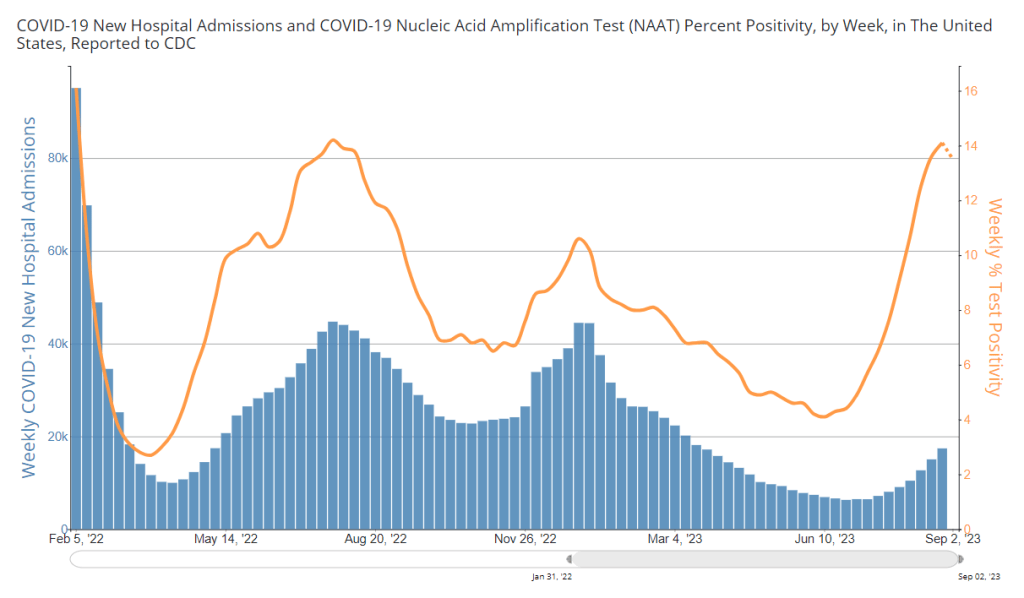

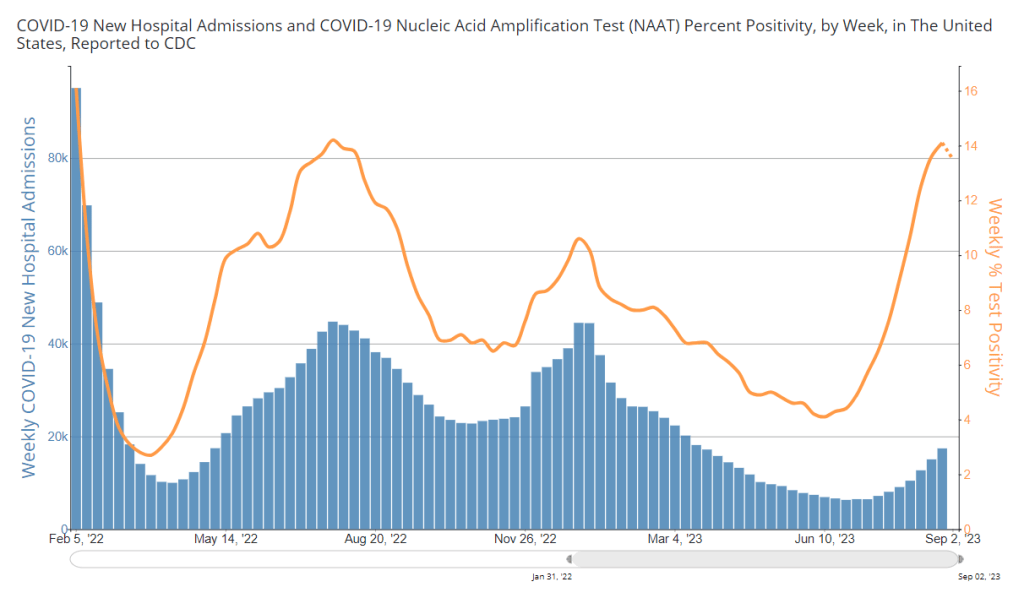

During the most recent week of data available (August 20-26), the U.S. reported about 17,400 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 2,500 new admissions each day

- 5.3 total admissions for every 100,000 Americans

- 16% more new admissions than the prior week (August 13-19)

Additionally, the U.S. reported:

- 13.5% of tests in the CDC’s surveillance network came back positive

- A 0.3% higher concentration of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater than last week (as of September 6, per Biobot’s dashboard)

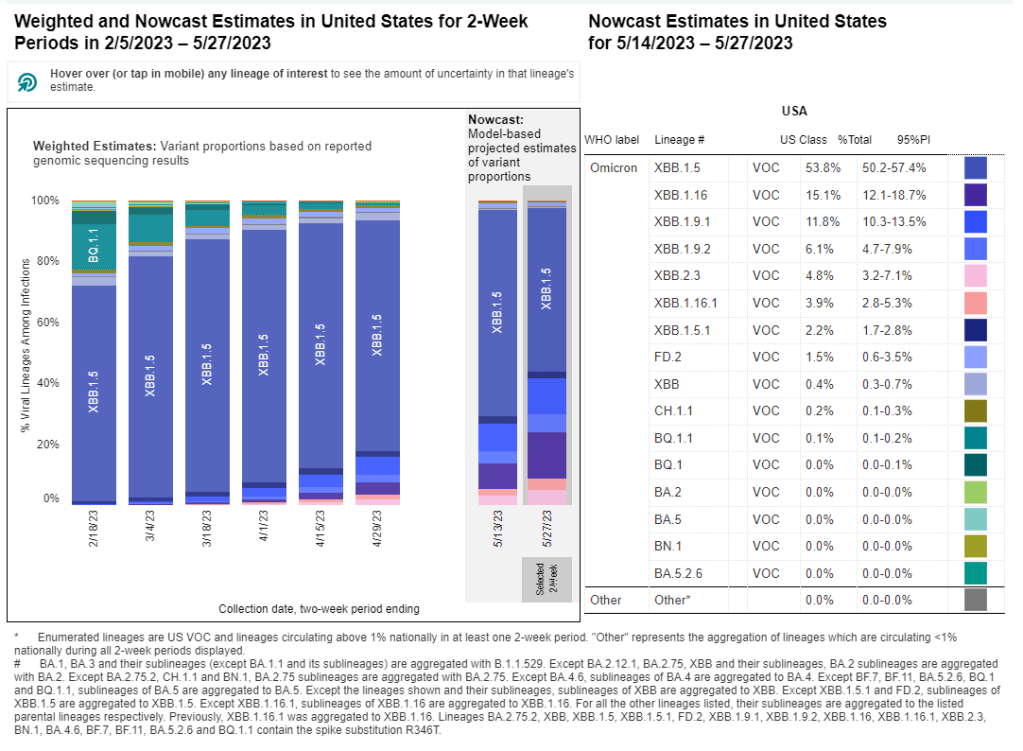

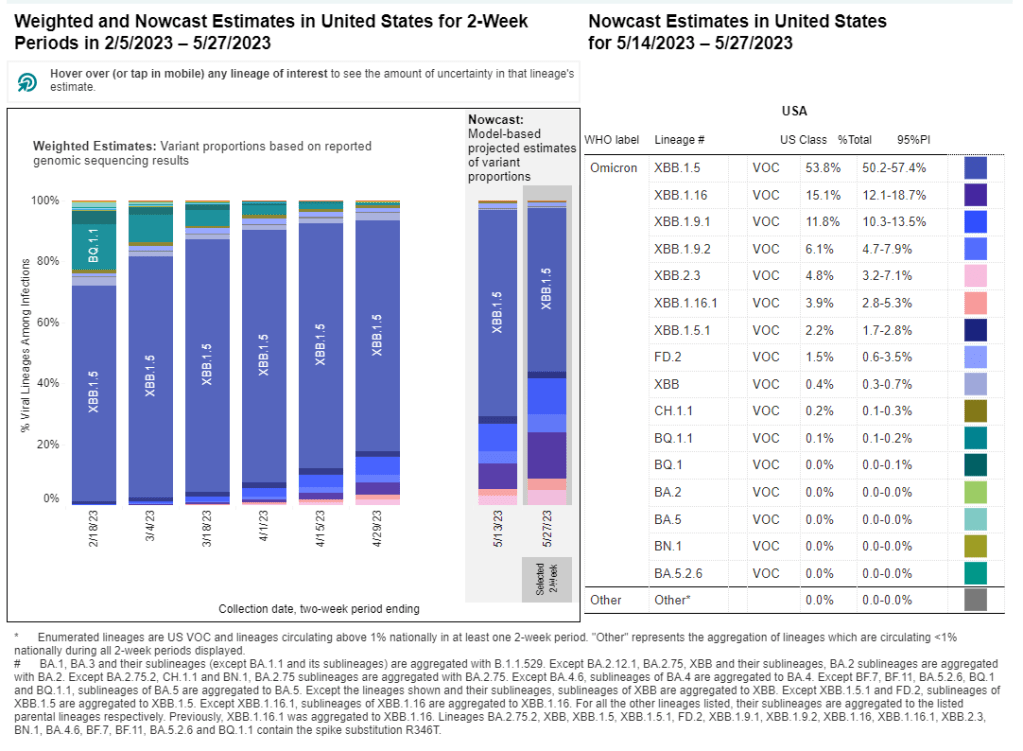

- 23% of new cases are caused by Omicron XBB.1.6; 22% by EG.5; 15% by FL.1.5.1 (as of September 2)

After two months of consistent increases in major COVID-19 metrics, we have once again reached, “Has the surge peaked?” territory. Preliminary data from wastewater and testing are suggesting potential plateaus, while more people are still getting hospitalized with COVID-19.

National trends from Biobot Analytics’ wastewater surveillance network show very similar coronavirus levels in sewage this week and last week: 641 virus copies per milliliter of sewage on September 6, compared to 639 on August 30. These data are preliminary, though, and could change as more sewersheds report.

Biobot’s regional data suggest different trends in different parts of the country: the South and West coast might be turning around, the Northeast is still reporting an increase (but the speed of increase there is slowing), and the Midwest is reporting a sharp increase following a recent decrease.

Data from the CDC network and WastewaterSCAN similarly show mixed results depending on your location. Among CDC sites with recent data, about half reported increased coronavirus in their wastewater in the last two weeks, while the other half reported decreases. WastewaterSCAN’s network reports continued increases in Midwestern states, including sewersheds in Michigan, Ohio, and Kansas.

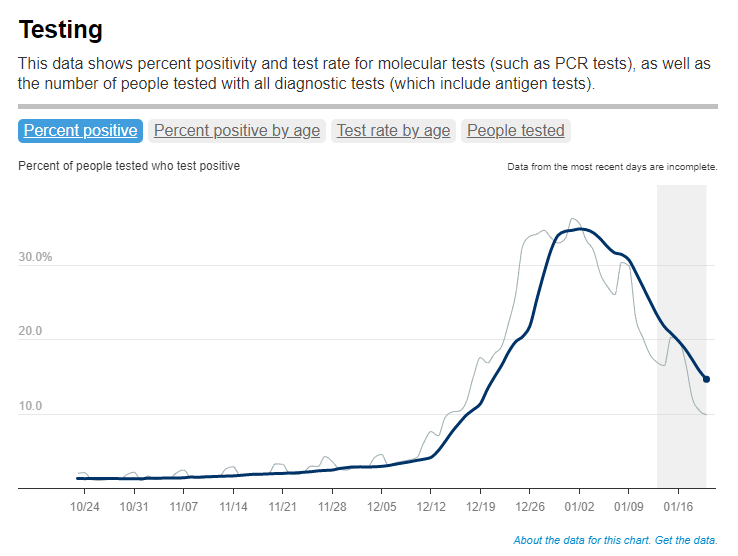

Test positivity data from the CDC’s respiratory surveillance network also indicate that the summer surge might have peaked, or at least might be slowing. For the first time in several weeks, test positivity decreased slightly in the most recent CDC update, from 14.1% in the week ending August 26 to 13.5% in the week ending September 2.

Walgreens’ COVID-19 positivity tracker (which shares data from tests conducted by the pharmacy network) reported a slight decrease as well, from 43.6% in the week ending August 26 to 40.6% in the week ending September 2. Like the wastewater surveillance data, this information is preliminary but could be a good sign.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 hospitalizations—a more delayed metric—are still increasing. About 2,500 people were newly hospitalized with COVID-19 each day in the week ending August 26. Hospitalizations have particularly gone up for older adults, according to data from insurance company Humana shared with STAT News.

Many students went back to school last week, as the fall semester gets underway. This could be another driver of COVID-19 spread, as travel and gatherings were in the summer. Better air quality, masks, and other measures could make schools safer for students, teachers, staff, and their families.