This week, the White House announced that it’s setting up a $5 billion program to support next-generation COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. The program, called Project Next Gen, is essentially a follow-up to Operation Warp Speed (which launched our current COVID-19 vaccines in 2020).

Project Next Gen is a big step toward actually ending the pandemic, not just pretending it’s over. The federal government can support large-scale clinical trials and speed up regulatory approval in a way that no research group or company could. Still, the U.S.’s prior vaccine campaigns don’t inspire confidence that this project will lead to widespread adoption of new shots when they become available.

What are the “next-gen” vaccines under development?

Next-gen COVID-19 vaccines generally fall into two categories: nasal vaccines that would provide better protection against infection, and pan-coronavirus vaccines that would provide better protection against new variants.

Nasal vaccines basically deliver immunity with a spray into the nose, rather than a shot in the arm. This type of vaccine already exists for other common viruses, like the flu. They’re easier to receive for people wary of needles, but they also have a big advantage for the immune system: these vaccines boost immunity in the nose, mouth, and upper respiratory tract, which are the main places where the coronavirus typically infects people. With a nasal vaccine’s help, the immune system is better poised to fight off the virus at infection, rather than fighting off severe symptoms after someone is already infected.

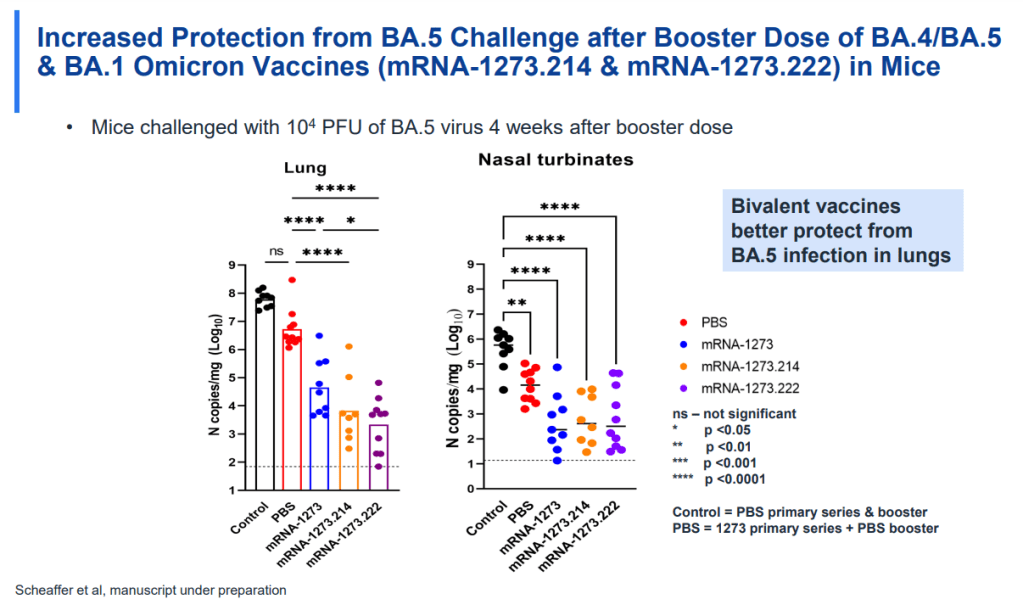

Pan-coronavirus vaccines, meanwhile, address the variant challenge. Our current COVID-19 vaccines are designed around the virus’ spike protein, a component on the outside of the virus that helps it break into human cells. But the spike protein is the primary area where the coronavirus mutates; the spike proteins of XBB.1.5.1 or XBB.1.16 are very different from that of the original virus. New pan-virus vaccine candidates are designed around different aspects of the virus that don’t mutate as much, and therefore would remain more protective against new variants.

For more details on why these vaccine options are important and which candidates are now in the pipeline, I recommend reading this Substack post by Eric Topol, the prominent COVID-19 commentator and director of the Scripps Translational Research Institute. Topol has been calling on the Biden administration to support next-generation vaccines for a long time; he’s written extensively on this subject.

Why is a federal program important to advance these vaccines?

Operation Warp Speed was a monumental achievement, probably the most successful aspect of the U.S.’s response to COVID-19. The federal government provided significant funding to pharmaceutical companies, while also assisting with clinical trial development and facilitating collaboration between companies and the FDA. And the first mRNA vaccines were delivered within one year of the pandemic starting.

Project Next Gen will provide a similar boost to the companies working on next-gen vaccines. It’s not going to operate at the same scale as Operation Warp Speed; it received $5 billion in funding, compared to Warp Speed’s $18 billion. Still, that’s a huge chunk of money for companies, and other types of federal support that will be crucial for quickly starting up large clinical trials.

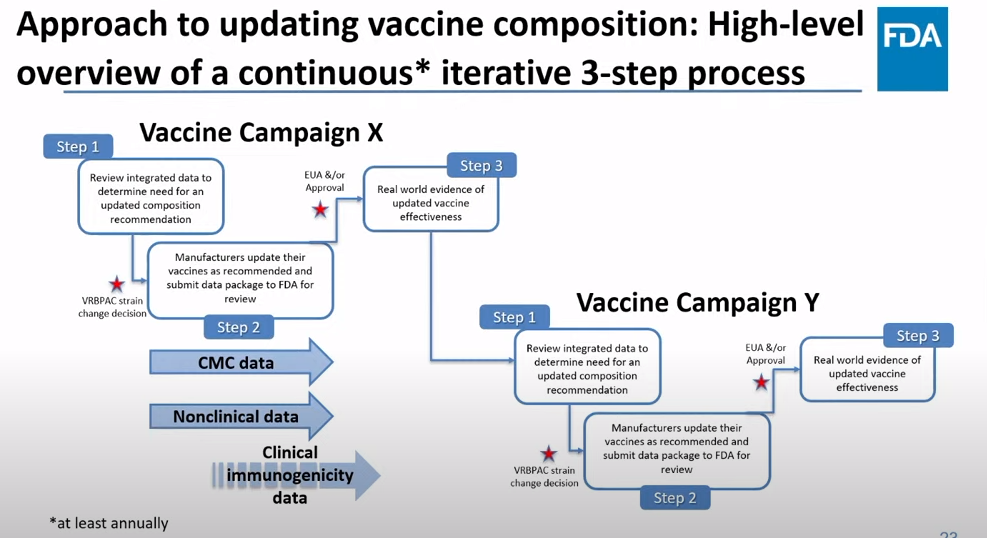

The White House is currently assessing pharmaceutical companies that it may partner with on this initiative, according to reporting by the Washington Post. There’s no clear timeline for Project Next Gen yet, as the government will need to work with specific companies and the FDA to plan trials, but it’ll certainly be much faster than these vaccines would get to people otherwise.

What are the challenges facing Project Next Gen?

While this initiative is great news, its implementation will face a lot of challenges—especially after the new vaccines become available. The federal government’s rhetoric around COVID-19, combined with our now-mostly-dismantled infrastructure for responding to the disease, will present major barriers to getting people vaccinated.

For example, it’s obviously very ironic that the Project Next Gen announcement came in the same week as Biden signed a bill ending one of the federal COVID-19 emergencies. And the timing isn’t just coincidental: the White House and HHS are actually using the emergency’s end to fund this project, moving in money that was previously devoted to COVID-19 testing and other preventative measures.

The administration is basically telling people: “COVID-19 is over, but uh, we might need you to get a new vaccine or two next year so that you don’t die from it.” It’s hard to blame people for not getting the second part of the message.

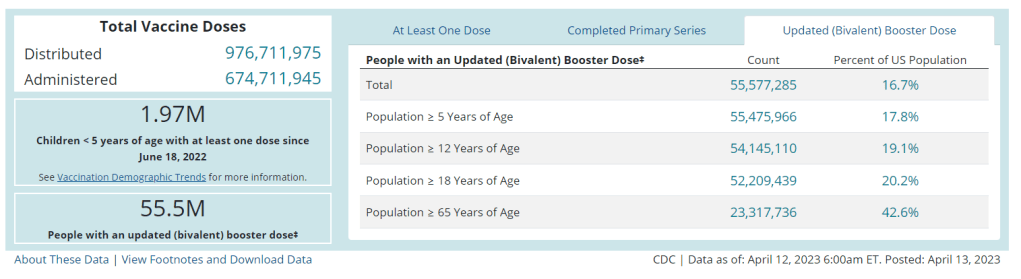

We’re already seeing this with the Omicron boosters: only 17% of the U.S. population has received one, according to CDC data. Lack of awareness about those vaccines and the many barriers that now exist to get the shots contributed to that low number. Even if Project Next Gen delivers the most effective COVID-19 vaccines possible, a lot more investment would be necessary to actually get them to people.