE ends, while the other discusses how different COVID-19 metrics correlate with each other.

A lot of the information isn’t new, such as the phasing out of Community Level metrics for counties (which I covered last week). But it’s helpful to have all the details in one place. Here are a few things that stuck out to me:

- Hospital admissions will be the CDC’s primary metric for tracking trends in COVID-19 spread rather than cases. While more reliable than case counts, hospitalizations are a lagging metric—it takes typically days (or weeks) after infections go up for the increase to show up at hospitals, since people don’t seek medical care immediately. The CDC will recieve reports from hospitals at a weekly cadence, rather than daily, after May 11, likely increasing this lag and making it harder for health officials to spot new surges.

- National case counts will no longer be available as PCR labs will no longer be required to report their data to the CDC. PCR test totals and test positivity rates will also disappear for the same reason, as will the Community Levels that were determined partially by cases. The CDC will also stop reporting real(ish)-time counts of COVID-associated deaths, relying instead on death certificates.

- Deaths will be the primary metric for tracking how hard COVID-19 is hitting the U.S. The CDC will get this information from death certificates via the National Vital Statistics System. While deaths are reported with a significant lag (at least two weeks), the agency has made a lot of progress on modernizing this reporting system during the pandemic. (See this December 2021 post for more details.)

- The CDC will utilize sentinel networks and electronic health records to gain more information about COVID-19 spread. This includes the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System, a network of about 450 laboratories that submit testing data to the CDC (previously established for other endemic diseases like RSV and norovirus). It also includes the National Syndromic Surveillance Program, a network of 6,300 hospitals that submit patient data to the agency.

- Variant surveillance will continue, using a combination of PCR samples and wastewater data. The CDC’s access to PCR swab samples will be seriously diminished after May 11, so it will have to work with public health labs to develop national estimates from the available samples. Wastewater will help fill in these gaps; a few wastewater testing sites already send the CDC variant data. And the CDC will continue offering tests to international travelers entering the country, for a window into global variant patterns.

- The CDC will continue tracking vaccinations, vaccine effectiveness, and vaccine safety. Vaccinations are generally tracked at the state level (every state health agency, and several large cities, have their own immunization data systems), but state agencies have established data sharing agreements with the CDC that are set to continue past May 11. The CDC will keep using its established systems for evaluating how well the vaccines work and tracking potential safety issues as well.

- Long COVID notably is not mentioned in the CDC’s reports. The agency hasn’t put much focus on tracking long-term symptoms during the first three years of the pandemic, and it appears this will continue—even though Long COVID is a severe outcome of COVID-19, just like hospitalization or death. A lack of focus on tracking Long COVID will make it easier for the CDC and other institutions to keep minimizing this condition.

On May 11, the CDC plans to relaunch its COVID-19 tracker to incorporate all of these changes. The MMWR on surveillance changes includes a list of major pages that will shift or be discontinued at this time.

Overall, the CDC will start tracking COVID-19 similar to the way it tracks other endemic diseases. Rather than attempting to count every case, it will focus on certain severe outcomes (i.e., hospitalizations and deaths) and extrapolate national patterns from a subset of healthcare facilities with easier-to-manage data practices. The main exception, I think, will be a focus on tracking potential new variants, since the coronavirus is mutating faster and more aggressively than other viruses like the flu.

What should I do to prepare for May 11?

If you’ve read this far, you’re probably concerned about how all these shifts will impact your ability to stay safe from COVID-19. Unfortunately, the CDC, like many other public agencies, is basically leaving Americans to fend for themselves with relatively little information or guidance.

But a lot of information sources (like this publication) are going to continue. Here are a few things I recommend doing this week as the PHE ends:

- Look at your state and local public health agencies to see how they’re responding to the federal shift. Some COVID-19 dashboards are getting discontinued, but many are sticking around; your local agency will likely have information that’s more tailored to you than what the CDC can offer.

- Find your nearest wastewater data source. With case counts basically going away, wastewater surveillance will be our best source for early warnings about surges. You can check the COVID-19 Data Dispatch list of wastewater dashboards and/or the COVIDPoops dashboard for sources near you.

- Stock up on at-home tests and masks. This is your last week to order free at-home/rapid tests from your insurance company if you have private insurance. It’s also a good time to buy tests and masks; many distributors are having sales right now.

- Figure out where you might get a PCR test and/or Paxlovid if needed. These services will be harder to access after May 11; if you do some logistical legwork now, you may be more prepared for when you or someone close to you gets sick. The People’s CDC has some information and links about this.

- Contact your insurance company to find out how their COVID-19 coverage policies are changing, if you have private insurance. Folks on Medicare and Medicaid: this Kaiser Family Foundation article has more details about changes for you.

- Ask people in your community how you can help. This is a confusing and isolating time for many Americans, especially people at higher risk for COVID-19. Reaching out to others and offering some info or resources (maybe even sharing this post!) could potentially go a long way.

That was a lot of information packed into one post. If you have questions about the ending PHE (or if I missed any important details), please email me or leave a comment below—and I’ll try to answer in next week’s issue.

More about federal data