I’m doing another post dedicated to Long COVID research this week, unpacking a noteworthy new data source. Also, I have an update about a Long COVID study that I shared in last week’s issue.

First: new data from the Household Pulse Survey suggests that almost 20% of Americans who got COVID-19 are currently experiencing Long COVID symptoms. The Household Pulse Survey is a long-running Census project that provides data on how the pandemic has impacted Americans, with questions ranging from job loss to healthcare access.

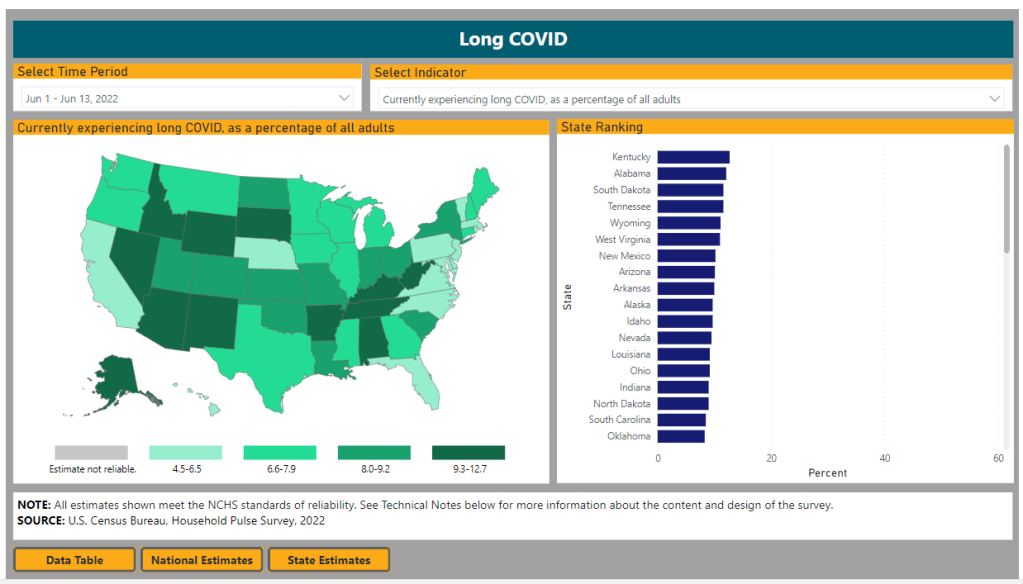

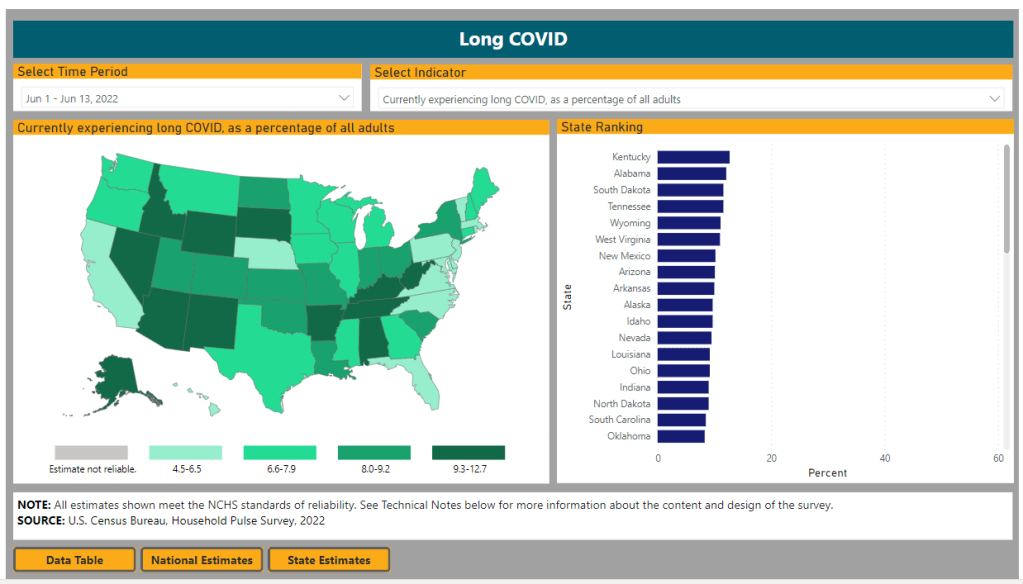

In the most recent iteration of this survey, which started on June 1, the Census is asking respondents about Long COVID: specifically, respondents can share whether they had COVID-related symptoms that lasted three months or longer. The first round of data from this updated survey were released last week (representing respondents surveyed between June 1 and June 13), in a collaboration between the Census and the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

The numbers are staggering. Here are a few notable findings, sourced from the NCHS press release:

- An estimated 14% of all U.S. adults have experienced Long COVID symptoms at some point during the pandemic.

- About 7.5% of all U.S. adults are currently experiencing Long COVID symptoms, representing about one in 13 Americans.

- Out of U.S. adults who have ever had COVID-19, about 19% are currently experiencing Long COVID symptoms.

- Older adults are more likely to report Long COVID than younger adults, while women are more likely to report it than men.

- About 8.8% of Hispanic or Latino adults are currently experiencing Long COVID, compared to 6.8% of Black adults and 7.5% of White adults.

- Bisexual and transgender adults were more likely to report current Long COVID symptoms (12.1% and 14.9%, respectively) than those of other sexualities and genders.

- States with higher Long COVID prevalence included Southern states like Kentucky, Alabama, and Tennessee.

This study is a big deal. The Household Pulse Survey is basically the closest comparison that the U.S. has to the U.K.’s highly-lauded Office for National Statistics survey, in that the survey can collect comprehensive data from a representative subset of Americans and use it to provide national estimates.

In other words: two years into the pandemic, we finally have a viable estimate of how many people have Long COVID, and it is as large an estimate as Long COVID advocates warned us to expect. Plus, demographic data! State-by-state-data! This is incredibly valuable, moreso because the Household Pulse Survey will continue incorporating Long COVID into its questions.

Also, it’s important to note that Long COVID patients were involved in advocating for and shaping the new survey questions. Big thanks to the Patient-Led Research Collaborative and Body Politic for their contributions!

Next, two more Long COVID updates from the past week:

- Outcomes of coronavirus reinfection: A new paper from Ziyad Al-Aly and his team at the Veterans Affairs Saint Louis healthcare system, currently under review at Nature, explores the risks associated with a second coronavirus infection. They found that a second infection led to higher risk of mortality (from any cause), hospitalization, and specific health outcomes such as cardiovascular disorders and diabetes. “The risks were evident in those who were unvaccinated, had 1 shot, or 2 or more shots prior to the second infection,” the researchers wrote in their abstract.

- NIH data now available for Long COVID research: The National Institutes of Health’s “All of Us” research program is releasing a dataset from almost 20,000 people who have had COVID-19 for scientists to study. The data come from clinical records, genomic sequencing, and patient-reported metrics; researchers can use them to examine Long COVID trends, similarly to the way in which Al-Aly’s team uses VA records to study COVID-19 outcomes.

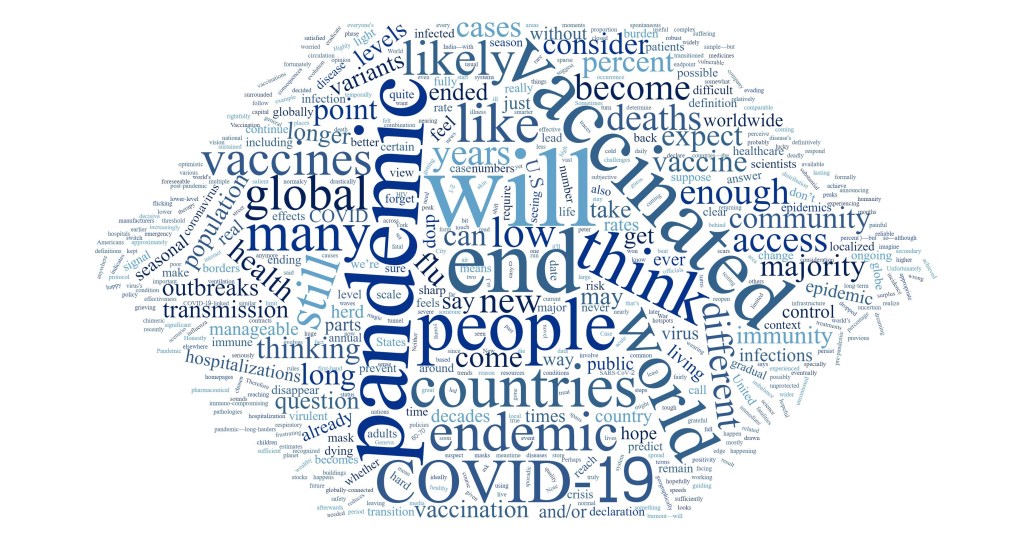

And finally, a correction: Last week, I shared a paper published in The Lancet which indicated Long COVID may be less likely after an Omicron infection compared to a Delta infection. A reader alerted me to some criticism of this study in the Long COVID community.

Specifically, the estimates in the paper are much lower than those found by the U.K.’s ONS survey, which is considered more reliable. This Lancet paper was based not on surveys but on a health app which relies on self-reported, volunteer data. In addition, the researchers failed to break out Long COVID risk by how many vaccine doses patients had received, which may be a key aspect of protection.

Finally, as I noted last week, even if the risk of Long COVID is lower after an Omicron infection, the risk is still there. And when millions of people are getting Omicron, a small share of Omicron infections leading to Long COVID still leads to millions of Long COVID cases.