- CDC investigating deaths from Long COVID: Researchers at the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics are currently working to investigate potential deaths from Long COVID, according to a report from POLITICO. The researchers are reviewing death certificates from 2020 and 2021, looking for causes of death that may indicate a patient died from Long COVID symptoms rather than during the acute stage of the disease. There’s currently no death code associated with Long COVID and diagnoses can be highly variable, so the work is preliminary, but I’m really looking forward to seeing their results.

- CDC reports on ventilation improvements in schools: And one notable CDC study that was published this week: researchers at the agency from COVID-19, occupational health, and other teams analyzed what K-12 public schools are doing to improve their ventilation. The report is based on a survey of 420 public schools in all 50 states and D.C., with results weighted to best represent all schools across the country. While a majority of schools have taken some measures to inspect their HVAC systems or increase ventilation by opening windows, holding activities outside, etc., only 39% of schools surveyed had actually replaced or upgraded their HVAC systems. A lot more work is needed in this area.

- Results from the COVID-19 U.S. State Policy database: The Boston University team behind the COVID-19 U.S. State Policy database has published a paper in BMC Public Health sharing major findings from their work. The database (which I’ve shared in the CDD before) documents what states have done to curb COVID-19 spread and address economic hardship during the pandemic, as well as how states report COVID-19 data. In their new paper, the BU team explains how this database may be used to analyze the impacts of these policy measures on public health.

- Promising news about Moderna’s bivalent vaccine: Moderna, like other vaccine companies, has been working on versions of its COVID-19 vaccine that can protect better against new variants like Omicron. This week, the company announced results (in a press release, as usual) from a trial of a bivalent vaccine, which includes both genetic elements of the original SARS-CoV-2 virus and of Omicron. The bivalent vaccine works much better than Moderna’s original vaccine at protecting against Omicron infection, Moderna said; still, scientists are skeptical about how the vaccine may fare against newer subvariants (BA.2.12.1, BA.4, BA.5).

- Call center and survey from FYLPRO: A reader who works at the Filipino Young Leaders Program (FYLPRO) requested that I share two resources from their organization. First, the program has set up a call center aimed at helping vulnerable community members with their COVID-19 questions. The call center is available on weekdays from 9 A.M. to 5 P.M. Pacific time in both English and Tagalog; while it’s geared towards the Filipino community, anyone can call in. And second, FYLPRO has launched a nationwide survey to study vaccine attitudes among Filipinos; learn more about it here.

Tag: vaccine results

-

Sources and updates, June 12

-

Sources and updates, May 15

- COVID-19 deaths that could’ve been prevented with vaccines: A new analysis from the Brown University School of Public Health suggests that almost 319,000 U.S. COVID-19 deaths could have been avoided if all adults had gotten vaccinated against the disease. This number differs significantly by state; there were 29,000 preventable COVID-19 deaths in Florida, compared to under 300 in Vermont. For more context on the analysis, see this article in NPR.

- CDC dashboard in Spanish: The CDC has translated its COVID-19 Data Tracker into Español. At a glance, the Spanish version appears to include all the major aspects of the tracker: cases, deaths, vaccinations, community transmission, variant prevalence, wastewater, etc. Of course, it would have been great if the agency could’ve devoted resources to this translation effort well below spring 2022, when the number of people looking to the agency for COVID-19 guidance is pretty low.

- CDC may lose access to COVID-19 data: According to reporting from POLITICO, the CDC and other national health agencies may no longer have the authority to require COVID-19 data reporting from states and individual health institutions if the Biden administration allows the country’s federal pandemic health emergency to end this summer. Such a change in authority could lead to the CDC (and numerous other researchers across the country) losing standardized datasets for COVID-19 hospitalizations, transmission in nursing homes, PCR testing, and other key metrics. Considering that hospitalizations are considered the most reliable metric right now, this could be a major blow.

- COVID-19 testing declines globally: Speaking of losing reliable data: this report from the Associated Press caught my eye. The story, by Laura Ungar, explains that the U.S. is not the only country to see a major decrease in reported COVID-19 tests (a.k.a. Lab-based PCR, not at-home rapid tests) in recent months. “Experts say testing has dropped by 70 to 90% worldwide from the first to the second quarter of this year,” Ungar writes, “the opposite of what they say should be happening with new omicron variants on the rise in places such as the United States and South Africa.”

- More promising data on Moderna kids’ vaccine: While Pfizer’s vaccine for children under five remains in development, Moderna continues to release data suggesting that this company is further ahead in providing protection for the youngest age group. This week, Moderna announced a half-dose of its vaccine provides a “strong immune response” in children ages six to 11; the announcement was backed up by a scientific study published in the New England Journal of Medicine (so, more rigorous than your typical press release). The FDA is currently evaluating a version of Moderna’s vaccine for children between ages six months and six years.

-

The US still doesn’t have the data we need to make informed decisions on booster shots

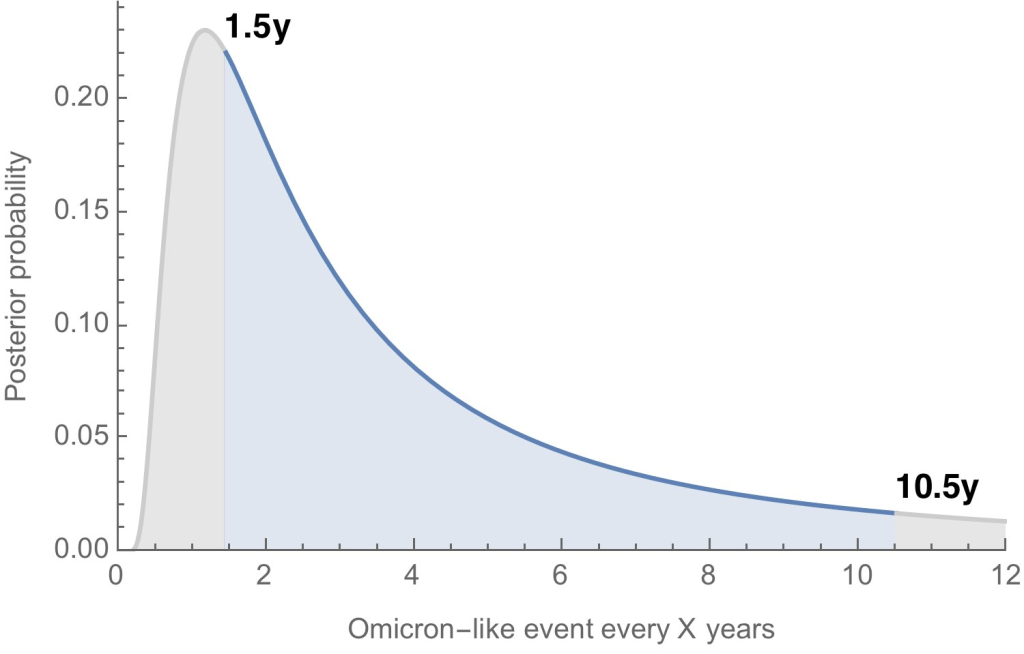

How often will we see new variants like Omicron, that are incredibly different from other lineages that came before them? According to Trevor Bedford, it could be between 1.5 and 10.5 years. Last fall, I wrote—both in the COVID-19 Data Dispatch and for FiveThirtyEight—that the U.S. did not have the data we needed to make informed decisions about booster shots. Several months later, we still don’t have the data we need, as questions about a potential BA.2 wave and other future variants abound. Discussions at a recent FDA advisory committee meeting made these data gaps clear.

Our country has a fractured public health system: every state health department has its own data systems for COVID-19 cases, vaccinations, and other metrics, and these data systems are often very difficult to link up with each other. This can make it difficult to answer questions about vaccine effectiveness, especially when you want to get specific about different age groups, preexisting conditions, or variants.

To quote from my November FiveThirtyEight story:

In the U.S., vaccine research is far more complicated. Rather than one singular, standardized system housing health care data, 50 different states have their own systems, along with hundreds of local health departments and thousands of hospitals. “In the U.S., everything is incredibly fragmented,” said Zoë McLaren, a health economist at the University of Maryland Baltimore County. “And so you get a very fragmented view of what’s going on in the country.”

For example, a database on who’s tested positive in a particular city might not be connected to a database that would reveal which of those patients was vaccinated. And that database, in turn, is probably not connected to health records showing which patients have a history of diabetes, heart disease or other conditions that make people more vulnerable to COVID-19.

Each database has its own data fields and definitions, making it difficult for researchers to integrate records from different sources. Even basic demographics such as age, sex, race and ethnicity may be logged differently from one database to the next, or they may simply be missing. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for instance, is missing race and ethnicity information for 35 percent of COVID-19 cases as of Nov. 7.*

*As of April 9, the CDC is still missing race and ethnicity information for 35% of COVID-19 cases.

This past Wednesday, the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) met to discuss the future of COVID-19 booster shots. Notably, this committee didn’t actually need to vote on anything, since the FDA and CDC had already authorized a second round of boosters for Americans over age 50 and immunocompromised people the week before.

When asked why the FDA hadn’t waited to hear from its advisory committee before making this authorization decision, vaccine regulator Peter Marks said that the agency had relied on data from the U.K. and Israel to demonstrate the need for more boosters—combined with concerns about a potential BA.2 wave. The FDA relied on data from the U.K. and Israel when making its booster decision in the fall, too; these countries, with centralized health systems and better-organized data, are much more equipped to track vaccine effectiveness than we are.

With that authorization of second boosters for certain groups already a done deal, the VRBPAC meeting this past Wednesday focused more on the information we need to make future booster decisions. Should we expect annual COVID-19 shots, like we do for the flu? What about shots that are designed to combat specific variants? A lot of this is up in the air right now, the meeting discussion indicated.

Also up in the air: will the FDA ever host a virtual VRBPAC meeting without intensive technical difficulties? The meeting had to pause for more than half an hour to sort out a livestream issue.

Here are some vaccine data questions that came up on Wednesday, drawing from my own notes on the meeting and the STAT News liveblog:

- How much does protection from a booster shot wane over time? We know that booster shots increase an individual’s protection from a coronavirus infection, symptoms, hospitalization, and other severe outcomes; CDC data presented during the VRBPAC meeting showed that, during the Omicron surge, Americans who were boosted were much more protected than those with fewer doses. But we don’t have a great sense of how long these different types of protection last.

- How much does booster shot protection wane for different age groups? Waning immunity has been a bigger problem among seniors and immunocompromised people, leading to the FDA’s decision on fourth doses for these groups. But what about other age groups? What about people with other conditions that make them vulnerable to COVID-19, like diabetes or kidney disease? This is less clear.

- To what degree is waning immunity caused by new variants as opposed to fewer antibodies over time? This has been a big question during the Delta and Omicron surges, and it can be hard to answer because of all the confounding variables involved. In the U.S., it’s difficult to link up vaccine data and case data; tacking on metrics like which variant someone was infected with or how long ago they were vaccinated often isn’t possible—or if it is possible, it’s very complicated. (The U.K. does a better job of this.)

- Where will the next variant of concern come from, and how much will it differ from past variants? Computational biologist Trevor Bedford gave a presentation to VRBPAC that attempted to answer this question. The short answer is, it’s hard to predict how often we’ll see new events like Omicron’s emergence, in which a new variant comes in that is extremely different from the variants that preceded it. Bedford’s analysis suggests that we could see “Omicron-like” events anywhere from every 1.5 years to every 10.5 years, and we should be prepared for anything on that spectrum. The coronavirus has evolved quite quickly in the last two years, Bedford said, and will likely continue to do so; though he expects some version of Omicron will be the main variant we’re dealing with for a while.

- What will the seasonality of COVID-19 be? The global public health system has a well-established process for developing new flu vaccines, based on monitoring circulating flu strains in the lead-up to flu seasons in different parts of the world. Eventually, we will likely get to a similar place with COVID-19 (if annual vaccines become necessary! also an open question at the moment). But right now, the waxing and waning of surges caused by new variants and human behavior makes it difficult to identify the actual seasonality of COVID-19.

- At what point do we say the vaccine isn’t working well enough? This question was asked by VRBPAC committee member Cody Meissner of Tufts University, during the discussion portion of the meeting. So far, the most common way to measure COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in the lab is by testing antibodies generated by a vaccine against different forms of the coronavirus. But these studies don’t account for other parts of the immune system, like T cells, that garner more long-term protection than antibodies. We need a unified method for measuring vaccine effectiveness that takes different parts of the immune system into account, along with real-world data.

- How might vaccine safety change over time? This question was brought up by Hayley Ganz of Stanford, another VRBPAC committee member. The CDC does have an extensive system for monitoring vaccine safety; data from that system should be readily available to the experts making booster shot decisions.

Another thing I’m wondering about right now, personally, is how the U.S.’s shifting focus away from case data might make all of this more complicated. As public health agencies scale down case investigations and contact tracing—and more people test positive on at-home, rapid tests that are never reported to these agencies—we’re losing track of how many Americans are actually getting COVID-19. And breakthrough cases, which are more likely to be mild or asymptomatic, might also be more likely to go unreported.

So, how does the U.S. public health system study vaccine effectiveness in a comprehensive way if we simply aren’t logging many of our cases? Programs such as randomized surveillance testing and cohort studies might help, but outside of a few articles and Twitter conversations, I’m not seeing much discussion of these solutions.

Finally: a few friends and relatives over age 50 have asked me about when (or whether) to get another booster shot, given all of the uncertainties I laid out above. If you’re in the same position, here are a couple of resources that might help:

- Fourth Dose Q&A (Your Local Epidemiologist)

- How to Time Your Second Booster (The Atlantic)

- Do I really need another booster? The answer depends on age, risk and timing (NPR)

More vaccine data

-

Sources and updates, March 27

- New report on pandemic-related workplace violence for public health officials: A new study, published last week in the American Journal of Public Health, shares the results of a survey that included hundreds of public health officials across the U.S. During the study’s time frame (March 2020 to January 2021), the researchers identified about 1,500 instances of harassment against public health officials, and found that over 200 officials left their jobs. And public health has only become more polarized in the year since this survey period ended. See this article in STAT News for more context on the study.

- Health insurance plans available through the federal insurance marketplace: This one isn’t directly COVID-related, but it seemed like an interesting data source to share: the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) publishes a series of data files on health insurance plans available through the federal Health Insurance Exchange. The files include health benefits, coverage limits, cost-sharing potential, provider networks, anonymized insurance claims, and much more. (H/t Data Is Plural.)

- At-home COVID-19 test use exacerbates inequities: This week, the CDC published a new MMWR study discussing rapid at-home test use. The authors used an online survey to estimate at-home test use among about 400,000 U.S. adults between August 2021 and early March 2022. Its findings provide additional evidence for the popularity of these tests during the Omicron surge, as well as for the way that these tests exacerbate health inequities in the U.S.: “at-home test use was lower among persons who self-identified as Black, were aged ≥75 years, had lower incomes, and had a high school level education or less,” the authors reported.

- Considering another round of mRNA booster shots: Will the U.S. authorize a fourth round of shots for Americans who received the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines? At the moment, signs point to yes: countries like Israel and the U.K., which U.S. regulators watch for their vaccine efficacy data, are providing fourth doses to seniors. And the Biden administration is planning fourth doses for U.S. adults over age 50, the New York Times reported on Friday. Data so far suggest that these additional doses may be useful for older adults, but provide less of an immunity boost in younger age groups; Dr. Katelyn Jetelina’s Your Local Epidemiologist post on the subject provides a helpful overview of the evidence.

- New data on Moderna vaccine for young children: As we consider additional boosters for seniors, the youngest Americans may soon be eligible for vaccination! Finally! After a lot of back-and-forth on the potential of Pfizer’s vaccine for kids under age five, Moderna released data this week suggesting that the company has found a dosage of its vaccine that significantly reduces the risk of severe COVID-19 symptoms for children between six months and six years old. Effectiveness against any symptomatic coronavirus infection was only about 40% in this trial—but that result is in line with vaccine efficacy for adults during the Omicron wave, when Moderna’s trial was conducted.

-

Omicron updates: BA.2, vaccine effectiveness, and more

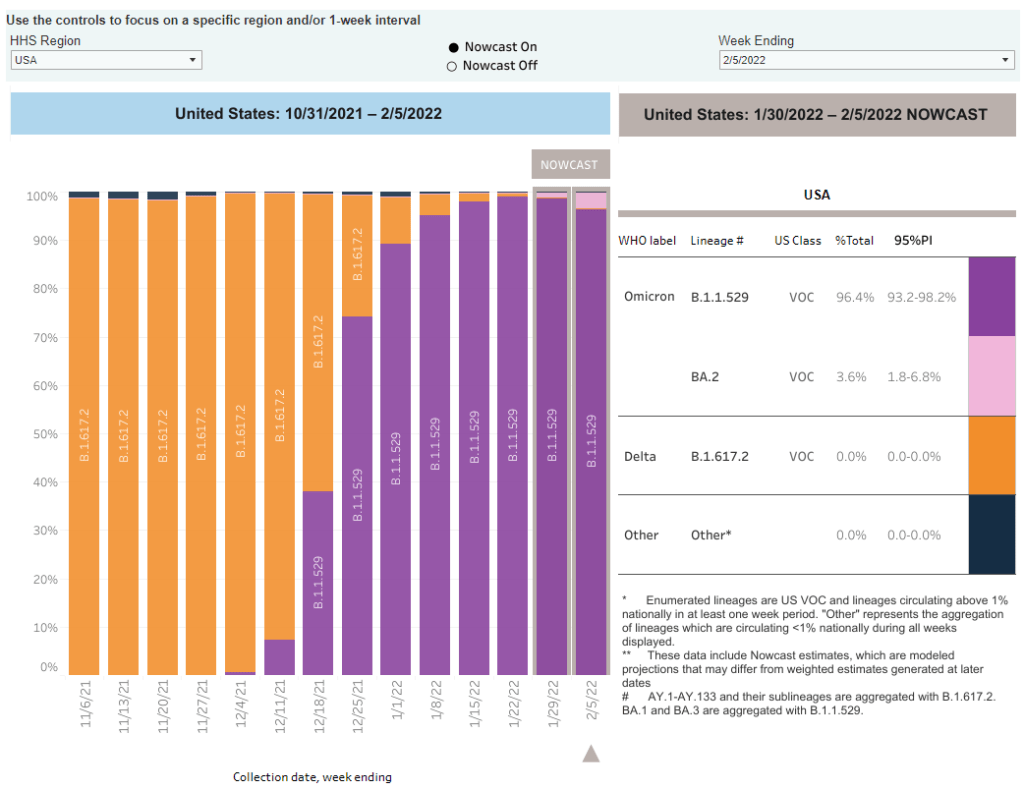

As of February 5, the CDC is now including BA.2 in its variant prevalence estimates. Screenshot from the CDC dashboard. A few Omicron-related news items for this week:

- The CDC added BA.2 to its variant prevalence estimates. As I mentioned in today’s National Numbers post, the CDC is now splitting out its estimates of Omicron prevalence in the U.S. into original Omicron, also called B.1.1.529 or BA.1, and BA.2—a sister strain that’s capable of spreading faster than original Omicron. BA.2 has become the dominant variant in some parts of Europe and Asia, but seems to be present in the U.S. in fairly low numbers so far: the CDC estimates it caused about 3.6% of new cases nationwide in the week ending February 5, with a 95% confidence interval of 1.8% to 6.8%. The remainder of new cases last week were caused by original Omicron.

- CDC describes its expanded genomic surveillance efforts in an MMWR study released this week. Between June 2021 and January 2022, the agency has extended its ability to monitor new variants spreading in the U.S., incorporating public repositories like GISAID into CDC data collection and developing modeling techniques that can produce more timely estimates of variant prevalence. (Remember: all variant data are weeks old, so the CDC uses modeling to predict the present.) According to the MMWR study, genomic sequencing capacity in the U.S. tripled from early 2021 to the second half of the year.

- Vaccine effectiveness from a booster shot wanes several months after vaccination. In another MMWR study released this week, the CDC reports on mRNA vaccine effectiveness after two and three doses, based on data from a hospital network including hundreds of thousands of patients in 10 states. During the U.S.’s Omicron surge, researchers found, vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 hospitalization was 91% two months after a third dose—but declined to 78% four months afterward. It’s unclear whether this declining effectiveness is a direct result of Omicron getting past the vaccine’s defenses, or whether we’d see similar declines with other variants. Also, the CDC’s findings are not stratified by age or other factors that make people more vulnerable to severe COVID-19.

- Updated monoclonal antibody treatment from Eli Lilly gets FDA authorization. During the Omicron surge, one challenge for healthcare providers has been that, out of three monoclonal antibody treatments authorized by the FDA, only one retained effectiveness against this variant. (Monoclonal antibody treatments provide a boost to the immune system for vulnerable patients.) This week, however, the FDA authorized an updated version of Eli Lilly’s treatment that does work against Omicron, including against the BA.2 lineage. The federal government has purchased 600,000 courses of this new treatment.

- More data released on South Africa’s mild Omicron wave. A new paper published in JAMA this week, from researchers at a healthcare provider in South Africa, compares COVID-19 hospitalizations during the Omicron surge to past surges. Among patients who visited the 49 hospitals in this provider’s network, about 41% of those who went to an emergency department with a positive COVID-19 test were admitted to the hospital during the Omicron surge—compared to almost 70% during South Africa’s prior surges. The paper provides additional evidence that Omicron is less likely to cause severe COVID-19 than past variants, though this likelihood is tied in part to high levels of vaccination and past infection in South Africa and other countries.

- Omicron has been identified in white-tailed deer. New York City was an early Omicron hotspot in the U.S.; and the variant has been passed onto white-tailed deer in Staten Island, according to a new preprint posted this week (and not yet peer-reviewed). Scientists have previously identified coronavirus infections in 13 states, but finding Omicron is particularly concerning for researchers. “The circulation of the virus in deer provides opportunities for it to adapt and evolve,” Vivek Kapur, a veterinary microbiologist who was involved in the Staten Island study, told the New York Times.

More variant reporting

-

Omicron updates: The continued importance of vaccination

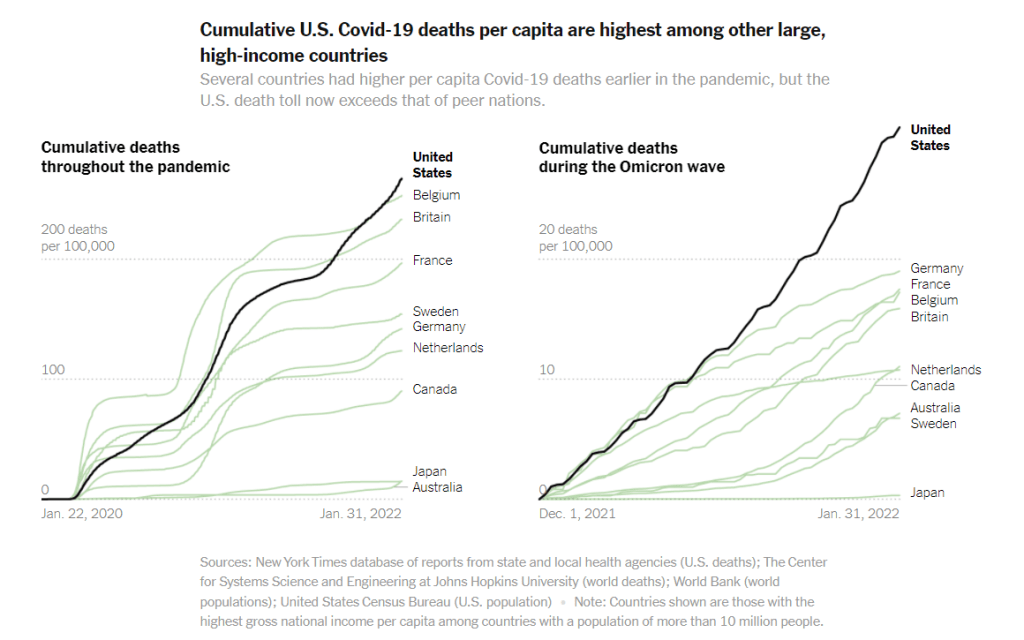

COVID-19 deaths during the Omicron wave have been much higher in the U.S. than in other similarly wealthy countries, according to a New York Times analysis. Just a few updates for this week:

- Scientists are still learning about BA.2, the more-transmissible Omicron offshoot. There haven’t been many major updates about BA.2 since last week, when I wrote this FAQ post; but this STAT News article by Andrew Joseph provides a helpful summary of what we know so far. The article explains that BA.2 clearly has a transmission advantage over BA.1 (and has now become the dominant variant in a few countries), but BA.1 may have spread around the world due to chance and some well-placed superspreading events. Notably, the CDC is not yet splitting out its Omicron prevalence estimates into BA.1 and BA.2, so we don’t have a great sense of how much this sub-lineage is spreading in the U.S.

- More data indicates immune system memory remains strong against Omicron. In previous Omicron update posts, I’ve noted that, while vaccinated people are more likely to have a breakthrough case with Omicron than with past variants, vaccination is still highly protective against severe symptoms. A new study published in Nature this week further affirms this protection; researchers found that 70% to 80% of T cell response to Omicron was retained in people who were vaccinated or tested positive on antibody tests, compared to past variants. (T cells are key pieces of immune system memory response.)

- Similarly, more data backs up the importance of vaccination to protect against severe disease during the Omicron era. The CDC released more MMWR studies this week showing that fully vaccinated and boosted Americans were less likely to require hospitalization or intensive care during the Omicron surge compared to the unvaccinated. For example, in Los Angeles County, California, hospitalization rates among unvaccinated people were 23 times higher than rates among those fully vaccinated with a booster, and five times higher than those vaccinated without a booster.

- Omicron is too transmissible for school testing programs to keep up. I’ve previously reported on the challenges of K-12 COVID-19 testing programs, including the difficulty of setting up public health logistics, getting enough tests, and increasing polarization of testing. During the Omicron surge, these challenges have been magnified—to the point that some states, including Utah, Vermont, and Massachusetts, have suspended testing programs, POLITICO reported this week. I hope to see some of these programs resume after the surge is over.

- The U.S.’s death toll during the Omicron surge has been far higher than in similarly wealthy nations. A new analysis from the New York Times compares the death toll in the U.S. from December 2021 through January 2022, adjusted for population, to death tolls in peer wealthy nations like Germany, Canada, Australia, and Japan. The comparison is striking: “the share of Americans who have been killed by the coronavirus is at least 63 percent higher than in any of these other large, wealthy nations,” the NYT reports. This difference is largely because the U.S. is less vaccinated than these other countries, particularly when it comes to booster shots and vaccinations among seniors.

- Globally, cases during the Omicron surge surpassed all of 2020. “In the 10 weeks since Omicron was discovered, there have been 90 million COVID-19 cases reported — more than in all of 2020,” said Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organization, at a press conference last week. In a Twitter thread reporting from the press conference, STAT’s Helen Branswell noted that the WHO is concerned about countries “opening up” and lifting COVID-19 restrictions before their case numbers are actually low enough to warrant these measures.

More variant reporting

-

Featured sources, January 9

- COVID-19 Hospital Capacity Circuit Breaker Dashboard: This dashboard from emergency physician Dr. Jeremy Faust and colleagues shows which U.S. states and counties are operating at unsustainable levels, or are likely to get there in coming days. Faust further explains circuit breakers in this post: these are “short-term restrictions, regardless of vaccination status, designed to slow the spread of COVID-19” and help prevent hospitals from becoming overwhelmed. Dashboard data come from the CDC, HHS, and Johns Hopkins University.

- CDC Cruise Ship Color Status: Throughout the pandemic, cruise ships have been hotbeds for coronavirus spread. This is especially true right now, thanks to Omicron, and the CDC is investigating a number of outbreaks. The agency reports on all cruise ships that it’s monitoring for COVID-19, classifying them based on the number of cases reported among passengers and crew; as of January 7, the vast majority of ships have reported enough cases to meet the threshold for CDC investigation.

- Deaths and hospitalizations averted by vaccines: This December report from philanthropy foundation the Commonwealth Fund provides estimates on the severe COVID-19 cases prevented by the U.S. vaccination effort. Without vaccination, the report estimates, “there would have been approximately 1.1 million additional COVID-19 deaths and more than 10.3 million additional COVID-19 hospitalizations in the U.S. by November 2021.” (H/t Your Local Epidemiologist.)

-

Sources and updates, November 28

- State vaccination data: This weekend, I updated my annotations on state and national vaccination data sources in the U.S. A few more states are now reporting information on booster shots, and several states have adjusted their vaccine coverage metrics to reflect vaccine eligibility for children in the 5 to 11 age group. Notably, since my last update, Alaska, D.C., Utah, and Vermont’s health agencies have all started reporting some demographic information regarding booster shot recipients in their states.

- Moral injury among healthcare workers during COVID-19: There have been a lot of headlines recently about burnout among healthcare workers. This study, based on a survey of 1,300 healthcare workers and published this week in JAMA Network Open, provides some statistics to underlie the trend. See the supplemental materials for sample quotations from the survey respondents, demonstrating their feelings of fatigue, isolation, and betrayal.

-

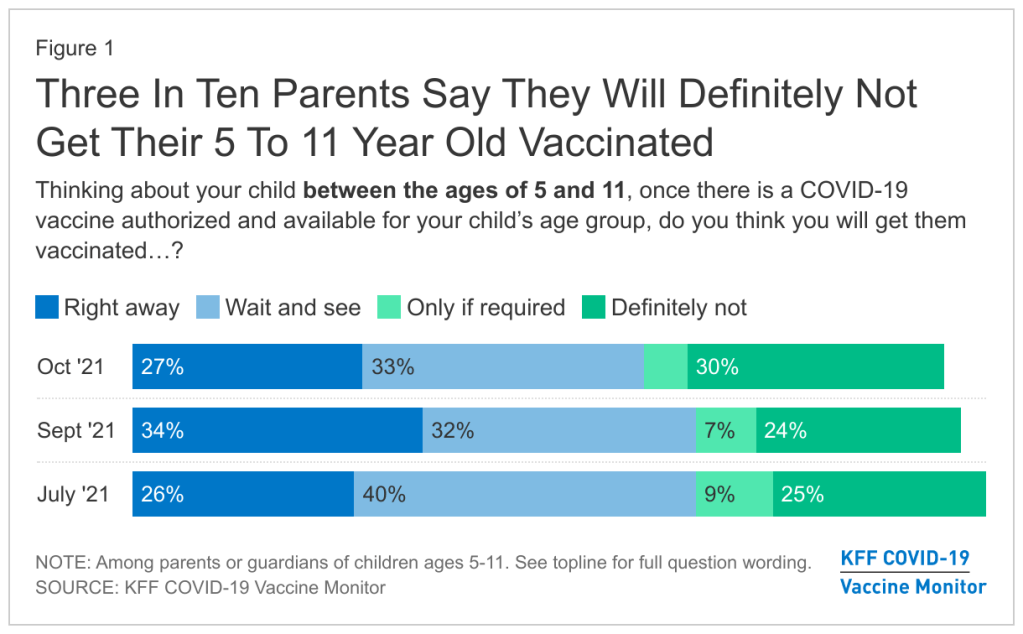

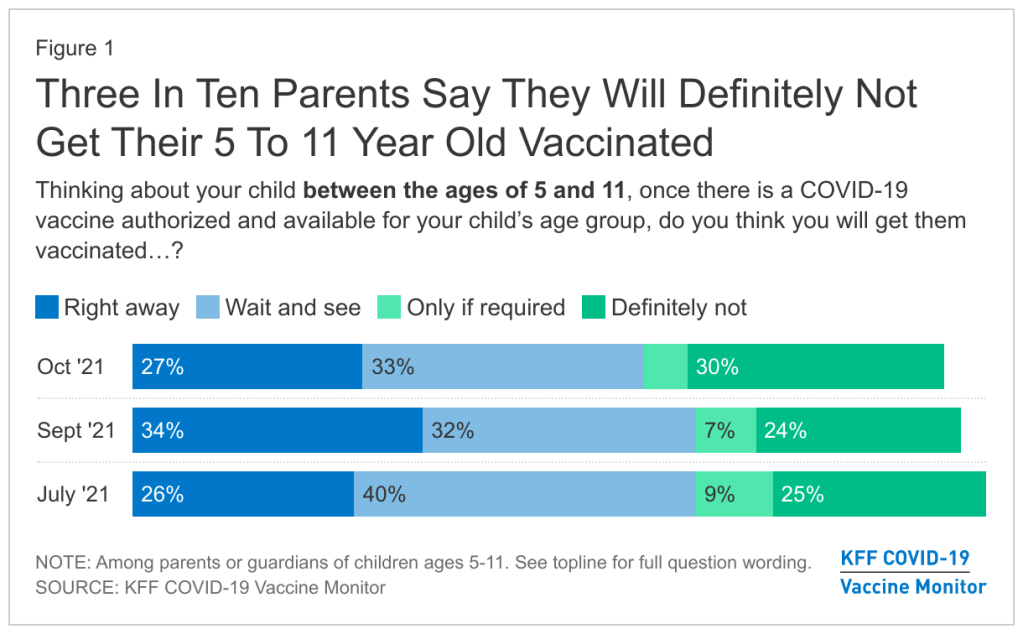

FDA authorizes Pfizer vaccine for younger children

The Pfizer vaccine will likely be available to children ages 5 to 11 next week, but many parents are hesitant about getting their kids vaccinated. Chart via the KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor. Last week, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine for children ages 5 to 11, under an Emergency Use Authorization. The agency’s vaccine advisory committee met on Tuesday to discuss Pfizer’s application and voted overwhelmingly in favor; the FDA followed this up with an EUA announcement on Friday.

This coming week, the process continues: CDC’s own vaccine advisory committee will discuss and vote on vaccinating kids in the 5-11 age group, and then the agency will make an official decision. If all goes well—and all is expected to go well—younger kids will be able to get their vaccines in time for Thanksgiving.

Many of the parents I know have been eagerly awaiting this authorization, but the sentiment is far from universal. COVID-19 vaccinations for kids are incredibly controversial, more so than vaccinations for adults. The public comment section of the FDA advisory committee meeting—in which basically anyone can apply to share their thoughts—was full of anti-vaxxers, many of them sharing misinformation. Even some experts on the FDA advisory committee were not fully convinced that vaccines are needed for all young kids, though all but one eventually voted in favor.

Now, let me be clear: there are definite benefits to vaccinating younger children. While kids are less likely to have severe COVID-19 cases than adults, the disease has still been devastating for many children. Almost 100 kids in the 5 to 11 age range have died of COVID-19, making this disease one of the top 10 causes of death for this group over the past year and a half.

Plus, children who get infected with the coronavirus are at risk for Long COVID and MIS-C, two conditions with long-lasting ramifications. There have been about 5,200 MIS-C cases thus far—and the majority of these cases have occurred in Black and Hispanic/Latino children. Minority children are also at much higher risk for COVID-19 hospitalization.

Vaccination can prevent children from severe ramifications of a potential COVID-19 case, as well as from the mild infections that lead to missed school and other disruptions. But the FDA committee had to carefully weigh this benefit against potential side effects from vaccination, namely myocarditis—a type of heart inflammation.

The U.S. system for tracking vaccine side effects has identified a small number of myocarditis cases in children ages 12 to 15 after their second shots of Pfizer or Moderna vaccines. For the meeting this past Tuesday, the FDA presented some models weighing potential myocarditis cases in young kids against vaccination benefits; the models showed that, in almost every scenario, the number of severe COVID-19 cases prevented by vaccination is higher than the myocarditis cases.

It’s worth noting: in Pfizer’s clinical trial for the 5 to 11 age group, no child had a severe adverse reaction to the vaccine. But the Pfizer researchers did observe five medical events that were unrelated to vaccination—including one kid who swallowed a penny.

Some of the FDA advisory committee members suggested that perhaps vaccines would be most beneficial for children with underlying medical conditions, who are more susceptible to severe COVID-19. But the committee ultimately voted in favor of vaccines for all kids in the 5 to 11 age group, allowing parents to consult their pediatricians and pursue vaccination if they deem it necessary.

Polling data suggest that many parents don’t currently deem it necessary, though. The latest survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that just 27% of parents with kids in the 5 to 11 age range plan to get their kids vaccinated immediately, once shots are available. 33% intend to “wait and see,” 5% will only pursue vaccination if it’s required by the child’s school, and 30% say “definitely not.”

Public health experts, pediatricians, and others in the science communication world have a lot of work ahead of us to convey the importance of vaccinating kids—and dispel misinformation.

Note: this post relies heavily on STAT News’s liveblog of the FDA committee meeting.

More vaccine coverage

-

Featured sources, October 10

- COVID-19 Vaccine Effectiveness (CDC): The CDC has added a new page to its COVID Data Tracker, focused on visualizing how well the vaccines work. This page includes data from several ongoing studies used by the CDC to monitor vaccine effectiveness: one tracks COVID-19 infection in long-term care facility residents, another tracks hospitalization in veterans, and so on. “This is not a comprehensive representation of all data sets, but the populations being followed are large and well described (if limited),” said science writer Katherine Wu, sharing the new page on Twitter.

- COVID-19-Associated Orphanhood in the U.S.: Over 140,000 American children lost a parent or a caregiver during the pandemic, according to a new study from the CDC, Imperial College London, and other collaborators. This study follows another study from Imperial College London that took a global focus (which I featured in the July 25 issue); this new paper includes data broken out by state and by race and ethnicity. Black children were more than twice as likely to lose a parent or caregiver as white children, and Native American children were more than four times as likely.