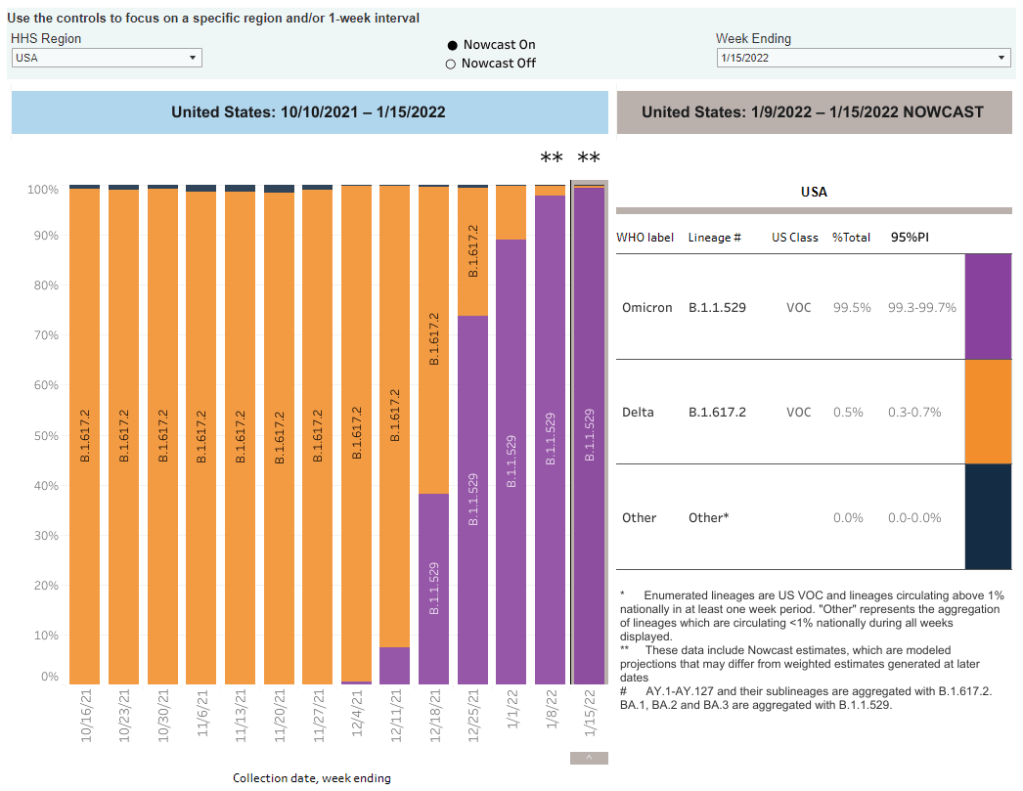

An offshoot strain of the Omicron variant has been making headlines this week as it spreads rapidly in some European and Asian countries. While the strain, called BA.2 by virologists, has not yet been identified in the U.S. in large numbers, it’s already spreading here, too: scientists have picked it up in wastewater samples in some parts of the country.

This strain clearly has a growth advantage over the original Omicron strain (also called BA.1), but it’s not cause for major concern at this point. Scientists are working to identify whether BA.2 has a higher capacity for breaking through immunity from past infection or vaccination; so far, early data suggest that it does not significantly differ from BA.1 on this front, though it may have a slight advantage.

Here’s a brief FAQ on what we know about the strain so far.

When and where did BA.2 emerge?

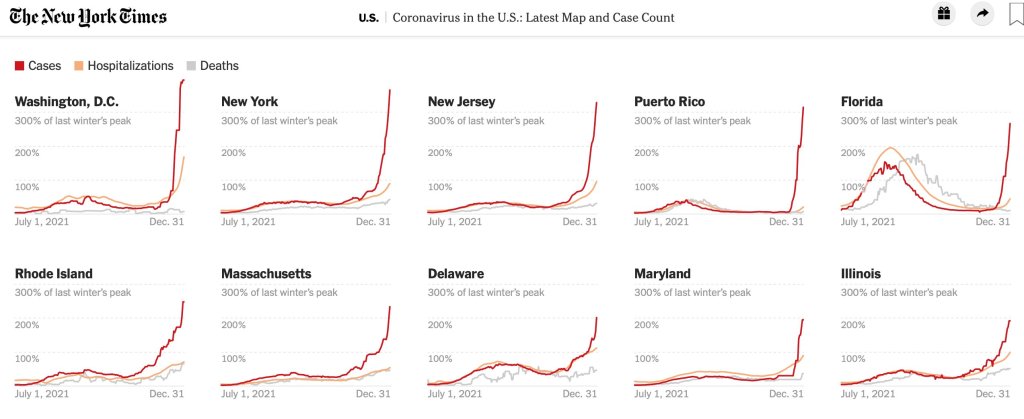

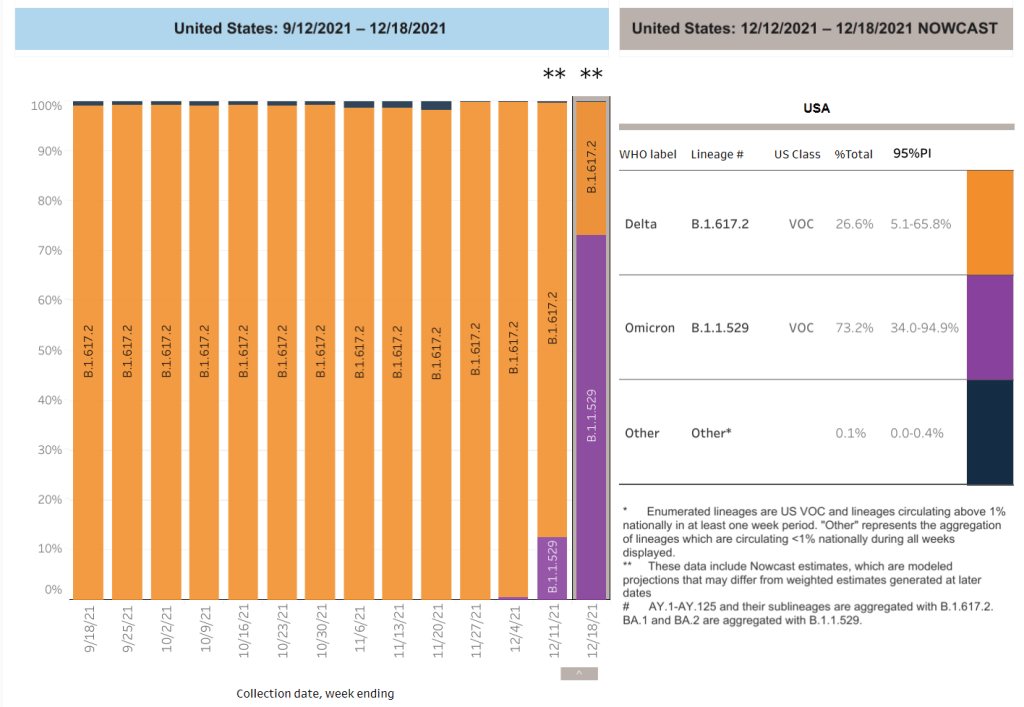

I’ve been careful not to call BA.2 a “new strain” or a “new variant” here because it’s not actually new—at least, it’s not any newer than Omicron BA.1. When South African scientists first sounded the alarm about Omicron in late November 2021, BA.2 was already present among the country’s cases of this variant.

In fact, a paper from South African scientists describing the Omicron wave in their country, published in Nature in early January, specifies that the earliest specimen of BA.2 was sampled on November 17; the earliest specimen of BA.1 was sampled on November 8. Around the same time, South African scientists also identified a third lineage, called BA.3—this one hasn’t yet become a cause for concern.

Why are scientists concerned about BA.2?

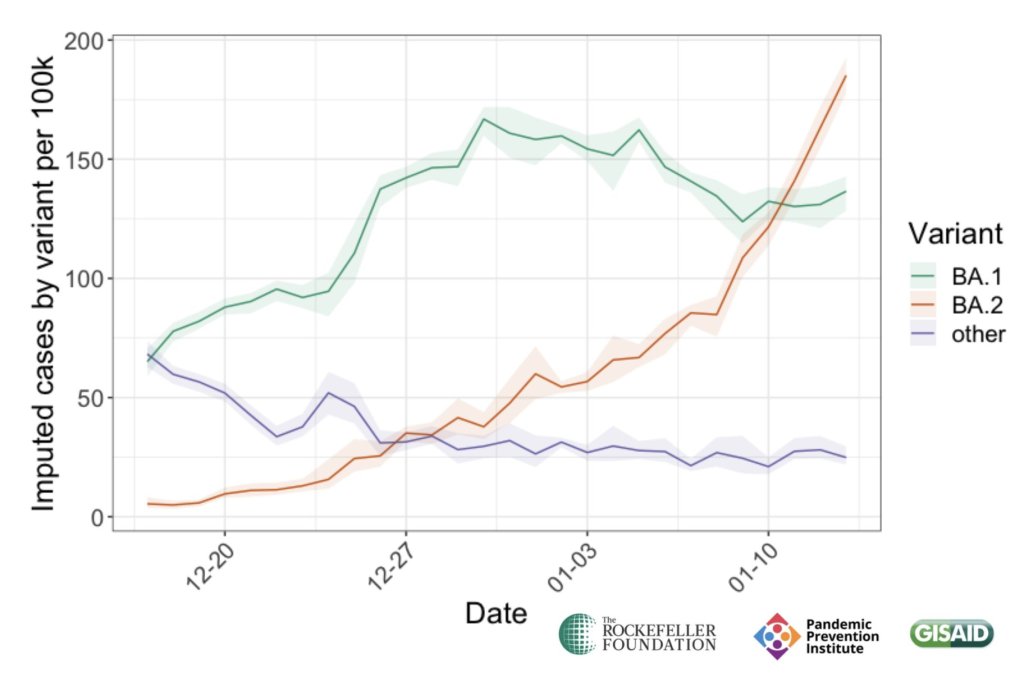

In the past couple of weeks, epidemiologists have identified that BA.2 is spreading faster in some countries than BA.1, the original Omicron strain. This means BA.2 has what scientists call a “transmission advantage” over BA.1: it is capable of getting from person to person fast enough that it may be able to outcompete BA.1.

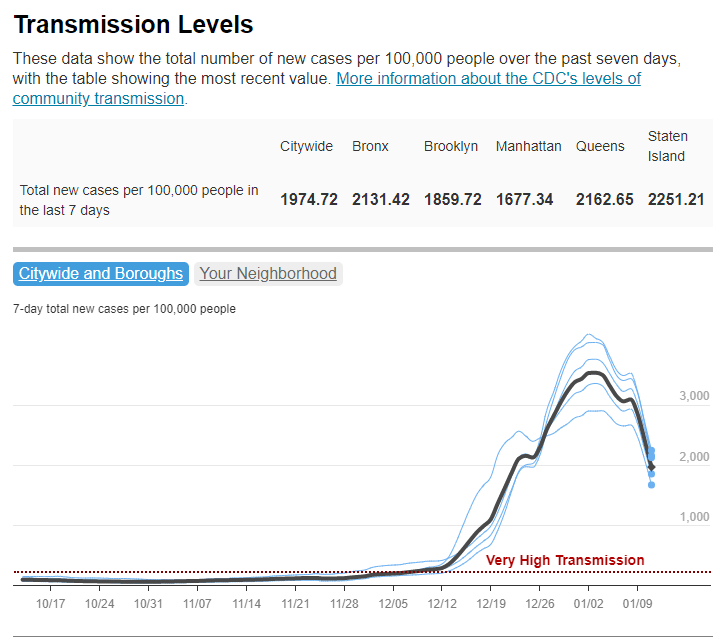

For example, in Denmark, BA.2 became the dominant strain in mid-January, taking over from BA.1. The takeover has coincided with an additional increase in COVID-19 cases in the country after Denmark’s Omicron wave initially appeared to peak a couple of weeks ago—but it’s hard to determine whether this second increase is solely due to BA.2 or also connected to an announcement that Denmark will end its COVID-19 restrictions on February 1.

This past week, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that investigations into BA.2, including its potential virulence and ability to escape prior immunity, “should be prioritized independently (and comparatively) to BA.1.” The WHO has yet to designate BA.2 as a separate variant of concern from BA.1, however; at the moment, both strains are still included under the Omicron label.

How does BA.2 compare to BA.1, the original Omicron strain?

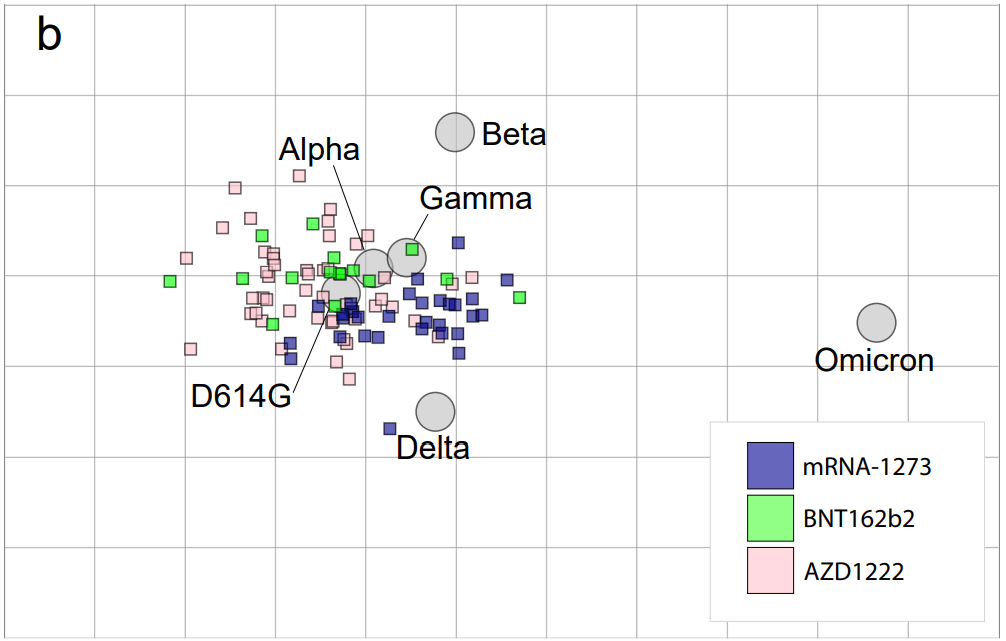

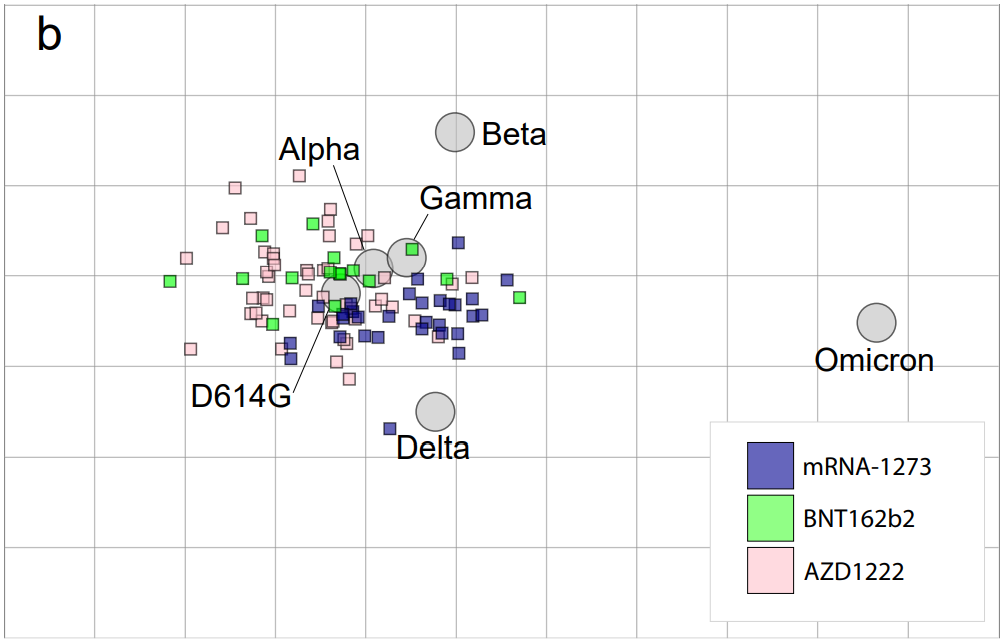

As I’ve explained in previous posts about the variant, Omicron has the most antigenic drift of any coronavirus variant identified thus far—meaning that it’s the most genetically different from the initial Wuhan version of the virus. Omicron BA.1 has about 60 mutations compared to the Wuhan strain, but BA.2 has even more: about 85 mutations, according to a recent Your Epidemiologist post.

BA.2 is clearly more transmissible than BA.1, as we’ve seen from its rapid spread in countries including Denmark, the U.K., France, the Netherlands, India, and the Philippines. Scientists estimate that “BA.2 may be 30% to 35% more transmissible than BA.1,” STAT News reports.

The question scientists hope to answer, then, is why BA.2 has this transmission advantage over BA.1. Do BA.2’s additional mutations lend it some adaptation in how it interacts with human cells, enabling faster spread? Or is BA.2 more capable of evading protection from past infection or vaccination compared to BA.1, leading it to cause more reinfections and breakthrough cases?

While we don’t know the answers to these questions yet, early data are indicating that there’s no major difference in disease severity between BA.1 and BA.2. In other words, BA.2 isn’t more likely to cause severe symptoms.

“There is no evidence that the BA.2 variant causes more disease, but it must be more contagious,” Danish Health Minister Magnus Heunicke said at a news conference last week, Reuters reported.

Why do some articles call BA.2 a “stealth variant?”

You might have seen some headlines referring to BA.2 as a “stealth variant” or a “stealth version of Omicron.” This is because of one major difference between BA.2 and BA.1: while BA.1 can be identified with a PCR test due to a key mutation that’s visible on PCR test results, BA.2 does not have this mutation.

As a result, BA.2 can be more time-consuming for COVID-19 testing labs to identify: labs need to sequence a sample’s genome to identify this strain rather than simply look out for an indicator on a PCR test. It’s unclear how much of a difference this will make in the U.S.’s ability to track BA.2, however, as many labs across the country are already performing routine full-genome sequencing of coronavirus samples.

How well do vaccines work against BA.2?

So far, it seems like there is no significant difference in vaccine protection between BA.1 and BA.2, at least when it comes to severe symptoms—which makes sense, scientists say, given how well vaccines have worked against every major variant to emerge thus far.

Early findings in this area come from the U.K., which designated BA.2 as a “Variant Under Investigation” (separate from BA.1) about a week and a half ago. This past Friday, the U.K.’s Health Security Agency released a report with information on BA.2, including how it compares to BA.1 or original Omicron.

Overall, U.K. epidemiologist Meaghan Kall wrote in a Twitter thread summarizing the report, early evidence suggests that “BA.2 is no more immune evasive than Omicron,” though confidence in this statement is low. The report found that, for Brits who had received booster shots, vaccine effectiveness against symptomatic COVID-19 disease was 70% for BA.2 and 63% for BA.1. The confidence intervals on these effectiveness estimates overlapped, indicating that vaccines perform similarly against BA.2 and BA.1.

When it comes to disease severity, Kall wrote, the U.K. doesn’t have enough data to compare BA.2 and BA.1; early data on this topic (suggesting BA.2 is not more severe) have come from Denmark and India.

How will BA.2 impact the U.S.’s COVID-19 trajectory?

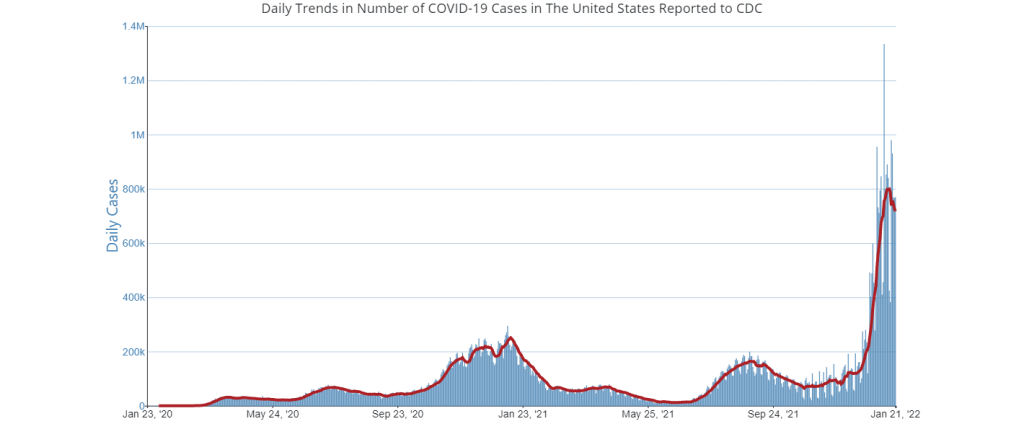

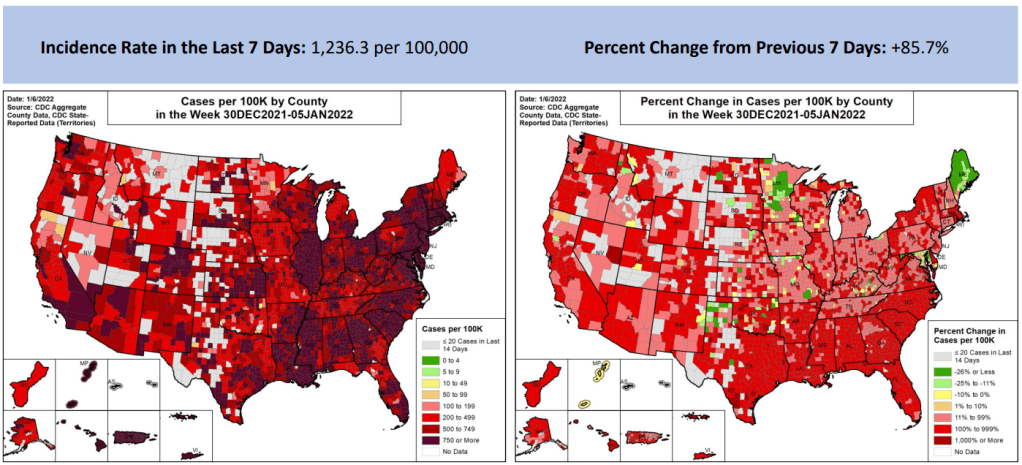

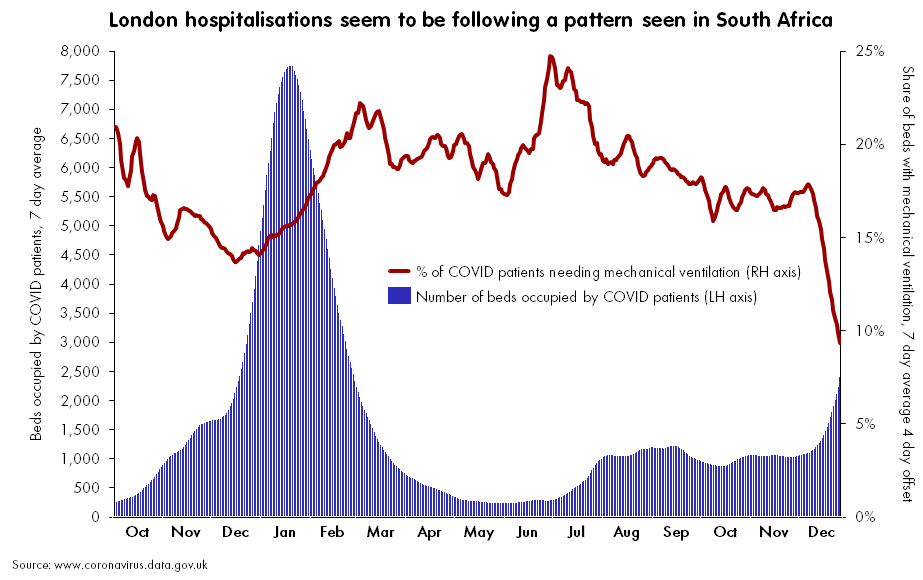

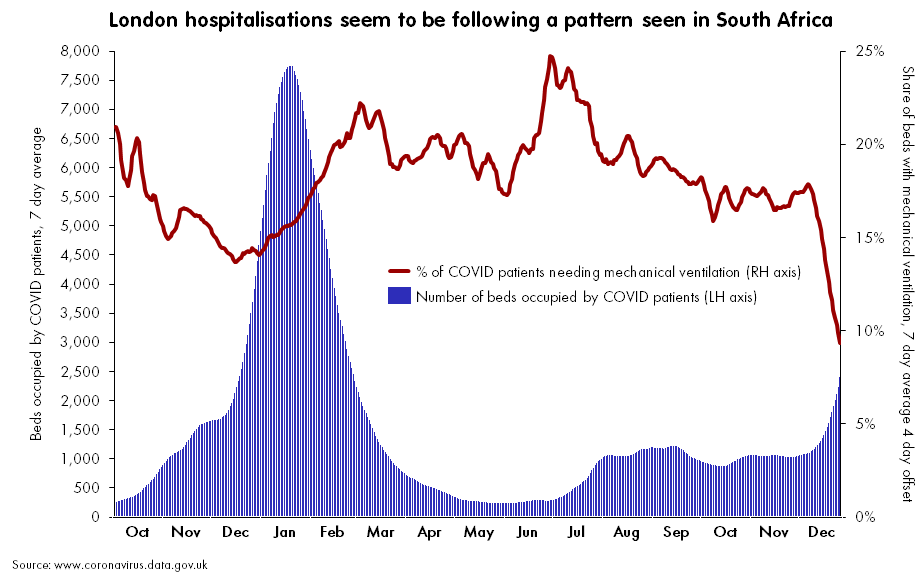

BA.2 has already outcompeted BA.1 in some parts of Europe and Asia, and epidemiologists expect that countries like the U.K. and the U.S. could also follow this pattern—though it will likely be a longer, slower replacement process compared to the intense way Omicron pushed out Delta. A bigger unknown here is what effect this strain may have on case numbers, hospitalizations, and deaths.

Countries and regions now passing the peaks of their Omicron BA.1 waves have extremely high levels of population immunity. As a result, people who are fully vaccinated with boosters and/or recently infected with Omicron BA.1 likely will have a lot of immune system protection against BA.2, though we don’t yet have good data on exactly how robust this protection is.

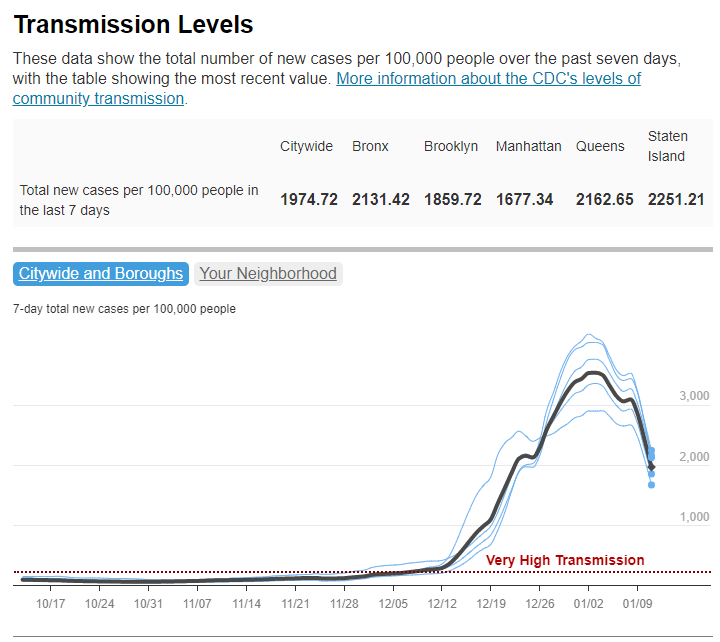

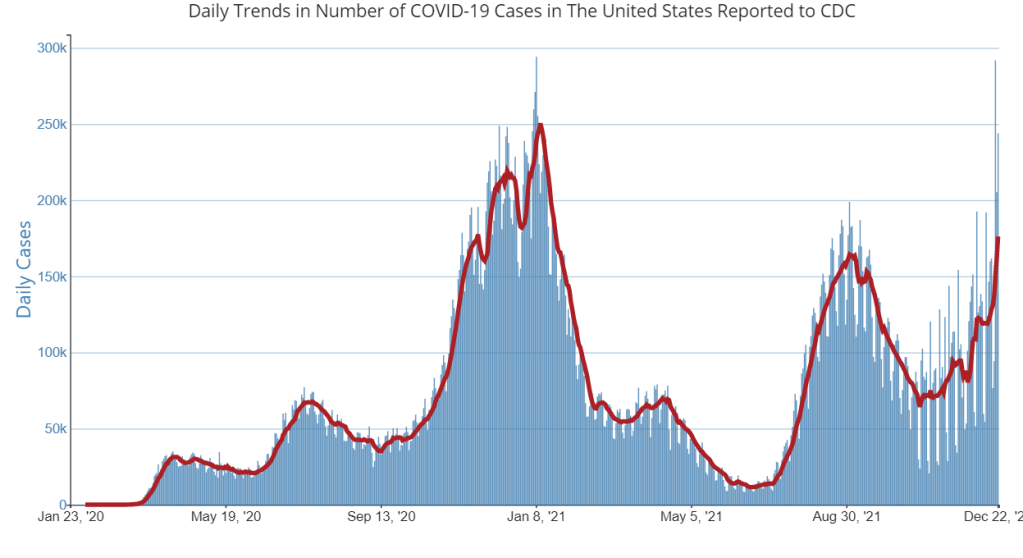

So, could BA.2 cause the current downturn in U.S. COVID-19 cases to reverse? It’s possible, explains Andrew Joseph in a recent STAT News article. However, thanks to our high immunity levels, a further spike in cases could be “broadly limited to infections” rather than causing major increases in hospitalizations and deaths. In the coming weeks, we’ll get a better sense of how well prior Omicron infections protect against BA.2 and other key information that will inform our understanding of how this strain may change the country’s COVID-19 trajectory.

Right now, COVID-19 experts are closely monitoring BA.2, but they’re not hugely concerned. As Dr. Jetelina put it in a recent Your Local Epidemiologist post, the bigger worry right now is that another variant could “pop out of nowhere” like Omicron did in November.