We’re now less than one week out from May 11, when the federal public health emergency (or PHE) for COVID-19 will end. While this change doesn’t actually signify that COVID-19 is no longer worth worrying about, it marks a major shift in how U.S. governments will respond to the ongoing pandemic, including how the disease is tracked and what public services are available.

I’ve been writing about this a lot in the last couple of months, cataloging different aspects of the federal emergency’s end. But I thought it might be helpful for readers if I compiled all the key information in one place. This post also includes a few new insights about how COVID-19 surveillance will change after May 11, citing the latest CDC reports.

What will change overall when the PHE ends?

The ending of the PHE will lead to COVID-19 tests, treatments, vaccines, and data becoming less widely available across the U.S. It may also have broader implications for healthcare, with telehealth policies shifting, people getting kicked off of Medicaid, and other changes.

Last week, I attended a webinar about these changes hosted by the New York City Pandemic Response Institute. The webinar’s moderator, City University of New York professor Bruce Y. Lee, kicked it off with a succinct list of direct and indirect impacts of the PHE’s end. These were his main points:

- Free COVID-19 vaccines, tests, and treatments will run out after the federal government’s supplies are exhausted. (Health experts project that this will likely happen sometime in fall 2023.) At that point, these services will get more expensive and harder to access as they transition to private healthcare markets.

- We will have fewer COVID-19 metrics (and less complete data) to rely on as the CDC and other public health agencies change their surveillance practices. More on this below.

- Many vaccination requirements are being lifted. This applies to federal government mandates as well as many from state/local governments and individual businesses.

- The FDA will phase out its Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs) for COVID-19 products, encouraging manufacturers to apply for full approval. (This doesn’t mean we’ll suddenly stop being able to buy at-home tests—there’s going to be a long transition process.)

- Healthcare worker shortages may get worse. During the pandemic emergency, some shifts to work requirements allowed facilities to hire more people, more easily; as these policies are phased out, some places may lose those workers.

- Millions of people will lose access to Medicaid. A federal rule tied to the PHE forbade states from kicking people off this public insurance program during the pandemic, leading to record coverage. Now, states are reevaluating who is eligible. (This process actually started in April, before the official PHE end.)

- Telehealth options may become less available. As with healthcare hiring, policies during the PHE made it easier for doctors to provide virtual care options, like video-call appointments and remote prescriptions. Some of these COVID-era rules will be rolled back, while others may become permanent.

- People with Long COVID will be further left behind, as the PHE’s end leads many people to distance themselves even more from the pandemic—even though long-haulers desperately need support. This will also affect people who are at high risk for COVID-19 and continue to take safety precautions.

- Pandemic research and response efforts may be neglected. Lee referenced the “panic and neglect” cycle for public health funding: a pattern in which governments provide resources when a crisis happens, but then fail to follow through during less dire periods. The PHE’s end will likely lead us (further) into the “neglect” part of this cycle.

How will COVID-19 data reporting change?

The CDC published two reports this week that summarize how national COVID-19 data reporting will change after May 11. One goes over the surveillance systems that the CDC will use after the PHE ends, while the other discusses how different COVID-19 metrics correlate with each other.

A lot of the information isn’t new, such as the phasing out of Community Level metrics for counties (which I covered last week). But it’s helpful to have all the details in one place. Here are a few things that stuck out to me:

- Hospital admissions will be the CDC’s primary metric for tracking trends in COVID-19 spread rather than cases. While more reliable than case counts, hospitalizations are a lagging metric—it takes typically days (or weeks) after infections go up for the increase to show up at hospitals, since people don’t seek medical care immediately. The CDC will recieve reports from hospitals at a weekly cadence, rather than daily, after May 11, likely increasing this lag and making it harder for health officials to spot new surges.

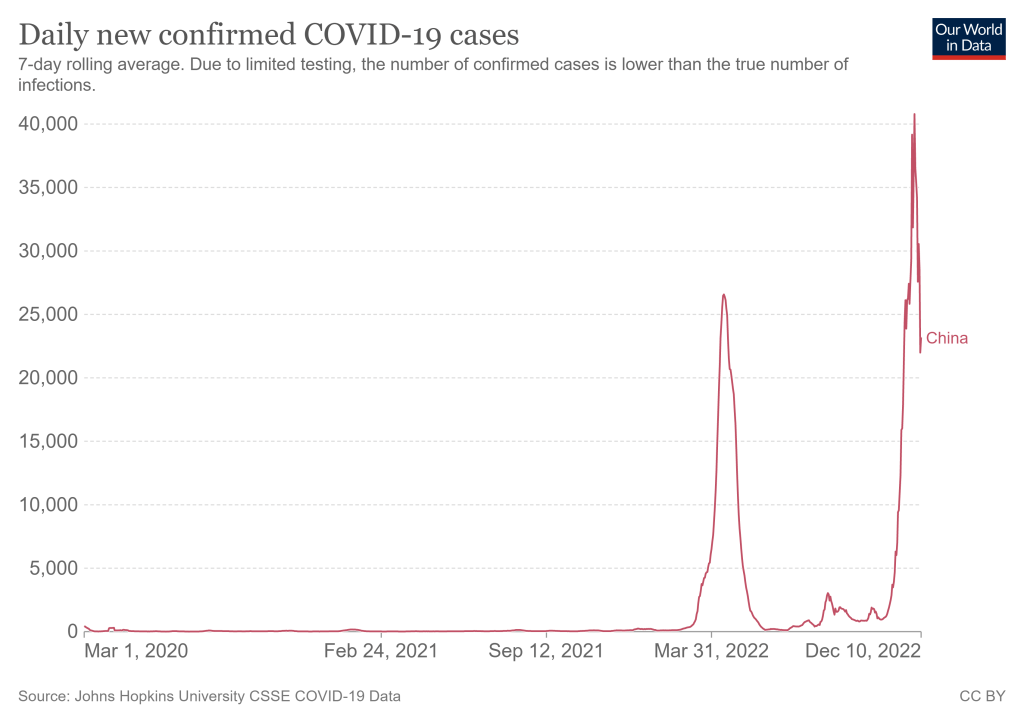

- National case counts will no longer be available as PCR labs will no longer be required to report their data to the CDC. PCR test totals and test positivity rates will also disappear for the same reason, as will the Community Levels that were determined partially by cases. The CDC will also stop reporting real(ish)-time counts of COVID-associated deaths, relying instead on death certificates.

- Deaths will be the primary metric for tracking how hard COVID-19 is hitting the U.S. The CDC will get this information from death certificates via the National Vital Statistics System. While deaths are reported with a significant lag (at least two weeks), the agency has made a lot of progress on modernizing this reporting system during the pandemic. (See this December 2021 post for more details.)

- The CDC will utilize sentinel networks and electronic health records to gain more information about COVID-19 spread. This includes the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System, a network of about 450 laboratories that submit testing data to the CDC (previously established for other endemic diseases like RSV and norovirus). It also includes the National Syndromic Surveillance Program, a network of 6,300 hospitals that submit patient data to the agency.

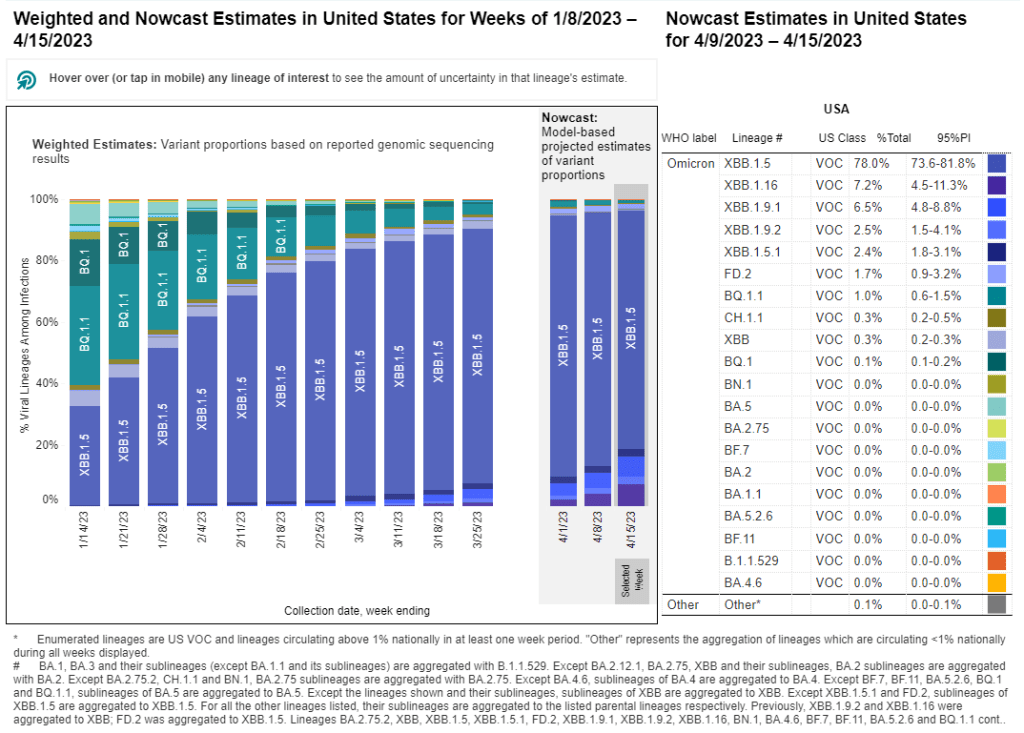

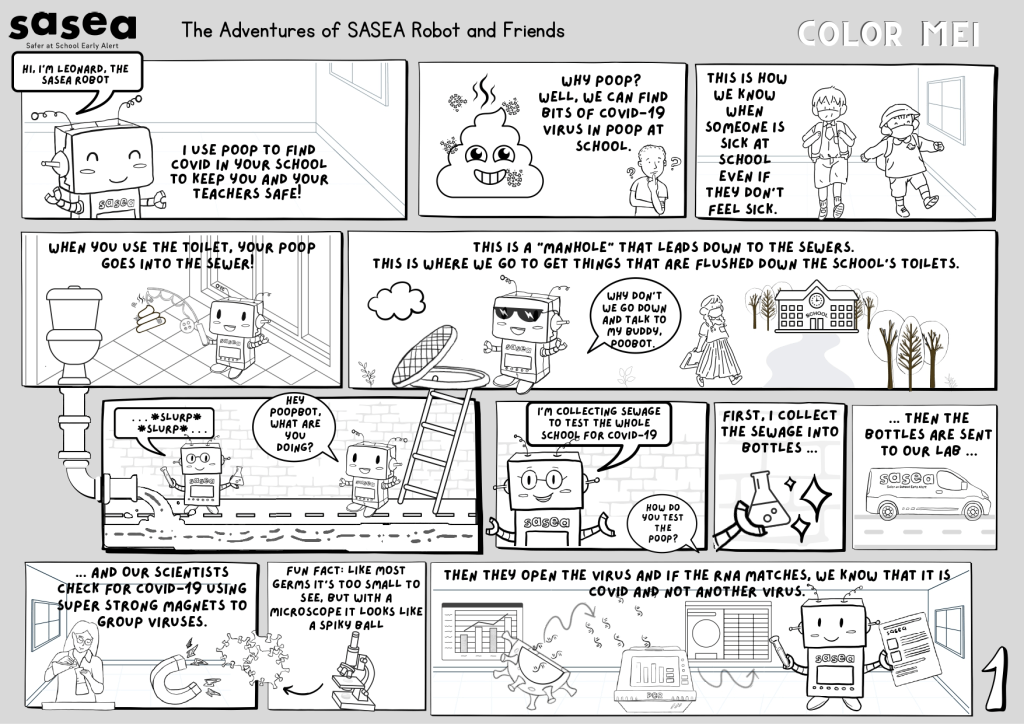

- Variant surveillance will continue, using a combination of PCR samples and wastewater data. The CDC’s access to PCR swab samples will be seriously diminished after May 11, so it will have to work with public health labs to develop national estimates from the available samples. Wastewater will help fill in these gaps; a few wastewater testing sites already send the CDC variant data. And the CDC will continue offering tests to international travelers entering the country, for a window into global variant patterns.

- The CDC will continue tracking vaccinations, vaccine effectiveness, and vaccine safety. Vaccinations are generally tracked at the state level (every state health agency, and several large cities, have their own immunization data systems), but state agencies have established data sharing agreements with the CDC that are set to continue past May 11. The CDC will keep using its established systems for evaluating how well the vaccines work and tracking potential safety issues as well.

- Long COVID notably is not mentioned in the CDC’s reports. The agency hasn’t put much focus on tracking long-term symptoms during the first three years of the pandemic, and it appears this will continue—even though Long COVID is a severe outcome of COVID-19, just like hospitalization or death. A lack of focus on tracking Long COVID will make it easier for the CDC and other institutions to keep minimizing this condition.

On May 11, the CDC plans to relaunch its COVID-19 tracker to incorporate all of these changes. The MMWR on surveillance changes includes a list of major pages that will shift or be discontinued at this time.

Overall, the CDC will start tracking COVID-19 similar to the way it tracks other endemic diseases. Rather than attempting to count every case, it will focus on certain severe outcomes (i.e., hospitalizations and deaths) and extrapolate national patterns from a subset of healthcare facilities with easier-to-manage data practices. The main exception, I think, will be a focus on tracking potential new variants, since the coronavirus is mutating faster and more aggressively than other viruses like the flu.

What should I do to prepare for May 11?

If you’ve read this far, you’re probably concerned about how all these shifts will impact your ability to stay safe from COVID-19. Unfortunately, the CDC, like many other public agencies, is basically leaving Americans to fend for themselves with relatively little information or guidance.

But a lot of information sources (like this publication) are going to continue. Here are a few things I recommend doing this week as the PHE ends:

- Look at your state and local public health agencies to see how they’re responding to the federal shift. Some COVID-19 dashboards are getting discontinued, but many are sticking around; your local agency will likely have information that’s more tailored to you than what the CDC can offer.

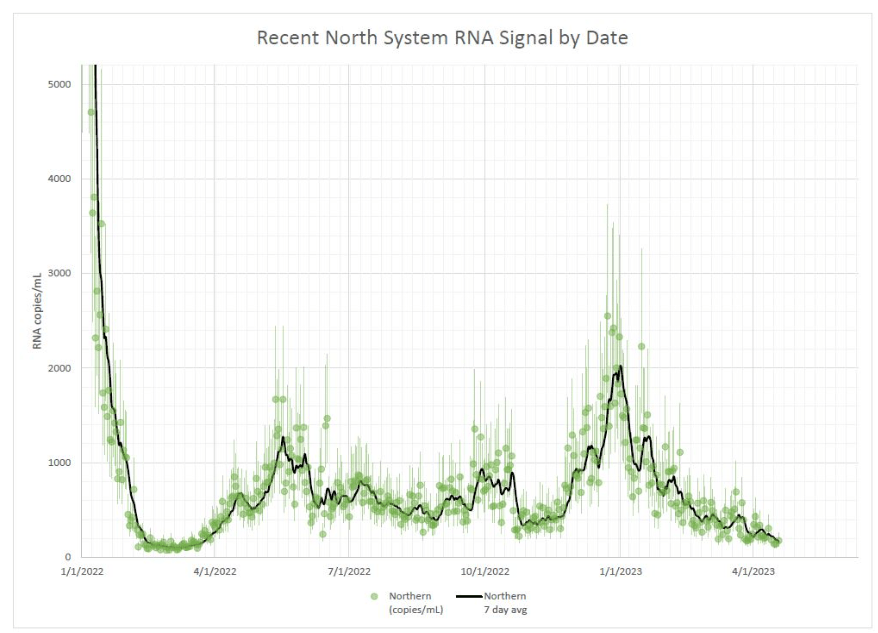

- Find your nearest wastewater data source. With case counts basically going away, wastewater surveillance will be our best source for early warnings about surges. You can check the COVID-19 Data Dispatch list of wastewater dashboards and/or the COVIDPoops dashboard for sources near you.

- Stock up on at-home tests and masks. This is your last week to order free at-home/rapid tests from your insurance company if you have private insurance. It’s also a good time to buy tests and masks; many distributors are having sales right now.

- Figure out where you might get a PCR test and/or Paxlovid if needed. These services will be harder to access after May 11; if you do some logistical legwork now, you may be more prepared for when you or someone close to you gets sick. The People’s CDC has some information and links about this.

- Contact your insurance company to find out how their COVID-19 coverage policies are changing, if you have private insurance. Folks on Medicare and Medicaid: this Kaiser Family Foundation article has more details about changes for you.

- Ask people in your community how you can help. This is a confusing and isolating time for many Americans, especially people at higher risk for COVID-19. Reaching out to others and offering some info or resources (maybe even sharing this post!) could potentially go a long way.

That was a lot of information packed into one post. If you have questions about the ending PHE (or if I missed any important details), please email me or leave a comment below—and I’ll try to answer in next week’s issue.